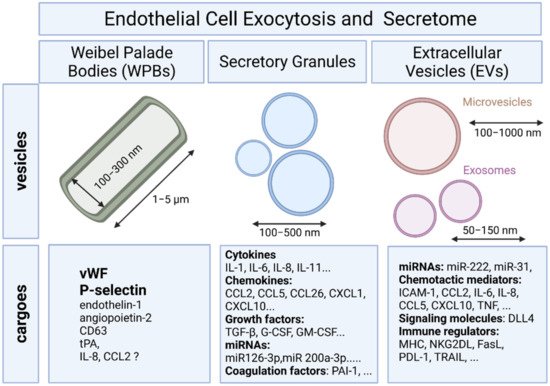

As a cellular interface between the blood and tissues, the endothelial cell (EC) monolayer is involved in the control of key functions including vascular tone, permeability and homeostasis, leucocyte trafficking and hemostasis. EC regulatory functions require long-distance communications between ECs, circulating hematopoietic cells and other vascular cells for efficient adjusting thrombosis, angiogenesis, inflammation, infection and immunity. This intercellular crosstalk operates through the extracellular space and is orchestrated in part by the secretory pathway and the exocytosis of Weibel Palade Bodies (WPBs), secretory granules and extracellular vesicles (EVs).

- endothelial cells

- intercellular communication

- tunneling nanotubes

- exosomes

- extracellular vesicles

- secretome

- cytokines

- chemokines

- ectodomain shedding

- secretory pathway

1. Introduction

Lining all blood vessels of the vascular tree, the endothelium represents a surface area of around 5000 m2 composed of roughly 1014 endothelial cells (ECs) and can be perceived as an organ system [1]. At the interface between the blood and tissues, the EC layer is involved in the control of key functions including vascular tone, permeability and homeostasis, leucocyte trafficking and hemostasis [2][3].

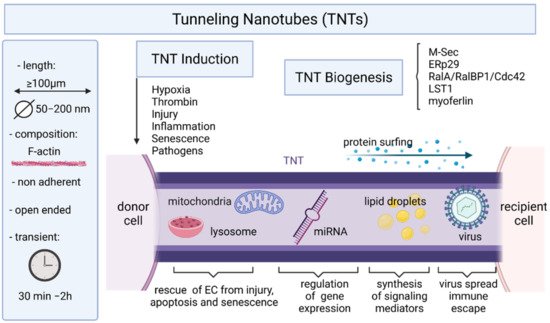

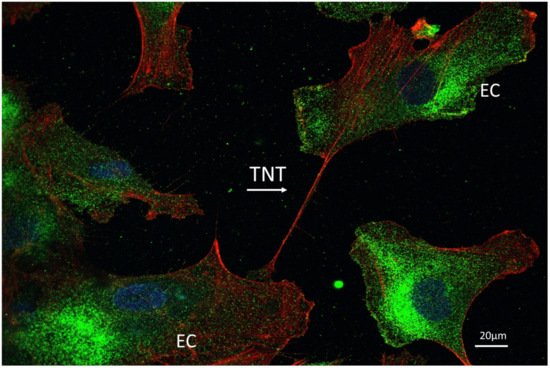

Intercellular communication is a fundamental process in the development and functioning of multicellular organisms and to operate effective mobilization and recruitment of circulating cells at sites of inflammation, infection, or injury. An intensive crosstalk between ECs and circulating hematopoietic cells and other vascular cells is needed to maintain vessel structure, function and homeostasis. Major mechanisms governing EC interaction with adjacent cells in tissue or blood vessels include exocytosis and direct transfer of small cytoplasmic components via gap junction [4][5]. For communication with more distant cells, ECs must use additive mechanisms to counteract the diluting effect mediated by the constant flow of blood. To achieve long-distance communications, several strategies can be used, including the secretion of messengers such as cytokines, chemokines, complement proteins, coagulation or growth factors, the release of extracellular vesicles (EVs), or the formation of thin tubular membranous channels termed tunneling nanotubes (TNTs), which may contain and transfer different biomolecules (e.g., signaling mediators, proteins, lipids, and RNAs) or pathogens.

