Heart failure (HF) and cancer are the main public health issues in industrialized countries and are increasing in prevalence, especially, in the ageing population. These two diseases were thought to be independent; however, new research has revealed that cancer and HF frequently coexist in the same patient. Furthermore, as cancer-specific mortality decreases and the surviving population gets older, the overlap between cardiac disease and cancer patients is growing. As a result, the discipline of cardio-oncology has primarily focused on the adverse effects of anti-cancer therapy. HF is one of the most serious consequences of cardiotoxic cancer therapy.

- heart failure

- myocardial infarction

- cancer

- renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

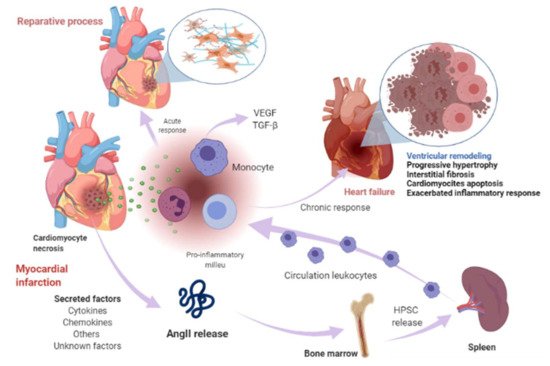

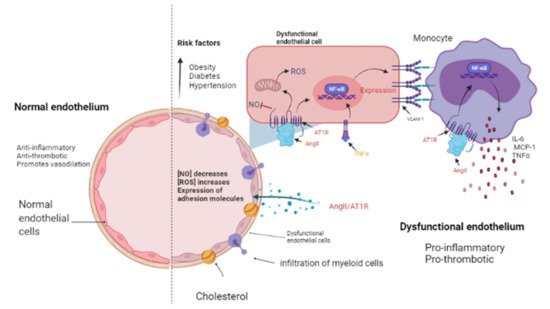

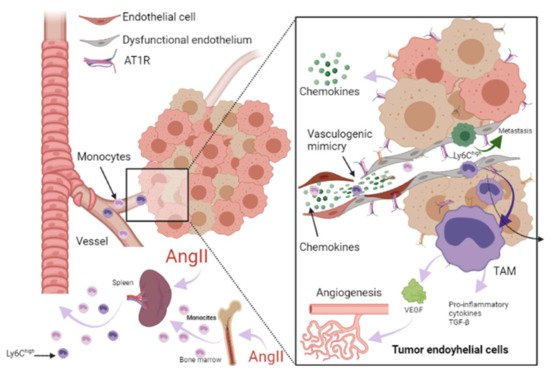

1. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Linking Ischemic Heart Failure and Cancer

2. Papel de la farmacoterapia con inhibidores del RAAS en la insuficiencia cardíaca y el cáncer

| RAAS Inhibitor | Observations |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) | |

| Captopril | Long-term administration was associated with an improvement in survival and reduced morbidity and mortality due to major cardiovascular events in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular (LV) dysfunction after myocardial infarction (MI) [55]. |

| Enalapril | Increased exercise time and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) [56]. |

| Perindopril | Increased 6 min walk distance but did not decrease mortality [57]. After 1-year treatment reduced progressive LV remodeling but it was not associated with better clinical outcomes [58]. |

| Ramipril | Administration to patients with clinical evidence of either transient or ongoing heart failure (HF) after MI resulted in a substantial reduction in premature death from all causes [59]. |

| Trandolapril | Long-term treatment in patients with reduced LV function soon after MI significantly reduced the risk of overall mortality, mortality from cardiovascular causes, sudden death, and the development of severe HF [60]. |

| Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs) | |

| Telmisartan | Telmisartan was well tolerated in patients unable to tolerate ACEI. Although the drug had no significant effect on hospitalizations for HF, it modestly reduced the risk of the composite outcome of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke [61]. |

| Candesartan | Slightly decreased hospitalizations but did not decrease mortality [62]. Reduced cardiovascular mortality and hospital admissions for worsening chronic HF. Patients with reduced ejection fraction were the most benefited [63]. |

