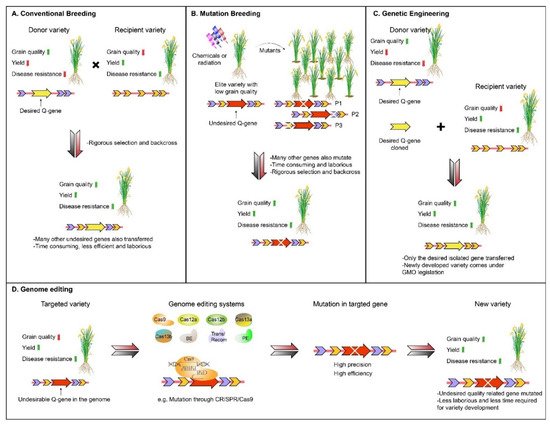

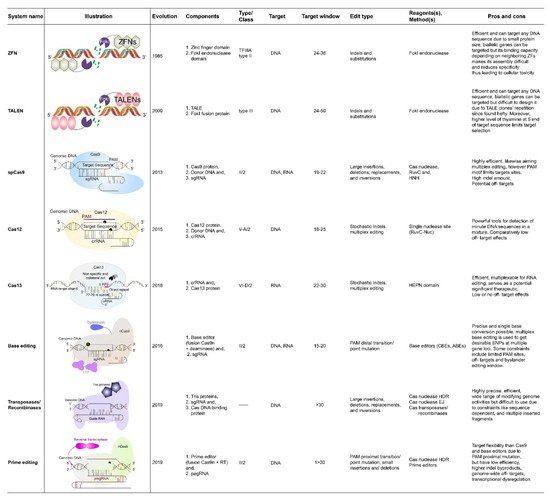

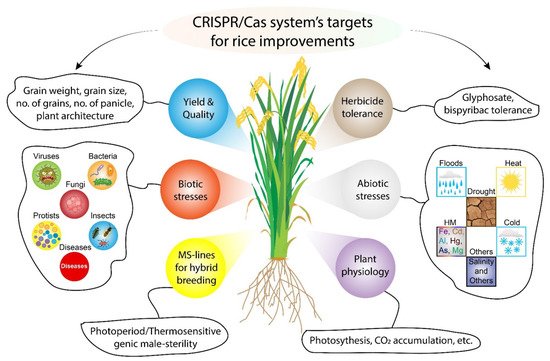

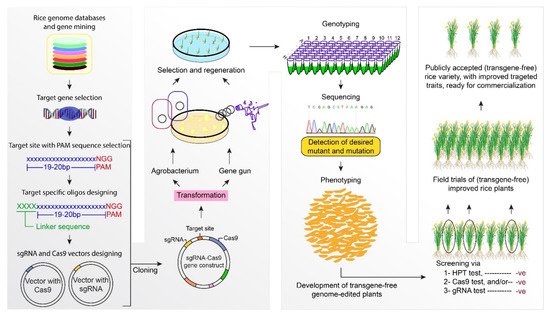

Food crop production and quality are two major attributes that ensure food security. Rice is one of the major sources of food that feeds half of the world’s population. Therefore, to feed about 10 billion people by 2050, there is a need to develop high-yielding grain quality of rice varieties, with greater pace. Although conventional and mutation breeding techniques have played a significant role in the development of desired varieties in the past, due to certain limitations, these techniques cannot fulfill the high demands for food in the present era. However, rice production and grain quality can be improved by employing new breeding techniques, such as genome editing tools (GETs), with high efficiency. These tools, including clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) systems, have revolutionized rice breeding. The protocol of CRISPR/Cas9 systems technology, and its variants, are the most reliable and efficient, and have been established in rice crops. New GETs, such as CRISPR/Cas12, and base editors, have also been applied to rice to improve it. Recombinases and prime editing tools have the potential to make edits more precisely and efficiently.