2. Endothelial Exocytosis

2.1. Secretory Pathway and Weibel–Palade Bodies

To provide a rapid answer to external stimulation or stress, ECs are equipped with specific rod-shaped organelles known as Weibel–Palade bodies (WPBs) in which several bioactive molecules are stored and rapidly released upon stimulation (Figure 1).

2.2. Endothelial Exocytosis of Secretory Granules

Differential release of various granule populations is a well-known feature of certain regulated secretory cells and it has been described for ECs. Stimulus-release coupling occurs via regulated exocytosis of secretory vesicles and Ca2+ was a key trigger of this process [12]. The N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor (NSF) protein is a key player in the multiple steps of both the constitutive secretory and endocytic pathways acting in ER to Golgi transport and in endocytic vesicle fusion [13]. Cytokines, chemokines, enzymes, growth factors, matrix proteins, and signaling molecules can all be secreted by fusion of the secretory granule with the plasma membrane and the subsequent release of the vesicular contents (Figure 1) [12].

Cytokines and other soluble mediators can be involved in distant as well as local communication. ECs secrete a range of paracrine, autocrine, and endocrine factors that mediate multiple aspects of EC function. An intensive crosstalk between cells via soluble factors, including cytokines, contributes to vessel structure, function, and maintenance, proliferation of ECs and vascular smooth muscle cells, EC-leukocyte interactions, platelet adhesion, coagulation, inflammation, and permeability [14].

ECs continuously communicate with other cells through a variety of mechanisms. A key mode of communication is the release of soluble cytokines and chemokines. These signals lead to the induction of biological processes, such as cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration that in turn influence the homeostasis of the tissues and organs by controlling the cell types and numbers that are produced [15]. The extracellular propagation of the signal is mediated by random molecular motion of the soluble cytokines- and chemokines. Although the cells cannot control diffusion, they can regulate their biological processes such as protein production and secretion rates.

3. Endothelial Cells and Extracellular Vesicles

3.1. Definition and Biogenesis of EVs

Intercellular connection by extracellular vesicles (EVs) is another way of cell to cell crosstalk that allows cells to deliver biological contents and messages to distant recipient cells. ECs constitutively secrete EVs into the blood in low concentrations under physiological conditions. It has been suggested that endothelial EVs account for approximately 5–15%, and constitute a large subclass of all circulating EVs in blood, albeit the majority of circulating plasma EVs are derived from platelets and erythrocytes [16]. However, the amount of EVs released by ECs remains difficult to estimate due in part to sampling artifacts and to a lack of standardization of the techniques for the isolation and characterization of EVs [17]. Plasma levels of endothelial EVs have been found to be elevated in various diseases involving EC injury or dysfunction [18].

MVs are large vesicles (100–1000 nm) that may display a diverse range of sizes and are released from the plasma membrane by budding. In contrast, exosomes are smaller vesicles (50–150 nm) that originate from the endosome [19].

All EVs bear surface molecules that allow them to be targeted to recipient cells. Once attached to a target cell, EVs can induce signaling via receptor–ligand interaction or can be internalized by endocytosis and/or phagocytosis or even fuse with the target cell’s membrane to deliver their content into its cytosol, thereby modifying the physiological state of the recipient cell [19][20]. An integrin-associated protein, CD47, which protects cells from phagocytosis, is often found on the surface of EVs and was shown to increase the time of EV circulation in the blood by preventing their phagocytosis by macrophages and monocytes [21].

3.2. Mechanims of EV Uptake and Cargo Delivery

In ECs, EV uptake has been shown to be mediated via the interaction of EV surface proteins such as tetraspanins with membrane receptors of the recipient cells [22]. Tumor-derived EVs bearing Tspan8-CD49d complexes have been shown to be internalized by vascular rat ECs, thereby enhancing EC migration, proliferation and sprouting [23]. EVs bearing Tspan8-α4 complexes were also found incorporated by rat ECs after binding to intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 [24]. EVs can also transmit information to recipient cells by EV/cell surface contact, without delivery of their content. As an example, during immune responses, EVs harboring major histocompatibility complex (MHC)–peptide complexes can activate cognate T cell receptors on T lymphocytes [25].