| Losartan | Reduced the rate of death or admission for HF in patients with HF, reduced LVEF, and intolerance to ACEI [64]. |

| Valsartan | In patients with MI associated with HF and/or LV dysfunction, valsartan administration in the immediate post MI period demonstrated equal efficacy than captopril [65][66]. |

| Aldosterone antagonists | |

| Spironolactone | Prevented LV fibrosis and remodeling after MI [67] |

| RAAS Inhibitor | Findings |

|---|---|

| Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) | |

| Captopril | Inhibits tumor growth in a gastric cancer model and suppresses the angiogenesis of the tumor by decreasing the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-7 in a mouse model with human gastric cancer [68]. Attenuates cell migration in a breast cancer model [69]. Inhibits cell growth, decreases c-myc expression, and increases apoptosis on leukemic cell lines [70]. |

| Enalapril | Inhibits tumor progression and reduces number of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [23]. |

| Perindopril | Can inhibit the tumor growth in gastric cancer model and suppress the angiogenesis of the tumor by decreasing the expression of VEGF and MMP-7 in a mouse model with human gastric cancer [68]. |

| Ramipril | Decreases systemic inflammation [24]. |

| Trandolapril | Inhibits cell growth, decreases c-myc expression, and increases apoptosis in leukemic cell lines [70]. |

| Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers (ARBs) | |

| Telmisartan | Inhibits cell proliferation and tumor growth of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by inducing s-phase cell cycle arrest [71]. |

| Candesartan | Prevents bladder cancer growth in a mouse model by inhibiting angiogenesis, and combined treatment with candesartan and paclitaxel enhances paclitaxel-induced cytotoxicity [72]. Candesartan treatment significantly sensitizes human lung adenocarcinoma cells to tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-mediated apoptosis [73]. |

| Losartan | Can inhibit the tumor growth in gastric cancer model and suppress the angiogenesis of the tumor decreasing the expressions of VEGF [68]. Can exert anti-metastatic activity by inhibiting chemokine receptor type 2 (CCR2) signaling and suppressing monocyte recruitment in a mouse model with tumors and indirectly as anti-inflammatory effect and independently of AT1R [74]. Ameliorates angiogenesis, inflammation and the induction of oxidative stress via type-1 angiotensin-II receptor (AT1R) in a murine model of lung metastasis of colorectal cancer [75]. Inhibits cell growth, decreases c-myc expression and increases apoptosis in leukemic cell lines [70]. |

| Valsartan | Can inhibit the tumor growth in gastric cancer model and suppress the angiogenesis of the tumor, decreasing the expressions of VEGF [68]. |

| Aldosterone antagonists | |

| Spironolactone | Inhibits cancerous cell growth and is highly toxic for cancer stem cells; impairs DNA-double-strand breaks repair and induces apoptosis in cancer cells and cancer stem cells (CSCs) while sparing healthy cells. In vivo, this treatment reduces the size and CSC content of tumors [76]. |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22137106

References

- Paz Ocaranza, M.; Riquelme, J.A.; García, L.; Jalil, J.E.; Chiong, M.; Santos, R.A.S.; Lavandero, S. Counter-regulatory renin–angiotensin system in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2020, 17, 116–129.

- Pugliese, N.R.; Masi, S.; Taddei, S. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system: A crossroad from arterial hypertension to heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 31–42.

- Ziaja, M.; Urbanek, K.A.; Kowalska, K.; Piastowska-Ciesielska, A.W. Angiotensin II and Angiotensin Receptors 1 and 2—Multifunctional System in Cells Biology, What Do We Know? Cells 2021, 10, 381.

- Steckelings, U.M.; Paulis, L.; Namsolleck, P.; Unger, T. AT2 receptor agonists: Hypertension and beyond. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2012, 21, 142–146.

- Wang, Y.; Del Borgo, M.; Lee, H.W.; Baraldi, D.; Hirmiz, B.; Gaspari, T.A.; Denton, K.M.; Aguilar, M.I.; Samuel, C.S.; Widdop, R.E. Anti-fibrotic potential of AT2 receptor agonists. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 564.