- rice

- grain yield

- abiotic stress

- biotic stress

- grain quality

- food security

- CRISPR/Cas systems

- base editing

- prime editing

1. Introduction

2. CRISPR/Cas9 Based Rice Crop Improvement

2.1. CRISPR/Cas9 for Improving Grain Yield of Rice

2.1.1. Improving the Plant Architecture

2.1.2. Improving the Panicle Architecture

| Targeted Trait | Targeted Gene/s | Cas9 Promoter/S | sgRNA Promoter/S | Improved Trait/s in Mutants | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant Architecture | SD1 | 2 × 35S pro | gRNA1SD1 gRNA3SE5 |

Grain yield, plant architecture, semi-dwarf plants, resistance to lodging | [28] |

| OsGA20ox2 | Pubi-H | OsU6a OsU6b | Grain yield, plant architecture, semi-dwarf plants, reduced gibberellins and flag leaf length | [30] | |

| SCM1/SD1, SCM3/OsTB1/FC1, SCM2/APO1 | 2 × 35S pro CaMV |

gRNA1, gRNA2, gRNA3, gRNA4, gRNA5, gRNA6 | Plant architecture, number of tillers, panicle architecture, larger panicles, stem cross-section area | [29] | |

| OsFWL4 | Maize Ubi1 | OsU6 | Grain yield, plant architecture, number of tillers, flag leaf area, grain length, number of cells in flag leaf | [32] | |

| IPA1 | Maize Ubi1 | U6a | Grain yield, plant architecture, number of tillers, reduced plant height | [31] | |

| Panicle Architecture | IPA1, GS3, DEP1, Gn1a | Maize Ubi1 | U6a | Grain yield, plant architecture, panicle architecture, number of tillers, grain size, dense erect panicles, grain number | [31] |

| GS3, OsGW2, Gn1a | p35S | OsU6 OsU3 |

Grain yield, grain size, grain weight, number of grains per panicle | [37] | |

| OsPIN5b, GS3 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H |

OsU6a | Grain yield, panicle architecture, panicle length, grain size | [33] | |

| GW2, 5 and 6 | pUBQ | OsU3, OsU6 TaU3 | Grain yield, grain weight | [36] | |

| OsSPL16/qGW8 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi |

OsU6a | Grain yield, grain weight, grain size | [38] | |

| Gn1a, GS3 | 2 × 35S pro | U3 | Grain yield, panicle architecture, number of grains per panicle, grain size | [35] | |

| Gn1a, DEP1 | 2 × 35S pro | OsU3 | Grain yield, panicle architecture, panicle orientation, number of grains per panicle | [34] | |

| Cytochrome P450, OsBADH2 | Pubi-H | U6a U6b U6c U3m |

Grain yield, grain size, aroma (2-acetyl-1-pyrroline (2AP) content) | [39] | |

| ABA Signaling Pathway | PYL1, PYL4, PYL6 | Maize Ubi1 | OsU6 OsU3 |

Number of grains, grain yield | [40] |

| OsPYL9 | PubiH | OsU6a OsU6b |

Grain yield under normal and limited water availability | [41] |

2.2. CRISPR/Cas9 for Abiotic Stress Tolerant Rice

| Stress | Edited Gene/S | Cas9 Promoter/S | sgRNA Promoter/S | Improved Traits in Mutants | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drought | OsSAPK2 | Pubi-H | U3 | Reduced drought, salinity, and osmotic stress tolerance; role of gene in ROS scavenging, stomatal conductance and ABA signaling | [45] |

| OsPYL9 | PubiH | OsU6a OsU6b |

Drought tolerance; grain yield, antioxidant activities, chlorophyll content, ABA accumulation, leaf cuticle wax, survival rate, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate | [41] | |

| OsERA1 | Not defined | pCAMBIA1300 | Drought tolerance, stomatal conductance, increased sensitivity to ABA. | [46] | |

| OsSRL1, OsSRL2 | Pubi-H | U6a U6b U6c U3m |

Improved drought tolerance; Reduced number of stomata, stomatal conductance, transpiration rate and malondialdehyde (MDA) content; Improved panicle number, abscisic acid (ABA) content, catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD) and survival rate | [47] | |

| DST | OsUBQ | OsU3 | Drought tolerance, leaf architecture, reduced stomatal density, enhanced leaf water retention | [48] | |

