Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Oncology

The advancement in therapy has provided a dramatic improvement in the rate of recovery among cancer patients. However, this improved survival is also associated with enhanced risks for cardiovascular manifestations, including hypertension, arrhythmias, and heart failure. The cardiotoxicity induced by chemotherapy is a life-threatening consequence that restricts the use of several chemotherapy drugs in clinical practice.

- anticancer drugs

- cardiotoxicity

- pharmacogenetics

- radiation therapy

- chemotherapeutic agent

1. Introduction

The advancement of medical science is associated with a paradigm shift in new anticancer therapies, causing a significant increase in long life expectancy in patients. Though a tremendous improvement has happened in cancer chemotherapy, the serious adverse effects associated with the therapy are still a major challenge [1,2,3]. Earlier studies reported a 0.5% prevalence rate of cancer in the general population with a mortality rate of 25%. The cytotoxic effects of the therapy affect all major organs and the clinical manifestations are associated with the development of co-morbidities [4]. Since cardiotoxicity is the most common adverse effect manifested by anticancer drug therapy, the increase in life expectancy owing to anticancer therapy may be negated by the enhanced death rate due to heart issues [5,6]. Cardiotoxicity can strike at any point during pharmacological treatment, with symptoms ranging from modest myocardial dysfunction to permanent heart failure and death [6].

The principle involved in chemotherapy is that it impairs the metabolic and mitotic processes of cancer cells and, in maximum cases, it also damages normal cells and tissues, which leads to various side effects ranging from mild to severe forms of gastrointestinal upset, the suppression of bone marrow, in addition to cardiovascular toxicities including myocardial dysfunction, heart failure, hypertension, and tachyarrhythmia [2,7].

Cancer therapies, including molecular target therapies, cytotoxic chemotherapy, and mediastinal irradiation, are seen to be linked with myocyte damage, ischemia, conduction and rhythm disturbances, left ventricular dysfunction, cardiac failure, and several other cardiovascular complications [3,8,9].

Various biochemical investigations into the different pathways of cardiovascular damage have been documented. Chemotherapeutic drugs cause cardiotoxicity by enhancing the formation of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RON), which impairs redox equilibrium. Although peroxisomes and other subcellular components are critical regulators of redox equilibrium, mitochondria remain the prime targets for anticancer-induced cardiotoxicity [10].

Anthracyclines (ANT) (doxorubicin), alkylating drugs (cyclophosphamide, cisplatin), and taxanes (paclitaxel, docetaxel) are the most common chemotherapeutic medications linked to serious cardiac events. More than half of the currently used anticancer therapies include anthracyclines, which cover breast cancer, sarcoma, gynecological cancer, and lymphoma [11].

2. Mode of Cardiotoxicity Induction

2.1. Cyclophosphamide-Induced Carditoxicity

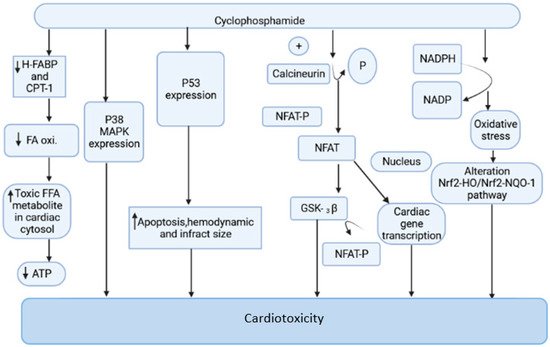

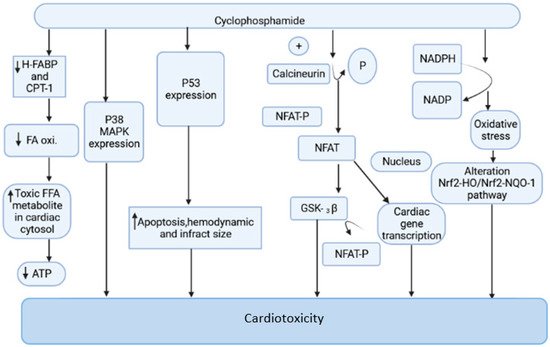

Cyclophosphamide is an anticancer drug with antitumor properties that is commonly used in humans for a range of neoplasms [12]. However, multiple reports have indicated that, in addition to having tumor-selective properties, cyclophosphamide has a slew of highly hazardous adverse manifestations (Figure 1), the most serious of which is cardiotoxicity [13].

Figure 1. The mechanism of cyclophosphamide-mediated cardiac toxicity.