- Rompe, F.; Artuc, M.; Hallberg, A.; Alterman, M.; Ströder, K.; Thöne-Reineke, C.; Reichenbach, A.; Schacherl, J.; Dahlöf, B.; Bader, M.; et al. Direct angiotensin II type 2 receptor stimulation acts anti-inflammatory through epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and inhibition of nuclear factor κb. Hypertension 2010, 55, 924–931.

- Pinter, M.; Jain, R.K. Targeting the renin-angiotensin system to improve cancer treatment: Implications for immunotherapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaan5616.

- Sheikh, S.P. Angiotensin Type 2 Receptor. In Encyclopedia of Signaling Molecules; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 320–327.

- Patel, V.B.; Zhong, J.C.; Grant, M.B.; Oudit, G.Y. Role of the ACE2/angiotensin 1-7 axis of the renin-angiotensin system in heart failure. Circ. Res. 2016, 118, 1313–1326.

- Wang, J.; He, W.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Han, S.; Shen, D. The ACE2-Ang (1-7)-Mas receptor axis attenuates cardiac remodeling and fibrosis in post-myocardial infarction. Mol. Med. Rep. 2017, 16, 1973–1981.

- da Silveira, K.D.; Coelho, F.M.; Vieira, A.T.; Sachs, D.; Barroso, L.C.; Costa, V.V.; Bretas, T.L.B.; Bader, M.; de Sousa, L.P.; da Silva, T.A.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of the Activation of the Angiotensin-(1–7) Receptor, Mas, in Experimental Models of Arthritis. J. Immunol. 2010, 185, 5569–5576.

- Chappell, M.C.; Al Zayadneh, E.M. Angiotensin-(1-7) and the Regulation of Anti-Fibrotic Signaling Pathways. J. Cell Signal. 2017, 2, 2.

- Park, B.M.; Cha, S.A.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, S.H. Angiotensin IV protects cardiac reperfusion injury by inhibiting apoptosis and inflammation via AT4R in rats. Peptides 2016, 79, 66–74.

- de Paula Gonzaga, A.L.A.C.; Palmeira, V.A.; Ribeiro, T.F.S.; Costa, L.B.; de Sá Rodrigues, K.E.; Simões-e-Silva, A.C. ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/Mas Receptor Axis in Human Cancer: Potential Role for Pediatric Tumors. Curr. Drug Targets 2020, 21, 892–901.

- Forrester, S.J.; Booz, G.W.; Sigmund, C.D.; Coffman, T.M.; Kawai, T.; Rizzo, V.; Scalia, R.; Eguchi, S. Angiotensin II signal transduction: An update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1627–1738.

- Bertero, E.; Ameri, P.; Maack, C. Bidirectional Relationship Between Cancer and Heart Failure: Old and New Issues in Cardio-oncology. Card. Fail. Rev. 2019, 5, 106–111.

- Emdin, M.; Fatini, C.; Mirizzi, G.; Poletti, R.; Borrelli, C.; Prontera, C.; Latini, R.; Passino, C.; Clerico, A.; Vergaro, G. Biomarkers of activation of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in heart failure: How useful, how feasible? Clin. Chim. Acta 2015, 443, 85–93.

- Dutta, P.; Courties, G.; Wei, Y.; Leuschner, F.; Gorbatov, R.; Robbins, C.S.; Iwamoto, Y.; Thompson, B.; Carlson, A.L.; Heidt, T.; et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates atherosclerosis. Nature 2012, 487, 325–329.

- Kyaw, T.; Loveland, P.; Kanellakis, P.; Cao, A.; Kallies, A.; Huang, A.L.; Peter, K.; Toh, B.-H.; Bobik, A. Alarmin-activated B cells accelerate murine atherosclerosis after myocardial infarction via plasma cell-immunoglobulin-dependent mechanisms. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 938–947.

- Orsborne, C.; Chaggar, P.S.; Shaw, S.M.; Williams, S.G. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in heart failure for the non-specialist: The past, the present and the future. Postgrad. Med. J. 2016, 93, 29–37.

