Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Behavioral Sciences

The growth of fraudulent pesticide trade has become a threat to farmers’ health, agrochemical businesses, and agricultural sustainability, as well as to the environment. However, assessment of the levels of farmers’ exposure to fraudulent pesticides in the literature is often limited. This entry conducted a quantitative study of farmers’ recognition and purchasing behaviors with regard to fraudulent pesticides in the Dakhalia governorate of Egypt.

- pesticides

- fraudulent

- farmers

- behavior

- purchase

- rural areas

- sustainable agriculture

1. Introduction

Product fraud is a global issue that is increasing in magnitude and scope and adversely affecting different market sectors [1,2]. Pesticides are among the most popular fraudulent products in the agri-food market [3,4]. Although the term “fraud” has been used in the field of international business for a long time [5], it has become something of a buzzword in recent years in the field of pesticides. The advance of globalization and the development of technologies have given rise to a more widely accepted conceptualization of fraudulent pesticides as deliberately mislabeled regarding their source and/or identity; additionally, they may lack the manufacturer’s name and address, or are not allowed to be used or sold by national authorities [6]. The term “fraudulent pesticide” describes an array of illicit, illegal, and unauthorized imports or those with counterfeit labeling [7]. For the purposes of this paper, we adopted the classification of Fishel [8], who divided fraudulent pesticides into three main categories, namely, fakes, counterfeits, and illegal parallel imports. Fake pesticides are often sold in simple packs without label information or with minimal labeling about their use and precautions. Such products may contain anything from water or talc to diluted and outdated or obsolete stocks, including restricted or banned materials [6]. Counterfeit pesticides may include products with no active ingredient or a modified product content. These products represent sophisticated copies of genuine products, usually with high-quality packaging and labeling [8]. Finally, illegal parallel imports consist of non-authorized products (not yet registered or mostly banned) or registered products from non-registered distributors [9].

Despite various collaborative and multinational efforts, it is apparent that the problem of fraudulent pesticides is growing. As mentioned in the 2020 status report of the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO) [10], the sales of legitimate pesticides decreased by an average of 4.2% across the EU due to the presence of counterfeits. This equates to a loss of direct sales of EUR 0.5 billion per year. Adding on its knock-on effects in other sectors, the total loss of sales was estimated to be EUR 1.0 billion. The total employment loss as a result of counterfeit pesticides in this sector across the EU was 3584 jobs annually. In terms of the total yearly government revenue, the total loss was estimated to be EUR 0.1 billion in taxes and social security contributions. In the case of Egypt, a report of the Ministry of Agriculture and Land Reclamation (MALR) showed that counterfeit and illegal pesticides accounted for 15% of the market share of pesticides and agrochemicals in 2019 [11]. In terms of the percentage of counterfeits inspected among other sectors in 2019, this report showed that pesticides ranked fourth after clothing, cosmetics and personal care, and pharmaceuticals. The results included in this report are based on a collaboration between regulatory bodies in the governorates and the MALR in implementing inspection campaigns. The objectives of the campaigns respond to the widespread concern for fraudulent pesticides among farmers by monitoring the outlets of manufacture and the sale of pesticides; monitoring any violations that pose a threat to public health, the environment, agricultural production, and agricultural exports; and taking all necessary measures against violators. The main activities implemented during campaigns include comparing the sales of fraudulent pesticides to those authorized by the MALR based on barcode scanning, in addition to lab testing by taking a random sample of pesticides to ensure their quality.