3.3. Endothelial Cell-Derived EVs

EC injury triggers the release of EC-derived EVs including both exosomes and MVs. Upon inflammation, the proinflammatory cytokine TNF leads to a dose-dependent increase in the release of endothelial EVs, which could be reversed by the use of blocking anti-TNF antibody [26]. Moreover, TNF promotes an induction of tissue factor (TF) on the surface of the endothelial EVs [26]. Stimulation of ECs with other inflammatory factors, including interleukin-1 (IL-1), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and bacterial lipopolysaccharide have also been shown to induce the release of endothelial EVs containing higher levels of specific miRNAs than endothelial EVs derived from unstimulated ECs [27]. In addition to proinflammatory cytokines, coagulation factors such as thrombin [28], C-reactive protein (CRP) [29], and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) [30] are also capable of inducing the release of EVs from ECs [18].

3.4. EVs Trigger Endothelial Protection and Vascular Repair

Several studies have shown that EVs of endothelial origin can act to promote EC and vascular integrity in vitro and in vivo. Abid Hussein et al. have demonstrated that endothelial MV release is cell protective by exporting caspase-3, one of the effector enzymes of apoptosis, into MVs and thereby diminishing intracellular levels of proapoptotic caspase-3 [31]. In a similar way, Jansen et al. have demonstrated that incorporation of annexin I/phosphatidylserine receptor-dependent endothelial MVs by ECs protects ECs against apoptosis by inhibiting MAPkinase p38 activity [32].

3.5. Transfert of miRNAs via EVs

EVs are fully active membrane vesicles that contain and transfer functional intracellular contents. EVs convey cellular messages through their distinct cargoes consisting of proteins, cytokines, mRNA, or noncoding RNA such as microRNA (miRNA) or long noncoding RNA (lnc RNA) to target cells and influence their function and their phenotype [33]. Among the biological contents transferred by EVs into target cells, miRNAs play a key role by controlling mRNA and protein expression in recipient cells [16]. MiRNAs regulate the expression of mRNAs at post transcriptional level either via translational repression or mRNA degradation [34].

Numerous in vitro studies have demonstrated that extracellular miRNAs enwrapped with exosomes can alter gene expression in the recipient cells such as ECs. For instance, exosomes derived from hypoxic leukemia cells contain a subset of upregulated miRNAs including miR-210 which may enhance tube formation in ECs [35]. Like exosomes, MVs can also carry miRNAs. The presence of miRNAs in MVs has been reported from different cells including ECs [36].

3.6. EVs and Immune Responses

Evidence is emerging that extracellular vesicles can act as triggers and regulators of immune responses in particular in cancer [37]. Indeed, besides molecules commonly found in most exosomes (adhesion molecules, heat shock proteins, molecules involved in membrane trafficking and ESCRT, etc.), molecules with specialized function in immune responses like MHC class I and II, costimulatory molecules and several immune receptors and ligands (such as FasL, TRAIL, PD-L1, NKG2D ligands) have been identified in the cargo of various exosomes. ECs express not only MHC class I and class II and most of costimulatory molecules displayed on antigen presenting cells such as dendritic cells [38], but also a set of non-classical and MHC class-I–like molecules including HLA-E, MICA and other NKG2D ligands that may potentially activate cognate receptors on natural killer (NK) and T cells [39][40].

4. Shedding of Endothelial Protein Ectodomains

In addition to the proteins that undergo protein secretion via secretory pathways, several membrane proteins are known to be released into the extracellular space via ectodomain shedding [41]. Previous studies on membrane proteins revealed that about 2–4% of cell surface molecules undergo the shedding process [42][43]. Several membrane-bound EC adhesion molecules, growth factors, cytokines, and cell receptors can be proteolytically cleaved by sheddases that results in the release of soluble forms of fragments. The process of ectodomain shedding has been shown to regulate vascular pathologies and diseases such as degeneration, inflammation, cancer and physiological processes such as proliferation, differentiation, and migration.