Cyclophosphamide is activated by the cytochrome P-450 (CYP) enzyme in the liver, which transforms it into 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide. Aldo cyclophosphamide (AldoCY) and 4-hydroxycyclophosphamide are in equilibrium. AldoCY may be oxidized by aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) to the inactive metabolite o-carboxymethylphosphoramide mustard (CEPM) or beta eliminated through a chemical mechanism that decomposes to produce cytotoxic phosphoramide mustard (PM) and the byproduct acrolein, depending on the cell type [14]. The antineoplastic activity of cyclophosphamide is due to the presence of phosphoramide mustard, which is the therapeutic metabolite in the active form present in cyclophosphamide, and it shows DNA alkylation activity, whereas acrolein, the other metabolite of cyclophosphamide, has the ability to interfere with the antioxidant system, further causing the generation of strongly active oxygen-free radicals, superoxide radicals, and hydrogen peroxide [15]. These free radicals are implicated in several enzyme inhibitions, lipid peroxidation, as well as membrane injury [16]. The generation of free radicals mediates oxidative stress associated with cyclophosphamide treatment witnessed by the following pathways.

2.1.1. Mitochondrial-Dependent ROS Production

Cyclophosphamide (CP) treatment is responsible for the generation of a tremendous amount of ROS, which damages the inner membrane of the mitochondria, resulting in a reduced capacity of the myocardial cell mitochondria to neutralize the toxic effect of ROS. The toxic effect of CP treatment is associated with a reduction in oxidative phosphorylation in mitochondrial cristae, which causes a decrease in ATP production and contributes to further damage in mitochondria [17,18,19]. This is one of the prime reasons for altered cardiac physiology and contractility. The increased expression of the pro-apoptotic molecule BAX in the mitochondrial membrane by CP treatment is responsible for the induction of apoptosis. The cleavage of caspases, inhibition of protein kinase, and the activation of phosphatase and increased intracellular PH are responsible for the stimulation of BAX proteins. The ratio of proapoptotic and antiapoptotic molecules Bax and Bcl2 makes the mitochondrial pathway susceptible to apoptosis. The disturbance in calcium homeostasis is also responsible for the initiation of apoptotic cell death [20,21]. The interaction of ROS and calcium is bidirectional. The calcium ions increase the production of mitochondrial ROS by stimulating respiratory chain activity. The released ROS acts on the endoplasmic reticulum to generate more calcium and ROS. This leads to the opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, resulting in the release of pro-apoptotic factors [22,23].

2.1.2. Oxidative Stress Produced by NADPH

CP-intoxicated cardiomyocytes are responsible for increased synthesis of NADPH oxidase, NADH dehydrogenase, and NADPH oxidase. The activation of these enzymatic systems is associated with the generation of free radical-mediated oxidative stress [24,25]. The myocardial cell when exposed to CP treatment increases NADPH oxidase and other mediators of ROS. The oxidative stress generated by the NADPH-mediated pathway is responsible for the alteration of the Nrf2-HO/Nrf2-NQO-1 pathway, which causes damage in the myocardial cell [16,25,26].

2.2. Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline antibiotic that was first derived from a bacterium called Streptomyces peucetius in the early 1960s and was first used as a cytotoxic drug in 1969 [36,37]. It is a highly successful chemotherapeutic medication for solid tumors, soft-tissue sarcoma, breast cancer, Hodgkin’s disease, Kaposi’s sarcoma, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, pediatric leukemia, lung cancer, lymphomas, and various metastatic malignancies [2,38,39]. The drug’s utility is limited owing to its large number of side effects, such as the suppression of the hematopoietic system, gastrointestinal disturbances, and baldness, with cardiac damage being the most dangerous [40,41,42].

The advanced conditions of cancer patients treated with repeated doses of doxorubicin for more than a month developed severe symptoms of myocardial toxicity with a prevalent rate of more than 30%. The wide spread of symptoms ranged from ventricular failure, a decrease in QRS segment, cardiac dilatation, tachycardia (150 beats/min), and hypotension (blood pressure 70/50 mmHg) [43]. The patients were unresponsive to inotropic drugs and mechanical circulatory assist devices. Several biomarker levels such as creatine phosphokinase, serum glutamic-oxaloacetic transaminase, and lactate dehydrogenase were also elevated. The histopathological examination reported decreased myofibrils, altered structure of the sarcoplasmic reticulum, vacuolization of the cytoplasm, mitochondrial inflammation, and elevated numbers of lysosomes [44,45]. Different experimental animals such as rats, mice, and rabbits treated with doxorubicin also reported similar symptoms of myocardial toxicities. The experimental animals in several studies in a reproducible manner showed the symptoms of cardiomyopathy and heart failure with the exposure of doxorubicin [46,47].