- Rasini, E.; Cosentino, M.; Marino, F.; Legnaro, M.; Ferrari, M.; Guasti, L.; Venco, A.; Lecchini, S. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor expression on human leukocyte subsets: A flow cytometric and RT-PCR study. Regul. Pept. 2006, 134, 69–74.

- Kim, S.; Zingler, M.; Harrison, J.K.; Scott, E.W.; Cogle, C.R.; Luo, D.; Raizada, M.K. Angiotensin II Regulation of Proliferation, Differentiation, and Engraftment of Hematopoietic Stem Cells. Hypertension 2016, 67, 574–584.

- Cortez-Retamozo, V.; Etzrodt, M.; Newton, A.; Ryan, R.; Pucci, F.; Sio, S.W.; Kuswanto, W.; Rauch, P.J.; Chudnovskiy, A.; Iwamoto, Y.; et al. Angiotensin II Drives the Production of Tumor-Promoting Macrophages. Immunity 2013, 38, 296–308.

- Rudi, W.-S.; Molitor, M.; Garlapati, V.; Finger, S.; Wild, J.; Münzel, T.; Karbach, S.H.; Wenzel, P. ACE Inhibition Modulates Myeloid Hematopoiesis after Acute Myocardial Infarction and Reduces Cardiac and Vascular Inflammation in Ischemic Heart Failure. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 396.

- Frangogiannis, N.G. The immune system and the remodeling infarcted heart: Cell biological insights and therapeutic opportunities. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2014, 63, 185–195.

- Libby, P.; Nahrendorf, M.; Swirski, F.K. Leukocytes link local and systemic inflammation in ischemic cardiovascular disease an expanded cardiovascular continuum. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 67, 1091–1103.

- Katz, S.D. Mechanisms of Heart Failure BT—Management of Heart Failure: Volume 1: Medical; Baliga, R.R., Haas, G.J., Eds.; Springer: London, UK, 2015; pp. 13–30. ISBN 978-1-4471-6657-3.

- Meijers, W.C.; Maglione, M.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Oberhuber, R.; Kieneker, L.M.; De Jong, S.; Haubner, B.J.; Nagengast, W.B.; Lyon, A.R.; Van Der Vegt, B.; et al. Heart failure stimulates tumor growth by circulating factors. Circulation 2018, 138, 678–691.

- Dewey, C.M.; Spitler, K.M.; Ponce, J.M.; Hall, D.D.; Grueter, C.E. Cardiac-Secreted Factors as Peripheral Metabolic Regulators and Potential Disease Biomarkers. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e003101.

- George, A.J.; Thomas, W.G.; Hannan, R.D. The renin-angiotensin system and cancer: Old dog, new tricks. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 745–759.

- Clark, C.E.; Hingorani, S.R.; Mick, R.; Combs, C.; Tuveson, D.A.; Vonderheide, R.H. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 9518–9527.

- Kiss, M.; Caro, A.A.; Raes, G.; Laoui, D. Systemic Reprogramming of Monocytes in Cancer. Front. Oncol. 2020, 10, 1399.

- Singh, N.; Baby, D.; Rajguru, J.; Patil, P.; Thakkannavar, S.; Pujari, V. Inflammation and cancer. Ann. Afr. Med. 2019, 18, 121–126.

- Anderson, N.M.; Simon, M.C. The tumor microenvironment. Curr. Biol. 2020, 30, R921–R925.

- Koelwyn, G.J.; Newman, A.A.C.; Afonso, M.S.; van Solingen, C.; Corr, E.M.; Brown, E.J.; Albers, K.B.; Yamaguchi, N.; Narke, D.; Schlegel, M.; et al. Myocardial infarction accelerates breast cancer via innate immune reprogramming. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 1452–1458.

- Amin, M.N.; Siddiqui, S.A.; Ibrahim, M.; Hakim, M.L.; Ahammed, M.S.; Kabir, A.; Sultana, F. Inflammatory cytokines in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease and cancer. SAGE Open Med. 2020, 8, 2050312120965752.

