Cyberlindnera jadinii is widely used as a source of single-cell protein and is known for its ability to synthesize a great variety of valuable compounds for the food and pharmaceutical industries. Its capacity to produce compounds such as food additives, supplements, and organic acids, among other fine chemicals, has turned it into an attractive microorganism in the biotechnology field.

- Cyberlindnera jadinii

- phylogeny

- life cycle

- genome

- physiology

- biotechnology applications

- membrane transporter systems

Introduction

The future of our society challenges researchers to find novel technologies to address global environmental problems, mitigate ecosystems’ damage, and biodiversity losses, as the current model of development based on natural resources exploitation is unsustainable. Exploring microorganisms for the production of platform chemicals constitutes an alternative approach to avoid the use of nonrenewable petrochemical-based derivatives. Developing applications for the industrial sphere using biological systems instead of classical chemical catalysts is the main focus of white biotechnology [1]. In microbial-based industrial processes, several features have to be addressed to obtain robust cell factories capable of achieving superior metabolic performances, such as the optimization of metabolic fluxes, membrane, and transporter engineering, and increased tolerance against harsh industrial conditions and toxic compounds [2]. In addition, specifications like the cost of feedstock, product yield and productivity, and downstream processing have to be taken in account to develop successful industrial approaches [1]. Withal the fact that Saccharomyces cerevisiae is by far the most relevant industrial yeast species, Cyberlindnera jadinii is an example of the so-called non-Saccharomyces yeasts [3] claiming for a place as a relevant contributor to the industrial biotechnological sector. The yeast C. jadinii is able to produce valuable bioproducts being an attractive source of biomass enriched in protein and vitamins. The richness of protein content, around 50% of dry cell weight, and amino acid diversity turn its biomass ideal as a source of protein supplement for animal feed and human consumption [4]. The high degree of tolerance to environmental changes occurring during fermentation turn C. jadinii an alternative to other established cell factory systems [5]. As a Crabtree-negative yeast, it has one of the highest respiratory capacities among characterized yeast species, being considered ideal for continuous cell cultures [6]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) attributed the “General Regarded as Safe” (GRAS) status to this yeast, recognizing it as safe and suitable for supplying food additives and dietary supplements for humans [5][7][8][9]. The ability to produce relevant compounds, to grow in a wide range of temperatures, to use inexpensive media with high productivity levels turns it an industrially relevant microorganism [8][10][11][12]. Recent efforts have developed C. jadinii molecular tools for metabolic engineering processes and the overexpression of proteins. In the past, the uncertainty of this yeast polyploidy, together with the lack of suitable selection markers and expression cassettes, [10] delayed its widely use as cell factory. With this review, we intend to compile the existing knowledge on this yeast, that will allow the development of future strategies to strengthen the role of C. jadinii in the biotechnology sector. We start by reviewing the nomenclature of this species, altered several times over time. An update on the current nomenclature of the most relevant strains is also presented. We establish the evolutionary relationship of C. jadinii within other fungi with a complete genome available. The most relevant morphological and physiological traits are also here described, together with the genetic manipulation tools and expression systems currently available. Moreover, we present a summary of all the plasma membrane transporter systems so far characterized in this yeast, as they are key-players for cell factory optimization. Finally, we will focus on the biotechnological potential of this yeast and highlight the future challenges to achieve the full exploitation of this industrially valuable microorganism.

