4.2. Culture, Growth, and Phenotypes

C. auris is able to grow after 24 h of culture at 37 °C on Sabouraud agar, where it develops opaque white to creamy colonies. Chromogenic media have recently become popular for

C. auris culture and identification. In the medium CHROMagar Candida

®, colonies present with pink to pale purple tonalities. However, differences in the tone of the colonies have been reported, dependent on the country of origin and clade. Some authors have, hence, proposed these chromogenic media complemented with Pal agar (with extract of sunflower seeds) for presumptive identification of

C. auris [

56].

Although it is not able to grow in media with cycloheximide,

C. auris presents a marked thermotolerance and salt tolerance, growing in a temperature range from 37–42 °C, unlike other

Candida or fungal species [

15,

20,

41,

43,

49,

57,

58,

59,

60]. These particular traits, beyond modified chromogenic media, can also be used for its presumptive identification in microbiology laboratories with technical limitations or before definite molecular identification.

C. auris assimilates and weakly ferments glucose, saccharose, and trehalose; and assimilates raffinose, melezitose, soluble starch, and ribitol or adonitol. However, it is not capable of fermenting galactose, maltose, lactose, or raffinose [

6]. This glycidic fermentation and assimilation profile also makes it possible to generate sensitive and specific culture media based on mannitol, dextrose, and dulcitol to isolate and presumptively identify

C. auris in clinical practice [

15].

Microscopically,

C. auris is a yeast with 2–3 × 2.5–5 μm ovoid cells similar to

C. glabrata [

43]. It presents two important clearly distinguishable phenotypes with different behaviour and virulence [

43,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69]:

-

Non-aggregative phenotype: yeast cells arrange as isolated or, sometimes, coupled cells, similarly to other Candida species.

-

Aggregative phenotype: some isolates keep daughter cells attached after budding, creating large aggregates that cannot be separated by physical disruption after vigorous vortexing for several minutes.

The different characteristics in behaviour, virulence, and pathogenicity determinants of both phenotypes will be posteriorly discussed.

Unlike other species of the genus

Candida, such as

C. albicans, considered the most virulent species of the group, and with high filamentation capacity [

70,

71,

72],

C. auris is not considered able to develop true hyphae, chlamydospores, or germ tubes [

34,

36,

58,

73,

74]. The formation of very rudimentary pseudohyphae had only been described occasionally [

43,

62]. However, more recent studies have reported filamentation in some strains of

C. auris under certain environmental conditions or stress [

61,

71,

75,

76]. Yue et al. described an in vivo inheritable phenotypic change or switch towards a filamentous or filamentation-competent phenotype, induced by passage through the mammalian organism, different salt concentrations of NaCl between 10% and 26%, and thermal changes [

75]. Our group recently described filamentation in non-aggregative and aggregative strains in an invertebrate model in wax moth larvae at 37 °C [

61]. On the other hand, Bravo-Ruiz et al. were able to induce filamentation in vitro through genotoxic stimulation [

76]. This possibility of pseudohyphae formation has finally been demonstrated in strains from the four main clades, according to the work of Fan et al. [

77].

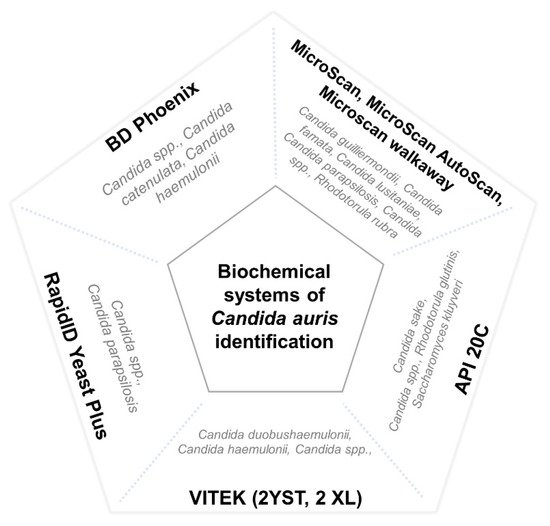

4.3. Difficulties in C. auris Identification

There are numerous methods used for the identification of

Candida species in clinical microbiology laboratories. Nevertheless, most of them use commercial systems of biochemical characterization, which are unable to properly identify