- Becher, U.M.; Endtmann, C.; Tiyerili, V.; Nickenig, G.; Werner, N. Endothelial damage and regeneration: The role of the renin-angiotensin- aldosterone system. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2011, 13, 86–92.

- Silva, G.M.; França-Falcão, M.S.; Calzerra, N.T.M.; Luz, M.S.; Gadelha, D.D.A.; Balarini, C.M.; Queiroz, T.M. Role of Renin-Angiotensin System Components in Atherosclerosis: Focus on Ang-II, ACE2, and Ang-1–7. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 1067.

- Davel, A.P.; Anwar, I.J.; Jaffe, I.Z. The endothelial mineralocorticoid receptor: Mediator of the switch from vascular health to disease. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2017, 26, 97–104.

- Herrera-Zelada, N.; Zuñiga-Cuevas, U.; Ramirez-Reyes, A.; Lavandero, S.; Riquelme, J.A. Targeting the Endothelium to Achieve Cardioprotection. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 3.

- Toya, T.; Sara, J.D.; Corban, M.T.; Taher, R.; Godo, S.; Herrmann, J.; Lerman, L.O.; Lerman, A. Assessment of peripheral endothelial function predicts future risk of solid-tumor cancer. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020, 27, 608–618.

- Franses, J.W.; Drosu, N.C.; Gibson, W.J.; Chitalia, V.C.; Edelman, E.R. Dysfunctional endothelial cells directly stimulate cancer inflammation and metastasis. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 1334–1344.

- Molitor, M.; Rudi, W.S.; Garlapati, V.; Finger, S.; Schüler, R.; Kossmann, S.; Lagrange, J.; Nguyen, T.S.; Wild, J.; Knopp, T.; et al. Nox2+myeloid cells drive vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction in heart failure after myocardial infarction via angiotensin II receptor type 1. Cardiovasc. Res. 2021, 117, 162–177.

- Catarata, M.J.; Ribeiro, R.; Oliveira, M.J.; Cordeiro, C.R.; Medeiros, R. Renin-angiotensin system in lung tumor and microenvironment interactions. Cancers 2020, 12, 1457.

- Ishikane, S.; Takahashi-Yanaga, F. The role of angiotensin II in cancer metastasis: Potential of renin-angiotensin system blockade as a treatment for cancer metastasis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2018, 151, 96–103.

- Feng, L.-H.; Sun, H.-C.; Zhu, X.-D.; Zhang, S.-Z.; Li, X.-L.; Li, K.-S.; Liu, X.-F.; Lei, M.; Li, Y.; Tang, Z.-Y. Irbesartan inhibits metastasis by interrupting the adherence of tumor cell to endothelial cell induced by angiotensin II in hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2021, 9, 207.

- Patel, R.B.; Colangelo, L.A.; Bielinski, S.J.; Larson, N.B.; Ding, J.; Allen, N.B.; Michos, E.D.; Shah, S.J.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M. Circulating Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule-1 and Incident Heart Failure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA). J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020, 9, e019390.

- Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Soto-Reyes, E.; Vidal-Millán, S.; Sánchez-Corona, J. The renin-angiotensin system meets the hallmarks of cancer. JRAAS J. Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015, 16, 227–233.

- Carbajo-Lozoya, J.; Lutz, S.; Feng, Y.; Kroll, J.; Hammes, H.P.; Wieland, T. Angiotensin II modulates VEGF-driven angiogenesis by opposing effects of type 1 and type 2 receptor stimulation in the microvascular endothelium. Cell. Signal. 2012, 24, 1261–1269.

- Cespón-Fernández, M.; Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; Abu-Assi, E.; Manzano-Fernández, S.; Flores-Blanco, P.; Barreiro-Pardal, C.; Castiñeira-Busto, M.; Muñoz-Pousa, I.; López-Rodríguez, E.; Caneiro-Queija, B.; et al. Renin–Angiotensin System Blockade and Risk of Heart Failure After Myocardial Infarction Based on Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Am. J. Cardiovasc. Drugs 2019, 19, 487–495.