Ecology, Taxonomy, and Evolution

The natural environment of Cyberlindnera jadinii is still an open question. It is thought that it may be associated with the decomposition of plant material in nature, as it is able to assimilate pentoses and tolerate lignocellulosic by-products [3], displays great fermentative ability, and is copiotrophic [13]. The current laboratory strains were isolated from distinct environments, namely, from the pus of a woman abscess (CBS 1600/NRRL Y-1542), a cow with mastitis (CBS 4885/NRRL Y-6756), a yeast deposit from a distillery (CBS 567), yeast cell factories (CBS 621), and flowers (CBS 2160) [5][6][7][8][9][12]. The extensive nomenclature revisions of this species are well described in “The tortuous history of Candida utilis” by Barnet [14]. In 1926, this yeast was isolated from several German yeast factories, which had been cultivated without a systematic name during the time of World War I for food and fodder [14]. It was first named Torula utilis being later referred to as Torulopsis utilis (1934). The “food yeast” was also designated as Saccharomyces jadinii (1932), Hansenula jadinii (1951), Candida utilis (1952), Pichia jadinii (1984), and Lindnera jadinii (2008) [12][14][15][16]. From the aforementioned, C. utilis was the nomenclature most commonly used, having almost 1000 published papers in PubMed (results available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/?term=%22candida+utilis%22; Accessed 16 October 2020). The Candida genus comprised species that form pseudohyphae or true hyphae with blastoconidia, among other standard characteristics [17][18][19]. In the classification system implemented in 1952 by Lodder and Kreger-van Rij, the Candida genus included yeasts that produce only simple pseudohyphae [14]. At that time, the majority of the isolates was renamed as C. utilis [18]. Later, the C. utilis was established as an asexual state of a known ascosporogenous yeast, Hansenula jadinii, as it was found to share some similarities between phenotypic traits [20]. In 1984, even though concurring with a publication of an extensive chapter of the genus Hansenula, Kurtzman moved most of the Hansenula species to the Pichia genus, due to their “deoxyribonucleic acid relatedness.” Thus, C. utilis was renamed Pichia jadinii. A quarter of a century later, this yeast species was again renamed as Lindnera jadinii based on analyses of nucleotide sequence divergence in the genes coding for large and small-subunit rRNAs [12]. Species integrated into the Lindnera differ considerably in ascospore morphology ranging from spherical to hat-shaped or Saturn-shaped spores. In addition, this clade includes both hetero- and homothallic species and physiological features as fermenting glucose and assimilating a variety of sugars, polyols, and other carbon sources are defining characteristics of the Lindnera genus [12]. Finally, 1 year later, the genus Lindnera was replaced by Cyberlindnera, as the later homonym defined a validly published plant genus [15]. This substitution occurred in 21 new species, including Cyberlindnera jadinii [15]. In summary, any of the aforementioned nomenclatures reported in the literature may refer to the same organism since C. utilis is the anamorph state and C. jadinii the teleomorph state [14]. The anamorph represents the asexual stage of a fungus contrasting with the teleomorph form that defines the sexual stage of the same fungus [21]. The primary name of a species relies on the sexual state or teleomorph, but a second valid name may rely on the asexual state or anamorph [22]. However, this should only happen when teleomorphs have not been found for a specific species or it is not clear if a particular teleomorph is the same species as a particular anamorph. Accordingly, since 2013, the International Botanical Congress states that the system for allowing separate names for the anamorph state should end [23]. The new International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, the Melbourne Code, supports the directive that fungal species or higher taxon should be assigned with a single valid name. Accordingly, anamorph yeast genera like Candida should be revised to turn the genus consistent with phylogenetic affinities [19]. Notwithstanding, the reclassification of several C. utilis as C. jadinii in several culture type collections is still confusing, reaching a point where the same strain is designated as C. utilis and C jadinii in different culture type collections. This aspect, together with the previous nomenclatures used in research papers, leads to unnecessary misunderstandings. To clarify this, Table 1 presents the alternative designations of the main laboratory strains.

Table 1. Main C. jadinii (former C. utilis) strains described in literature.

| Nomenclature in Literature |

Current Nomenclature | Isolation Source | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Candida utilis NBRC 0988 |

C. jadinii ATCC 9950; CBS 5609; DSM 2361; NBRC 0988; NCYC 707; NRRL Y-900 |

Yeast factory in Germany |

[24] |

| C. utilis ATCC 9256 a | C. jadinii NRRL Y1084; CBS 841; CCRC 20334; DSM 70167; NCYC 359; VKM Y768; VTT C79091 | Unknown | [25][26] |

| C. utilis ATCC 9226 a NBRC 1086 |

C. jadinii VTT C-71015; FMJ 4026; NBRC 1086 | Unknown | [25][27][28] |

| C. utilis IGC 3092 | C. jadinii PYCC 3092; CBS 890; VKM Y-33 | Unknown | [29][30][31] |

| C. utilis CCY 39-38-18 | C. jadinii CCY 029-38-18 b | Unknown | [32] |

| C. utilis NCYC 708 | C. jadinii NCYC 708; ATCC 42181; CBS 5947; VTT C-84157 | Unknown | [33] |

| C. utilis CBS 4885 NRRL Y-6756 |

C. jadinii CBS 4885; NRRL Y-6756; NBRC 10708 | Cow with mastitis | [34] |

| C. utilis CBS 567 NRRL Y-1509 |

C. jadinii CBS 567; NRRL Y-1509 | Yeast deposit in distillery |

[34] |

| C. utilis CBS 2160 | C. jadinii CBS 2160 | Flower of Taraxacum sp. | [34] |

| C. utilis CBS 621 | C. jadinii CBS 621; NRRL Y-7586; ATCC 22023; PYCC 4182 | Yeast factories | [35] |

| C. utilis CBS 1600 | C. jadinii CBS 1600; NRRL Y-1542; ATCC 18201 | Pus of a woman abscess |

[16] |

a This strain has been discontinued in ATCC. b The strain number reported in the literature is not available in the Culture Collection of Yeasts (CCY), all C. jadinii strains are registered as 029-38-XX, including C. jadinii 029-38-18, the likely match to CCY 39-38-18.

