Synovial sarcoma (SS) is a rare and highly malignant tumor and a type of soft tissue sarcoma (STS), for which survival has not improved significantly in recent years. Synovial sarcomas occur mostly in adolescents and young adults (15–35 years old), usually affecting the deep soft tissues near the large joints of the extremities, with males being at a slightly higher risk. Despite its name, synovial sarcoma is neither related to the synovial tissues that are a part of the joints, i.e., the synovium, nor does it express synovial markers; however, the periarticular synovial sarcomas can spread as a secondary tumor to the joint capsule. SS was initially described as a biphasic neoplasm comprising of both epithelial and uniform spindle cell components. Synovial sarcoma is characterized by the presence of the pathognomonic t (X; 18) (p11.2; q11.2) translocation, involving a fusion of the SS18 (formerly SYT) gene on chromosome 18 to one of the synovial sarcoma X (SSX) genes on chromosome X (usually SSX1 or SSX2), which is seen in more than 90% of SSs and results in the formation of SS18-SSX fusion oncogenes.

- synovial sarcoma

- imaging diagnosis

- immunophenotyping

1. Introduction

2. Diagnosis

2.1. Clinical Presentation

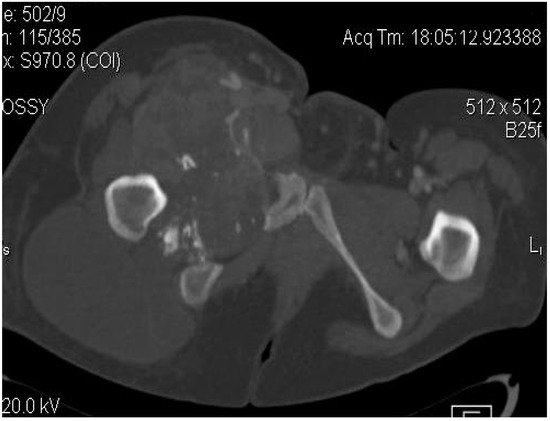

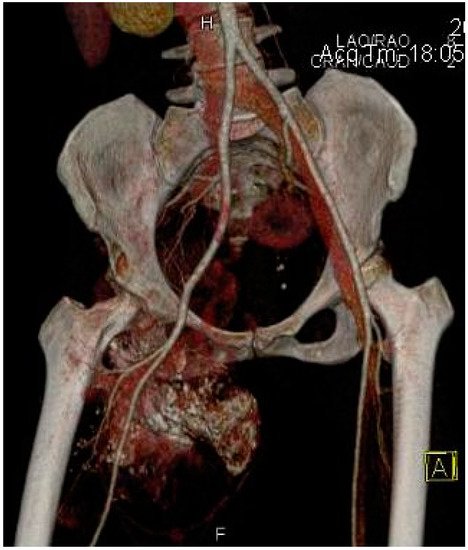

2.2. Imaging Examinations

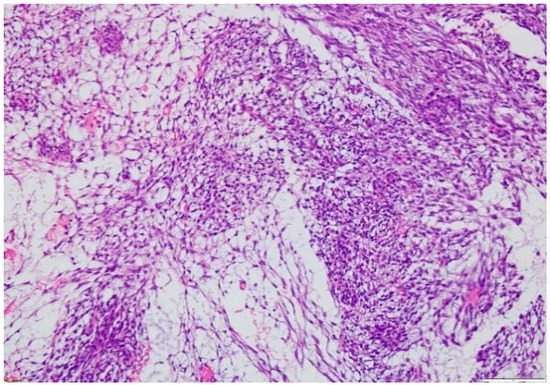

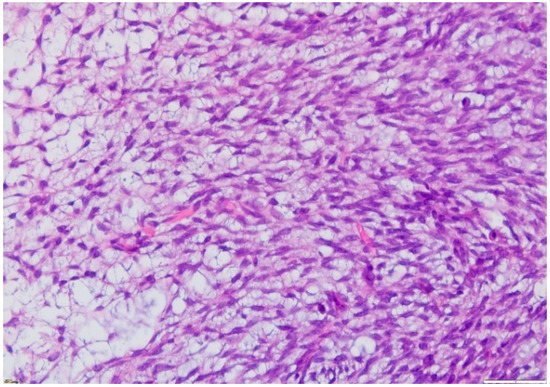

2.3. Biopsy

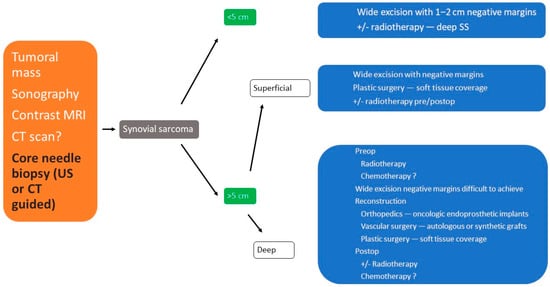

3. Treatment

3.1. Surgical Treatment

3.2. Radiotherapy

3.3. Chemotherapy

3.4. Other Therapeutical Options

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/app11167407

References

- Kransdorf, M.J. Malignant soft-tissue tumors in a large referral population: Distribution of diagnoses by age, sex, and location. AJR Am. J. Roentgenol. 1995, 164, 129–134.

- Sistla, R.; Tameem, A.; Vidyasagar, J.V. Intra articular synovial sarcoma. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2010, 53, 115–116.

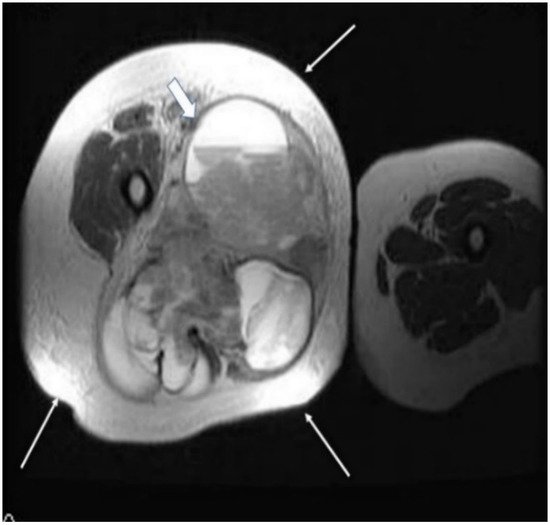

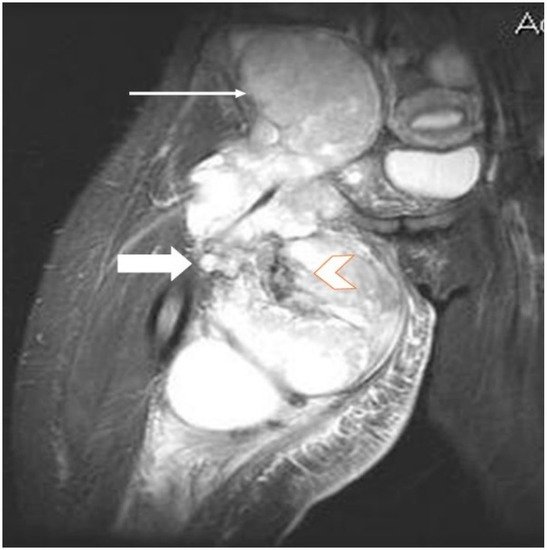

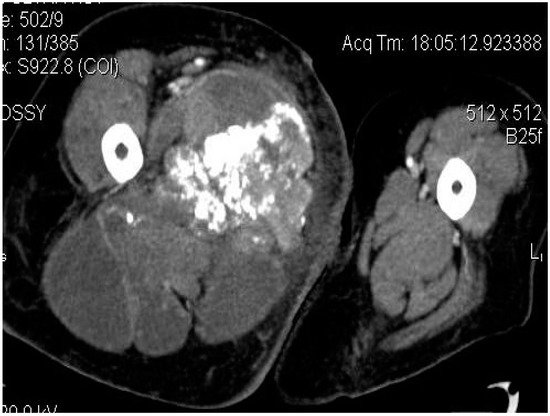

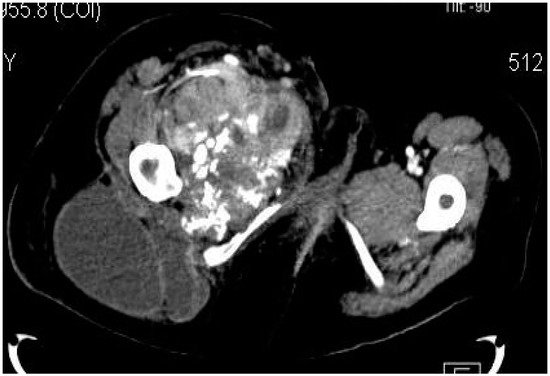

- Murphey, M.D.; Gibson, M.S.; Jennings, B.T.; Crespo-Rodríguez, A.M.; Fanburg-Smith, J.; Gajewski, D.A. Imaging of Synovial Sarcoma with Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. RadioGraphics 2006, 26, 1543–1565.

