“Pseudoneglect” refers to a spatial processing asymmetry consisting of a slight but systematic bias toward the left shown by healthy participants across tasks. It has been attributed to spatial information being processed more accurately in the left than in the right visual field. Importantly, evidence indicates that this basic spatial phenomenon is modulated by emotional processing, although the presence and direction of the effect are unclear.

- emotion

- perceptual asymmetries

- lateralization

- visual neglect

- attention bias

1. Introduction

Over the last two decades, much research has focused on the influence of emotion on spatial biases in both patients and neurologically intact individuals, based on the strong influence that emotion has on attention in everyday life, on the tight interconnection between the neural mechanisms that mediate these two phenomena, and on the brain lateralization of emotion processing. In this context, spatial attention tasks such as the line bisection have been used in an attempt to disentangle the issue of emotion and attention lateralization. The rationale is that if attention is right-lateralized and emotion is also right-lateralized (i.e., “right-hemisphere hypothesis” [1]), then both functions concur in shifting the activation balance in favor of the right hemisphere, enhancing the pseudoneglect in the left hemifield. An alternative account sees positive emotion lateralized to the left and negative emotion to the right (i.e., the “valence-specific hypothesis” [2]) predicts that negative emotion should increase the relative activation of the right hemisphere and enhance pseudoneglect. In contrast, positive emotion should increase the relative activation of the left hemisphere and attenuate pseudoneglect.

