Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

CYP2E1 is one of the fifty-seven cytochrome P450 genes in the human genome and is highly conserved. CYP2E1 is a unique P450 enzyme because its heme iron is constitutively in the high spin state, allowing direct reduction of, e.g., dioxygen, causing the formation of a variety of reactive oxygen species and reduction of xenobiotics to toxic products.

- NASH

- NAFLD

- liver

1. Introduction

Early studies of the metabolism of ethanol, independent of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), were performed using a mutant strain of deermouse (Peromyscus maniculatus) that is genetically deficient in low-Km ADH. Nonetheless, these mice were found to eliminate ethanol by a previously unidentified enzyme system. One of the enzyme candidates proposed was a cytochrome P450 active in ethanol oxidation in liver microsomes [1], which was also metabolized other short chain alcohols [2] and appeared to be inducible by ethanol treatment in animal models [3].

The exact mechanisms of P450-dependent ethanol oxidation were initially unclear but were associated with the production of reactive oxidative species (ROS), including hydroxyl radicals, which can indirectly oxidize ethanol [4,5]. The finding of an ethanol-dependent increase in P450-mediated oxidation [3,6] was important for the isolation of a specific form of ethanol inducible P450 and to understand the direct P450-mediated oxidation of ethanol. One such enzyme was purified from ethanol- and benzene-induced rabbits and from ethanol-treated rats [7,8]. This enzyme had the highest ethanol oxidation capacity of several different P450 forms isolated [7]. The corresponding cDNA was cloned in 1987 [9] and the enzyme was named cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) in 1991 [10].

2. Expression, Functions and Cellular Fate of CYP2E1

CYP2E1 is well conserved across mammalian species, indicating an important physiological function. In humans, the CYP2E1 gene has nine exons located on chromosome 10 and spans 11,413 base pairs [11]. Substantial inter-ethnic polymorphisms exist in CYP2E1. However, only very rare variants causing amino acid shifts have been described [12], and despite several epidemiological studies there is no clear evidence that any polymorphic variants have any functional relevance [13,14]. One recent study suggested a link between CYP2E1-333A > T and NASH, the authors showed increased inflammation and NASH in patient biopsies with the TA allele, largely mediated by a small increase in interferon-inducible protein 10 [15]. However, because only a relatively low number of patients were studied, much credence cannot be given to these findings unless they are reproduced independently. In liver, CYP2E1 is expressed mainly in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the hepatocytes, but is also found in the hepatic Kupffer cells [16,17,18]. Hepatic CYP2E1 is also present in the mitochondria, by translocation, following expression in the nuclear genome [19,20,21] and the plasma membrane [19,22,23,24]. However, the magnitude of induction of CYP2E1 in mitochondria is smaller than that of ER-resident CYP2E1.

CYP2E1 metabolizes a variety of small, hydrophobic substrates and drugs (reviewed in [13,14,21,25]). It is responsible for the metabolism of many toxic or carcinogenic chemicals, including chloroform and benzene, and drugs, such as paracetamol, salicylic acid and several inhalational anesthetics (e.g., isoflurane, sevoflurane and halothane). It therefore follows that conditions which elevate the expression of CYP2E1 can increase the damage caused by conversion of drugs to toxic intermediates [26]. The bioactivation of several pre-carcinogens by CYP2E1 has been discussed in relation to the development of cancers, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [27,28]. In addition, CYP2E1 metabolizes endogenous substances including acetone, acetol, steroids and polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as linoleic acid and arachidonic acid to generate ω-hydroxylated fatty acids [29,30,31,32]. CYP2E1 also metabolizes ethanol and other short chain alcohols, however its contribution to the overall ethanol clearance is low and P450-dependent alcohol metabolism does not influence overall ethanol clearance in rats [33]. Despite its importance as a metabolic enzyme the crystal structure and binding sites were only determined relatively recently, in 2008 [34,35].

