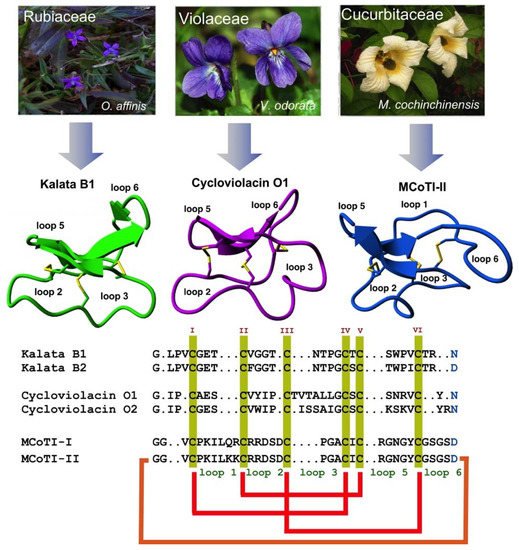

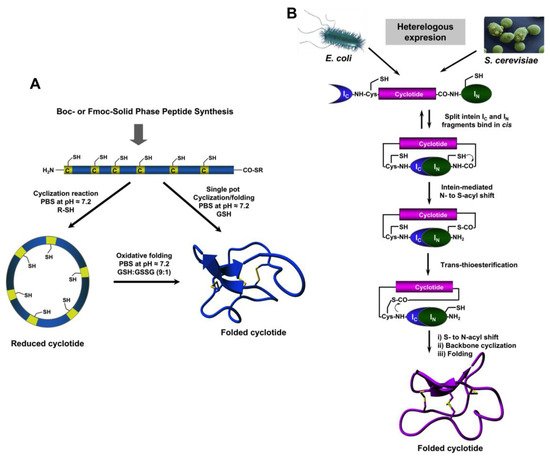

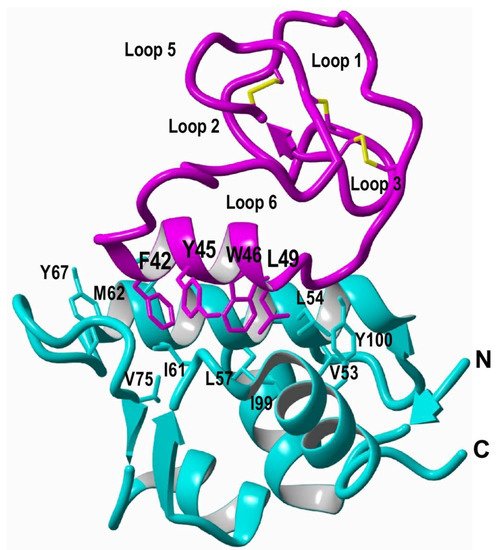

Cyclotides are a novel class of micro-proteins (≈30–40 residues long) with a unique topology containing a head-to-tail cyclized backbone structure further stabilized by three disulfide bonds that form a cystine knot. This unique molecular framework makes them exceptionally stable to physical, chemical, and biological degradation compared to linear peptides of similar size. The cyclotides are also highly tolerant to sequence variability, aside from the conserved residues forming the cystine knot, and are orally bioavailable and able to cross cellular membranes to modulate intracellular protein–protein interactions (PPIs), both in vitro and in vivo. These unique properties make them ideal scaffolds for many biotechnological applications, including drug discovery.

- cyclotides

- CCK

- cystine-knot

- drug design

- backbone cyclized polypeptides

- protein-protein interactions

- cyclic peptides

1. Introduction

2. Structure

3. Biosynthesis

4. Chemical Synthesis

5. Recombinant Expression

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines7020031

References

- Jubb, H.; Higueruelo, A.P.; Winter, A.; Blundell, T.L. Structural biology and drug discovery for protein-protein interactions. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012, 33, 241–248.

- Zinzalla, G.; Thurston, D.E. Targeting protein-protein interactions for therapeutic intervention: A challenge for the future. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 65–93.

- Fry, D.C.; Vassilev, L.T. Targeting protein-protein interactions for cancer therapy. J. Mol. Med. 2005, 83, 955–963.

