The expanding clinical application of CDK4- and CDK6-inhibiting drugs in the managements of breast cancer has raised a great interest in testing these drugs in other neoplasms. The potential of combining these drugs with other therapeutic approaches seems to be an interesting work-ground to explore. Even though a potential integration of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors with radiotherapy (RT) has been hypothesized, this kind of approach has not been sufficiently pursued, neither in preclinical nor in clinical studies. Similarly, the most recent discoveries focusing on autophagy, as a possible target pathway able to enhance the antitumor efficacy of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors is promising but needs more investigations.

1. Introduction

The expanding clinical application of CDK4- and CDK6-inhibiting drugs in the management of hormone-sensitive breast cancer [

1,

2,

3,

4] has raised a great interest in also testing these G1/S cell-cycle blocking agents in other neoplasms [

5,

6,

7], for which the potential clinical benefit is still largely unknown.

The innovative use of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors in combination with hormone therapy (HT) as a treatment for estrogen receptor positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 negative (ESR+/HER2−) metastatic breast cancer (BC) patientsis safe and successful in term of response rate (RR), progression-free survival (PFS), and overall survival (OS). Nevertheless, 10% of patients are refractory to this treatment whereas half of the patients show progression within 24 months of therapy [

8]. Therefore, to fully unleash their impact, combining these drugs with other therapeutic approaches seems a rational work-ground to explore.

Even though a potential integration of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors with radiotherapy (RT) has been hypothesized, this kind of approach has not been sufficiently pursued, neither in preclinical nor in clinical studies. Similarly, the most recent discoveries focusing on autophagy as a possible target pathway able to enhance the antitumor efficacy of CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors are promising but need more investigation.

3. The State of the Art in the Clinical Domain

3.1. Clinical Trials of Cyclin-D1/CDK4 and CDK6 Inhibition in Breast Cancer

In a phase II clinical trial (PALOMA-1), the addition of palbociclib to letrozole significantly increased the median progression-free survival (PFS) from 10.2 months to 20.2 months [

15] vs. letrozole alone for post-menopausal women with previously untreated ESR1+/HER2− advanced breast cancer. Palbociclib received accelerated approval by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in February 2015 [

65]. The placebo-randomized, double-blind, controlled phase III trial (PALOMA-3) compared treatment with palbociclib and fulvestrant to fulvestrant plus placebo in women with ESR1+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer that had relapsed or progressed on prior hormone therapy, including a substantial portion of patients (33%) with prior chemotherapy for metastatic disease. The interim analysis of this study demonstrated a significantly improved median PFS (9.5 months versus 4.6 months, respectively) [

12,

66]. Palbociclib is presently under further investigation in over 50 trials in related clinical settings.

Ribociclib is a selective strong inhibitor of CDK4 and CDK6 [

13], blocks Rb phosphorylation, and causes cell cycle arrest of Rb-positive tumor cells, similarly to palbociclib [

14]. The MONALEESA-2 trial demonstrated that ribociclib plus letrozole significantly improved progression-free survival, compared with placebo plus letrozole as a first-line therapy in postmenopausal patients with HR-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer [

15].

Ongoing trials are demonstrating significant progression-free survival improvements with ribociclib in different settings [

67,

68]. However, both palpociclib and ribociclib were characterized by a not-negligible systemic toxicity [

31].

Abemaciclib was tested in a phase I trial, showing efficacy against non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma, and mantle cell lymphoma, in addition to breast cancer [

69]. In fact, other than its high affinity for CCND1/CDK4, it also inhibits cyclin-B/CDK1 (related to G2 arrest) and cyclin E-A/CDK2 (related to palpociclib resistance). Differently from the cytostatic effect alpociclib and ribociclib, abemaciclib achieved a durable cytotoxic effect in Rb-negative cells [

70]. Moreover, in a first line randomized phase III double-blind study (MONARCH 3) for ESR1+/HER2− advanced breast cancer, abemaciclib presented a better hematological tolerability compared to palpociclib and ribociclib, and achieved impressive results in terms of PFS and objective response rate (ORR) [

71].