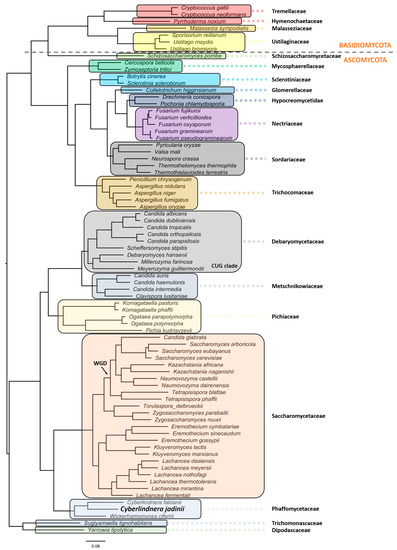

C. jadinii belongs to the phylum Ascomycota, subphylum Saccharomycotina. The members of this subphylum constitute a monophyletic group of ascomycetes that are well defined by ultrastructural and DNA characteristics [13]. These include lower amounts of chitin in overall polysaccharide composition at cell walls, being unable to stain with diazonium blue, low content of guanine and cytosine (G + C < 50%) at nuclear DNA, and presence of continuous holoblastic bud formation with wall layers. C. jadinii belongs to the Saccharomycetes class, Saccharomycetidae family, Saccharomycetales order, and the Cyberlindnera genus. However, a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis and evolutionary relationship are still missing for this species [36][37][38]. Aiming at filling this gap, we performed a robust phylogeny reconstruction [36][39][40][41]. As can be depicted in Figure 1, this yeast localizes in the Phaffomycetaceae clade together with Cyberlindnera fabianii and Wickerhamomyces ciferri. The nearest neighbors belong to the Saccharomycetaceae family, which includes a clade with S. cerevisiae/Torulaspora delbrueckii species and another clade with Eremothecium gossypii (former Ashbya gossypii), Kluyveromyces lactis/marxianus, and Lachancea species. Despite the previous genus nomenclature adopted for C. jadinii (Candida and Pichia), it is phylogenetically distant from the Debaryomycetaceae and Pichiaceae families that include the Candida species, except C. glabrata, the Pichia kudriavzevii, and Ogataea species. Komagataella phaffi is as expected included in the Pichiaceae clade, together with Komagataella pastoris [36][40]. The Trichomonascaceae/ Dipodascaceae clade, formerly known as the Yarrowia clade, includes now the Sugiyamaella lignohabitans species together with Yarrowia lipolytica, and is the most distant yeast clade, except for the Schizosaccharomycetaceae that clusters with all the Basiodiomycota. The filamentous fungi Neurospora crassa and Fusarium graminearum are in different clades as members of the Sordariaceae and Nectriaceae clades, respectively [40]. In addition, in the Sordariaceae clade, the phylogenetic position of Thermothelomyces thermophila species (Myceliophthora thermophila) was uncovered [39][42].

Figure 1. Evolutionary relationship of Cyberlindnera jadinii, a member of the Phaffomycetaceae clade. The phylogenetic reconstruction was obtained using the following parameters: maximum likelihood in IQ-TREE (http://www.iqtree.org), the model of amino acid evolution JTT (Jones-Taylor-Thornton), and four gamma-distributed rates. Homologues were detected for 1567 proteins across the proteome of 77 selected fungal species from NCBI. The 1567 set of proteins were aligned and then concatenated in order to use in the phylogenetic analysis. These proteins offer a clear high-resolution evolutionary view of the different species, as they are essential proteins beyond the specific biology of the different yeasts. Bootstrapping provided values of 100% for all the nodes. Yeast and fungi families are highlighted with different colors and shades. The phylogenetic relationships reflect evolutionary ancestries, independently of adaptations and overall gene contents within the various species. All families with more than one representative species in the analyses formed monophyletic groups.