C. auris. These methods usually misidentify it as

C. haemulonii,

Rhodotorula glutinis,

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, or, less frequently, as other Candida species such as

C. famata,

C. dobushaemulonii,

C. sake,

C. lusitaniae,

C. albicans,

C. guilliermondii, or

C. parapsilosis [

17,

18,

43,

52,

57,

58,

73,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83]. However, erroneous identification has been reported with more complex diagnostic methods, such as filmarray systems [

84] and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) [

85]. The main misidentified species of different commercial biochemical systems is represented in

Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main misidentified species of different commercial biochemical systems. Misidentification of C. auris by means of the VITEK systems has specially been reported with isolates of the east Asian and African clades.

In primary or secondary hospitals with fewer resources, as well as in developing countries with limited access to sophisticated and expensive methods such as MALDI-TOF or molecular techniques, such identification sometimes arrives at

Candida spp. without reaching the species level in non-invasive samples [

19,

86]. However, due to its relevance for public health, accurate and rapid diagnostic methods are needed to facilitate prompt diagnosis, effective patient management, and control of nosocomial outbreaks.

At present, the new MALDI-TOF systems, after including the specific spectra in the databases [

87,

88,

89], are able to provide specific diagnoses at species level. In developing countries with limited access, this method could be replaced by DNA detection techniques such as PCR [

89]. Despite the sequencing of genetic loci (

RPB1,

RPB2,

D1/D2) and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) being commonly used, especially in reference centres [

58,

74,

90], different PCR endpoint trials, multiplex PCR [

91], or PCR of Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphisms (RFLP) [

89,

92] could be more accessible in centres with economic or equipment limitations. Recently, two commercially available PCR assays, AurisID (OLM, Newcastle Upon Tyne, UK) and Fungiplex Candida Auris RUO Real-Time PCR (Bruker, Bremen, Germany) have been shown to reliably identify

C. auris, even at low DNA concentrations [

93].

In addition, many microbiology laboratories presumptively identify

C. auris using chromogenic media, due to better accessibility and lower cost. Consequently, some media which allow for rapid screening after 24 h of incubation have been created, such as HiCrome

C. auris [

94]. Furthermore, the culture medium CHROMagar

Candida, complemented with Pal agar [

56], has been shown to be useful in the differentiation of

C. auris from

C. haemulonii. Due to its triazole resistance, the use of high concentration fluconazole as media supplementation could optimise the presumptive recognition of

C. auris in higher prevalence zones which lack easy access to definitive identification techniques [

95].

4.4. Virulence

Since C. auris became a major public health problem, efforts have been devoted to investigating the pathogenicity degree of several clones, strains, and worldwide isolates of C. auris. Nevertheless, data on its virulence compared to other Candida species, as well as on its phenotypical, morphological, or molecular pathogenicity determinants, are still limited.

C. albicans is considered the most virulent species of the

Candida genus [

70,

71,

96].

Candida species express several pathogenicity factors that contribute to their pathogenicity and virulence within the host. Among them, it is important to highlight the synthesis of molecules such as phospholipases, aspartic-proteases, or molecules related to the recognition of host proteins that increase tissue adhesins, and morphogenesis, as well as a phenotypic switch to a filamentous phenotype, enabling higher adaptability to intrahost changes [

96].

Despite

C. auris initially being considered unable to filament in vivo or, in any case, only able to produce rudimentary pseudohyphae under stress [

75,

76], some works using strains from different origins and clones have described an in vivo virulence similar or even greater than that of

C. albicans [

43,

62,

97]. Nonetheless, the results of the few studies on the pathogenicity of

C. auris are relatively diverse, as seen in

Table 1 [

43,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

97]. Differences have been noted, not only in comparison with other species of the genus, but also regarding different clones, strains, and individual isolates. Further studies are, hence, needed, using a larger number of strains from different geographical regions, clinical isolates, and clades [

50,

61,

65,

98].