Multiple processes are involved in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, which has been linked to increased myocardial damage due to oxidative free radicals, as well as lower levels of sulfhydryl groups and antioxidants. In addition to myofibrillar deterioration and intracellular calcium dysregulation, doxorubicin-induced cardiac toxicity is known to cause myofibrillar deterioration [48,49]. Mitochondrial biogenesis is also hypothesized to be actively involved in doxorubicin-mediated cardiac damage due to its potential to stimulate the cell death pathway while blocking topoisomerase 2β [50,51]. Alterations in gene expression of the cardiac system, such as the expression of muscle-specific genes (cardiac actin, myosin light chain, and muscle creatine kinase), are shown to decrease in response to doxorubicin exposure in acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity [52,53]. Endothelial dysfunction, an activated ubiquitin protease system, autophagy, and cell death collectively participate in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity, as do NO release, impaired adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels, iron regulatory protein (IRP) production, and augmented inflammatory mediator release [54,55].

2.2.1. Mechanism of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

Oxidative Stress

The generation of a tremendous amount of oxidative stress associated with DOX is the main culprit for the degeneration of myocardial cells. The imbalance between reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species, and the intrinsic antioxidant systems is responsible for the development of oxidative stress. The following are some of the important cellular mechanisms that are responsible for the development of this oxidative stress [56,57].

- A.

-

Altered mitochondrial functions

The mitochondria fulfill the huge oxygen demand of cardiomyocytes. DOX treatment is responsible for structural changes in the mitochondria responsible for the depletion of energy production in the form of ATP [58,59].

The inner membrane of mitochondria contains an important component—cardiolipin. The interaction between cardiolipin and DOX is one of the major events responsible for cardiotoxicity associated with DOX. DOX and cardiolipin bind irreversibly due to the cationic charge of DOX and the anionic charge of cardiolipin, resulting in the accumulation of DOX in mitochondria. Cardiolipin has a major role in electron transport, but due to the formation of a complex with DOX, the activation of several enzymes is inhibited, resulting in an altered electron transport chain. Apart from this, DOX-mediated oxidative phosphorylation also plays an important role in the events of myocardial toxicity [60,61].

- B.

-

Fe–Dox complex

The hydroxy and ketone groups of DOX interact with Ferric ion (Fe3+) and form a complex. This complex interacts with the cell membrane and causes lipid peroxidation and generates free radicals. DOX is responsible for the accumulation of iron in mitochondria and initiates the event of apoptosis in the myocardial cell. DOX treatment is responsible for the inactivation of iron regulatory protein IRP1, and IRP2 and iron are transported into mitochondria by transport protein Mitoferrin-2. DOX causes the alteration of the post-translational modification of IRP1 and the recognition of iron-responsive elements is lost and results in altered iron homeostasis [62,63].

- C.

-

Role of NADPH in the generation of ROS

The catalytic activities of the enzymes nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) and mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase are responsible for the generation of free radicals. Angiotensin II is responsible for the elevation of NADPH oxidase and having a pivotal role in the generation of free radicals. DOX treatment is associated with the incremental genesis of nitric oxide synthase; nitric oxide reductase and P450 reductase enzymes contribute to the development of oxidative stress in the myocardial cell due to the formation of reactive oxygen species [64,65].

- D.

-

Generation of reactive oxygen species by nitric oxide

DOX treatment is responsible for the increased synthesis of nitric oxide mediated by the enzymes neuronal NO synthase, inducible NO synthase, and endothelial NO synthase. Nitric oxide is found in increased levels in damaged myocardial tissues. Nitric oxide by lipid peroxidation from peroxynitrite is responsible for the development of oxidative stress in mitochondria, resulting in necrosis and apoptosis [66,67].

- E.

-

Generation of oxidative stress by nrf2

The depletion of Nrf2 protein in DOX treatment is responsible for associated myocardial toxicities. The expression of Nrf2 is responsible for the induction of autophagy and maintains homeostasis between autophagy and oxidative stress [68].