Morphology and Physiology

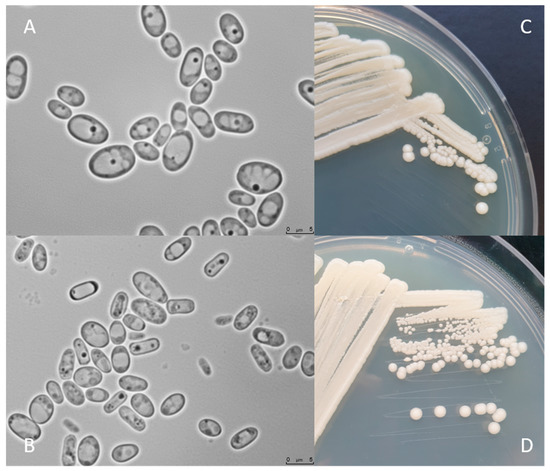

The C. jadinii microscopic view provided by Kurtzman et al. (2011) has shown the diversity of cell shapes and sizes [20][34] after 10–30 days at 25 °C in 5% Malt Extract Agar media. The cell patterns of C. jadinii CBS 1600 varied from ellipsoidal to elongated occurring in single cells or in pairs. Some pseudohyphae forms were also detected with diameter balanced between (2.5–8.0) and (4.1–11.2) µm.

Figure 2 shows C. jadinii DSM 2361 strain cultivated on YPD or Malt Extract Agar media for 3 (A and C) and 12 days (B and D) at 30 °C. The colonies are white, round, with a smooth texture, an entire margin, and a convex elevation trait (C and D). Cells present an ellipsoidal to elongated form, with a diameter between 5 and 7.5 µm (A and B). Yeast cell morphology can be tightly influenced by the environment. These modifications can affect the fermentation performance by inducing rheological changes that can influence mass and heat transfer alterations in the bioreactor [43]. However, in a study performed by Pinheiro et al. (2014), the CBS 621 strain cultured in a pressurized-environment triggered with 12 bar air pressure presented no significant differences in cell size and shape [35]. C. jadinii is a homothallic species and forming hat-shaped ascospores that can be present in a number of one to four in unconjugated deliquescent asci [34]. Cyberlindnera species can assimilate several compounds, namely, sugars and organic acids. The robust fermentation characteristics of C. jadinii allow growth in a diversity of substrates from biomass-derived wastes, including hardwood hydrolysates from the pulp industry, being able to assimilate glucose, arabinose, sucrose, raffinose, and D-xylose [8][9][10][44]. As previously mentioned, C. jadinii is a Crabtree-negative yeast, reaching higher cell yields under aerobic conditions [45][46][47] than Crabtree-positive species. The Crabtree-negative effect favors the respiration process over fermentation, enabling the development of phenotypes relevant for protein production [48]. This species has a high tolerance to elevated temperatures, being able to grow in a broad spectrum of temperatures from 19 to 37 °C [37] and to tolerate long-term mild acid pHs (~3.5) [49]. Another relevant property is the ability to release proteins to the extracellular medium [50]. Significant lipase and protease content were achieved using a wild C. jadinii strain isolated from spoiled soybean oil, using solid-state fermentation [51][52]. C. jadinii assimilates alcohols, acetaldehyde, organic acids, namely, monocarboxylates (DL-lactate), dicarboxylates (succinate), and tricarboxylates (citrate), sugar acids (D-gluconate), and various nitrogen sources comprising nitrate, ammonium hydroxide, as well as amino acids [8][10][12][37]. A set of metabolic advantages, as the high metabolic flux in TCA cycle, the great amino acid synthesis ability, and strong protein secretion turns C. jadinii a yet underexplored host for bioprocesses. An incomplete understanding of genetics, metabolism, and cellular physiology combined with a lack of advanced molecular tools for genome edition and metabolic engineering manipulation of C. jadinii hampered its development for cell factory utilization.

Figure 2. C. jadinii DSM 2361 morphological traits. (A) Microscopic photographs of C. jadinii cells after 3 days (A) and 12 days (B) of growth at 30 °C on yeast extract-peptone-dextrose media. Scale bars are 5.0 µm. Macro-morphological features of C. jadinii after 3 days of growth in YPD (C) and Malt Extract Agar (D) media, at 30 °C.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof7010036

References

- Heux, S.; Meynial-Salles, I.; O’Donohue, M.; Dumon, C. White biotechnology: State of the art strategies for the development of biocatalysts for biorefining. Biotechnol. Adv. 2015, 33, 1653–1670.

- Gong, Z.; Nielsen, J.; Zhou, Y.J. Engineering Robustness of Microbial Cell Factories. Biotechnol. J. 2017, 12.

- Sibirny, A. Non-Conventional Yeasts: From Basic Research to Application; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019.

- Martínez, E.; Santos, J.; Araujo, G.; Souza, S.; Rodrigues, R.; Canettieri, E. Production of Single Cell Protein (SCP) from Vinasse. In Fungal Biorefineries; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 215–238.

- Buerth, C.; Heilmann, C.; Klis, F.; de Koster, C.; Ernst, J.; Tielker, D. Growth-dependent secretome of Candida utilis. Microbiology 2011, 157, 2493–2503.