Farmers play an essential role in combating fraudulent pesticides. This role can be achieved by influencing farmers’ behavior regarding the purchase of fraudulent pesticides [12]. Some farmers buy fraudulent pesticides knowingly and intentionally (non-deceptive behavior) or this behavior may be deceptive, when a farmer believes that the package is genuine and he/she is not aware of buying unregistered or illegal products [13]. However, both categories of farmers’ purchasing behavior regarding fraudulent pesticides are affected by numerous factors. The intention to purchase can be viewed as a link between attitudes and purchasing behavior [14,15]. According to Haggblade et al. [16], attitudes toward the efficiency and quality of counterfeit pesticides influence the farmers’ purchase intentions. Positive attitudes toward purchasing genuine pesticides are expected to increase farmers’ likelihood of purchasing these pesticides [17]. The farmer–price relationship should also be taken into consideration. Price is a major factor in the buying decision, and it also influences the choice of product, store, and brand [18,19,20]. Compared to original pesticides, the low price of fraudulent pesticides may encourage farmers, particularly small-scale farmers, to purchase them [12,21]. Moreover, the perception of risks associated with fraudulent pesticides is also one of the main determinants for farmers in forming a subjective judgment of whether to purchase a particular counterfeit [12]. Farmers should be aware of the adverse consequences of fraudulent pesticides in terms of their crop yield and quality of products [17]. Apart from agricultural risks, the use of counterfeit and illegal pesticides also has health consequences. Such pesticides can negatively affect farmers’ health through exposure during application and pose severe health risks to consumers’ health due to the residues of unknown and untested substances in foods [22,23]. Furthermore, many active substances and other constituents used in fraudulent pesticides contain highly toxic impurities, which can pose a risk to soil quality, water, and the health of biodiversity [6,24]. Besides this, there are an increasing number of cases of fraudulent pesticides making negative impacts on the plant protection industry (damage to one’s reputation, a loss of sales, patent and trademark infringement, and the undermining of industry stewardship activities) [7,25,26] and causing economic damage to governments (job losses, lost taxes and levies from the sale of brands, stifling innovation and competitiveness, and inability to effectively regulate the agro-chemical market) [7,26,27]. Finally, the demographic characteristics of farmers could also be important determinants of their purchasing behavior with regard to fraudulent pesticides [12,28,29,30,31]. Practically speaking, even if all of these factors positively motivate farmers not to purchase fraudulent pesticides, recognizing such pesticides is still a dilemma [1,32].

In fact, farmers might not be able to differentiate between fake and original pesticides due to their availability through legitimate distributors or because of the sophistication of pirate copies [33]. To deter and mitigate the negative impacts from the use of fraudulent pesticides, applying effective formal and informal social control mechanisms in the regulatory, production, and supply chain networks is crucial [34,35]. However, combating this issue not only requires the promotion of the farmers’ capacity building in terms of identifying frauds, but also collective action from all stakeholders in the pesticide supply chain [16].

Despite the fact that several studies have been undertaken to measure the quality of fraudulent pesticides by conducting laboratory tests [16,21,24,37,38,39], empirical studies assessing farmers’ exposure to fraudulent pesticides and the factors influencing their purchasing behavior have not received enough attention, especially in the context of Egypt. These factors, including the farmers’ socio-demographic variables, their perception level of risks associated with fraudulent pesticides, and their recognition level of fraudulent pesticides. Therefore, the current study aimed to (i) explore farmers’ risk perception regarding fraudulent pesticides, (ii) identify farmers’ exposure to fraudulent pesticides, (iii) identify the level of recognition of fraudulent pesticides among farmers, and (iv) determine the factors influencing the farmers’ purchasing behavior.

2. Do Farmers’ Recognition and Purchasing Behaviors Matter?

Combating the production and distribution of fraudulent pesticides is a continuous concern for all actors of the pesticide supply chain in order to reduce their adverse impacts on the industry, farmers, and the environment. The present study assessed the current level of farmers’ perceptions, purchasing, and recognition regarding fraudulent pesticides. Furthermore, this study assessed how farmers with behavioral heterogeneity and different socioeconomic characteristics purchase fraudulent pesticides in the study area. The insights into farmers’ behaviors regarding fraudulent pesticides from this assessment enrich existing literature in the field, which are mainly based on measuring the quality of these pesticides as compared to authentic products. Additionally, the study provides a series of guidelines for designing extension programs and advisory services to raise awareness among farmers. While farmers’ actual purchasing rates of fraudulent pesticides have not previously been documented in Egypt, these results are consistent with the country’s 2030 vision of developing an active framework for tackling counterfeit and illegal pesticides on the agricultural market [46].