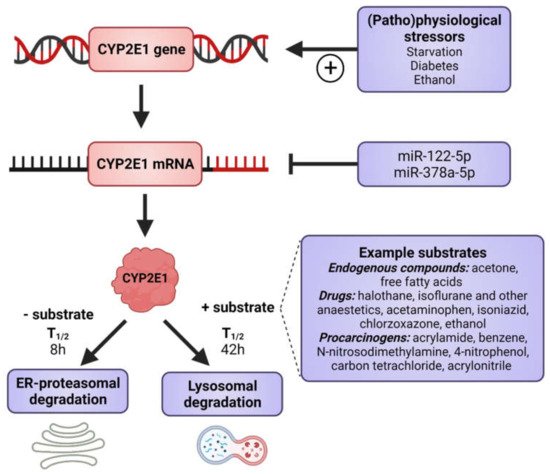

CYP2E1 is regulated by multiple, distinct mechanisms at the transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels (Figure 1) [36,37,38,39,40]. CYP2E1 expression is elevated in response to a variety of physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as starvation and uncontrolled diabetes, and also by ethanol, acetone and several other low molecular weight substrates [7,29,41,42,43,44,45]. However, it is primarily regulated at the post-transcriptional and post-translational levels [46]. Substrate-induced enzyme stabilization is the most important regulatory mechanism for CYP2E1 [47,48]; substrates and other chemicals binding to the substrate binding region stabilize the enzyme and prevent degradation by the proteasome-ER complex [38,48,49], involving the UBC7/gp78 and UbcH5a/CHIP E2-E3 ubiquitin ligases [50]. Thus, ER-mediated degradation is mainly active on CYP2E1 in the absence of substrates, whereas ligand-stabilized CYP2E1 is degraded more slowly by the autophagic-lysosomal pathway [51]. Due to its important physiological functions, the expression of CYP2E1 is under tight homeostatic control and multiple endogenous factors regulate CYP2E1 mRNA stability and protein expression including hormones (such as insulin, glucagon, growth hormone, adiponectin and leptin), growth factors (such as epidermal growth factor and hepatocyte growth factor) and various cytokines (reviewed in [40]).

Figure 1. Factors that induce CYP2E1 expressions. CYP2E1 can be induced by multiple mechanisms in transcriptional, post-transcriptional, translational, and post-translational levels. Some physiological and pathophysiological conditions, such as starvation and uncontrolled diabetes, increase CYP2E1 on the transcriptional level. Many hormones and cytokines regulate CYP2E1 on the mRNA and protein expression levels. Enzyme substrates stabilize the enzyme, preventing degradation by the ER proteasome and the enzyme degradation instead takes place via the autophagosome-lysosomal pathway. Figure made using BioRender.

As previously mentioned, the CYP2E1 gene is highly conserved and no functionally important genetic variants have been described. This indicates an important endogenous role, which is supported by our findings, wherein the knockdown of human CYP2E1 expression in the in vivo relevant three-dimensional (3D) liver spheroids [52] causes dramatic cell death in hepatocytes (unpublished observations from our lab). It is clear that CYP2E1 has important effects during catabolic conditions as the gene is transcriptionally induced during starvation [41]. The hepatic production of glucose is essential under starvation conditions with the primary supply of brain glucose, and about 10% of plasma glucose originating from acetone [53]. CYP2E1 readily oxidizes acetone to acetol [36], which is subsequently converted to pyruvate and then to glucose during gluconeogenesis. In addition, during conditions of starvation energy supply from fatty acids is essential and CYP2E1 is efficient in the ω-oxidation of fatty acids.

3. CYP2E1 in ALD

ALD is the most frequent liver disease in Europe, causing approximately 500,000 deaths per year, HCC resulting from pathological changes in the liver contributes highly to this death rate. There are strong genetic determinants in the development of ALD, e.g., PNPLA3, TM6SF2, and only approximately 10–20% of alcoholics develop cirrhosis of the liver [63].

ALD and NAFLD have several common mechanisms; generally, fibrosis occurs in response to enhanced ROS levels, lipid mediators and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, ALD and NAFLD are mechanistically similar and share histopathological features, particularly in terms of CYP2E1 induction and oxidative stress (reviewed in [64]). In addition, they share common genetic risk factors.