| OsmiR535 | UBI 35S pro |

OsU3 OsU6 |

Drought tolerance, ABA insensitivity, number of lateral roots (73% more), shoot length (30% longer), primary root length | [49] | |

| Salinity and Osmotic Stress | OsSAPK2 | Pubi-H | U3 | Reduced salinity and osmotic stress tolerance, role of gene in ROS scavenging | [45] |

| OsRR22 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H |

OsU6a | Salinity tolerance, shoot length, shoot fresh and dry weight | [50] | |

| DST | OsUBQ | OsU3 | Salinity tolerance, osmotic tolerance | [48] | |

| OsmiR535 | UBI 35S pro |

OsU3 OsU6 |

Salinity tolerance, osmotic tolerance, shoot length (86.8%), number of lateral roots (514% as compared with line overexpressing MIR535), primary root length (35.8%) | [49] | |

| Cold Stress | OsAnn3 | UBI 35S pro |

U3 | Response to cold tolerance | [51] |

| OsMYB30 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H |

OsU6a | Cold tolerance | [33] |

2.3. CRISPR/Cas9 for Improving Disease Resistance of Rice

| Pathogen | Improved Disease/Pathogen Resistance | Targeted Gene/S | Cas9 Promoter/S | sgRNA Promoter/S | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fungi | Rice blast (Magnaporthe oryzae) |

OsERF922 | 2 × 35S pro Pubi-H |

OsU6a | [60] |

| OsALB1, OsRSY1, | TrpC, TEF1 | SNR52, U6–1, U6-2 |

[61] | ||

| OsPi21 | PubiH | OsU6a, OsU3 | [62] | ||

| OsPi21 | PubiH | OsU6a, OsU6b | [63] | ||

| Bacteria | Bacterial leaf blight (Xanthomonas oryzae pv. Oryzae) |

OsSWEET14, OsSWEET11 | CaMV35S | U6 | [64] |

| OsSWEET11 or Os8N3 | 35S-p | OsU6a | [65] | ||

| OsXa13/SWEET11 | PubiH | OsU6a, OsU3 | [62] | ||

| OsSWEET11, OsSWEET13, OsSWEET14 | ZmUbiP | U6 | [55] | ||

| OsSWEET11, OsSWEET14 | 35S CaMV | SW11, SW14 | [56] | ||

| OsSWEET14 | Pubi or P35S | OsU3, OsU6b, OsU6c | [57] | ||

| OsSWEET14 | 35S, Ubi | OsU3 | [58] | ||

| OsXa13/ SWEET11 | 35S, Ubi | U3, U6a | [66] | ||

| Virus | Rice tungro spherical virus (RTSV) | eIF4G | ZmUBI1, CaMV35S |

TaU6 | [67] |

2.4. CRISPR/Cas9 for Herbicide Resistant Rice

2.5. CRISPR/Cas9 for Improving Rice Quality Parameters

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy11071359

References

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Wang, S.; Hong, Y.; Wang, Z. Rice and cold stress: Methods for its evaluation and summary of cold tolerance-related quantitative trait loci. Rice 2014, 7, 24.

- Zhao, M.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Improving nutritional quality of rice for human health. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020, 133, 1397–1413.

- Ray, D.K.; Mueller, N.D.; West, P.C.; Foley, J.A. Yield Trends Are Insufficient to Double Global Crop Production by 2050. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66428.

- Budak, H.; Hussain, B.; Khan, Z.; Ozturk, N.Z.; Ullah, N. From genetics to functional genomics: Improvement in drought signaling and tolerance in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 1–13.

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Samuel, C.; Fatai, A.; Magaji, U.; Kareem, I.; Kamarudin, Z.S.; Muhammad, I.; Kolapo, K. Drought Resistance in Rice from Conventional to Molecular Breeding: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3519.

- Ma, N.L.; Che Lah, W.A.; Abd. Kadir, N.; Mustaqim, M.; Rahmat, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Lam, S.D.; Ismail, M.R. Susceptibility and tolerance of rice crop to salt threat: Physiological and metabolic inspections. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192732.