A growing number of purchases of fraudulent pesticides was observed in the study area. Our findings highlight that an overwhelming number of farmers have suffered from non-deceptive purchasing. The results are consistent with those of Kassem and Alotaibi [12], who found that 73.5% of farmers have purchased fraudulent pesticides in Saudi Arabia. In Uganda, a study conducted by Ashour et al. [17] found that 41% of farmers believe that local herbicides are counterfeit. This study also showed that among a large sample of herbicides collected, 30% contained less than 75% of the active ingredient advertised. Furthermore, another study conducted a market survey of fraudulent pesticides in Mali and found that counterfeit and illegal pesticides accounted for approximately 26% of all pesticide volumes sold [16]. Another market survey conducted in Egypt to monitor the counterfeit situation for a pesticide widely used in Egypt (abamectin) [39] showed that among the samples collected, 42.86% were not registered through the Egyptian Agricultural Pesticides Committee. Additionally, the percentage of the active ingredient in 71.4% of the samples was less than the acceptable limit, while 14.3% of the samples did not contain any abamectin. This result might be due to the fact that more than half of the farmers did not have good education (Table 1). Less-educated farmers do not have the capability of increasing their knowledge about the efficiency of counterfeits or reading label information, or, consequently, differentiating between original and fake products. Moreover, this result might also be because the majority of farmers rely on pesticide retailers as the main source of information about pesticides (Table 1). Pesticide dealers may not be considered as a trusted source for information in some cases. As indicated by Lekei et al. [47], some pesticide retailers, particularly unauthorized shops, may deceive farmers about the performance and effectiveness of pesticides in order to guide them toward certain products in pursuit of profit and as a kind of product advertisement. Meanwhile, as noticed during the field study, some dealers offer pesticides to farmers on a credit basis. This method may build trust-based relationships. The findings also highlighted that among those farmers who purchased fraudulent pesticides, the majority of them expressed that they had purchased such pesticides due to their low price. This might be a result of those farmers purchasing these pesticides for their price advantage in the belief that their quality is satisfactory. This result is consistent with the results of [28], who confirmed that the financial and accessibility criteria ranked second after the performance and effectiveness criteria in terms of importance when farmers select and use pesticides. Therefore, pesticide companies should adopt price-related anti-counterfeiting measures by implementing two mechanisms: first, by introducing lower-price product entry lines to reduce price gaps; second, by reviewing and reducing market, transaction, and production costs to minimize the risk of others undercutting the cost of the product [48,49,50].

Table 1. Socioeconomic profile of the respondents.

| Variable | Frequency (n = 468) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age (min. = 30; max. = 79; mean = 56.23; SD = 9.04) | ||

| <45 years | 33 | 7.1 |

| 45–60 years | 296 | 63.2 |

| >60 years | 139 | 29.7 |

| Education | ||

| Illiterate | 163 | 34.8 |

| Read and write | 137 | 29.3 |

| Basic education | 36 | 7.7 |

| Secondary school | 52 | 11.1 |

| University | 80 | 17.1 |

| Farm size (min. = 0.4; max. =8; mean = 2.61; SD = 1.73) | ||

| <1 hectare | 261 | 55.8 |

| 1–3 hectares | 106 | 22.6 |

| >3 hectares | 101 | 21.6 |

| Off-farm income | ||

| Yes | 266 | 56.8 |

| No | 202 | 43.2 |

| Farming experience (min. = 5; max. = 55; mean = 25.72; SD = 10.51) | ||

| <16 years | 101 | 21.6 |

| 16–30 years | 239 | 51.1 |

| >30 years | 128 | 27.4 |

| Type of agricultural production | ||

| Crops | 225 | 48.1 |

| Vegetables | 80 | 17.1 |

| Fruits | 163 | 34.8 |

| Information sources on pesticides * | ||

| Other farmers | 197 | 42.1 |

| Extension | 183 | 39.1 |

| Input dealers | 329 | 70.3 |

| TV and social media | 133 | 28.4 |

| Private companies | 119 | 25.4 |

| Pesticide’s label | 97 | 20.7 |

| Training experience in pesticides | ||

| Yes | 82 | 17.5 |

| No | 386 | 82.5 |

* More than one answer was allowed; percentages of the categories do not sum up to 100%.