Table 1. Virulence of C. auris in different experimental animal models.

| Organism |

Virulence Results |

Reference |

| C. elegans |

C. hameulonii < C. auris = C. albicans |

[99] |

| C. elegans |

Non-Ag C. auris > Ag-C. auris |

[67] |

| D. rerio |

C. auris > C. albicans > C. haemulonii |

[97] |

| D. melanogaster |

C. auris > C. albicans

Non-Ag C. auris = Ag C. auris > C. albicans |

[100] |

| G. mellonella |

C. albicans > C. auris > C. parapsilosis

Non-Ag C. auris > Ag-C. auris

Non-invasive isolates = invasive isolates |

[61] |

| G. mellonella |

C. auris ≥ C. albicans

Non-Ag C. auris > Ag-C. auris |

[43] |

| G. mellonella |

Non-Ag C. auris ≥ C. albicans and C. glabrata

Ag-C. auris = C. glabrata |

[62] |

| G. mellonella |

C. auris < C. albicans

Non-ag C. auris = Ag C. auris |

[66] |

| G. mellonella |

C. auris < C. albicans

Non-ag C. auris = Ag C. auris |

[63] |

| G. mellonella |

C. albicans > C. auris > C. haemulonii |

[64] |

| G. mellonella |

Non-Ag C. auris > Ag-C. auris

Blood isolates > respiratory and urine isolates |

[67] |

| Neutropenic Mus musculus |

C. auris = C. haemulonii |

[64] |

During the last several years, several research groups have analysed the pathogenicity differences of

C. auris in comparison to other

Candida species. Different models have been used: from in vitro studies assessing different transcriptional profiles from strains with different phenotypes [

101], to animal models with a diverse complexity. These include invertebrate models in

Caenorrhabditis elegans [

67,

99],

Drosophila melanogaster [

100], and the recently popularised model in wax moth larvae,

Galleria mellonella [

43,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67], as well as vertebrates such as the traditional murine model [

64], and, more recently, the zebrafish

Danio rerio [

97].

G. mellonela has recently gained importance in the study of fungal pathogenesis and, especially,

Candida spp. virulence. Owing to the functional and structural similarity of the larval innate immune system to that of mammals, its low cost, as well as the possibility of working with larger samples in short timeframes thanks to its short vital cycle and, importantly, due to the lack of ethical implications involved, its popularity has been increasing recently [

61,

71,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107].

The first data of experimental pathogenicity of

C. auris came from the studies of Borman et al. [

43], using 12 isolates from the United Kingdom outbreak. They showed more aggregative phenotypes of

C. auris to be in vivo than non-aggregative strains. Moreover, the first were considered almost as virulent as

C. albicans, despite their striking inability to filament. In addition, Sherry et al. [

62], who also used four different strains from the United Kingdom, documented that non-aggregative phenotypes of

C. auris showed a higher lethality than

C. albicans reference strain SC5314, using a standardised inoculum of 10

5 colony forming units (CFU), while C. glabrata and aggregative

C. auris were significatively less virulent. In a model of

C. elegans using 37

C. auris strains from Venezuela [

9], they also appeared to show a similar pathogenicity degree to

C. albicans, but less virulence than

C. haemulonii [

99]. However, these results could not be reproduced using strains of other geographical origins.

The works of Carvajal et al. [

66] and Muñoz et al. [

64] analysed the differential pathogenicity using Colombian strains. The study of the first group in

G. mellonella did not show significative differences in the virulence of aggregative and non-aggregative strains, with more than 50% of the strains being less lethal than the reference strain of

C. albicans SC5314; these findings are similar to the results obtained by Romera et al. [

63] with Spanish isolates, also in

G. mellonella. The second group developed both a

G. mellonella and a neutropenic murine model, and used

C. albicans SC5314 and ATCC10231 strains as a high pathogenicity control, and

C. haemulonii as a low virulence control. Despite

C. auris phenotypes not being determined, the four strains used showed a significant intermediate lethality between

C. albicans and

C. haemoulonii in

G. mellonella, as reported by Garcia-Bustos et al. [

61], but these results were not replicated in the murine model.