- Raposeiras-Roubín, S.; Abu-Assi, E.; Cespón-Fernández, M.; Ibáñez, B.; García-Ruiz, J.M.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Simao Henriques, J.P.; Saucedo, J.; Caneiro-Queija, B.; Cobas-Paz, R.; et al. Impact of renin-angiotensin system blockade on the prognosis of acute coronary syndrome based on left ventricular ejection fraction. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2020, 73, 114–122.

- Sim, H.W.; Zheng, H.; Richards, A.M.; Chen, R.W.; Sahlen, A.; Yeo, K.K.; Tan, J.W.; Chua, T.; Tan, H.C.; Yeo, T.C.; et al. Beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors in acute myocardial infarction managed with inhospital coronary revascularization. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15184.

- Ranjbar, R.; Shafiee, M.; Hesari, A.R.; Ferns, G.A.; Ghasemi, F.; Avan, A. The potential therapeutic use of renin–angiotensin system inhibitors in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. J. Cell. Physiol. 2019, 234, 2277–2295.

- Yang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, X.; Yao, Y.; Huang, C.; Liu, L. The Relationship Between Anti-Hypertensive Drugs and Cancer: Anxiety to be Resolved in Urgent. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 2122.

- Pfeffer, M.A.; Braunwald, E.; Moyé, L.A.; Basta, L.; Brown, E.J.; Cuddy, T.E.; Davis, B.R.; Geltman, E.M.; Goldman, S.; Flaker, G.C.; et al. Effect of Captopril on Mortality and Morbidity in Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction after Myocardial Infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 1992, 327, 669–677.

- Aronow, W.S.; Kronzon, I. Effect of enalapril on congestive heart failure treated with diuretics in elderly patients with prior myocardial infarction and normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Am. J. Cardiol. 1993, 71, 602–604.

- Cleland, J.G.F.; Tendera, M.; Adamus, J.; Freemantle, N.; Gray, C.S.; Lye, M.; O’Mahony, D.; Polonski, L.; Taylor, J. Perindopril for elderly people with chronic heart failure: The PEP-CHF study. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 1999, 1, 211–217.

- Ferrari, R. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition with perindopril on left ventricular remodeling and clinical outcome: Results of the randomized Perindopril and Remodeling in Elderly with Acute Myocardial Infarction (PREAMI) study. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006, 166, 659–666.

- The Acute Infarction Ramipril Efficacy (AIRE) Study Investigators Effect of ramipril on mortality and morbidity of survivors of acute myocardial infarction with clinical evidence of heart failure. Lancet 1993, 342, 821–828.

- Tepper, D.; Greenberg, S. A clinical trial of the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor trandolapril in patients with left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc. Rev. Rep. 1996, 17, 49.

- The Telmisartan Randomised AssessmeNt Study in ACE iNtolerant Subjects with Cardiovascular Disease (TRANSCEND) Investigators; Yusuf, S.; Teo, K.; Anderson, C.; Pogue, J.; Dyal, L.; Copland, I.; Schumacher, H.; Dagenais, G.; Sleight, P. Effects of the angiotensin-receptor blocker telmisartan on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients intolerant to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 372, 1174–1183.

- Yusuf, S.; Pfeffer, M.A.; Swedberg, K.; Granger, C.B.; Held, P.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Michelson, E.L.; Olofsson, B.; Östergren, J. Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and preserved left-ventricular ejection fraction: The CHARM-preserved trial. Lancet 2003, 362, 777–781.

- Pfeffer, M.A.; McMurray, J.J.; Östergren, J.; Granger, C.B.; Yusuf, S.; Pitt, B. Candesartan reduced mortality and hospital admissions in chronic heart failure. Evid. Based. Med. 2004, 9, 44–45.

- Konstam, M.A.; Neaton, J.D.; Dickstein, K.; Drexler, H.; Komajda, M.; Martinez, F.A.; Riegger, G.A.; Malbecq, W.; Smith, R.D.; Guptha, S.; et al. Effects of high-dose versus low-dose losartan on clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure (HEAAL study): A randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 2009, 374, 1840–1848.