Apoptosis

Through both the intrinsic and extrinsic pathways, DOX stimulates the apoptosis of the cardiac muscle cells. DOX toxicity results in an imbalance in various factors including an increase in oxidative stress, which activates HSF-1 (heat shock factor 1), thereby inducing HSP-25 (heat shock protein), and subsequently, p53 is equalized, leading to the production of proapoptotic factors such as Fas, FasL, and c-Myc, which is responsible for cardiac muscle cell death [69,70]. Another factor responsible for the cardiotoxicity associated with DOX is DOX-induced cardiotoxicity leading to the depletion of transcriptional factor GATA-4, which is responsible for regulating the apoptotic pathway via activating the anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-XL. In addition, DOX-induced cardiotoxicity is also found to increase active glycogen synthase kinase 3β (GSK3β), which is a negative regulator of GATA-4 in the nucleus [71]. Similarly, a role of TLR-2 (Toll-like receptor-2)-mediated cytokine production, cardiac dysfunction, and apoptosis by the activation of the pro-inflammatory nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway has been observed to be involved in DOX-induced cardiotoxicity [39]. Some studies showed that DOX-treated murine hearts inhibit Protein Kinase B (PKB/AKT), which is involved in the regulation of cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism. AKT is also found to play a critical role in decreasing oxidative stress via deactivating (GSK3β), which thereby decreases FYN nuclear translocation-mediated NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) nuclear export and degradation [72,73].

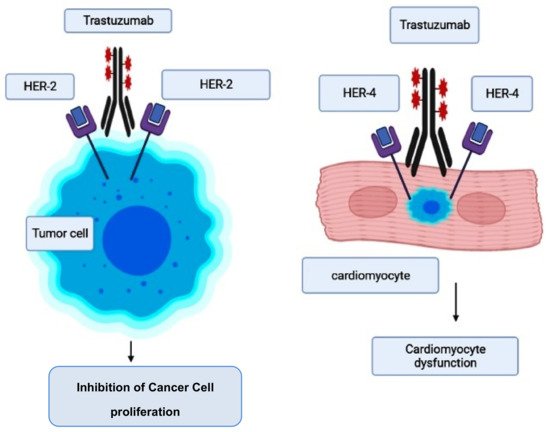

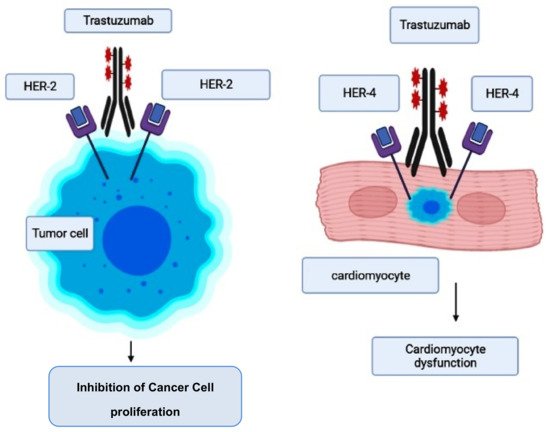

2.3. Trastuzumab-Induced Cardiotoxicity

This is a monoclonal antibody that is employed for the treatment of breast cancer patients who concurrently have an elevated human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2, also known as ErbB-21) level [88]. While therapeutic therapy with trastuzumab is reported to reduce morbidity and mortality in breast cancer patients, there are serious cardiac adverse effects that need to be checked [89,90]. HER2 is an important target for breast cancer and, similarly, a prime target for trastuzumab [91]. However, some mutant mouse models have documented that there are also some important roles regulated by ErbB-2 genes, such as in postnatal cardiomyocyte function and development [92]. Similarly, evidence suggests that ErbB-2 genes are involved in the normal functioning of the myocardium, which includes the involvement of a number of key pathways (such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase, mitogen-activated protein kinase, and focal adhesion kinase) that are required for cardiomyocyte maintenance, and the inhibition of apoptosis. Therefore, the blockade of ErbB signaling by trastuzumab could have been a major reason for its ability to induce cardiotoxicity [93,94].

However, the risk of developing trastuzumab cardiotoxicity has been seen to increase in patients who receive concurrent anthracycline therapy [90,95,96]. When trastuzumab suppresses ErbB2 signaling, it was reported that it further accelerates the anthracycline’s ability to induce sarcomeric protein breakdown, increasing the chances of cardiac toxicity and heart failure [97]. The pathogenesis and molecular mechanism involved in trastuzumab-induced cardiotoxicity are given in Figure 2 [98].

Figure 2. Mode of action of trastuzumab and its cardiotoxicity induction.