A recent database for the identification of shed membrane proteins revealed that a largest portion of the shed membrane proteins (34%) were found to be related to immune response, blood, homoeostasis and angiogenesis consistent with a major contribution of shedding in vascular biology [44]. Proteolytic removal of membrane protein ectodomains (ectodomain shedding) is a post-translational modification (PTM) that controls levels and function of numerous membrane proteins. The contributing proteases, referred to as sheddases, act as important molecular switches in processes ranging from signaling to cell adhesion. The shedding process consists on the proteolytic removal of membrane protein ectodomains (ectodomain shedding) by a protease (referred to as sheddase) which cleaves a membrane protein substrate close to or within its transmembrane (TM) domain. This results in release of the soluble ectodomain from the membrane and a fragment that remain bound to the membrane.

5. Endothelial Cells and Tunneling Nanotubes

6. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22157971

References

- Aird, W.C. Endothelium as an organ system. Crit. Care Med. 2004, 32, S271–S279.

- Pober, J.S.; Sessa, W.C. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2007, 7, 803–815.

- Pober, J.S.; Min, W.; Bradley, J.R. Mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction, injury, and death. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 2009, 4, 71–95.

- Bazzoni, G.; Dejana, E. Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: Molecular organization and role in vascular homeostasis. Physiol. Rev. 2004, 84, 869–901.

- Dejana, E.; Tournier-Lasserve, E.; Weinstein, B.M. The control of vascular integrity by endothelial cell junctions: Molecular basis and pathological implications. Dev. Cell 2009, 16, 209–221.

- Reininger, A.J. Function of von Willebrand factor in haemostasis and thrombosis. Haemophilia 2008, 14, 11–26.

- Springer, T.A. von Willebrand factor, Jedi knight of the bloodstream. Blood 2014, 124, 1412–1425.

- Giblin, J.P.; Hewlett, L.J.; Hannah, M.J. Basal secretion of von Willebrand factor from human endothelial cells. Blood 2008, 112, 957–964.

- Erent, M.; Meli, A.; Moisoi, N.; Babich, V.; Hannah, M.J.; Skehel, P.; Knipe, L.; Zupancic, G.; Ogden, D.; Carter, T. Rate, extent and concentration dependence of histamine-evoked Weibel-Palade body exocytosis determined from individual fusion events in human endothelial cells. J. Physiol. 2007, 583, 195–212.

- Van Agtmaal, E.L.; Bierings, R.; Dragt, B.S.; Leyen, T.A.; Fernandez-Borja, M.; Horrevoets, A.J.; Voorberg, J. The shear stress-induced transcription factor KLF2 affects dynamics and angiopoietin-2 content of Weibel-Palade bodies. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e38399.

- Schillemans, M.; Karampini, E.; Kat, M.; Bierings, R. Exocytosis of Weibel-Palade bodies: How to unpack a vascular emergency kit. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2019, 17, 6–18.

- Burgoyne, R.D.; Morgan, A. Secretory granule exocytosis. Physiol. Rev. 2003, 83, 581–632.

- Rothman, J.E. Intracellular membrane fusion. Adv. Second. Messenger Phosphoprot. Res. 1994, 29, 81–96.

- Banks, W.A.; Kovac, A.; Morofuji, Y. Neurovascular unit crosstalk: Pericytes and astrocytes modify cytokine secretion patterns of brain endothelial cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2018, 38, 1104–1118.

- Zlotnik, A.; Yoshie, O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity 2012, 36, 705–716.

- Diehl, P.; Fricke, A.; Sander, L.; Stamm, J.; Bassler, N.; Htun, N.; Ziemann, M.; Helbing, T.; El-Osta, A.; Jowett, J.B.; et al. Microparticles: Major transport vehicles for distinct microRNAs in circulation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2012, 93, 633–644.

- Gardiner, C.; Di Vizio, D.; Sahoo, S.; Thery, C.; Witwer, K.W.; Wauben, M.; Hill, A.F. Techniques used for the isolation and characterization of extracellular vesicles: Results of a worldwide survey. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2016, 5, 32945.

- Dignat-George, F.; Boulanger, C.M. The many faces of endothelial microparticles. Arter. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2011, 31, 27–33.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- Tkach, M.; Thery, C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell 2016, 164, 1226–1232.

- Kamerkar, S.; LeBleu, V.S.; Sugimoto, H.; Yang, S.; Ruivo, C.F.; Melo, S.A.; Lee, J.J.; Kalluri, R. Exosomes facilitate therapeutic targeting of oncogenic KRAS in pancreatic cancer. Nature 2017, 546, 498–503.