- Barford, J. The technology of aerobic yeast growth. Yeast Biotechnol. 1987, 200–230.

- Miura, Y.; Kettoku, M.; Kato, M.; Kobayashi, K.; Kondo, K. High level production of thermostable alpha-amylase from Sulfolobus solfataricus in high-cell density culture of the food yeast Candida utilis. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1999, 1, 129–134.

- Bekatorou, A.; Psarianos, C.; Koutinas, A. Production of food grade yeasts. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2006, 44, 407–415.

- Boze, H.; Moulin, G.; Galzy, P. Production of food and fodder yeasts. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 1992, 12, 65–86.

- Buerth, C.; Tielker, D.; Ernst, J. Candida utilis and Cyberlindnera (Pichia) jadinii: Yeast relatives with expanding applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 6981–6990.

- Klein, R.; Faureau, M. Chapter 8: The Candida species: Biochemistry, molecular biology, and industrial applications. In Food Biotechnology: Microorganisms; Hui, Y.H., Khachatourians, G.G., Eds.; Wiley VCH: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 297.

- Kurtzman, C.; Robnett, C.; Basehoar-Powers, E. Phylogenetic relationships among species of Pichia, Issatchenkia and Williopsis determined from multigene sequence analysis, and the proposal of Barnettozyma gen. nov., Lindnera gen. nov. and Wickerhamomyces gen. nov. Fems Yeast Res. 2008, 8, 939–954.

- Suh, S.; Blackwell, M.; Kurtzman, C.; Lachance, M. Phylogenetics of Saccharomycetales, the ascomycete yeasts. Mycologia 2006, 98, 1006–1017.

- Barnett, J. A history of research on yeasts 8: Taxonomy. Yeast 2004, 21, 1141–1193.

- Minter, D. Cyberlindnera, a replacement name for Lindnera Kurtzman et al., nom. illegit. Mycotaxon 2009, 110, 473–476.

- Rupp, O.; Brinkrolf, K.; Buerth, C.; Kunigo, M.; Schneider, J.; Jaenicke, S.; Goesmann, A.; Pühler, A.; Jaeger, K.; Ernst, J. The structure of the Cyberlindnera jadinii genome and its relation to Candida utilis analyzed by the occurrence of single nucleotide polymorphisms. J. Biotechnol. 2015, 211, 20–30.

- Murray, P.; Baron, E.; Pfaller, M.; Tenover, F.; Yolken, R. Manual of Clinical Microbiology, 6th ed.; American Society for Microbiology: Washington, DC, USA, 1995.

- Lodder, J.; Kreger-Van Rij, J.W. The Yeasts, A Taxonomic Study; North Holland Publishing Company: Amesterdam, The Netherlands, 1952.

- Daniel, H.; Lachance, M.; Kurtzman, C. On the reclassification of species assigned to Candida and other anamorphic ascomycetous yeast genera based on phylogenetic circumscription. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 106, 67–84.

- Kurtzman, C.; Johnson, C.; Smiley, M. Determination of conspecificity of Candida utilis and Hansenula jadinii through DNA reassociation. Mycologia 1979, 71, 844–847.

- Deak, T. Characteristics and properties of Foodborne yeasts. In Handbook of Food Spoilage Yeasts; Deak, T., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007.

- Kurtzman, C.; Fell, J.; Boekhout, T. Definition, classification and nomenclature of the yeasts. In The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 3–5.

- Hawksworth, D. Managing and coping with names of pleomorphic fungi in a period of transition. Ima Fungus 2012, 3, 15–24.

- Tomita, Y.; Ikeo, K.; Tamakawa, H.; Gojobori, T.; Ikushima, S. Genome and transcriptome analysis of the food-yeast Candida utilis. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37226.

- Kondo, K.; Saito, T.; Kajiwara, S.; Takagi, M.; Misawa, N. A transformation system for the yeast Candida utilis: Use of a modified endogenous ribosomal protein gene as a drug-resistant marker and ribosomal DNA as an integration target for vector DNA. J. Bacteriol. 1995, 177, 7171–7177.

- Ikushima, S.; Minato, T.; Kondo, K. Identification and application of novel autonomously replicating sequences (ARSs) for promoter-cloning and co-transformation in Candida utilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 152–159.

- Belcarz, A.; Ginalska, G.; Lobarzewski, J.; Penel, C. The novel non-glycosylated invertase from Candida utilis (the properties and the conditions of production and purification). Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 2002, 1594, 40–53.