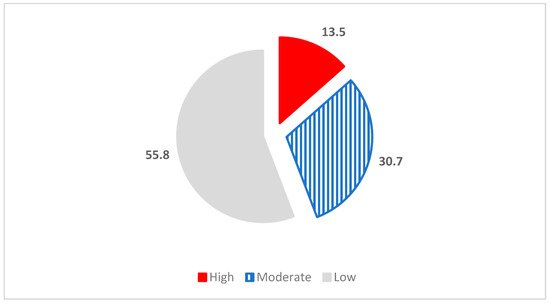

However, the use of visual inspection for detecting fraudulent products is the first step in an overall strategy against fraudulent pesticides, even though this approach is not reliable for detecting counterfeits in most cases. In this context, our findings show that most farmers identify fraudulent pesticides based on their low efficiency, which may indicate that there is resistance to it. This means that farmers face difficulties in accurately identifying fraudulent pesticides during phase of the cycle from purchasing to spraying. This might be because farmers lack sufficient knowledge of the different methods of counterfeiting. Furthermore, we doubt that a farmer would go through a list of chemicals to check that everything was legal. According to Figure 2 in this paper, most farmers do not know how to clearly detect frauds through a visual assessment of the product label and packaging. Furthermore, according to Figure 1, over three-fourths of farmers make their assessment after spraying in their fields, based on the poor results obtained. But many other factors affect spraying efficacy—including time of day, wind speed, and nozzle settings. Poor application methods rather than fraud are possibly to blame for poor pest control results. Ashour et al. [17], for example, found only a weak relationship between farmer assessment of fraud levels and the actual quality of the herbicide glyphosate found in the local market. In fact, distinguishing counterfeits is even more difficult and, in most cases, requires dogs or lab testing, unless the fake is so poor. This conclusion was confirmed by the survey work conducted in Mali on this issue by Haggblade et al. [16], who took suspected counterfeits to the local registered importers for assessment. The results showed that importers could not tell, in some cases, whether the products were counterfeit or authentic from the label alone. To really know, they had to pull a sample from the bottle and test the chemical signature—not necessarily of the active ingredient, but of all of the co-formulants as well. Their labs could distinguish counterfeits readily from the spectrometry. However, simple visual inspection of the label is not always reliable, even for authorized importers. Besides lab testing methods such as biological and physiological indicators, there are chemical signatures, breakdown spectroscopy, and near-infrared spectroscopy [51,52]. Over the past few decades, a variety of digital anti-counterfeiting measures have been developed, from barcodes to holograms, radio frequency identification tags, and invisible pigments, inks, and infrared markers, and more recently, embedded nanotechnology-based solutions to ensure the full traceability and accurate detection of fraudulent products [9,53,54,55]. However, such techniques could be stand-alone systems that do not encourage collaboration among stakeholders in overcoming challenges such as developing a uniform protocol for inspection, surveillance, and monitoring, and using a platform to register pesticides [54,56,57].

Figure 1. Timeliness and method of identifying fraudulent pesticides (by the farmers who purchased fraudulent pesticides).

Figure 2. Level of the farmers’ recognition regarding fraudulent pesticides.