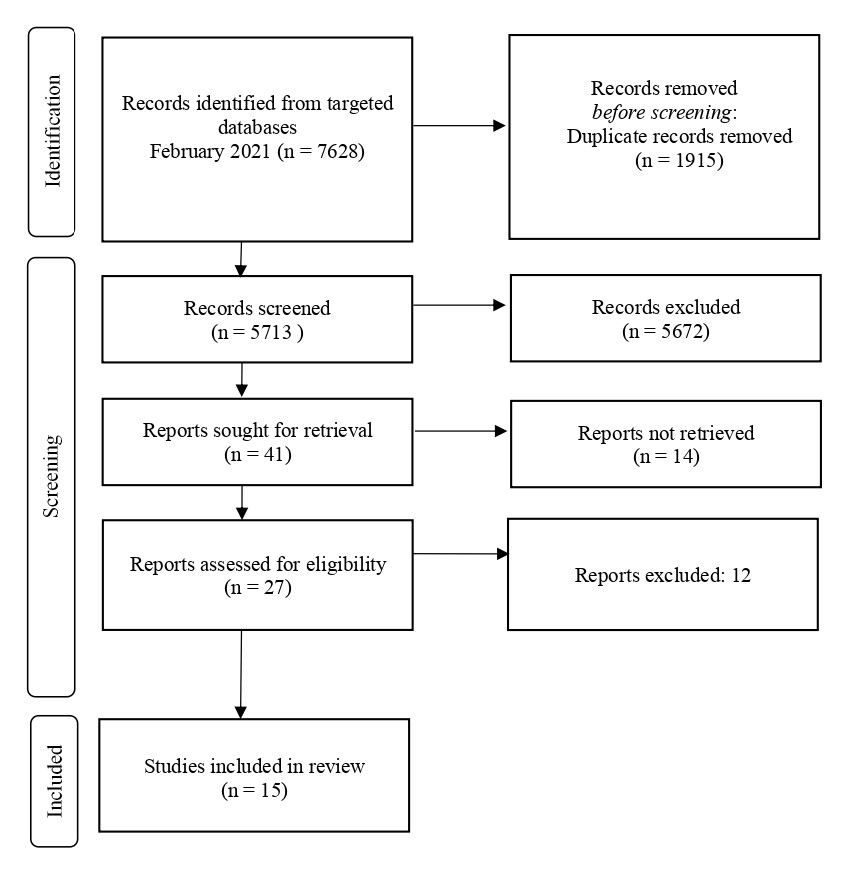

The association between emotion and the right hemisphere goes back to the very early neurology literature when Mills [3] observed that patients with a lesion in the right side of the brain had an impairment in emotional expression. For the right-hemisphere hypothesis, the perception of emotional stimuli is related to the activity of the right hemisphere, regardless of affective valence [4]. Conversely, the valence-specific hypothesis is based on evidence that lesions in the left frontal lobe were related to negative emotional states while lesions in the right hemisphere were more associated with positive or maniac emotional states [5]. For the valence-specific hypothesis, the left hemisphere processes positive emotions, whereas the right hemisphere processes negative emotions [6]. An alternative, the “approach–withdrawal” hypothesis, proposes that brain asymmetries observed for positive and negative emotions are related to the underlying motivational system linked to positive and negative emotions [7]. Accordingly, the left prefrontal cortex is involved in processing approach-related emotions, such as happiness and anger, whereas the right prefrontal cortex processes withdrawal-related emotions, such as sadness and fear. Despite a large body of research, evidence on the interaction between emotion and spatial attention is still not well understood. A systematic review on the relation between pseudoneglect and emotion conducted according to the PRISMA guidelines (see Figure 1), [8] yielded 15 studies published by February 2021 that measured the relationship between emotional processing and spatial attention pseudoneglect.

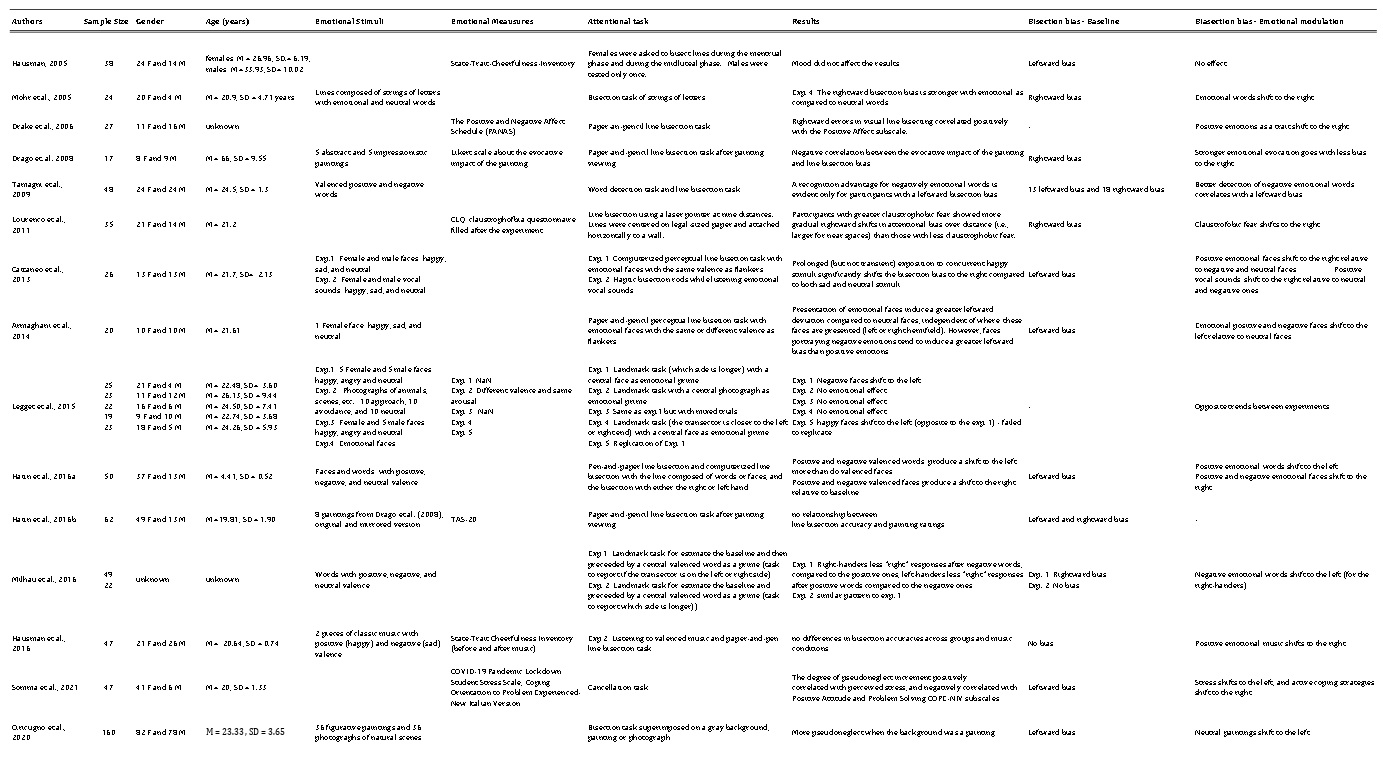

Inclusion criteria were: (1) original, peer-reviewed articles; (2) written in English; (3) conducted on adults; (4) included at least one task to measure pseudoneglect (line bisection task, landmark task, greyscales task, grating scales task, tactile rod bisection task, lateralized visual detection, cancellation task; and (5) included at least one task with emotional stimuli or employed a measure of emotional state/trait as they relate to pseudoneglect. Articles from all publication years were accepted (see Table 1).