CYP2E1 is the most relevant CYP in ALD [65], it is highly inducible, has high catalytic activity for ethanol [25] and is prone to futile cycling in the absence of substrate to produce ROS [66]. CYP2E1 is regarded as a ‘leaky’ enzyme due to loose coupling of the CYP redox cycle, permitted by the constitutively high-spin state of the heme iron and, therefore, it has a great capacity to produce oxyradicals and initiate lipid peroxidation [67,68,69,70,71]. Thus, CYP2E1 may be important in mediating the effects of ethanol on ALD via increased lipid peroxidation [67].

In order to study the link between CYP2E1 and ALD, Morgan et al., generated CYP2E1 transgenic mice which exhibited increased serum ALT levels, higher histological scoring and ballooning hepatocytes with alcohol diet [72]. Using a transgenic mouse model expressing extra copies of human CYP2E1, Butura et al., showed increased liver injury and expression of stress related genes with alcohol diet [73]. Microarray analyses revealed that enhanced expression of structural genes, particularly cytokeratin 8 and 18, may be related to the observed pathology and they were suggested as biomarkers for ALD [73]. JunD, part of the transcription factor complex AP-1, was induced by CYP2E1 and alcohol, and its expression correlated with the degree of liver injury. This transcription factor complex is also linked to increased macrophage activation. Furthermore, JunD also has a role in hepatic stellate cell activation and regulates the cytokine interleukin 6 [73].

A second approach is to study CYP2E1 knockout mice in comparison to wild-type mice. Abdelmegeed et al., showed that that aged wild-type mice had increased hepatocyte vacuolation, ballooning, degeneration, and inflammatory cell infiltration compared with CYP2E1-null mice [74]. They also found that the aged wild-type mice had increased hepatocyte apoptosis, hepatic fibrosis, levels of hepatic hydrogen peroxide, lipid peroxidation, protein carbonylation, nitration and oxidative DNA damage, indicating an endogenous role for CYP2E1 for these events.

Another approach to study the influence of CYP2E1 on ALD involves the use of CYP2E1 inhibitors. Chlormethiazole is a specific CYP2E1 inhibitor [75] and has a pronounced inhibitory effect on ALD in the intra-gastric alcohol rat model [76]. Similar experiments were also conducted using diallyl sulfide and phenylethyl isothiocyanate as CYP2E1 inhibitors demonstrating a protective effect against hydroxyradical formation from ethanol and lipid peroxidation and inhibition of some pathological scores [77,78].

Together, these studies indicate a significant contribution of alcohol-dependent induction of CYP2E1 for the development of ALD [79]. The major cause is its ability to increase ROS formation after ethanol treatment, but other factors controlling the redox properties of the liver also contribute to the observed pathology.

Intestinal CYP2E1 in ALD

In addition to causing gut dysbiosis, alcohol increases CYP2E1 levels and nitroxidative stress in the intestinal epithelium similarly as in the liver [80,81,82,83,84]. This causes intestinal leakiness followed by increased circulating endotoxin levels [82,85,86,87]. Endotoxin can initiate a hepatic necroinflammatory cascade starting from increased levels of NF-κB and release of inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-α by Kupffer cells [85,88,89]. These results suggest a role of intestinal protein nitration in mediating alcohol-induced gut leakiness and subsequent hepatic injury in a CYP2E1-dependent manner. Even though fatty acids induce CYP2E1 in liver, as discussed later in this review, it is unclear whether this holds for intestinal CYP2E1 and increases gut leakiness playing a role in the development of NAFLD. NASH patients exhibit increased gut leakiness [90] and dysbiosis (reviewed in [91]) and gut inflammation and dysbiosis augments hepatic inflammation and fibrogenesis in mouse NASH models. However, the role of intestinal CYP2E1 and oxidative stress for gut leakiness was not tested [90,92,93]. It has been hypothesized that ethanol produced by microbiota fermenting dietary sugars could cause dysbiosis, increased CYP2E1 levels and nitroxidative stress in NAFLD patients (reviewed in [91]) and maybe endotoxin levels are thus lower in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis compared with non-alcoholic cirrhosis [87].