- Pfeffer, M.A.; McMurray, J.; Leizorovicz, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Rouleau, J.L.; Van De Werf, F.; Henis, M.; Neuhart, E.; Gallo, P.; Edwards, S.; et al. Valsartan in acute myocardial infarction trial (VALIANT): Rationale and design. Am. Heart J. 2000, 140, 727–750.

- Bissessor, N.; White, H. Valsartan in the treatment of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction after myocardial infarction. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2007, 3, 425–430.

- Hayashi, M.; Tsutamoto, T.; Wada, A.; Tsutsui, T.; Ishii, C.; Ohno, K.; Fujii, M.; Taniguchi, A.; Hamatani, T.; Nozato, Y.; et al. Immediate administration of mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist spironolactone prevents post-infarct left ventricular remodeling associated with suppression of a marker of myocardial collagen synthesis in patients with first anterior acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 2003, 107, 2559–2565.

- Wang, L.; Cai, S.R.; Zhang, C.H.; He, Y.L.; Zhan, W.H.; Wu, H.; Peng, J.J. Effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers on lymphangiogenesis of gastric cancer in a nude mouse model. Chin. Med. J. 2008, 121, 2167–2171.

- Rasha, F.; Kahathuduwa, C.; Ramalingam, L.; Hernandez, A.; Moussa, H.; Moustaid-Moussa, N. Combined Effects of Eicosapentaenoic Acid and Adipocyte Renin–Angiotensin System Inhibition on Breast Cancer Cell Inflammation and Migration. Cancers 2020, 12, 220.

- De la Iglesia Iñigo, S.; López-Jorge, C.E.; Gómez-Casares, M.T.; Lemes Castellano, A.; Martín Cabrera, P.; López Brito, J.; Suárez Cabrera, A.; Molero Labarta, T. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cell lines treated with captopril, trandolapril and losartan: A new role in the treatment of leukaemia for these agents. Leuk. Res. 2009, 33, 810–816.

- Matsui, T.; Chiyo, T.; Kobara, H.; Fujihara, S.; Fujita, K.; Namima, D.; Nakahara, M.; Kobayashi, N.; Nishiyama, N.; Yachida, T.; et al. Telmisartan Inhibits Cell Proliferation and Tumor Growth of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma by Inducing S-Phase Arrest In Vitro and In Vivo. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3197.

- Kosugi, M.; Miyajima, A.; Kikuchi, E.; Kosaka, T.; Horiguchi, Y.; Murai, M. Effect of angiotensin II type 1 receptor antagonist on tumor growth and angiogenesis in a xenograft model of human bladder cancer. Hum. Cell 2007, 20, 1–9.

- Rasheduzzaman, M.; Park, S.Y. Antihypertensive drug-candesartan attenuates TRAIL resistance in human lung cancer via AMPK-mediated inhibition of autophagy flux. Exp. Cell Res. 2018, 368, 126–135.

- Regan, D.P.; Coy, J.W.; Chahal, K.K.; Chow, L.; Kurihara, J.N.; Guth, A.M.; Kufareva, I.; Dow, S.W. The Angiotensin Receptor Blocker Losartan Suppresses Growth of Pulmonary Metastases via AT1R-Independent Inhibition of CCR2 Signaling and Monocyte Recruitment. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 3087–3102.

- Hashemzehi, M.; Naghibzadeh, N.; Asgharzadeh, F.; Mostafapour, A.; Hassanian, S.M.; Ferns, G.A.; Cho, W.C.; Avan, A.; Khazaei, M. The therapeutic potential of losartan in lung metastasis of colorectal cancer. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 927–935.

- Gold, A.; Eini, L.; Nissim-Rafinia, M.; Viner, R.; Ezer, S.; Erez, K.; Aqaqe, N.; Hanania, R.; Milyavsky, M.; Meshorer, E.; et al. Spironolactone inhibits the growth of cancer stem cells by impairing DNA damage response. Oncogene 2019, 38, 3103–3118.