2. Current Findings and Conclusions

Of the 15 studies meeting the inclusion criteria, 11 studies used visual stimuli, such as faces, words, and pictures with emotional connotations. The main finding is that the majority of the studies found that pseudoneglect was modulated by emotional stimuli or by participants’ self-reported emotional state or trait. However, the direction of these effects is less clear-cut. Of the studies with emotional faces or words, three reported that emotion induces a rightward bias (or attenuates the leftward bias): one study used emotional words [9], one used angry and happy faces [10], and one used happy and sad faces [11]. Four studies reported that emotion induces a leftward bias (or attenuates the rightward bias): one study used happy and sad faces [11] and three studies used negative words [9][12][13][14]. One study with faces and words reported mixed results [15]. The two studies using auditory stimuli [11][16] report a rightward bias when listening to sad and happy music. Moreover, studies on the effects of self-reported affect and traits on pseudoneglect show that positive affect [17] and positive attitude [18] are correlated with a rightward bias. Finally, greater self-reported claustrophobic fear is related to a rightward bias when the line bisection is performed at a short distance [19].

The entry conclude that there are substantial methodological differences across studies that could account for the heterogeneity in the observed findings. Firstly, the time between presenting the emotional stimuli and spatial attention tasks varies, with some employing simultaneous and others sequential presentation. This difference does not rule out low-level variables (such as surround suppression) due to simultaneous versus sequential stimulus presentation that might contribute to the attention bias [20]. Secondly, some studies present the line flanked by two emotional stimuli and some others flanked by just one stimulus on the left or right side of the line. However, contextual stimuli may influence the localization of the subjective midpoint, biasing the bisection away from the location of the flanker [21]. Indeed, using one flanker seems to increase the attentional load for extracting the segment from the background and reduce the salience of the flanked-line segment [22]. Thirdly, there are individual differences in the attention bias at baseline and this variability does not seem to predict the direction of changes driven by the emotional modulation of the bisection bias. Finally, an additional neural factor may contribute to the complex picture that emerges from the literature. This is related to which hemisphere is preferentially involved in processing the specific category (e.g., faces, words, sounds, etc.) of the stimuli used and their relative position in the visual field (i.e., central vs. peripheral presentation). For instance, visual stimuli such as faces and words likely activate networks of non-parietal visual category-selective regions that include the right fusiform face area [23] and the left visual word form area [24].

Future studies should consider comparing brain activation asymmetries during the baseline and during the task while taking into account the brain hemisphere that is preferentially involved in processing the category of stimuli used.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/sym13081531

References

- Borod, J. C., Cicero, B. A., Obler, L. K., Welkowitz, J., Erhan, H. M., Santschi, C., ... & Whalen, J. R.; Right hemisphere emotional perception: evidence across multiple channels. Neuropsychology 1998, 12(3), 446, DOI: 10.1037//0894-4105.12.3.446.

- Martin Kronbichler; Florian Hutzler; Heinz Wimmer; Alois Mair; Wolfgang Staffen; Gunther Ladurner; The visual word form area and the frequency with which words are encountered: evidence from a parametric fMRI study. NeuroImage 2004, 21, 946-953, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.021.

- Mills, C.K.; The cerebral mechanisms of emotional expression. Transactions of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia 1912, 34, 381-389, https://doi.org/10.1037/0894-4105.7.4.445.

- Guido Gainotti; Studies on the Functional Organization of the Minor Hemisphere. International Journal of Mental Health 1972, 1, 78-82, 10.1080/00207411.1972.11448587.

- Edward K. Silberman; Herbert Weingartner; Hemispheric lateralization of functions related to emotion. Brain and Cognition 1986, 5, 322-353, 10.1016/0278-2626(86)90035-7.

- Danny Wedding; Loretta Stalans; Hemispheric Differences in the Perception of Positive and Negative Faces. International Journal of Neuroscience 1985, 27, 277-281, 10.3109/00207458509149773.