A synthesis of these clinical trials is reported in Table 1.

Table 1. Synthesis of the registrative clinical trials of cyclin inhibitors in metastatic breast cancer.

| Scheme. |

INTERVENTION |

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS |

MEDIAN PFS(Months) |

Clinical Gain/Approval |

| PALOMA-1 |

Palbociclib + letrozole

vs.

letrozole alone |

Post-menopausal women with untreated ER+/HER2−advanced breast cancer |

20.2

vs.

10.2 |

Significant gain in terms of median PFS (10 Months).

FDA approval in 2015 |

| PALOMA-2 |

Palbociclib + letrozole

vs.

letrozole alone |

ESR1+/HER2−advanced breast cancer |

27.6

vs.

14.5 |

Delayed ChT: 40.4

vs.

29.9 months |

| PALOMA-3 |

Palbociclib + fulvestrant

vs.

placebo + fulvestrant |

ESR1+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer after hormone therapy (30% received prior ChT) |

9.5 (11.2)

vs.

4.6 |

Significant gain in terms of median PFS |

| MONALEESA-2 |

Ribociclib + letrozole

vs.

letrozole alone |

Postmenopausal women with ESR1+/HER2 advanced breast cancer |

Not reached

vs.

14.7 |

FDA approval in 2017 |

| MONARCH-3 |

Abemaciclib + aromatase inhib.

vs.

placebo + aromatase inhib. |

Postmenopausal women with ESR1+/HER2 locoregionally recurrent or metastatic breast cancer with no prior systemic therapy |

28.1

vs.

14.7 |

Significantly prolonged PFSFDA approval in 2018 |

A metanalysis demonstrated that three CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors have similar efficacy when associated with AIs, and are superior to either fulvestrant or AI monotherapy independently of any stratification criteria, thus supporting AI plus CDK4 and CDK6 inhibition as the best approach in ESR1+/HER2− metastatic breast cancer [65,66].

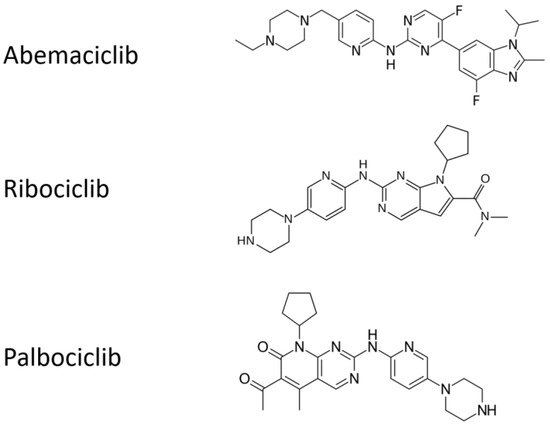

All the chemical structures of the molecules are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Chemical structures of cyclin inhibitors that are currently approved.

3.2. Real-Life Clinical Reports on Cyclin-D1/CDK4 and CDK6 Inhibitors, Including Association with Radiotherapy

Delivering unplanned RT (mainly with palliative/symptomatic aims) in advanced breast cancer patients on Cyclin-D1/CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors in prospective trials has produced empirically based treatment not supported by an appropriate rationale and consolidated approach, e g., in terms of RT intent, dose, and scheduling. However, several observational studies provided clearly suggest the lack of additive adverse events when palbociclib or ribociclib are combined with letrozole and concomitant palliative RT [73,74,75]. Additionally, a retrospective single-institution analysis suggested that 15 out a cohort of 42 pts with ESR1+ breast cancer with brain metastases showed promising results using CDK4 and CDK6 inhibitors palbociclib or abemaciclib for 6 months combined with stereotactic radiation [71] and only 5% of the patients developed radiation necrosis. However, only a slight improvement could be shown in survival. However, early radiation toxicities, including esophagitis and severe dermatitis have been reported in a breast cancer patient on palpociclib and palliative RT on cervical lymph nodes [72].

