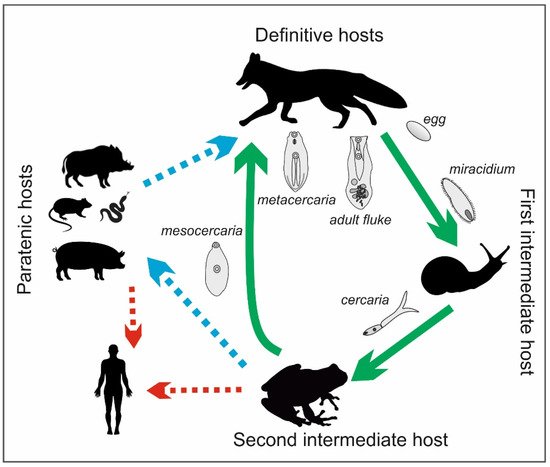

Humans may act as paratenic hosts; in some countries, depending on local dietary habits, they can be infected by eating frogs (frog legs) or any predators of frogs, among which the wild boar is the main source of infection [

67]. Frog-eating birds (herons, birds of prey, etc.) must also be taken into account as a source of human infection, even though these are not very popular dishes and are not normally consumed. There are also other sources of infection, but they are highly unlikely; these include Mustelidae (badgers, weasels, otters, etc.), Procyonidae (raccoons and coatis), which have been found to harbor the mesocercarial stage in their tissues, and even reptiles [

9,

14,

68]. The human hazards related to the consumption of meat products that contain mesocercariae of

A. alata depend on various factors, such as prior freezing of the meat, the amount of meat consumed, and the methods used in the processing of the meat [

57]. Freezing is recommended for inactivating many parasites, including

Trichinella or

Toxoplasma [

69]. Gonzales-Fuentes et al. (2015) pointed out that freezing game meat to an internal temperature of at most −13.7 °C inactivates mesocercariae [

70]. The survival of the larvae of

A. alata at the temperatures in refrigerators (4 to 8 °C) is very high, even during long-term storage; therefore, the potential risk for consumers remains high [

58]. To date, there is no precise information about the doses required for infections. However, after analyzing confirmed alariosis cases, it can be assumed that the severity of the symptoms is correlated with the number of larvae taken in [

62,

64,

65,

71]. According to current knowledge, heat treatment is the most effective method for the inactivation of

A. alata mesocercariae in wild boar meat. Heating at 72 °C for 2 min kills mesocercariae; therefore, the meat becomes fit for consumption [

72]. In the work of Portier et al. (2011), it was shown that

A. alata larvae could survive for at least five days when frozen (−18 °C) [

3]. The most effective method for killing these flukes—as in the case of

Trichinella spp.—is cooking at 71 °C [

38]. In addition, hygienic production is very important for minimizing the risks to consumers, as smear infections can occur during meat processing [

62,

64,

66,

71]. It is difficult to estimate the risk linked with the consumption of raw or undercooked meat products made from organic or free-range pigs. Studies conducted in Serbia on diaphragm samples collected from 72 free-range pigs showed that the percentage of samples infected with

A. alata mesocercariae was 2.77%. The researchers then underlined that the risk of human alariosis increases in regions where there is a tradition of making homemade pork products [

73]. In addition, in other countries, delicacies made from raw ground pork are very popular dishes. Among them, there are types of fresh sausages, such as Italian sausage, bratwurst, Polish steak tartare, and German

mett. These products are made from chopped, ground, or even pureed uncooked pork meat. In some territories, such as France and some Nordic countries, the consumption of game meat is related to the historical culture, in which this type of meat is shared among hunters and their families. Therefore, this group of consumers is especially exposed to the consumption of meat infected by

A. alata [

36,

58]. In 2014, in Germany, studies were performed to determine the survival rate of

A. alata larvae during the production of raw cured meat products, such as raw ham, salami, and raw sausage. These studies intended to clarify whether mesocercariae are eliminated during the production of these products and if traditional meat products play a role as sources of

A. alata infections in humans. In the experiment, the meats of wild boars and raccoons that were positive for the presence of

A. alata were used. A comparison of the three different technological processes showed that no live larvae were found in any of the ready-made hams, which proved that 100% of

A. alata mesocercariae were inactivated during production. However, 11.9% of salami sausages and 18.2% of the second type of raw sausage contained mesocercariae 24 h after preparation in the initial fermentation stage. Therefore, even tasting the meat during production may lead to an intake of

A. alata mesocercariae. These results indicate that the consumption of raw sausages in particular may be risky for consumers, especially if these products are consumed immediately after production [

74]. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR) conducted an evaluation to determine the risk of infection with parasites after consumption of game meat. This type of product is generally consumed in low amounts in Germany (200 to 400 g per person each year). However, the consumption of game meat in Germany has increased in recent years, and a certain group of people, including hunters, their relatives, and their friends, can consume 50–90 times more meals containing game each year [

75,

76,

77]. There is also an increasing interest in medium or rare game meat, which is pink at the core. The document mentioned above includes a recommendation to thoroughly cook game meat, raw game sausages, and raw meat products before consumption [

72].