- Richard J. Davidson; Anterior cerebral asymmetry and the nature of emotion. Brain and Cognition 1992, 20, 125-151, 10.1016/0278-2626(92)90065-t.

- Joanne E McKenzie; Sarah E Hetrick; Matthew J Page; Updated reporting guidance for systematic reviews: Introducing PRISMA 2020 to readers of the Journal of Affective Disorders. Journal of Affective Disorders 2021, 292, 56-57, 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.035.

- C. Mohr; U. Leonards; Rightward bisection errors for letter lines: The role of semantic information. Neuropsychologia 2007, 45, 295-304, 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.07.003.

- Hatin, B., & Sykes Tottenham, L; What's in a line? Verbal, facial, and emotional influences on the line bisection task. Brain and Cognition 2016, 21(4-6), 689-708, .

- Zaira Cattaneo; Carlotta Lega; Jana Boehringer; Marcello Gallucci; Luisa Girelli; Claus-Christian Carbon; Happiness takes you right: The effect of emotional stimuli on line bisection. Cognition and Emotion 2013, 28, 325-344, 10.1080/02699931.2013.824871.

- Sheyan J. Armaghani; Gregory P. Crucian; Kenneth M. Heilman; The influence of emotional faces on the spatial allocation of attention. Brain and Cognition 2014, 91, 108-112, 10.1016/j.bandc.2014.09.006.

- Audrey Milhau; Thibaut Brouillet; Vincent Dru; Yann Coello; Denis Brouillet; Valence activates motor fluency simulation and biases perceptual judgment. Psychological Research 2016, 81, 795-805, 10.1007/s00426-016-0788-8.

- C. Tamagni; T. Mantei; P. Brugger; Emotion and space: lateralized emotional word detection depends on line bisection bias. Neuroscience 2009, 162, 1101-1105, 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.05.072.

- Nathan Leggett; Nicole Thomas; Michael Nicholls; End of the line: Line bisection, an unreliable measure of approach and avoidance motivation. Cognition and Emotion 2015, 30, 1164-1179, 10.1080/02699931.2015.1053842.

- Markus Hausmann; Sophie Hodgetts; Tuomas Eerola; Music-induced changes in functional cerebral asymmetries. Brain and Cognition 2016, 104, 58-71, 10.1016/j.bandc.2016.03.001.

- Roger Drake; Lisa Myers; Visual attention, emotion, and action tendency: Feeling active or passive. Cognition and Emotion 2006, 20, 608-622, 10.1080/02699930500368105.

- Federica Somma; Paolo Bartolomeo; Federica Vallone; Antonietta Argiuolo; Antonio Cerrato; Orazio Miglino; Laura Mandolesi; Maria Clelia Zurlo; Onofrio Gigliotta; Further to the Left: Stress-Induced Increase of Spatial Pseudoneglect During the COVID-19 Lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 573846, 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.573846.

- Stella F. Lourenco; Matthew Longo; Thanujeni Pathman; Near space and its relation to claustrophobic fear. Cognition 2011, 119, 448-453, 10.1016/j.cognition.2011.02.009.

- Sabine Kastner; Peter De Weerd; Robert Desimone; Leslie G. Ungerleider; Mechanisms of Directed Attention in the Human Extrastriate Cortex as Revealed by Functional MRI. Science 1998, 282, 108-111, 10.1126/science.282.5386.108.

- Sergio Chieffi; Mariateresa Ricci; INFLUENCE OF CONTEXTUAL STIMULI ON LINE BISECTION. Perceptual and Motor Skills 2002, 95, 868-874, 10.2466/pms.95.7.868-874.

- Sergio Chieffi; Alessandro Iavarone; Andrea Viggiano; Marcellino Monda; Sergio Carlomagno; Effect of a visual distractor on line bisection. Experimental Brain Research 2012, 219, 489-498, 10.1007/s00221-012-3106-8.

- Nancy Kanwisher; Galit Yovel; The fusiform face area: a cortical region specialized for the perception of faces. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2006, 361, 2109-2128, 10.1098/rstb.2006.1934.

- Martin Kronbichler; Florian Hutzler; Heinz Wimmer; Alois Mair; Wolfgang Staffen; Gunther Ladurner; The visual word form area and the frequency with which words are encountered: evidence from a parametric fMRI study. NeuroImage 2004, 21, 946-953, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.10.021.