- Joseph, N.; Laurent, S.; Zheng, S.; Stirnadel-Farrant, H.; Dharmani, C. Epidemiology of synovial sarcoma in EU28 countries. Sarcoma 2019, 30, 706–707.

- Smith, M.; Fisher, C.; Wilkinson, L.; Edwards, J. Synovial sarcomas lack synovial differentiation. Histopathology 1995, 26, 279–281.

- Thway, K.; Fisher, C. Synovial sarcoma: Defining features and diagnostic evolution. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 18, 369–380.

- Ryan, C.W.; Meyer, J. Clinical Presentation, Histopathology, Diagnostic Evaluation, and Staging of Soft Tissue Sarcoma. UpToDate. January 2015. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/clinical-presentation-histopathology-diagnostic-evaluation-and-staging-of-soft-tissue-sarcoma (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Folpe, A.L.; Schmidt, R.A.; Chapman, D.; Gown, A.M. Poorly Differentiated Synovial Sarcoma: Immunohistochemical Distinction From Primitive Neuroectodermal Tumors and High-Grade Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998, 22, 673–682.

- Siegel, H.J.; Sessions, W.; Casillas, M.A., Jr.; Said-Al-Naief, N.; Lander, P.H.; Lopez-Ben, R. Synovial sarcoma: Clinicopathologic features, treatment, and prognosis. Orthopedics 2007, 30, 1020–1025.

- Robbins, P.F.; Morgan, R.A.; Feldman, S.A.; Yang, J.C.; Sherry, R.M.; Dudley, M.E.; Wunderlich, J.R.; Nahvi, A.V.; Helman, L.J.; Mackall, C.L.; et al. Tumor Regression in Patients with Metastatic Synovial Cell Sarcoma and Melanoma Using Genetically Engineered Lymphocytes Reactive With NY-ESO-1. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 917–924.

- Vargas, B. Synovial Cell Sarcoma. Medscape Ref. 2014. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1257131-overview (accessed on 1 November 2020).

- Palmerini, E.; Paioli, A.; Ferrari, S. Emerging therapeutic targets for synovial sarcoma. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2014, 14, 791–806.

- Jo, V.Y.; Fletcher, C.D. WHO classification of soft tissue tumors: An update based on the 2013 (4th) edition. Pathology 2014, 46, 95–140.

- Song, S.; Park, J.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, I.H.; Han, I.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, S. Effects of Adjuvant Radiotherapy in Patients with Synovial Sarcoma. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 40, 306–311.

- Nakamura, T.; Saito, Y.; Tsuchiya, K.; Miyachi, M.; Iwata, S.; Sudo, A.; Kawai, A. Is perioperative chemotherapy recommended in childhood and adolescent patients with synovial sarcoma? A systematic review. Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 51, 927–931.

- Casali, P.G.; Picci, P. Adjuvant chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2005, 17, 361–365.

- Chao, C.; Al-Saleem, T.; Brooks, J.J.; Kraybill, W.G.; Eisenberg, B. Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Soft Tissue Sarcomas: Tumor Expression Correlates With Grade. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2001, 8, 260–267.

- Martín-Liberal, J.; Pousa, A.L.; Martin-Broto, J.; Cubedo, R.; Gallego, O.; Brendel, E.; Tirado, O.M.; Del Muro, X.G. Phase I trial of sorafenib in combination with ifosfamide in patients with advanced sarcoma: A Spanish group for research on sarcomas (GEIS) study. Investig. New Drugs 2014, 32, 287–294.

- D’Angelo, S.P.; Melchiori, L.; Merchant, M.S.; Bernstein, D.; Glod, J.; Kaplan, R.; Grupp, S.; Tap, W.D.; Chagin, K.; Binder, G.K.; et al. Antitumor Activity Associated with Prolonged Persistence of Adoptively Transferred NY-ESO-1 c259T Cells in Synovial Sarcoma. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 944–957.