- Hsu, P.D.; Lander, E.S.; Zhang, F. Development and Applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for Genome Engineering. Cell 2014, 157, 1262–1278.

- Jiang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Xie, W.; Long, T.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Q. Rice functional genomics research: Progress and implications for crop genetic improvement. Biotechnol. Adv. 2012, 30, 1059–1070.

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.; Cho, S.W.; Kim, J.-S. Targeted genome editing in human cells with zinc finger nucleases constructed via modular assembly. Genome Res. 2009, 19, 1279–1288.

- Cebrian-Serrano, A.; Davies, B. CRISPR-Cas orthologues and variants: Optimizing the repertoire, specificity and delivery of genome engineering tools. Mamm. Genome 2017, 28, 247–261.

- Naeem, M.; Majeed, S.; Hoque, M.Z.; Ahmad, I. Latest Developed Strategies to Minimize the Off-Target Effects in CRISPR-Cas-Mediated Genome Editing. Cells 2020, 9, 1608.

- Hussain, B.; Lucas, S.J.; Budak, H. CRISPR/Cas9 in plants: At play in the genome and at work for crop improvement. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2018, 17, 319–328.

- Adli, M. The CRISPR tool kit for genome editing and beyond. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1911.

- Zhang, Y.; Massel, K.; Godwin, I.D.; Gao, C. Applications and potential of genome editing in crop improvement. Genome Biol. 2018, 19, 210.

- Komor, A.C.; Kim, Y.B.; Packer, M.S.; Zuris, J.A.; Liu, D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature 2016, 533, 420–424.

- Hua, K.; Tao, X.; Yuan, F.; Wang, D.; Zhu, J.-K. Precise A·T to G·C Base Editing in the Rice Genome. Mol. Plant 2018, 11, 627–630.

- Hua, K.; Tao, X.; Liang, W.; Zhang, Z.; Gou, R.; Zhu, J. Simplified adenine base editors improve adenine base editing efficiency in rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 770–778.

- Shimatani, Z.; Kashojiya, S.; Takayama, M.; Terada, R.; Arazoe, T.; Ishii, H.; Teramura, H.; Yamamoto, T.; Komatsu, H.; Miura, K.; et al. Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion. Nat. Biotechnol. 2017, 35, 441–443.

- Lin, Q.; Zong, Y.; Xue, C.; Wang, S.; Jin, S.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Anzalone, A.V.; Raguram, A.; Doman, J.L.; et al. Prime genome editing in rice and wheat. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 582–585.

- Xu, W.; Zhang, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Kang, G.; He, X.; Song, J.; Yang, J. Versatile Nucleotides Substitution in Plant Using an Improved Prime Editing System. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 675–678.

- Tang, X.; Sretenovic, S.; Ren, Q.; Jia, X.; Li, M.; Fan, T.; Yin, D.; Xiang, S.; Guo, Y.; Liu, L.; et al. Plant Prime Editors Enable Precise Gene Editing in Rice Cells. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 667–670.

- Li, H.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Yan, L.; Xia, L. Precise Modifications of Both Exogenous and Endogenous Genes in Rice by Prime Editing. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 671–674.

- Hua, K.; Jiang, Y.; Tao, X.; Zhu, J. Precision genome engineering in rice using prime editing system. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 2167–2169.

- Hussain, B. Modernization in plant breeding approaches for improving biotic stress resistance in crop plants. Turkish J. Agric. For. 2015, 39, 515–530.

- Jiao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xue, D.; Wang, J.; Yan, M.; Liu, G.; Dong, G.; Zeng, D.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, X.; et al. Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat. Genet. 2010, 42, 541–544.

- Okada, S.; Sasaki, M.; Yamasaki, M. A novel Rice QTL qOPW11 Associated with Panicle Weight Affects Panicle and Plant Architecture. Rice 2018, 11, 53.

- Zhao, L.; Tan, L.; Zhu, Z.; Xiao, L.; Xie, D.; Sun, C. PAY 1 improves plant architecture and enhances grain yield in rice. Plant J. 2015, 83, 528–536.