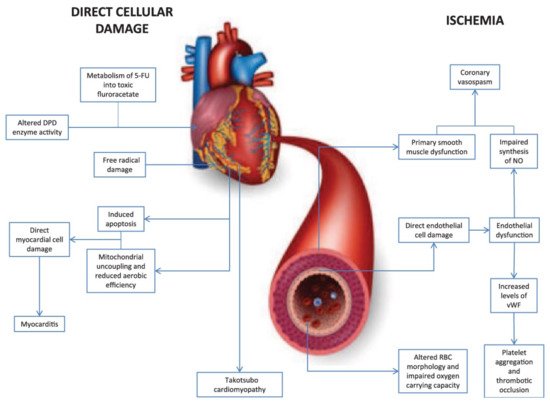

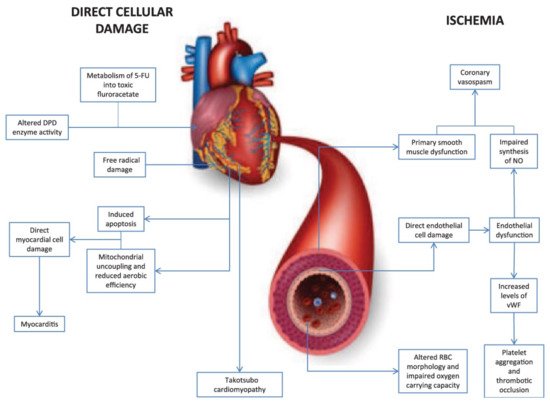

2.4. Fluorouracil-Induced Cardiotoxicity

5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a pyrimidine analogue chemotherapy medication employed in the treatment of a number of cancer types, including colorectal, breast, gastric, pancreatic, prostate, and bladder cancers, among others [99,100]. Myelosuppression, diarrhea, stomatitis, nausea, vomiting, and baldness are common side effects of the medication. Furthermore, 5-FU has been linked to cardiotoxicity, which includes myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias, altered blood pressure, left ventricular failure, cardiac arrest, and sudden death [99]. The potential mechanisms involved in 5-FU-induced cardiotoxicity are given in Figure 3 [101]. Angina is noticeable mostly during infusions, and occasionally it is delayed until a few hours after 5-FU application. The incidence of angina associated with the use of 5-FU ranges from 1.2 to 18 percent [102,103,104,105]. Cardiotoxicity that is severe or life-threatening or ventricular arrhythmias, on the other hand, are far less common, with an incidence of about 0.55 percent [106]. When compared to anthracyclines, cardiac adverse effects of 5-FU are rare, with an incidence of 1.2–7.6%, and life-threatening cardiotoxicity of 5-FU has been documented in less than 1% of cases [107]. Though the exact processes of 5-FU-mediated cardiac toxicity are yet unknown, spasm of the coronary artery is suggested as a hypothesis [64]. Ultrasound and angiography have been used in several investigations to show that 5-FU infusion causes both coronary and brachial artery vasospasm. Patients with coronary vasospasm may have ECG findings suggestive of coronary occlusion, such as ST-segment elevation and biochemical changes in myocardial injury with increased troponin. As a result, it is recommended that when 5-FU is given to cancer patients, a high index of suspicion for probable cardiac toxicity be maintained [108].

Figure 3. Diagrammatic representation of two major mechanisms of 5-fluorouracil-induced cardiotoxicity.

2.5. Cisplatin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

Cisplatin, commonly known as cis-di ammine dichloroplatinum (CDDP), is a highly effective chemotherapy drug [109]. In diseases such as ovarian and cervical cancer and testicular cancer, it is used alone or in combination regimens [110]. However, due to adverse effects, including toxicities to the kidney, liver, and gastrointestinal disturbances, cisplatin’s clinical use is restricted. Despite these side effects, many survivors of cisplatin treatment may develop acute or chronic cardiovascular problems, which can negatively impact their quality of life [111]. CDDP-induced cardiotoxicity has been linked to ventricular and supraventricular arrhythmias, occasional sinus bradycardia, alterations in electrocardiography, occasional total atrioventricular block, and congestive heart failure. With cisplatin-based chemotherapy, oxidative stress is considered as a major reason for cardiac toxicity [112]. It has also been shown that cisplatin-based chemotherapy causes a decrease in the concentration of different antioxidants in patients. It may also cause ROS generation by accumulating in mitochondria [113]. However, it has been documented that all of these factors collectively lead to congestive heart failure and sudden cardiac death. Table 1 summarizes the adverse cardiotoxic consequences of chemotherapy [114].