To protect agribusiness against fraudulent pesticides, farmers are strongly advised by authorities to follow the recommended precautions to minimize the risks of buying and using these pesticides. Examining recognition level enabled an assessment of the extent to which respondents were practicing precaution recommendations. In particular, a medium variation in the respondents’ recognition of fraudulent pesticides was observed in the present study. Specifically, farmers’ recognition level had fallen to a low or moderate level for all of the practices investigated. This might be attributed to the farmers’ lack of knowledge about the importance of anti-counterfeiting measures as the main component of combating counterfeit and illegal pesticides on the market. Other possible explanations for this result could be due to the farmers’ inability to visually distinguish a legitimate product from a sophisticated fake copy due to the continuous improvement of counterfeit technology. The findings are in agreement with those of Zimba and Zimudzi [58], who argued that 22.7% of Zimbabwean farmers stated that they could distinguish between counterfeit and genuine pesticides to a large extent. Gharib [59] emphasized the need for awareness-raising and education activities for farmers on how to identify high-quality genuine agricultural inputs. Such programs may be particularly valuable for helping farmers make informed purchasing decisions when fraudulent pesticides exist on the market [26]. This education should also include a clear indication of who to contact for further information or a recommendation to report any suspicions in relation to fraudulent pesticides [60]. Globally, several industry-led initiatives have been piloted to address counterfeiting. The end-user authentication initiative conducted in Ghana is one example of verifying brand schemes [23]. In this initiative, CropLife (funded by Bayer) piloted the use of “Holospots” on Confidor, an insecticide for cocoa. Each container was marked with a hologram, which was verified by viewing under direct light and tilting the label. The user then texts in the numerical code shown to assess the authenticity of the product results.

The results of the binary logistic regression model indicated that the farming experience variable holding all other things constant is an important factor that influences farmers’ purchasing behavior regarding fraudulent pesticides. The variable of farming experience positively influenced their purchasing behavior and was statistically significant at the 1% significance level (p = 0.001). The coefficient of the farming experience of the farmers was positively associated with their purchasing behavior regarding fraudulent pesticides, which indicates the orientation toward non-purchasing among the more experienced farmers. An additional year in the farming experience of the farmers increased the log odds of not purchasing fraudulent pesticides (versus purchasing) by approximately 0.891 times (odds ratio = 891). Again, the farmers who had purchased fraudulent pesticides had a lower mean level of farming experience when compared to those who had not. A probable explanation for this finding is that more experienced farmers are more concerned about the health effects of fraudulent pesticides, as well as more aware of authorized and trusted pesticide shops compared to less experienced farmers. Previous studies have examined farmers’ pesticide use and safety behavior, providing similar evidence to our findings [61,62,63,64].

The variable of education significantly and positively influenced the purchasing behavior regarding fraudulent pesticides. A higher level of education was associated with farmers being more likely not to purchase fraudulent pesticides, in comparison to the group of less-educated farmers. When an additional year of education was attained by the farmers, the results showed that such farmers were approximately 1.2 time (odds ratio = 1.121) more likely not to purchase fraudulent pesticides (statistically significant at the 1% significance level (p = 0.00). Education is a helpful tool for farmers in analyzing the risks associated with the use of fraudulent pesticides, following the features and methods of recognition (visual inspection and analytical methods, as possible), and making decisions about the best options to purchase [17,60]. These results are in line with other studies that examined farmers’ behavior in pesticide use in general, such as the works by [29,31,65,66].

The results showed that the variable of farmers’ recognition of fraudulent pesticides was positively related to the likelihood of a farmer not purchasing such pesticides. The results in Table 2 show that those farmers who had higher recognition levels were more likely not to purchase fraudulent pesticides by approximately 1.795 times (odds ratio = 1.795) (statistically significant at the 1% level (p = 0.00) compared to farmers who had lower recognition levels. This shows that in terms of the non-purchase of fraudulent pesticides, as farmers’ recognition level changed in a positive way, they were more likely not to purchase such pesticides. These results confirm the findings of [12,16], who found that farmers’ adoption of recommended precautions during the purchase of pesticides had an effect on their fight against counterfeit and illegal pesticides on the market, suggesting that farmers’ recognition could be linked to their avoidance of the purchase of fraudulent pesticides.

