Universal neonatal screening is the most useful procedure for early detection of congenital deafness. Neonatal hearing screening facilitates a confirmed diagnosis of neonatal deafness in the first 4 months of life while without this practice the diagnosis is usually delayed up to 35 m. In the same way, the treatment of children diagnosed from neonatal screening begins before 7 m, and in its absence, it is delayed on average up to 35 m.

- neonatal hearing screening

- deafness

- newborn screening

1. Introduction

Congenital deafness is a major pediatric problem, affecting about 1–3 per 1000 newborns [1]. Without adequate treatment, its most feared consequence is deaf-muteness. From the mid-Renaissance [2][3][4] to the end of the 20th century, most deaf children achieved social communication through sign language ( Figure 1 ).

The early treatment of these children through auditory rehabilitation programs for learning sound processing and cochlear implantation has been a historic milestone. This fact supports the need for the diagnosis of congenital deafness to be universal and, as soon as possible, that is, through neonatal screening. In this line, it is worth remembering that more than 90% of deaf newborns have healthy parents and that many of profoundly deaf require a cochlear implant [5][6].

Neonatal hearing screening has been successfully implemented in most Western countries. Its set-up has been slow due to the multiple difficulties that its universal application entails. The organization at a regional level is complex and the technical equipment, preparation of health personnel and administration in general makes it a hard and costly enterprise to run. It involves several care services and levels of health staff; it should be universal, and it should be carried out mainly in the short postpartum stay in maternity ward. A good performance is needed to avoid the overload of hospital services concerned. There is currently a strong discussion about the more appropriate technical equipment and protocols to be used, but all the programs manage to increase the early detection of congenital deafness in the neonatal period, which has made it possible to reduce the age of treatment and have better clinical prognosis and psychosocial adaptation [7][8][9][10].

We have systematically applied this practice at the Hospital Clínico in Valencia (Spain) during the last 30 years [11][12][13].

2. Neonatal Hearing Screening

Much time and effort has been devoted to finding the most efficient and accurate procedures, protocols, and equipment for screening, diagnosing, and treating children who are deaf or hard of hearing [14].

Universal neonatal screening is the most useful procedure for early detection of congenital deafness. Neonatal hearing screening facilitates a confirmed diagnosis of neonatal deafness in the first 4 months of life while without this practice the diagnosis is usually delayed up to 35 m. In the same way, the treatment of children diagnosed from neonatal screening begins before 7 m, and in its absence, it is delayed on average up to 35 m [15][16].

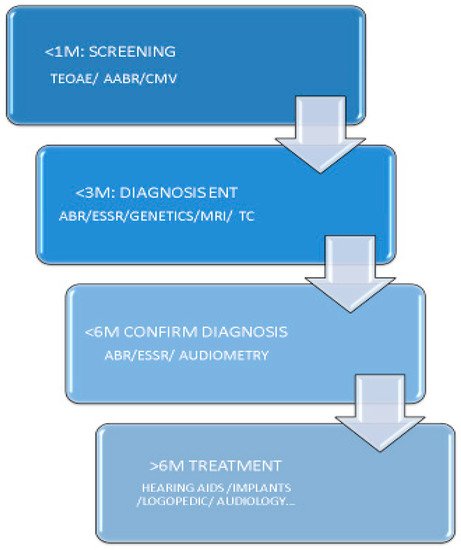

Under normal conditions if the technical application is adequate, the referral of patients to otorhinolaryngology (ENT) service will be less than 4%. Diagnostic confirmation must be conducted in good conditions before 3 m and audiologic study before 5–6 m in order to begin treatment at approximately 6 m ( Figure 2 ) [7][17].

At the present there is controversy about the technical equipment and protocols to be used, but all the programs reduce the age of treatment achieving a better prognosis for hearing and psychosocial adaptation [7][8][9][10].

3. Types of Neonatal Hearing Screening

It should be emphasized that screening does not seek a firm diagnosis of the disorder but rather the identification of suspected newborns in order to focus the subsequent effort to its diagnostic confirmation.

Given that TEOAE do not allow the identification of neural deafness, most authors advise the use of AABR in all children with auditory risk factors due to neural or syndromic pathology [7][8][9][10][17].

Currently, more than half of the countries with neonatal hearing screening use TEOAE thanks to its low cost as well as its easy and fast technical implementation, although more programs are increasingly using a mixed protocol (TEOAE-AABR) or, less frequently, only AABR [1][8][9][18][19].