- Mulcahy, L.A.; Pink, R.C.; Carter, D.R. Routes and mechanisms of extracellular vesicle uptake. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2014, 3, 24641.

- Nazarenko, I.; Rana, S.; Baumann, A.; McAlear, J.; Hellwig, A.; Trendelenburg, M.; Lochnit, G.; Preissner, K.T.; Zoller, M. Cell surface tetraspanin Tspan8 contributes to molecular pathways of exosome-induced endothelial cell activation. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 1668–1678.

- Rana, S.; Yue, S.; Stadel, D.; Zoller, M. Toward tailored exosomes: The exosomal tetraspanin web contributes to target cell selection. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44, 1574–1584.

- Tkach, M.; Kowal, J.; Zucchetti, A.E.; Enserink, L.; Jouve, M.; Lankar, D.; Saitakis, M.; Martin-Jaular, L.; Thery, C. Qualitative differences in T-cell activation by dendritic cell-derived extracellular vesicle subtypes. EMBO J. 2017, 36, 3012–3028.

- Combes, V.; Simon, A.C.; Grau, G.E.; Arnoux, D.; Camoin, L.; Sabatier, F.; Mutin, M.; Sanmarco, M.; Sampol, J.; Dignat-George, F. In vitro generation of endothelial microparticles and possible prothrombotic activity in patients with lupus anticoagulant. J. Clin. Investig 1999, 104, 93–102.

- Yamamoto, S.; Niida, S.; Azuma, E.; Yanagibashi, T.; Muramatsu, M.; Huang, T.T.; Sagara, H.; Higaki, S.; Ikutani, M.; Nagai, Y.; et al. Inflammation-induced endothelial cell-derived extracellular vesicles modulate the cellular status of pericytes. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 8505.

- Sapet, C.; Simoncini, S.; Loriod, B.; Puthier, D.; Sampol, J.; Nguyen, C.; Dignat-George, F.; Anfosso, F. Thrombin-induced endothelial microparticle generation: Identification of a novel pathway involving ROCK-II activation by caspase-2. Blood 2006, 108, 1868–1876.

- Wang, J.M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, J.Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, L.C.; Tang, A.L.; Lou, Z.F.; Tao, J. C-Reactive protein-induced endothelial microparticle generation in HUVECs is related to BH4-dependent NO formation. J. Vasc. Res. 2007, 44, 241–248.

- Brodsky, S.V.; Malinowski, K.; Golightly, M.; Jesty, J.; Goligorsky, M.S. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes formation of endothelial microparticles with procoagulant potential. Circulation 2002, 106, 2372–2378.

- Abid Hussein, M.N.; Nieuwland, R.; Hau, C.M.; Evers, L.M.; Meesters, E.W.; Sturk, A. Cell-derived microparticles contain caspase 3 in vitro and in vivo. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2005, 3, 888–896.

- Jansen, F.; Yang, X.; Hoyer, F.F.; Paul, K.; Heiermann, N.; Becher, M.U.; Abu Hussein, N.; Kebschull, M.; Bedorf, J.; Franklin, B.S.; et al. Endothelial microparticle uptake in target cells is annexin I/phosphatidylserine receptor dependent and prevents apoptosis. Arter. Thromb Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 1925–1935.

- Jansen, F.; Li, Q.; Pfeifer, A.; Werner, N. Endothelial- and Immune Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in the Regulation of Cardiovascular Health and Disease. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 2017, 2, 790–807.

- Bartel, D.P. MicroRNAs: Genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–297.

- Tadokoro, H.; Umezu, T.; Ohyashiki, K.; Hirano, T.; Ohyashiki, J.H. Exosomes derived from hypoxic leukemia cells enhance tube formation in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34343–34351.

- Skog, J.; Wurdinger, T.; van Rijn, S.; Meijer, D.H.; Gainche, L.; Sena-Esteves, M.; Curry, W.T., Jr.; Carter, B.S.; Krichevsky, A.M.; Breakefield, X.O. Glioblastoma microvesicles transport RNA and proteins that promote tumour growth and provide diagnostic biomarkers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2008, 10, 1470–1476.