Table 2. Factors influencing the purchasing of fraudulent pesticides.

| Variable | Coefficients | Odds Ratio | Std. Err. | z | p > z |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | –25.734 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 36.384 | 0.000 |

| Age | –0.315 | 0.730 | 0.572 | 0.320 | 0.572 |

| Farm size | –0.004 | 0.996 | 0.088 | 2.916 | 0.088 |

| Farming experience | 0.116 ** | 0.891 | 0.001 | 11.741 | 0.001 |

| Recognition | 0.468 ** | 1.597 | 0.000 | 56.556 | 0.000 |

| Off-farm income | –1.222 | 0.295 | 0.060 | 3.541 | 0.060 |

| Education level | 0.191 ** | 1.211 | 0.000 | 23.218 | 0.000 |

| Extension as a source of information | 0.083 | 1.087 | 0.887 | 0.020 | 0.887 |

| Pesticide training experience | 0.782 | 2.186 | 0.492 | 0.473 | 0.492 |

| Perception of risks | –0.040 | 0.961 | 0.032 | 1.511 | 0.219 |

| Chi-square (9) = 423.84 **; Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.873; Log likelihood = 113.26 | |||||

** means statistically significant at 1%.

This study has certain limitations that should be taken into account. First is the inclusion of data only from a random sample of farmers from one governorate, which means that the study cannot be generalized to a national level or to other countries. Second, we analyzed their purchasing behavior using a dichotomous question (yes/no). This approach did not allow us to accurately measure the continuity of purchasing. In other words, we were unable to differentiate between a farmer who purchased fraudulent pesticides many times and a farmer who had purchased them only once. Therefore, future studies should include the intensity of purchasing during a specific period. Third, this study relied mainly on self-reports of farmers’ recognition levels. This led to an inability to assess whether farmers were able to correctly detect fraudulent pesticides. Thus, future studies should examine the relationship between farmers’ recognition level and the measured quality. Finally, many more factors such as subjective norms, beliefs and values, costs and benefits, behavioral control, and government policy are also worth investigating.

3. Conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, this study is one of the first to examine farmers’ recognition and purchasing behaviors regarding fraudulent pesticides. Our findings highlight that despite Egyptian farmers having a high perception of the health and environmental risks associated with fraudulent pesticides, the percentage of farmers who have experienced the purchase of such pesticides is high. Some of the key reasons for the use of non-genuine pesticides are difficulty in differentiating between genuine and non-genuine pesticides, the influencing power of distributors/retailers, and the low price of non-genuine pesticides. However, an in-depth examination of the influence of independent variables on farmers’ purchasing behavior indicated that farmers with more experience in recognizing fraudulent pesticides were more likely not to purchase these pesticides. In the same sense, non-purchasing behavior was positively associated with age and farming experience. In a practical sense, this study provides insights into the role that should be followed by farmers to tackle fraudulent pesticides, particularly during the purchasing stage. The policy implications of this study are multifold. Given that most farmers rely on pesticide retailers for information on pesticides, the government, along with different stakeholders, should organize training programs for the recognition of fraudulent pesticides. Moreover, developing an up-to-date list of all legally registered pesticides as well as implementing random inspection over pesticide distribution enterprises should be carried out. For farmers, awareness campaigns using new information technologies are required. These programs should aim to enhance knowledge among farmers about the negative consequences of using fraudulent pesticides, the main types of fraudulent pesticides, the features and methods of recognition, the authentication of the genuineness of pesticides through mobile phones, and how farmers can notify authorities of suspicious pesticides or activity. Due to the scarcity of research on farmers’ behavior with regard to fraudulent pesticides, more research in this area is needed to bring more diverse perspectives from different countries. This study shows the need for more comprehensive empirical research to estimate the amount of fraudulent pesticides in circulation rather than relying on a simple yes/no variable, by conducting a quantitative assessment to estimate the levels of fraud and disaggregating the results by active ingredient. Finally, suggesting an intervention framework for combating fraudulent pesticides in the context of agricultural knowledge and innovation systems could also be an interesting topic to consider.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy11091882

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!