Concerning the place to carry out the first audiological examination, two alternatives are observed according to local availability of resources, one that conducts the examination at the maternity ward before discharge (assuming more false positives but less losses) and another that prefers to perform the test later in external office (with less false positives and more losses). The former is better performed by all nurses and the latter is better conducted in an external office by dedicated staff that filters the referral to ENT. This is recommended also for all retests in babies that fail the first test [20].

4. Some Details of Practical Interest in Hospital Hearing Screening

1. The test should be performed on all newborns in a quiet room by trained health personnel that also will fill the database with the results.

2. Although the study can be carried out by doctors or nurses, either from the pediatric as well as from the otolaryngology or obstetrics services, due to their location and numerical availability, nurses from obstetrics are the most suitable professionals. If possible, it is better that all obstetric nurses are trained in hearing screening because it permits to do the test in all shifts, all day long and covering holidays. Nevertheless, in large hospitals one can dedicate a special team of five health personnel to do it (it improves reliability but worsens continuity because of holidays and leaves).

3. It is advisable to have two devices available in order not to stop testing if one malfunctions. For the same reason, two or three probes, ear tips and cables must be ready.

4. Do not spend more than 5 min on a test. If it is impossible to carry out due to the child’s restlessness or other causes, it must be stopped and repeated later. Try to do it after feeding, in a quieter place or using breastfeeding or a pacifier.

5. Do not insist on testing, if a test is a “fail” two times, refer to next level after assuring that the ear tip and probe fit, were right and there were no technical problems (too much noise, etc.) [7]. On AABR, check electrical noise and disconnect as much electronic devices as you can (including mobile phones telephones, pulsioximeters, lights, etc.) and prepare well the skin before in order to diminish the impedances (you can use a special gel).

6. In cases where it is required to repeat the test for failing to pass the first test/step it is important to discuss the inpatient versus outpatient retest issue because the former has more failures (because of middle ear status) but a lower lost to follow-ups; the later has opposing figures. The second test/step must be performed by an expert health personnel before 2–3 weeks of age (in order to do a cytomegalovirus test if it fails), it must be bilateral, not testing just the ear that fail before and controlling the time you are spending, if it fails a pair of tries just send it to ENT (Joint Committee on Infant Hearing recommend just one try in good conditions) [7].

7. Parents should be informed as soon as possible of the test results. It is very important to explain what results of the screening test mean: the pass means a normal auditory function but refer means only that technique cannot, at that moment, detect a normal function and that can be also for technical reasons or lack of aeration of middle ear, so another test must be performed in order to confirm the diagnosis some days later. This avoids the excess of anxiety in the family. It is basic to choose the best moment when to communicate results and explain clearly what the screening tests really mean showing the differences of screening versus diagnosis. On the other hand, it is important to remark also the possibility of a late onset hearing loss in spite of a normal screening test. Finally, it is necessary to give all information of this issue in a proper culturally competent way offering an appropriate support [21].

In addition, high risk neonates are controlled in our external office and ENT services in order to detect late onset hearing loss till they have at least two years and usually after that age [17].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/healthcare9111436

References

- Wroblewska-Seniuk, K.E.; Dabrowski, P.; Szyfter, W.; Mazela, J. Universal newborn hearing screening: Methods and results, obstacles, and benefits. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 81, 415–442.

- de Yebra, M. Libro llamado Refugium Infirmorum, muy útil y Provechoso para Todo Genero de Gente, en el Qual se Contienen Muchos Avisos Espirituales para Socorro de los Afligidos Enfermos, y para Ayudar a bien Morir a los que Están en lo Ultimo de su vida; con un Alfabeto de S. Buenaventura para hablar por la mano; Luys Sanchez: Madrid, Spain, 1593.

- Oviedo, A. El libro “Refugium Infirmorum” (Madrid, 1593), del Monje Franciscano Fray Melchor de Yebra; Clásicos Cultura Sorda: Berlin, Germany, 2007.

- Bonet, J.P. Reduction de las Letras y arte para Enseñar a Ablar a los Mudos; ; Francisco Abarca de Angulo: Madrid, Spain, 1620; pp. 126–127.