- Hu, X.; Cui, Y.; Dong, G.; Feng, A.; Wang, D.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, J.; Zeng, D.; Guo, L.; et al. Using CRISPR-Cas9 to generate semi-dwarf rice lines in elite landraces. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19096.

- Cui, Y.; Hu, X.; Liang, G.; Feng, A.; Wang, F.; Ruan, S.; Dong, G.; Shen, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, D.; et al. Production of novel beneficial alleles of a rice yield-related QTL by CRISPR/Cas9. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 1987–1989.

- Han, Y.; Teng, K.; Nawaz, G.; Feng, X.; Usman, B.; Wang, X.; Luo, L.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Generation of semi-dwarf rice (Oryza sativa L.) lines by CRISPR/Cas9-directed mutagenesis of OsGA20ox2 and proteomic analysis of unveiled changes caused by mutations. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 387.

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, Z.; Wu, P.; Fang, M.; Pan, X.; Lin, Q.; Luo, W.; Wu, G.; Li, H. Reassessment of the Four Yield-related Genes Gn1a, DEP1, GS3, and IPA1 in Rice Using a CRISPR/Cas9 System. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 377.

- Gao, Q.; Li, G.; Sun, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, H.; Ji, J.; Wang, D.; Yuan, C.; Zhao, X. Targeted Mutagenesis of the Rice FW 2.2-Like Gene Family Using the CRISPR/Cas9 System Reveals OsFWL4 as a Regulator of Tiller Number and Plant Yield in Rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 809.

- Zeng, Y.; Wen, J.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Q.; Huang, W. Rational Improvement of Rice Yield and Cold Tolerance by Editing the Three Genes OsPIN5b, GS3, and OsMYB30 With the CRISPR–Cas9 System. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 10.

- Huang, L.; Zhang, R.; Huang, G.; Li, Y.; Melaku, G.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Developing superior alleles of yield genes in rice by artificial mutagenesis using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Crop J. 2018, 6, 475–481.

- Shen, L.; Wang, C.; Fu, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Yan, C.; Qian, Q.; Wang, K. QTL editing confers opposing yield performance in different rice varieties. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2018, 60, 89–93.

- Xu, R.; Yang, Y.; Qin, R.; Li, H.; Qiu, C.; Li, L.; Wei, P.; Yang, J. Rapid improvement of grain weight via highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-mediated multiplex genome editing in rice. J. Genet. Genom. 2016, 43, 529–532.

- Zhou, J.; Xin, X.; He, Y.; Chen, H.; Li, Q.; Tang, X.; Zhong, Z.; Deng, K.; Zheng, X.; Akher, S.A.; et al. Multiplex QTL editing of grain-related genes improves yield in elite rice varieties. Plant Cell Rep. 2019, 38, 475–485.

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liao, S.; Qin, B.; Liu, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Programmed editing of rice (Oryza sativa l.) osspl16 gene using crispr/cas9 improves grain yield by modulating the expression of pyruvate enzymes and cell cycle proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 249.

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Generation of High Yielding and Fragrant Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Lines by CRISPR/Cas9 Targeted Mutagenesis of Three Homoeologs of Cytochrome P450 Gene Family and OsBADH2 and Transcriptome and Proteome Profiling of Revealed Changes Triggered by Mutations. Plants 2020, 9, 788.

- Miao, C.; Xiao, L.; Hua, K.; Zou, C.; Zhao, Y.; Bressan, R.A.; Zhu, J.-K. Mutations in a subfamily of abscisic acid receptor genes promote rice growth and productivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 6058–6063.

- Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liao, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Precise Editing of the OsPYL9 Gene by RNA-Guided Cas9 Nuclease Confers Enhanced Drought Tolerance and Grain Yield in Rice (Oryza sativa L.) by Regulating Circadian Rhythm and Abiotic Stress Responsive Proteins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7854.

- Hussain, B.; KHAN, A.S.; Ali, Z. Genetic variation in wheat germplasm for salinity tolerance at seedling stage: Improved statistical inference. Turkish J. Agric. For. 2015, 39, 182–192.