4. CYP2E1 in NAFLD

NAFLD has been known for over 40 years; despite this, the underlying mechanisms remain poorly understood [94]. NAFLD refers to a continuum of liver diseases beginning with non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), an accumulation of hepatic lipids not explained by alcohol consumption. In some cases, this can progress towards non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis and cirrhosis and eventually HCC. Most NAFLD patients are obese and exhibit mild systemic inflammation, which induces insulin resistance and plays a role in the mechanism of liver damage [95,96,97,98]. NASH encompasses varying degrees of liver injury and is now recognized as the hepatic component of metabolic syndrome [99,100,101,102].

Liver cirrhosis is part of alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and NASH, for which the only curative solution is often liver transplantation, and can progress to HCC in 3–4% of cases. The major causes of liver fibrosis are: hepatitis C infection (33%), alcohol (30%) and NASH (23%) [103]. The individual risks for liver cirrhosis caused by NASH and alcohol are largely determined by genetic risk factors, with polymorphisms in PNPLA3 and TM6SF2 and also MBOAT7, HSD17B13 and PCKS7 being the major common genetic determinants [104].

The multiple parallel hit model aims to explain the initiation and progression of NAFLD and has, in recent years, superseded the more simplistic two-hit model [101,105]. It suggests that multiple concurrent environmental and genetic insults, such as insulin resistance, oxidative stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, ER stress, endotoxin-induced TLR4-dependent release of inflammatory cytokines, and free fatty acid (FFA) accumulation combine to produce cell death and damage [106]. Oxidative stress mediated by ROS likely plays a primary role as the initiator of hepatic and extrahepatic damage and can cause damage in myriad ways by peroxidation of cellular macromolecules [107]. Oxidative stress can lead to lipid accumulation both directly and indirectly, most simplistically, ROS can peroxidate cellular lipids. Presence of these peroxidated lipids increases post-translational degradation of ApoB, preventing hepatocellular lipid export and leading to lipid accumulation. Alternatively, ROS can directly peroxidate proteins such as ApoB, directly preventing their function and producing a similar effect [108].

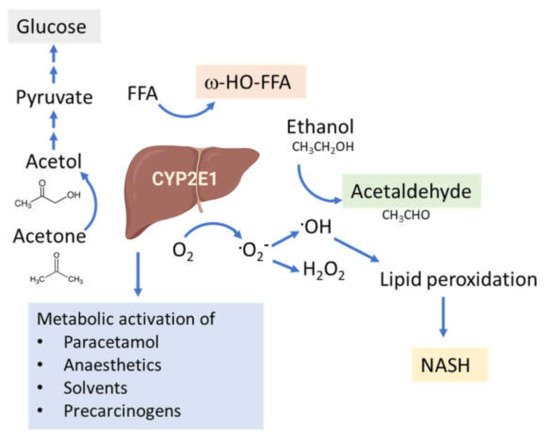

The connection between CYP2E1 and NASH was first suggested by Weltman et al., in 1996, where elevated levels of CYP2E1 were observed in steatosis and NASH patients, particularly in the centrilobular region [109] corresponding to the site of maximal hepatocellular injury in NASH [41,110]. This connection is based on the high propensity of CYP2E1 to generate ROS, even in the absence of substrates (Figure 2). In addition, CYP2E1 levels are elevated in obesity, steatosis and NASH in both humans and rodents [111,112,113].

Figure 2. Functions of the CYP2E1 enzyme. CYP2E1 has a role in normal physiological homeostasis by metabolizing endogenous and exogenous compounds. Major endogenous functions are ω-hydroxylation of FFA and oxidation of acetone to precursors of gluconeogenesis. Increased amounts of CYP2E1 results in increased lipid peroxidation and ROS production and is associated with the progression of NAFLD to NASH.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22158221

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!