- Qian, Z.; Dougherty, P.G.; Pei, D. Targeting intracellular protein-protein interactions with cell-permeable cyclic peptides. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 80–86.

- Ji, Y.; Majumder, S.; Millard, M.; Borra, R.; Bi, T.; Elnagar, A.Y.; Neamati, N.; Shekhtman, A.; Camarero, J.A. In vivo activation of the p53 tumor suppressor pathway by an engineered cyclotide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 11623–11633.

- Sheng, C.; Dong, G.; Miao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Wang, W. State-of-the-art strategies for targeting protein–protein interactions by small-molecule inhibitors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 8238–8259.

- Laraia, L.; McKenzie, G.; Spring, D.R.; Venkitaraman, A.R.; Huggins, D.J. Overcoming chemical, biological, and computational challenges in the development of inhibitors targeting protein-protein interactions. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 689–703.

- Stumpp, M.T.; Binz, H.K.; Amstutz, P. Darpins: A new generation of protein therapeutics. Drug Discov. Today 2008, 13, 695–701.

- Ferrara, N.; Hillan, K.J.; Gerber, H.P.; Novotny, W. Discovery and development of bevacizumab, an anti-vegf antibody for treating cancer. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2004, 3, 391–400.

- Holliger, P.; Hudson, P.J. Engineered antibody fragments and the rise of single domains. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 1126–1136.

- Klint, J.K.; Senff, S.; Rupasinghe, D.B.; Er, S.Y.; Herzig, V.; Nicholson, G.M.; King, G.F. Spider-venom peptides that target voltage-gated sodium channels: Pharmacological tools and potential therapeutic leads. Toxicon 2012, 60, 478–491.

- Wurch, T.; Pierre, A.; Depil, S. Novel protein scaffolds as emerging therapeutic proteins: From discovery to clinical proof-of-concept. Trends Biotechnol. 2012, 30, 575–582.

- Lewis, R.J. Discovery and development of the chi-conopeptide class of analgesic peptides. Toxicon 2012, 59, 524–528.

- Sancheti, H.; Camarero, J.A. “Splicing up” drug discovery. Cell-based expression and screening of genetically-encoded libraries of backbone-cyclized polypeptides. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 908–917.

- Bloom, L.; Calabro, V. Fn3: A new protein scaffold reaches the clinic. Drug Discov. Today 2009, 14, 949–955.

- Lewis, R.J. Conotoxin venom peptide therapeutics. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2009, 655, 44–48.

- Chaudhuri, D.; Aboye, T.; Camarero, J.A. Using backbone-cyclized cys-rich polypeptides as molecular scaffolds to target protein-protein interactions. Biochem. J 2019, 476, 67–83.

- Wang, C.K.; Craik, D.J. Designing macrocyclic disulfide-rich peptides for biotechnological applications. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 417–427.

- Craik, D.J.; Lee, M.H.; Rehm, F.B.H.; Tombling, B.; Doffek, B.; Peacock, H. Ribosomally-synthesised cyclic peptides from plants as drug leads and pharmaceutical scaffolds. Biorg. Med. Chem. 2018, 26, 2727–2737.

- Poth, A.G.; Colgrave, M.L.; Lyons, R.E.; Daly, N.L.; Craik, D.J. Discovery of an unusual biosynthetic origin for circular proteins in legumes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10127–10132.

- Gould, A.; Camarero, J.A. Cyclotides: Overview and biotechnological applications. ChemBioChem 2017, 18, 1350–1363.

- Craik, D.J.; Du, J. Cyclotides as drug design scaffolds. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2017, 38, 8–16.

- Camarero, J.A. Cyclotides, a versatile ultrastable micro-protein scaffold for biotechnological applications. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 5089–5099.

- Rosengren, K.J.; Daly, N.L.; Plan, M.R.; Waine, C.; Craik, D.J. Twists, knots, and rings in proteins. Structural definition of the cyclotide framework. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 8606–8616.

- Felizmenio-Quimio, M.E.; Daly, N.L.; Craik, D.J. Circular proteins in plants: Solution structure of a novel macrocyclic trypsin inhibitor from momordica cochinchinensis. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 22875–22882.

