Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Chemistry, Medicinal

Targeting EGFR with small-molecule inhibitors is a valid strategy in cancer therapy. Since the approval of the first EGFR-TKI in 2003, a huge number of EGFR inhibitors were reported. Classification of these inhibitors could help the researchers to understand their structure-activity relationship. Herein, we introduce different types of classifications of the EGFR-TKIs, which received global approval for clinical use. In the following, the EGFR-targeting drugs are classified based on their chemistry, clinical use, target kinases, and the type of inhibition/interaction with EGFR.

- kinase inhibitor

- EGFR

- classification of EGFR-TKIs

- chemical classification

- Pharmacological classification

- target kinase-based classification

- Type of inhibition/interaction-based classification

1. Chemical Classification

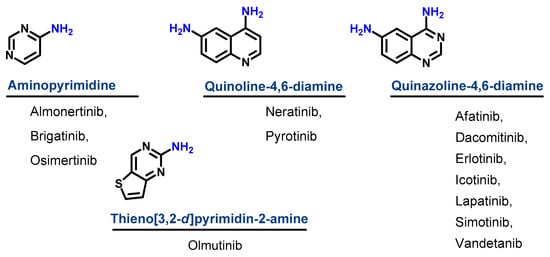

Based on their chemical structures, the approved EGFR-TKIs can be classified into three subclasses. The first subclass is the aminopyrimidine derivatives which include almonertinib, brigatinib, and osimertinib. In this study, olmutinib is considered as a fused aminopyrimidine derivative. The second group has a quinoline-4,6-diamine nucleus and includes two derivatives, neratinib and pyrotinib. The third group is the quinazoline-4,6-diamine-based derivatives which include afatinib, dacomitinib, erlotinib, icotinib, lapatinib, simotinib, and vandetanib, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Chemical classification of EGFR-TKIs.

2. Classification Based on the Types of Interaction with EGFR

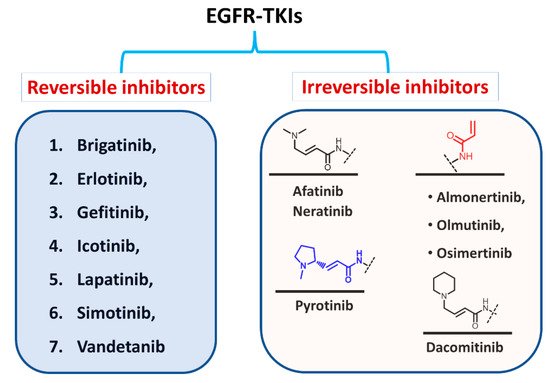

Based on the type of inhibition of the EGFR activity, the approved EGFR-TKIs can also be classified as reversible and irreversible inhibitors, as shown in Figure 5. For the first type, the inhibitors competitively bind to the ATP binding site in the EGFR through noncovalent interactions involving electrostatic, hydrogen-bonding, and hydrophobic interactions [24].

Figure 5. Classification of EGFR-TKIs based on the nature of inhibition of EGFR.

In the second type, the EGFR inhibitors form a covalent bond with the cysteine residue in the EGFR. The structure of these inhibitors is characterized by the presence of an electrophilic side chain that acts as a Michael acceptor which chemically reacts with the cysteine thiol group to form a covalent adduct [25].

3. Classification Based on the Clinical Use

The EGFR inhibitors can also be classified into three groups based on the types of cancers for which they were approved [26]. The first group includes drugs that were approved for the treatment of NSCLC such as afatinib, almonertinib, brigatinib, dacomitinib, erlotinib, gefitinib, icotinib, olmutinib, and osimertinib. The second type includes drugs approved for the treatment of breast cancer such as lapatinib and neratinib, and pyrotinib. On the other hand, the third group includes drugs approved for other types of cancers such as thyroid cancer (vandetanib), pancreatic cancer (erlotinib), and solid cancers (simotinib).