- Hussain, B.; Lucas, S.J.; Ozturk, L.; Budak, H. Mapping QTLs conferring salt tolerance and micronutrient concentrations at seedling stagein wheat. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15662.

- Ahmad, S.; Sheng, Z.; Jalal, R.S.; Tabassum, J.; Ahmed, F.K.; Hu, S.; Shao, G.; Wei, X.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; Hu, P.; et al. CRISPR–Cas technology towards improvement of abiotic stress tolerance in plants. In CRISPR and RNAi Systems; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 755–772.

- Lou, D.; Wang, H.; Liang, G.; Yu, D. OsSAPK2 Confers Abscisic Acid Sensitivity and Tolerance to Drought Stress in Rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–15.

- Ogata, T.; Ishizaki, T.; Fujita, M.; Fujita, Y. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of OsERA1 confers enhanced responses to abscisic acid and drought stress and increased primary root growth under nonstressed conditions in rice. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0243376.

- Liao, S.; Qin, X.; Luo, L.; Han, Y.; Wang, X.; Usman, B.; Nawaz, G.; Zhao, N.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. CRISPR/Cas9-Induced Mutagenesis of Semi-Rolled Leaf1,2 Confers Curled Leaf Phenotype and Drought Tolerance by Influencing Protein Expression Patterns and ROS Scavenging in Rice (Oryza sativa L.). Agronomy 2019, 9, 728.

- Santosh Kumar, V.V.; Verma, R.K.; Yadav, S.K.; Yadav, P.; Watts, A.; Rao, M.V.; Chinnusamy, V. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing of drought and salt tolerance (OsDST) gene in indica mega rice cultivar MTU1010. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1099–1110.

- Yue, E.; Cao, H.; Liu, B. OsmiR535, a Potential Genetic Editing Target for Drought and Salinity Stress Tolerance in Oryza sativa. Plants 2020, 9, 1337.

- Zhang, A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, T.; Chen, Z.; Kong, D.; Bi, J.; Zhang, F.; Luo, X.; Wang, J.; et al. Enhanced rice salinity tolerance via CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the OsRR22 gene. Mol. Breed. 2019, 39, 47.

- Shen, C.; Que, Z.; Xia, Y.; Tang, N.; Li, D.; He, R.; Cao, M. Knock out of the annexin gene OsAnn3 via CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing decreased cold tolerance in rice. J. Plant Biol. 2017, 60, 539–547.

- Asibi, A.E.; Chai, Q.; Coulter, J.A. Rice Blast: A Disease with Implications for Global Food Security. Agronomy 2019, 9, 451.

- Pandolfi, V.; Neto, J.; Silva, M.; Amorim, L.; Wanderley-Nogueira, A.; Silva, R.; Kido, E.; Crovella, S.; Iseppon, A. Resistance (R) Genes: Applications and Prospects for Plant Biotechnology and Breeding. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2017, 18, 323–334.

- Hussain, B.; Akpınar, B.A.; Alaux, M.; Algharib, A.M.; Sehgal, D.; Ali, Z.; Appels7, R.; Aradottir, G.I.; Batley, J.; Bellec, A.; et al. Wheat genomics and breeding: Bridging the gap. Agrirxiv 2021, 1–57.

- Oliva, R.; Ji, C.; Atienza-Grande, G.; Huguet-Tapia, J.C.; Perez-Quintero, A.; Li, T.; Eom, J.-S.; Li, C.; Nguyen, H.; Liu, B.; et al. Broad-spectrum resistance to bacterial blight in rice using genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 1344–1350.

- Xu, Z.; Xu, X.; Gong, Q.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Ma, W.; Liu, L.; Zhu, B.; et al. Engineering Broad-Spectrum Bacterial Blight Resistance by Simultaneously Disrupting Variable TALE-Binding Elements of Multiple Susceptibility Genes in Rice. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1434–1446.

- Zeng, X.; Luo, Y.; Vu, N.T.Q.; Shen, S.; Xia, K.; Zhang, M. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mutation of OsSWEET14 in rice cv. Zhonghua11 confers resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae without yield penalty. BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 313.