- Saether, O.; Craik, D.J.; Campbell, I.D.; Sletten, K.; Juul, J.; Norman, D.G. Elucidation of the primary and three-dimensional structure of the uterotonic polypeptide kalata b1. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 4147–4158.

- Li, Y.; Bi, T.; Camarero, J.A. Chemical and biological production of cyclotides. Adv. Bot. Res. 2015, 76, 271–303.

- Contreras, J.; Elnagar, A.Y.; Hamm-Alvarez, S.F.; Camarero, J.A. Cellular uptake of cyclotide mcoti-i follows multiple endocytic pathways. J. Control. Release 2011, 155, 134–143.

- Cascales, L.; Henriques, S.T.; Kerr, M.C.; Huang, Y.H.; Sweet, M.J.; Daly, N.L.; Craik, D.J. Identification and characterization of a new family of cell-penetrating peptides: Cyclic cell-penetrating peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36932–36943.

- Wong, C.T.; Rowlands, D.K.; Wong, C.H.; Lo, T.W.; Nguyen, G.K.; Li, H.Y.; Tam, J.P. Orally active peptidic bradykinin b1 receptor antagonists engineered from a cyclotide scaffold for inflammatory pain treatment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51, 5620–5624.

- Thell, K.; Hellinger, R.; Sahin, E.; Michenthaler, P.; Gold-Binder, M.; Haider, T.; Kuttke, M.; Liutkeviciute, Z.; Goransson, U.; Grundemann, C.; et al. Oral activity of a nature-derived cyclic peptide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 3960–3965.

- Puttamadappa, S.S.; Jagadish, K.; Shekhtman, A.; Camarero, J.A. Backbone dynamics of cyclotide mcoti-i free and complexed with trypsin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2010, 49, 7030–7034.

- Colgrave, M.L.; Craik, D.J. Thermal, chemical, and enzymatic stability of the cyclotide kalata b1: The importance of the cyclic cystine knot. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 5965–5975.

- Garcia, A.E.; Camarero, J.A. Biological activities of natural and engineered cyclotides, a novel molecular scaffold for peptide-based therapeutics. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2010, 3, 153–163.

- Gran, L. Oxytocic principles of oldenlandia affinis. Lloydia 1973, 36, 174–178.

- Gran, L. On the effect of a polypeptide isolated from “kalata-kalata” (oldenlandia affinis dc) on the oestrogen dominated uterus. Acta Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1973, 33, 400–408.

- Weidmann, J.; Craik, D.J. Discovery, structure, function, and applications of cyclotides: Circular proteins from plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 4801–4812.

- Wang, C.K.; Kaas, Q.; Chiche, L.; Craik, D.J. Cybase: A database of cyclic protein sequences and structures, with applications in protein discovery and engineering. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, D206–D210.

- Aboye, T.L.; Clark, R.J.; Burman, R.; Roig, M.B.; Craik, D.J.; Goransson, U. Interlocking disulfides in circular proteins: Toward efficient oxidative folding of cyclotides. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 77–86.

- Heitz, A.; Hernandez, J.F.; Gagnon, J.; Hong, T.T.; Pham, T.T.; Nguyen, T.M.; Le-Nguyen, D.; Chiche, L. Solution structure of the squash trypsin inhibitor mcoti-ii. A new family for cyclic knottins. Biochemistry 2001, 40, 7973–7983.

- Mylne, J.S.; Chan, L.Y.; Chanson, A.H.; Daly, N.L.; Schaefer, H.; Bailey, T.L.; Nguyencong, P.; Cascales, L.; Craik, D.J. Cyclic peptides arising by evolutionary parallelism via asparaginyl-endopeptidase-mediated biosynthesis. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2765–2778.

- Du, J.; Chan, L.Y.; Poth, A.G.; Craik, D.J. Discovery and characterization of cyclic and acyclic trypsin inhibitors from momordica dioica. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 293–300.

- Quimbar, P.; Malik, U.; Sommerhoff, C.P.; Kaas, Q.; Chan, L.Y.; Huang, Y.H.; Grundhuber, M.; Dunse, K.; Craik, D.J.; Anderson, M.A.; et al. High-affinity cyclic peptide matriptase inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 13885–13896.