Table 1. Different types of cardiotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents.

| Drugs Causing Ischemia or Thromboembolism | Cisplatin, Thalidomide, Fluorouracil, Capecitabine, Paclitaxel, Docetaxel, Trastuzumab, Anthracyclines/Anthraquinones, Cyclophosphamide |

|---|---|

| Drugs that Cause Hypertension | bevacizumab, cisplatin, sunitinib, sorafenib |

| Tamponade and Endomyocardial Fibrosis | busulfan |

| Autonomic Neuropathy | vincristine |

| Bradyarrhythmias | paclitaxel |

| Myocarditis with Hemorrhage (rare) | cyclophosphamide (high-dose therapy) |

| Pulmonary Fibrosis | bleomycin, methotrexate, busulfan, cyclophosphamide |

| Raynaud’s Phenomenon | vinblastine, bleomycin |

| Torsades de Pointes or QT Prolongation | arsenic trioxide |

2.6. Immunotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity

With cancer progression, initially, the body’s immune system prevents tumor outgrowth. However, cancer cells can escape the various pathways that provide immunologic antitumor responses, and such pathways include immune system inhibitory pathways such as cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) (natural checkpoints that dampen the antitumor responses of T cells). Therefore, various studies were carried out to determine if by stimulating an antitumor immune response in cancer patients, cancer could be fought better. Since then, immunotherapy came into existence, and this is divided into passive immunotherapies such as monoclonal antibodies, checkpoint inhibitors, cytokine therapy, bispecific T cell engager and antitumor vaccines or adoptive T cell transfer, which dramatically improved outcomes for wide varieties of cancer, among which adoptive T cell therapy and immune checkpoint inhibitors are most widely used and are used as longer duration therapy. However, having the benefit of activated immune response came with a price, as both the therapies have been reported to cause various cardiovascular complications such as hypotension, arrhythmia, left ventricular dysfunction, myocarditis, with clinical presentations ranging from asymptomatic cardiac biomarker elevation to heart failure, and cardiogenic shock [115,116,117,118,119].

2.6.1. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors and Cardiac Complications

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) show their action by amplifying T cell-mediated immune response against cancer cells, by blocking the intrinsic down-regulators of immunity, such as programmed cell death 1 (PD-1), programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4). These immune checkpoint inhibitors can induce tumor responses in different types of tumors including non-small cell lung cancer, renal cancer, melanoma, and Hodgkin’s disease. Although ICIs have brought improvement in the treatment of many aggressive malignancies, several studies have reported that PD-1 deletion and CTLA-4 inhibition can cause serious cardiac complications. When an experiment was carried out in a mouse model, it was reported that with the loss of the PD-1 or CTLA-4 receptor, significant infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells took place, resulting in the development of a dilated cardiomyopathy. However, the exact mechanism underlying cardiac toxicity associated with checkpoint inhibitors has not been studied comprehensively, and immune-mediated myocarditis could also be the exaggerated adaptive immune response against shared epitopes in the myocardium and tumor cells [120,121,122,123,124].

2.6.2. CDK4/6 Inhibitors

Cyclins have a major role to play in regulating the cell cycle. They show their activity by interacting with their partner serine/threonine CDKs (cyclin-dependent kinases). There are different types of CDKs available. CDKs 1–6 have a major role in coordinating cell cycle progression, whereas CDKs 7, 8, and 9 show downstream effects as transcriptional regulators. Among all the CDKs, the major target in cancer therapy is CDK 4/6, since it is required for the initiation and progression of various malignancies and is usually hyperactive in cancers [125,126]. CDKs generally help in regulating the cellular transition from G1 phase to S1 phase in the cell cycle, and the inhibitors (CDK 4/6 inhibitors) show their action by blocking the proliferation of cancer cells by effectively inducing G1 cell cycle arrest. However, CDK inhibitors have been seen to cause cardiac complications. One major concern about the use of CDK inhibitors is that they have been seen to potentially increase the QTc interval, which is most commonly seen with ribociclib. Some studies showed that ribociclib is capable of down-regulating the expression of KCNH2 (which encodes for the potassium channel Herg) and up-regulating the expression of SCN5A and SNTA1 (which encode for the sodium channels syntrophin-α1 and Nav1.5), which are the genes associated with long QT syndrome. There is also evidence that shows the increasing risk of thromboembolic events with the use of CDK inhibitors. However, there are limited data available regarding the cardiac safety of CDK 4/6 inhibitors. Therefore, it requires detailed investigation to understand the exact mechanism [127,128].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ph14100970

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!