4. Classification Based on the Target Kinases

The approved EGFR-TKIs may also be classified according to their target kinases into (1) selective EGFR inhibitors which target EGFR with high selectivity such as gefitinib; (2) dual EGFR inhibitors such as lapatinib which can target EGFR and ErbB-2; and (3) multi-kinase inhibitors such as brigatinib, pyrotinib, and vandetanib. These drugs have broad-spectrum activity against multiple kinases other than the EGFR [27].

5. Classification into the First, Second, and Third Generation

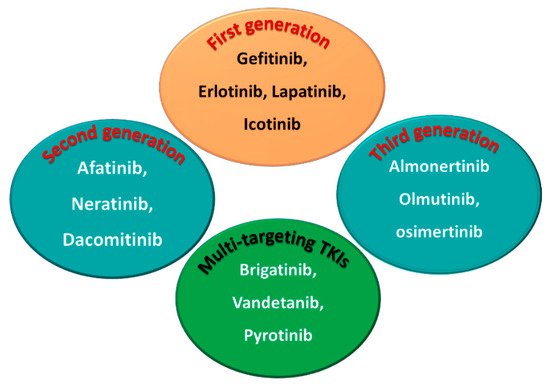

Among the approved EGFR-TKIs, gefitinib, erlotinib, lapatinib, and icotinib are classified as first-generation EGFR inhibitors, as shown in Figure 6. The drugs in this class bind reversibly to the PTK domain of the EGFR, which leads to the inhibition of the binding of ATP to the EGFR and consequently to the inhibition of EGFR activation and cellular proliferation [28]. The chemical structures of the four drugs consist of a basic quinazoline nucleus attached to a substituted aniline moiety, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 6. First-, second-, and third-generation EGFR-TKIs and the multi-targeting inhibitors.

On the other hand, afatinib, neratinib, and dacomitinib are classified as second-generation EGFR-TKIs. These three drugs contain a Michael acceptor site which allows them to bind covalently to the EGFR, leading to the irreversible inhibition of the kinase activity, which provides an advantage over first-generation EGFR-TKIs [29]. The chemical structures of these drugs consist of quinazoline or a quinoline nucleus which bears a crotonamide side chain (Michael acceptor site) substituted at the terminal carbon by a tert-amino group.

The third-generation EGFR inhibitors include almonertinib, olmutinib, and osimertinib [30]. The chemical structures of these drugs include a pyrimidine nucleus attached to a substituted anilino or phenoxy moiety. These moieties bear an acrylamide group that, as noted above, can form a covalent bond with the cysteine residue in the EGFR.

On the other hand, brigatinib, vandetanib, and pyrotinib are classified as multi-kinase inhibitors due to their inhibitory activities against kinases other than the EGFR [31].

The emergence of EGFR T790M and C797S mutation has led to the rapid development of resistance to the first- second- and third-generation EGFR-TKIs [30]. The C797S mutation also deprives the irreversible inhibitors of the EGFR of the ability to bind covalently to the kinase. In addition, the emergence of EGFR double and triple (del19/L858R + C797S ± T790M) mutations challenges the therapeutic effectiveness of EGFR-TKIs. These problems underscore the ongoing need to develop new and potent EGFR-TKIs.

Recently, several fourth-generation allosteric EGFR inhibitors that bind to a site in the EGFR other than the PTK domain were reported [32]. However, although these inhibitors are ineffective against NSCLC with a mutated EGFR, they display synergistic anticancer effects when combined with an EGFR inhibitor such as osimertinib or the monoclonal antibody, cetuximab.

Currently, several fourth-generation EGFR-TKIs are being evaluated in regard to their efficacy against cancers carrying double or triple EGFR mutations [33,34,35]. One of these compounds, BBT-176, is in Phase I/II trials in NSCLC patients with advanced lung cancer [35], but these inhibitors are not yet approved for clinical use.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules26216677

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!