- Chiche, L.; Heitz, A.; Gelly, J.C.; Gracy, J.; Chau, P.T.; Ha, P.T.; Hernandez, J.F.; Le-Nguyen, D. Squash inhibitors: From structural motifs to macrocyclic knottins. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2004, 5, 341–349.

- Ravipati, A.S.; Henriques, S.T.; Poth, A.G.; Kaas, Q.; Wang, C.K.; Colgrave, M.L.; Craik, D.J. Lysine-rich cyclotides: A new subclass of circular knotted proteins from violaceae. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 2491–2500.

- Craik, D.J.; Malik, U. Cyclotide biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2013, 17, 546–554.

- Jennings, C.; West, J.; Waine, C.; Craik, D.; Anderson, M. Biosynthesis and insecticidal properties of plant cyclotides: The cyclic knotted proteins from oldenlandia affinis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 10614–10619.

- Arnison, P.G.; Bibb, M.J.; Bierbaum, G.; Bowers, A.A.; Bugni, T.S.; Bulaj, G.; Camarero, J.A.; Campopiano, D.J.; Challis, G.L.; Clardy, J.; et al. Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: Overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2013, 30, 108–160.

- Saska, I.; Gillon, A.D.; Hatsugai, N.; Dietzgen, R.G.; Hara-Nishimura, I.; Anderson, M.A.; Craik, D.J. An asparaginyl endopeptidase mediates in vivo protein backbone cyclization. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 29721–29728.

- Poth, A.G.; Mylne, J.S.; Grassl, J.; Lyons, R.E.; Millar, A.H.; Colgrave, M.L.; Craik, D.J. Cyclotides associate with leaf vasculature and are the products of a novel precursor in petunia (solanaceae). J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 27033–27046.

- Nguyen, G.K.; Zhang, S.; Nguyen, N.T.; Nguyen, P.Q.; Chiu, M.S.; Hardjojo, A.; Tam, J.P. Discovery and characterization of novel cyclotides originated from chimeric precursors consisting of albumin-1 chain a and cyclotide domains in the fabaceae family. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 24275–24287.

- Gillon, A.D.; Saska, I.; Jennings, C.V.; Guarino, R.F.; Craik, D.J.; Anderson, M.A. Biosynthesis of circular proteins in plants. Plant J. 2008, 53, 505–515.

- Nguyen, G.K.; Wang, S.; Qiu, Y.; Hemu, X.; Lian, Y.; Tam, J.P. Butelase 1 is an asx-specific ligase enabling peptide macrocyclization and synthesis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 732–738.

- Harris, K.S.; Durek, T.; Kaas, Q.; Poth, A.G.; Gilding, E.K.; Conlan, B.F.; Saska, I.; Daly, N.L.; van der Weerden, N.L.; Craik, D.J.; et al. Efficient backbone cyclization of linear peptides by a recombinant asparaginyl endopeptidase. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 10199.

- Poon, S.; Harris, K.S.; Jackson, M.A.; McCorkelle, O.C.; Gilding, E.K.; Durek, T.; van der Weerden, N.L.; Craik, D.J.; Anderson, M.A. Co-expression of a cyclizing asparaginyl endopeptidase enables efficient production of cyclic peptides in planta. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 633–641.

- Bernath-Levin, K.; Nelson, C.; Elliott, A.G.; Jayasena, A.S.; Millar, A.H.; Craik, D.J.; Mylne, J.S. Peptide macrocyclization by a bifunctional endoprotease. Chem. Biol. 2015, 22, 571–582.

- Hemu, X.; Qiu, Y.; Nguyen, G.K.; Tam, J.P. Total synthesis of circular bacteriocins by butelase 1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 6968–6971.

- Nguyen, G.K.; Hemu, X.; Quek, J.P.; Tam, J.P. Butelase-mediated macrocyclization of d-amino-acid-containing peptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55, 12802–12806.

- Nguyen, G.K.; Qiu, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hemu, X.; Liu, C.F.; Tam, J.P. Butelase-mediated cyclization and ligation of peptides and proteins. Nat. Protoc. 2016, 11, 1977–1988.