- Barros, F.M.; Carneiro, F.; Machado, J.C.; Melo, S.A. Exosomes and Immune Response in Cancer: Friends or Foes? Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 730.

- Choi, J.; Enis, D.R.; Koh, K.P.; Shiao, S.L.; Pober, J.S. T lymphocyte-endothelial cell interactions. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2004, 22, 683–709.

- Coupel, S.; Moreau, A.; Hamidou, M.; Horejsi, V.; Soulillou, J.P.; Charreau, B. Expression and release of soluble HLA-E is an immunoregulatory feature of endothelial cell activation. Blood 2007, 109, 2806–2814.

- Gavlovsky, P.J.; Tonnerre, P.; Guitton, C.; Charreau, B. Expression of MHC class I-related molecules MICA, HLA-E and EPCR shape endothelial cells with unique functions in innate and adaptive immunity. Hum. Immunol. 2016, 77, 1084–1091.

- Lichtenthaler, S.F.; Lemberg, M.K.; Fluhrer, R. Proteolytic ectodomain shedding of membrane proteins in mammals-hardware, concepts, and recent developments. EMBO J. 2018, 37, e99456.

- Arribas, J.; Massague, J. Transforming growth factor-alpha and beta-amyloid precursor protein share a secretory mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 1995, 128, 433–441.

- Hayashida, K.; Bartlett, A.H.; Chen, Y.; Park, P.W. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of ectodomain shedding. Anat. Rec.: Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2010, 293, 925–937.

- Tien, W.S.; Chen, J.H.; Wu, K.P. SheddomeDB: The ectodomain shedding database for membrane-bound shed markers. BMC Bioinform. 2017, 18, 42.

- Jansens, R.J.J.; Tishchenko, A.; Favoreel, H.W. Bridging the Gap: Virus Long-Distance Spread via Tunneling Nanotubes. J. Virol. 2020, 94.

- Rustom, A.; Saffrich, R.; Markovic, I.; Walther, P.; Gerdes, H.H. Nanotubular highways for intercellular organelle transport. Science 2004, 303, 1007–1010.

- Ramirez-Weber, F.A.; Kornberg, T.B. Cytonemes: Cellular processes that project to the principal signaling center in Drosophila imaginal discs. Cell 1999, 97, 599–607.

- Gerdes, H.H.; Carvalho, R.N. Intercellular transfer mediated by tunneling nanotubes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2008, 20, 470–475.

- Chinnery, H.R.; Pearlman, E.; McMenamin, P.G. Cutting edge: Membrane nanotubes in vivo: A feature of MHC class II+ cells in the mouse cornea. J. Immunol. 2008, 180, 5779–5783.

- Chauveau, A.; Aucher, A.; Eissmann, P.; Vivier, E.; Davis, D.M. Membrane nanotubes facilitate long-distance interactions between natural killer cells and target cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 5545–5550.

- Wang, X.; Gerdes, H.H. Long-distance electrical coupling via tunneling nanotubes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1818, 2082–2086.

- Watkins, S.C.; Salter, R.D. Functional connectivity between immune cells mediated by tunneling nanotubules. Immunity 2005, 23, 309–318.

- Osswald, M.; Jung, E.; Sahm, F.; Solecki, G.; Venkataramani, V.; Blaes, J.; Weil, S.; Horstmann, H.; Wiestler, B.; Syed, M.; et al. Brain tumour cells interconnect to a functional and resistant network. Nature 2015, 528, 93–98.

- Valadi, H.; Ekstrom, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjostrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lotvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Aird, W.C. Phenotypic heterogeneity of the endothelium: I. Structure, function, and mechanisms. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 158–173.

- Kalucka, J.; de Rooij, L.; Goveia, J.; Rohlenova, K.; Dumas, S.J.; Meta, E.; Conchinha, N.V.; Taverna, F.; Teuwen, L.A.; Veys, K.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of Murine Endothelial Cells. Cell 2020, 180, 764–779.e720.

- Ady, J.; Thayanithy, V.; Mojica, K.; Wong, P.; Carson, J.; Rao, P.; Fong, Y.; Lou, E. Tunneling nanotubes: An alternate route for propagation of the bystander effect following oncolytic viral infection. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 2016, 3, 16029.