- National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management. Home Page. 2021. Available online: http://www.infanthearing.org/ (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- White, K.R. The Evolution of EHDI: From Concept to Standard of Care. NCHAM ebook, 2021 eds. Available online: http://www.infanthearing.org/ehdi-ebook/2021_ebook/1b%20Chapter1EvolutionEHDI2021.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2021).

- Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. J. Early Hear. Detect. Interv. JEHDI 2019, 4, 1–44.

- Bussé, A.M.L.; Mackey, A.R.; Hoeve, H.L.J.; Goedegebure, A.; Carr, G.; Uhlén, I.M.; Simonsz, H.J.; EUS€REEN Foundation. Assessment of hearing screening programmes across 47 countries or regions I: Provision of newborn hearing screening. Int. J. Audiol. 2021, 10, 1–10.

- Mackey, A.R.; Bussé, A.M.L.; Hoeve, H.L.J.; Goedegebure, A.; Carr, G.; Simonsz, H.J.; Uhlén, I.M.; Foundation, F.T.E. Assessment of hearing screening programmes across 47 countries or regions II: Coverage, referral, follow-up and detection rates from newborn hearing screening. Int. J. Audiol. 2021, 9, 1–10.

- Bussé, A.M.L.; Mackey, A.R.; Carr, G.; Hoeve, H.L.J.; Uhlén, I.M.; Goedegebure, A.; Simonsz, H.J.; EUS€REEN Foundation. Assessment of hearing screening programmes across 47 countries or regions III: Provision of childhood hearing screening after the newborn period. Int. J. Audiol. 2021, 9, 1–8.

- Sequí, J.M.; Mir, B.; Paredes, C.; Brines, J.; Marco, J. Resultados preliminares en la aplicación de las otoemisiones acústicas provocadas en el periodo neonatal. An. Esp. Pediatr. 1992, 33, 73–75.

- Sequí, J.M.; Mir, B.; Paredes, C.; Brines, J.; Marco, J. Resultados de un estudio sobre la presencia de otoemisiones espontáneas en el recién nacido. An. Esp. Pediatr. 1992, 37, 121–125.

- Sequí, J.M.; Brines, J.; Mir, B.; Paredes, C.; Marco, J. Estudio comparativo entre otoemisiones provocadas y potenciales auditivos tronculares en el periodo neonatal. An. Esp. Pediatr. 1992, 37, 457–460.

- White, K.R. Newborn hearing screening. In Handbook of Clinical Audiology, 7th ed.; Katz, J., Medwetsky, L., Burkard, R., Hood, L., Eds.; Lippincott, Williams, & Wilkins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2014.

- Schildroth, A.N.; Karchmer, M.A. Deaf Children in America; College Hill Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1986.

- Yoshinaga-Itano, C.; Sedey, A.L.; Coulter, D.K.; Mehl, A.L. Language of early- and later-identified children with hearing loss. Pediatrics 1998, 102, 1161–1171.

- Trinidad-Ramos, G.; de Aguilar, V.A.; Jaudenes-Casaubón, C.; Núñez-Batalla, F.; Sequí-Canet, J.M. Comisión para la Detección Precoz de la Hipoacusia (CODEPEH). Early hearing detection and intervention: 2010 CODEPEH recommendation. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Esp. 2010, 61, 69–77.

- Neumann KEuler HA Chadha, S.; White, K.R. A Survey on the Global Status of Newborn and Infant Hearing Screening. J. Early Hear. Detect. Interv. 2020, 5, 63–84.

- Pacheco, M.D.C.M.; Canet, J.M.S.; Tobele, M.D. Programas de detección precoz de la hipoacusia infantil en España: Estado de la cuestión. Acta Otorrinolaringol. Española 2021, 72, 37–50.

- Sequí Canet, J.M.; Collar del Castillo, J.; Lorente Mayor, L.; Oller Prieto, A.; Morant Barber, M.; Peñalver Giner, O.; Valdivieso Martínez, R. Hearing screening based on otoacoustic emissions in infants born in secondary-level hospitals: Feasible, efficient and effective. Acta Pediatr. Esp. 2005, 63, 465–470.

- Núñez-Batalla, F.; Jáudenes-Casaubón, C.; Sequí-Canet, J.M.; Vivanco-Allende, A.; Zubicaray-Ugarteche, J. Recomendaciones CODEPEH 2014 para la detección precoz de la hipoacusia diferida. An. Pediatría 2016, 85, 215.e1–215.e6.