- Fujino, S.; Akiyama, D.; Akaboshi, S.; Fujita, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Tamai, Y. Purification and characterization of phospholipase B from Candida utilis. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 377–386.

- Leão, C.; Van Uden, N. Transport of lactate and other short-chain monocarboxylates in the yeast Candida utilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1986, 23, 389–393.

- Cássio, F.; Leão, C. Low-and high-affinity transport systems for citric acid in the yeast Candida utilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1991, 57, 3623–3628.

- Cássio, F.; Leão, C. A comparative study on the transport of L (-) malic acid and other short-chain carboxylic acids in the yeast Candida utilis: Evidence for a general organic acid permease. Yeast 1993, 9, 743–752.

- Krahulec, J.; Lišková, V.; Boňková, H.; Lichvariková, A.; Šafranek, M.; Turňa, J. The ploidy determination of the biotechnologically important yeast Candida utilis. J. Appl. Genet. 2020, 61, 275–286.

- Ross, I.; Parkin, M. Uptake of copper by Candida utilis. Mycol. Res. 1989, 93, 33–37.

- Kurtzman, C. Chapter 42—Lindnera Kurtzman, Robnett & Basehoar-Powers (2008). In The Yeasts: A Taxonomic Study; Kurtzman, C., Fell, J., Boekhout, T., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 521–543.

- Pinheiro, R.; Lopes, M.; Belo, I.; Mota, M. Candida utilis metabolism and morphology under increased air pressure up to 12 bar. Process Biochem. 2014, 49, 374–379.

- Hittinger, C.; Rokas, A.; Bai, F.; Boekhout, T.; Gonçalves, P.; Jeffries, T.; Kominek, J.; Lachance, M.; Libkind, D.; Rosa, C. Genomics and the making of yeast biodiversity. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2015, 35, 100.

- Riley, R.; Haridas, S.; Wolfe, K.; Lopes, M.; Hittinger, C.; Göker, M.; Salamov, A.; Wisecaver, J.; Long, T.; Calvey, C. Comparative genomics of biotechnologically important yeasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 9882–9887.

- Shen, X.; Opulente, D.; Kominek, J.; Zhou, X.; Steenwyk, J.; Buh, K.; Haase, M.; Wisecaver, J.; Wang, M.; Doering, D. Tempo and mode of genome evolution in the budding yeast subphylum. Cell 2018, 175, 1533–1545.e20.

- Marcet-Houben, M.; Gabaldón, T. Evolutionary and functional patterns of shared gene neighbourhood in fungi. Nat. Microbiol. 2019, 4, 2383–2392.

- Shen, X.; Zhou, X.; Kominek, J.; Kurtzman, C.; Hittinger, C.; Rokas, A. Reconstructing the backbone of the Saccharomycotina yeast phylogeny using genome-scale data. G3 GenesGenomesGenet. 2016, 6, 3927–3939.

- Alves, R.; Sousa-Silva, M.; Vieira, D.; Soares, P.; Chebaro, Y.; Lorenz, M.; Casal, M.; Soares-Silva, I.; Paiva, S. Carboxylic Acid Transporters in Candida Pathogenesis. MBio 2020, 11, e00156-00120.

- Thanh, V.; Thuy, N.; Huong, H.; Hien, D.; Hang, D.; Anh, D.; Hüttner, S.; Larsbrink, J.; Olsson, L. Surveying of acid-tolerant thermophilic lignocellulolytic fungi in Vietnam reveals surprisingly high genetic diversity. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3674.

- Coelho, M.; Amaral, P.; Belo, I. Yarrowia lipolytica: An industrial workhorse. In Current Research, Technology and Education Topics in Applied Microbiology and Microbial Biotechnology; Méndez-Vilas, A., Ed.; Formatex: Badajoz, Spain, 2010; Volume 2, pp. 930–940.

- Andreeva, E.; Pozmogova, I.; Rabotnova, I. Principle growth indices of a chemostat Candida utilis culture resistant to acid pH values. Mikrobiologiia 1979, 48, 481.

- Verduyn, C. Physiology of yeasts in relation to biomass yields. In Quantitative Aspects of Growth and Metabolism of Microorganisms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 325–353.

- Ordaz, L.; Lopez, R.; Melchy, O.; Torre, M. Effect of high-cell-density fermentation of Candida utilis on kinetic parameters and the shift to respiro-fermentative metabolism. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2001, 57, 374–378.

- Dashko, S.; Zhou, N.; Compagno, C.; Piškur, J. Why, when, and how did yeast evolve alcoholic fermentation? Fems Yeast Res. 2014, 14, 826–832.