- Zafar, K.; Khan, M.Z.; Amin, I.; Mukhtar, Z.; Yasmin, S.; Arif, M.; Ejaz, K.; Mansoor, S. Precise CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing in Super Basmati Rice for Resistance Against Bacterial Blight by Targeting the Major Susceptibility Gene. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11.

- Ahmad, S.; Wei, X.; Sheng, Z.; Hu, P.; Tang, S. CRISPR/Cas9 for development of disease resistance in plants: Recent progress, limitations and future prospects. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2020, 19, 26–39.

- Wang, F.; Wang, C.; Liu, P.; Lei, C.; Hao, W.; Gao, Y.; Liu, Y.G.; Zhao, K. Enhanced rice blast resistance by CRISPR/ Cas9-Targeted mutagenesis of the ERF transcription factor gene OsERF922. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154027.

- Foster, A.J.; Martin-Urdiroz, M.; Yan, X.; Wright, H.S.; Soanes, D.M.; Talbot, N.J. CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein-mediated co-editing and counterselection in the rice blast fungus. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14355.

- Li, S.; Shen, L.; Hu, P.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, X.; Qian, Q.; Wang, K.; Wang, Y. Developing disease-resistant thermosensitive male sterile rice by multiplex gene editing. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 61, 1201–1205.

- Nawaz, G.; Usman, B.; Peng, H.; Zhao, N.; Yuan, R.; Liu, Y.; Li, R. Knockout of Pi21 by CRISPR/Cas9 and iTRAQ-Based Proteomic Analysis of Mutants Revealed New Insights into M. oryzae Resistance in Elite Rice Line. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 735.

- Jiang, W.; Zhou, H.; Bi, H.; Fromm, M.; Yang, B.; Weeks, D.P. Demonstration of CRISPR/Cas9/sgRNA-mediated targeted gene modification in Arabidopsis, tobacco, sorghum and rice. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, e188.

- Kim, Y.-A.; Moon, H.; Park, C.-J. CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of Os8N3 in rice to confer resistance to Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae. Rice 2019, 12, 67.

- Li, C.; Li, W.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, H.; Xie, C.; Lin, Y. A new rice breeding method: CRISPR/Cas9 system editing of the Xa13 promoter to cultivate transgene-free bacterial blight-resistant rice. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 313–315.

- Macovei, A.; Sevilla, N.R.; Cantos, C.; Jonson, G.B.; Slamet-Loedin, I.; Čermák, T.; Voytas, D.F.; Choi, I.-R.; Chadha-Mohanty, P. Novel alleles of rice eIF4G generated by CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis confer resistance to Rice tungro spherical virus. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1918–1927.

- Sang, Y.; Mejuto, J.-C.; Xiao, J.; Simal-Gandara, J. Assessment of Glyphosate Impact on the Agrofood Ecosystem. Plants 2021, 10, 405.

- Hussain, B.; Mahmood, S. Development of transgenic cotton for combating biotic and abiotic stresses. In Cotton Production and Uses: Agronomy, Crop Protection, and Postharvest Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 527–545. ISBN 9789811514722.

- Shahzad, R.; Jamil, S.; Ahmad, S.; Nisar, A.; Amina, Z.; Saleem, S.; Zaffar Iqbal, M.; Muhammad Atif, R.; Wang, X. Harnessing the potential of plant transcription factors in developing climate resilient crops to improve global food security: Current and future perspectives. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2323–2341.

- Li, J.; Meng, X.; Zong, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Gao, C. Gene replacements and insertions in rice by intron targeting using CRISPR–Cas9. Nat. Plants 2016, 2, 16139.

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wu, C.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, H.; Guo, X.; Du, W.; Zhao, Y.; Xia, L. Engineering Herbicide-Resistant Rice Plants through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Homologous Recombination of Acetolactate Synthase. Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 628–631.

- Wang, F.; Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Fan, F.; Tao, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, Q.-H.; Yang, J. Creating a novel herbicide-tolerance OsALS allele using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing. Crop J. 2021, 9, 305–312.