4. Molecular Grounds for Future Developments

4.1. CCND1 as a Target of Ionizing Radiation in the CCND1-CDK4, and CDK6 Complex

Only the CCND1-CDK4 and CDK6 complex has raised interest as a possible actionable target, whereas, in contrast, despite its prognostic relevance in cancer [

76], the regulatory member CCND1 per se has received less attention. As previously quoted, palpociclib induces autophagy in cancer, targeting CDK4 and CDK6 [

54,

55], via the LKB1 and Ser325 phosphorylation resulting in a CCND1-mediated, reduced activation of AMPK [

77]. The

CCND1 gene encoding CCND1 is activated in B-cell lymphomas and overexpressed in many other human cancers (esophageal, lung, breast, bladder carcinomas, etc.) where it acts as a proto-oncogene. Therefore, the CCND1 is a potential pivotal actionable target for cell cycle arrest. In normal cells, CCND1 has a very short life due to UPS degradation whereas in cancer cells, inhibition of turnover and increased levels of CCND1 were shown. Conversely, the knockdown of the activity of a specific deubiquitinase for CCND1 was shown, inducing growth suppression in cancer cells addicted to its expression [

78]. Ubiquitination of CCND1 is achievable in response to IR [

79] and, in cancer cells, IR or other DNA-damaging agents may activate selective autophagy [

54]. Autophagy shares common molecular mechanisms with UPS, with which it is intertwined in a close and complex relationship [

80]. As described by these authors, ubiquitin-specific recognition can have a pivotal role for CCND1 autophagy degradation. Selective autophagy requires some receptor proteins necessary for the process, such as p62 (also known as sequestosome 1 or SQSTM1), NBR1 (neighbor of the

BRCA 1 gene), CALCOCO2 (calcium binding and coiled-coil domain 2), and optineurin. p62 (the most relevant receptor protein for the subject dealt with here) is a component of several transduction signal cascades, such as Keap-Nrf2, and essential for UPS degradation.

Possible future strategies aimed at enhancing the IR-autophagic degradation of CCND1 in combination with drugs targeting the CCND1-CDK4 and CDK6 complex for G1/S arrest could overcome the IR-resistance of G1 and S phases of cell cycle

4.2. Ionizing Radiation, Autophagy Enhancement, and CCND1

Ionizing radiation can directly induce autophagy; although the mechanism underlying this effect has not been fully elucidated so far, two main mechanisms have been evoked: (1) similarly to rapamycin, IR reverts auto-phosphorylation of mTOR (e.g., in MCF-7 breast cancer cell culture) leading to the formation of autophagic vacuoles, segregation of cytoplasmic materials, and appearance of LC3 positivity and eventually mitochondrial hyperpolarization and decreased cell survival [

81].

(2) Radiation causes a protective pathway via endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, accumulation of ER misfolded proteins (unfolded protein response—UPR), and autophagy. Therefore, UPR pathway and autophagy are upregulated in some cancer types as an escape strategy leading to IR-activated autophagy responsible for resistance to RT [

82,

83,

84]. Nonetheless, autophagy is always depictable as a “double-edged sword”. As previously reviewed [

80], most of the literature dedicated to this subject is focused on drug manipulation of autophagy (i.e., either induction or inhibition) for improving IR-sensitivity in cancer cells, more than to IR in conditioning, per se, autophagy towards cell death.

Emphasis should be placed in autophagy during the cell cycle, as different studies have investigated the autophagy activation in the different phases of the cell cycle [

81,

82]. In contrast, other evidence suggests a protective suppression of autophagy during mitosis aimed at preventing the inappropriate inactivation of molecular species and organelles, functional for cellular replication, or even aggregated chromosomes [

50]. IR-based autophagy induced during the G1 and S counteracts the accelerated cell cycle in cancer and lays the groundwork for combined therapies combined with IR. It has been shown that

CCND1 suppresses autophagy in mammary epithelium [

85] whereas

CCND1 inhibits autophagy by activating AMPK in breast cancer cells [

77]. Further, in 2016, our group published a study in recurrent GB patients that prompted us to hypothesize a role for the IR-temozolomide treatment in inducing