- Gomes, A.; Carmo, T.; Carvalho, L.; Bahia, F.; Parachin, N. Comparison of yeasts as hosts for recombinant protein production. Microorganisms 2018, 6, 38.

- Wang, D.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Y.; Wei, G.; Qi, B. Glutathione is involved in physiological response of Candida utilis to acid stress. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 10669–10679.

- Kunigo, M.; Buerth, C.; Tielker, D.; Ernst, J. Heterologous protein secretion by Candida utilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 7357–7368.

- Moftah, O.; Grbavčić, S.; Žuža, M.; Luković, N.; Bezbradica, D.; Knežević-Jugović, Z. Adding value to the oil cake as a waste from oil processing industry: Production of lipase and protease by Candida utilis in solid state fermentation. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2012, 166, 348–364.

- Grbavčić, S.; Dimitrijević-Branković, S.; Bezbradica, D.; Šiler-Marinković, S.; Knežević, Z. Effect of fermentation conditions on lipase production by Candida utilis. J. Serb. Chem. Soc. 2007, 72, 757–765.

- Mukherjee, P.; Chandra, J.; Retuerto, M.; Sikaroodi, M.; Brown, R.; Jurevic, R.; Salata, R.; Lederman, M.; Gillevet, P.; Ghannoum, M. Oral mycobiome analysis of HIV-infected patients: Identification of Pichia as an antagonist of opportunistic fungi. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1003996.

- De Jesus, M.; Rodriguez, A.; Yagita, H.; Ostroff, G.; Mantis, N. Sampling of Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis by langerin-positive dendritic cells in mouse Peyer’s patches. Immunol. Lett. 2015, 168, 64–72.

- Thévenot, J.; Cordonnier, C.; Rougeron, A.; Le Goff, O.; Nguyen, H.; Denis, S.; Alric, M.; Livrelli, V.; Blanquet-Diot, S. Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection has donor-dependent effect on human gut microbiota and may be antagonized by probiotic yeast during interaction with Peyer’s patches. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 9097–9110.

- Buerth, C.; Mausberg, A.; Heininger, M.; Hartung, H.; Kieseier, B.; Ernst, J. Oral tolerance induction in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with Candida utilis expressing the immunogenic MOG35-55 peptide. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0155082.

- Feng, T.; Elson, C. Adaptive immunity in the host–microbiota dialog. Mucosal Immunol. 2011, 4, 15.

- Singh, R.; Singh, T.; Singh, A. Chapter 9—Enzymes as Diagnostic Tools. In Advances in Enzyme Technology; Singh, R.S., Singhania, R.R., Pandey, A., Larroche, C., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 225–271.

- Żymańczyk-Duda, E.; Brzezińska-Rodak, M.; Klimek-Ochab, M.; Duda, M.; Zerka, A. Yeast as a Versatile Tool in Biotechnology. Yeast Ind. Appl. 2017, 1, 3–40.

- Khan, T.; Daugulis, A. Application of solid–liquid TPPBs to the production of L-phenylacetylcarbinol from benzaldehyde using Candida utilis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2010, 107, 633–641.

- Tripathi, C.; Agarwal, S.; Basu, S. Production of L-phenylacetylcarbinol by fermentation. J. Ferment. Bioeng. 1997, 84, 487–492.

- Shin, H.; Rogers, P. Biotransformation of benzeldehyde to L-phenylacetylcarbinol, an intermediate in L-ephedrine production, by immobilized Candida utilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1995, 44, 7–14.

- Rogers, P.; Shin, H.; Wang, B. Biotransformation for L-ephedrine production. In Biotreatment, Downstream Processing and Modelling; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; pp. 33–59.

- Lamping, E.; Monk, B.; Niimi, K.; Holmes, A.; Tsao, S.; Tanabe, K.; Niimi, M.; Uehara, Y.; Cannon, R. Characterization of Three Classes of Membrane Proteins Involved in Fungal Azole Resistance by Functional Hyperexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 2007, 6, 1150–1165.

- Watanasrisin, W.; Iwatani, S.; Oura, T.; Tomita, Y.; Ikushima, S.; Chindamporn, A.; Niimi, M.; Niimi, K.; Lamping, E.; Cannon, R. Identification and characterization of Candida utilis multidrug efflux transporter CuCdr1p. Fems Yeast Res. 2016, 16, fow042.

- Hong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Farh, L.; Yang, W.; Liao, C.; Shiuan, D. Recombinant Candida utilis for the production of biotin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2006, 71, 211.

- Shimada, H.; Kondo, K.; Fraser, P.; Miura, Y.; Saito, T.; Misawa, N. Increased Carotenoid Production by the Food Yeast Candida utilis through Metabolic Engineering of the Isoprenoid Pathway. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 2676–2680.