- Jackson, M.A.; Gilding, E.K.; Shafee, T.; Harris, K.S.; Kaas, Q.; Poon, S.; Yap, K.; Jia, H.; Guarino, R.; Chan, L.Y.; et al. Molecular basis for the production of cyclic peptides by plant asparaginyl endopeptidases. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2411.

- Zauner, F.B.; Elsasser, B.; Dall, E.; Cabrele, C.; Brandstetter, H. Structural analyses of arabidopsis thaliana legumain gamma reveal differential recognition and processing of proteolysis and ligation substrates. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 8934–8946.

- Aboye, T.; Kuang, Y.; Neamati, N.; Camarero, J.A. Rapid parallel synthesis of bioactive folded cyclotides by using a tea-bag approach. ChemBioChem 2015, 16, 827–833.

- Lesniak, W.G.; Aboye, T.; Chatterjee, S.; Camarero, J.A.; Nimmagadda, S. In vivo evaluation of an engineered cyclotide as specific cxcr4 imaging reagent. Chemistry 2017, 23, 14469–14475.

- Aboye, T.; Meeks, C.J.; Majumder, S.; Shekhtman, A.; Rodgers, K.; Camarero, J.A. Design of a mcoti-based cyclotide with angiotensin (1-7)-like activity. Molecules 2016, 21, 152.

- Aboye, T.L.; Li, Y.; Majumder, S.; Hao, J.; Shekhtman, A.; Camarero, J.A. Efficient one-pot cyclization/folding of rhesus theta-defensin-1 (rtd-1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012, 22, 2823–2826.

- Li, Y.; Gould, A.; Aboye, T.; Bi, T.; Breindel, L.; Shekhtman, A.; Camarero, J.A. Full sequence amino acid scanning of theta-defensin rtd-1 yields a potent anthrax lethal factor protease inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1916–1927.

- Jagadish, K.; Borra, R.; Lacey, V.; Majumder, S.; Shekhtman, A.; Wang, L.; Camarero, J.A. Expression of fluorescent cyclotides using protein trans-splicing for easy monitoring of cyclotide-protein interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2013, 52, 3126–3131.

- Jagadish, K.; Gould, A.; Borra, R.; Majumder, S.; Mushtaq, Z.; Shekhtman, A.; Camarero, J.A. Recombinant expression and phenotypic screening of a bioactive cyclotide against alpha-synuclein-induced cytotoxicity in baker’s yeast. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2015, 54, 8390–8394.

- Jagadish, K.; Camarero, J.A. Recombinant expression of cyclotides using split inteins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1495, 41–55.

- Yang, R.; Wong, Y.H.; Nguyen, G.K.T.; Tam, J.P.; Lescar, J.; Wu, B. Engineering a catalytically efficient recombinant protein ligase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5351–5358.

- Thongyoo, P.; Roque-Rosell, N.; Leatherbarrow, R.J.; Tate, E.W. Chemical and biomimetic total syntheses of natural and engineered mcoti cyclotides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 1462–1470.

- Jia, X.; Kwon, S.; Wang, C.I.; Huang, Y.H.; Chan, L.Y.; Tan, C.C.; Rosengren, K.J.; Mulvenna, J.P.; Schroeder, C.I.; Craik, D.J. Semienzymatic cyclization of disulfide-rich peptides using sortase a. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 6627–6638.

- Aboye, T.L.; Camarero, J.A. Biological synthesis of circular polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 27026–27032.

- Kimura, R.H.; Tran, A.T.; Camarero, J.A. Biosynthesis of the cyclotide kalata b1 by using protein splicing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2006, 45, 973–976.

- Austin, J.; Kimura, R.H.; Woo, Y.H.; Camarero, J.A. In vivo biosynthesis of an ala-scan library based on the cyclic peptide sfti-1. Amino Acids 2010, 38, 1313–1322.

- Seydel, P.; Dornenburg, H. Establishment of in vitro plants, cell and tissue cultures from oldenlandia affinis for the production of cyclic peptides. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2006, 85, 247–255.