CCND1 autophagic degradation in Beclin-1-positive GBs [

59]. Consistently, another group demonstrated the inverse correlation between low autophagic activity and high

CCND1 expression that were also related to poorer prognosis [

4]. In human and murine models of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC), induction of autophagy led to

CCND1 ubiquitination and its recruitment into autophagosomes via SQSTM1, formation of autophago-lysosomes, and degradation with suppression of tumor growth. Further, Chen et al. in 2019 [

58] showed that autophagy itself causes

CCND1 autophagic degradation in breast cancer cell lines with subsequent G1 cell cycle arrest underpinning the hypothesis of cell cycle modulation by CCND1 via mTORC1 signaling inhibition. Finally, we proposed in 2020 an overview of the role of autophagy, and namely its pivotal Beclin-1 protein, in

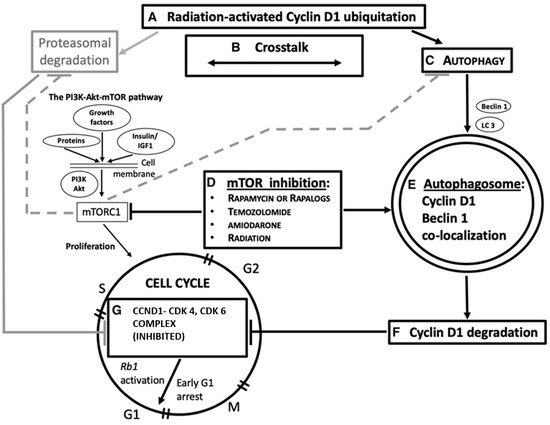

CCND1 degradation, as a possibly actionable mechanism for G1/S cell cycle arrest in cancer (

Figure 3) [

86].

Figure 3. A simplified overview of the role of autophagy and Beclin-1 in

CCND1 degradation, as a possible mechanism actionable for G 1/S cell cycle arrest in cancer. Radiation and chemotherapy are also considered in this domain. Some steps of the pathway are indicated, as shown in different tumors. A: Ubiquitation in

CCND1 levels is achievable by gamma irradiation [

3]. B: Ubiquitin–proteasome system and autophagy functionally cooperate with one another for protein homeostasis [

1]. C: Autophagy is induced in response to environmental stress resulting in abnormal or degraded proteins [

5]. Beclin-1 (encoded by the

BECN1 gene) is an autophagy protein, which has a critical role in the autophagy machinery. LC3 is a protein of the late autophagy pathway, necessary for autophagosome, biogenesis, and is used as an autophagy marker. D: Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors (everolimus [

2], rapamycin [

6,

11], amiodarone [

11]) activate autophagy, also concurrently with radiation or temozolomide chemotherapy [

6]. E: The autophagosome engulfs degraded proteins [

5], subsequently digested via its fusion with lysosomes.

CCND1 colocalizes with Beclin-1 in the cytoplasm [

7] after cancer therapy and this suggests its autophagy degradation. F and G:

CCND1 degradation deactivates the formation of the CCND1/CDK4 and CDK6 complex, thus activating the Rb1-dependent onco-suppressive pathway [

10] and hampering cell cycle progression [

2,

6]. In gray: an alternative pathway of

CCND1 degradation is through the ubiquitin–proteasome mechanism (UPD). Active mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) inhibits both UPD and autophagy (dashed lines). PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Image copyright © 2021, The American Physiological Society [

86].

It is still unclear whether autophagy could represent a true per se pro-death process, or can simply enhance the IR and chemotherapy sensitivity of cancer cells. The impact of autophagy in a cell death progress is cautiously named “autophagy-related cell death”. This definition is underpinned by the clinical observation that a high tissue expression of cytoplasmic Beclin-1 was related to better prognosis in patients with malignant glioma on temozolomide chemotherapy and radiotherapy [

87]. Notwithstanding, one should also take account of the tumor suppression of the autophagy-independent functions of Beclin-1 [

88].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22168391