- Miura, Y.; Kondo, K.; Saito, T.; Shimada, H.; Fraser, P.; Misawa, N. Production of the carotenoids lycopene, β-carotene, and astaxanthin in the food yeast Candida utilis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1998, 64, 1226–1229.

- Kondo, K.; Miura, Y.; Sone, H.; Kobayashi, K. High-level expression of a sweet protein, monellin, in the food yeast Candida utilis. Nat. Biotechnol. 1997, 15, 453.

- Li, Y.; Wei, G.; Chen, J. Glutathione: A review on biotechnological production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2004, 66, 233–242.

- Kogan, G.; Šandula, J.; Šimkovicová, V. Glucomannan from Candida utilis. Folia Microbiol. 1993, 38, 219–224.

- Ruszova, E.; Pavek, S.; Hajkova, V.; Jandova, S.; Velebny, V.; Papezikova, I.; Kubala, L. Photoprotective effects of glucomannan isolated from Candida utilis. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 501–511.

- Ikushima, S.; Fujii, T.; Kobayashi, O.; Yoshida, S.; Yoshida, A. Genetic engineering of Candida utilis yeast for efficient production of L-lactic acid. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2009, 73, 1818–1824.

- Tamakawa, H.; Ikushima, S.; Yoshida, S. Efficient production of L-lactic acid from xylose by a recombinant Candida utilis strain. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2012, 113, 73–75.

- Kunigo, M.; Buerth, C.; Ernst, J. Secreted xylanase XynA mediates utilization of xylan as sole carbon source in Candida utilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 99, 8055–8064.

- Tamakawa, H.; Ikushima, S.; Yoshida, S. Ethanol production from xylose by a recombinant Candida utilis strain expressing protein-engineered xylose reductase and xylitol dehydrogenase. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 1994–2000.

- Hui, Y.H.; Khachatourians, G. Food Biotechnology: Microorganisms; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1994.

- Maugeri-Filho, F.; Goma, G. SCP production from organic acids with Candida utilis. Rev. Microbiol. 1988, 19, 446–452.

- Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Guo, Z.; Zeng, S.; Tian, Y.; Zheng, B. Application of Candida utilis to Loquat Wine Making and Making Method for Loquat Wine. CN Patent Application Number 201210131375.2, 28 April 2012.

- Xie, B.; He, B.; Hu, J.; Yu, Q.; Huang, Q.; Zhang, Y. Dry Loquat Wine and Making Method Thereof. CN Patent Application Number 201410808872.0, 1 April 2015.

- Cai, Y.; Jiang, X.; Chen, Y.; Chen, Q.; Cai, Y.; Cai, Y. Preparation Method of Alcohol-Free Fruit Wine Being Rich in Lovastatin. CN Patent Application Number 201810869936.6, 29 January 2019.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Body Lotion Containing Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810110524.4, 8 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Sunscreen Cream with Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810110525.9, 12 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Facial Cleanser Containing Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810113250.4, 8 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Toner Containing Beta-D-glucan of Candida utilis. CN Patent Application Number 201810113263.1, 22 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Eye Cream Containing Beta-D-glucan of Candida utilis. CN Patent Application Number 201810113248.7, 22 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Shampoo Containing Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810110923.0, 14 August 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L. Body Wash with Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810110925.X, 15 June 2018.

- Ma, X.; Liu, L.; Shao, L.; He, Y. Hand Care Cream with Candida utilis Beta-D-glucan. CN Patent Application Number 201810110885.9, 15 June 2018.

- Li, S.; Pang, H.; Liu, S. Preparation Method of Recombinant Uricase. CN Patent Application Number 201410535887.4, 11 February 2015.

- Liu, J.; Gao, X.; Shang, F.; Liu, P.; Zhu, M. Candida utilis Reduction Method for Producing Methyl Fluorophenyl Methyl Propionate. CN Patent Application Number 201410518177.0, 14 January 2015.

- Firgatovich, B.F.; Gennadevich, G.Y.; Yurevna, G.E.; Mikhajlovna, K.E. Organomineral Granular Fertilizer. Russian Patent Application Number 2019143533, 25 June 2020.

- Bai, L.; Liu, X.; Jiang, H.; Liu, H.; Deng, Y. Application of Microorganism Bacterium Agent Capable of Efficiently Converting Form of Cadmium in Contaminated Soil Biologically. CN Patent Application Number 201710284861.0, 18 August 2017.

- Cui, G.; Gu, Y.; Cui, C.; Zhou, Y. Microbial Soil Conditioner for Lithified Soil. CN Patent Application Number 201310638420.8, 3 June 2015.