Therefore, this heterogenicity in intra- and interspecific virulence advocates for the hypothesis that the morphogenetic variability is an inherent trait of

C. auris, and an indicator of its flexibility and adaptability to different environments and stimuli [

61], particularly after some authors induced aggregation after exposition to triazoles and echinocandins [

108].

This potential ability to phenotypically switch may result from a survival mechanism outside of the host. In fact, isolates from environmental and epidemiological surveillance samples more frequently presented an aggregative phenotype. Moreover, they demonstrated a greater ability to form biofilm structures; both traits related to the difficulty for their definitive eradication in the health environment and in colonised patients [

109,

110]. In addition, replicative aging resulting from asymmetric cell division has been shown to cause further phenotypic differences, and older

C. auris cells have been associated with increased virulence in

G. mellonella [

111].

The pathogenicity determinants of

C. auris are not completely clarified. The formation of biofilms and filamentation constitute two of the main virulence factors of

Candida species. Other important factors have been described, such as phenotypic switch, metabolic flexibility and adaptation to different pH, production of extracellular hydrolytic and cytolytic toxins, heat shock proteins (HSP), and development of adherence and recognition mechanisms of surfaces and host cells [

112,

113].

As previously stated,

C. auris is able to filament both in vivo and in vitro [

61,

75,

76,

77]. However, the pathogenic implication of hyphae or pseudohyphae formation in

C. auris is still unknown. Some studies have not been able to demonstrate the expression of proteins related to the formation of these structures, such as the candidalysin (ECE1) or hyphal cell wall protein (HWP1) in certain

C. auris strains [

49]. Yue et al. [

75] analysed the expression profile of genes related to the regulation of filamentation, and discovered similarities with

C. albicans, showing an increased expression of genes implicated in hyphae formation such as

HGC1,

ALS4,

COH1,

FLO8,

PGA31, and

PGA45 in filamentous strains, with regard to strains that only showed yeast-form structures.

C. auris is able to form biofilms, a trait which also constitutes a major challenge in clinical practice. The colonization of surfaces in patients undergoing any type of instrumentalisation increases, on the one hand, the risk of invasive candidiasis and generating new outbreaks, and decreases, on the other hand, the possibility of eradicating patient colonisation. A large number of IFI cases due to

C. auris have been described related to health devices, such as urinary tract infections (UTI) in patients with indwelling catheters, cardiovascular infections, or neurosurgical instrument-related infections [

16,

17,

18,

114,

115]. The

C. auris tendency to form biofilms in human skin as well as in animal skin models with an elevated microbiological burden [

116] has been related to an increased expression of adhesins (

IFF4,

CSA1,

PGA26,

PGA52,

PGA7,

HYR3, and

ALS5) [

117], with differential regulation based on the biofilm maturity [

117,

118]. In addition, biofilms also influence drug resistance by physical means, by hindering drug penetration in the most isolated regions of the dense biofilms [

117,

119], and expressing genes related to biofilm with added efflux pump action or glucan modifier enzyme action [

117,

119,

120].

Some genomic studies have demonstrated that

C. auris shares some of the pathogenicity determinants with other species of

Candida, such as secretion of aspartic-proteases (SAP), lipases, phospholipases, and YPS proteases [

67,

69]. Other virulence factors include the expression of oxidoreductases, transferases, hydrolases [

67], and haemolysins [

121].

Finally, immune evasion has recently been considered an important trait of

C. auris. Beyond phenotypic plasticity, some works have reported the ability of this fungus to evade neutrophil attack and effective phagocytosis both in human and animal models [

116,

122]. This finding is in line with previous clinical works, suggesting that neutropenia is not an important risk factor for invasive candidiasis by

C. auris [

61].