Viral-associated respiratory infectious diseases are one of the most prominent subsets of respiratory failures, known as viral respiratory infections (VRI). VRIs are proceeded by an infection caused by viruses infecting the respiratory system. Due to their specific physical and biological properties, nanoparticles hold promising opportunities for both anti-viral treatments and vaccines against viral infections.

- viral infection

- SARS-CoV-2

- nanomedicine

- respiratory disease

- nano-vaccine

- COVID-19

1. Introduction

Viral infectious diseases and respiratory viral infections are among the most severe global health threats. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), millions of people are globally affected by viral diseases annually [1]. VRIs caused by different viral sources can infect the human upper and lower respiratory tracts, making the respiratory mucosa the primary gate of entry. Many viruses that could potentially lead to VARID have been reported in the current literature. Table 1 summarizes these viruses and their associated respiratory infectious disease. In this regard, SARS-CoV-2 and the influenza virus H1N1 are among the most recent to have caused global pandemics.

| Virus | VARID | Ref |

|---|---|---|

| Adenoviruses | Common Cold, Pneumonia | [15] |

| Coronaviruses | Common Cold, SARS, MERS, COVID-19 | [6] |

| Enteroviruses | Common Cold | [16] |

| Influenza Virus (Types A and B) | Influenza, Pneumonia | [17] |

| Metapneumovirus | Common Cold, Pneumonia, Bronchiolitis | [18] |

| Parainfluenza Virus (Type 3) | Common Cold, Croup, Pneumonia, Bronchiolitis | [19] |

| Parainfluenza Viruses (Types 1, 2) | Croup | [19] |

| Respiratory Syncytial viruses | Pneumonia, Bronchiolitis | [20] |

| Rhinoviruses | Common Cold | [21] |

2. Anti-Viral Responses of the Immune System in VARID and Evidence of Nanomedicine

2.1. Physical-Mucosal Barriers from Saliva to Bronchus-Associated Lymphoid Tissue

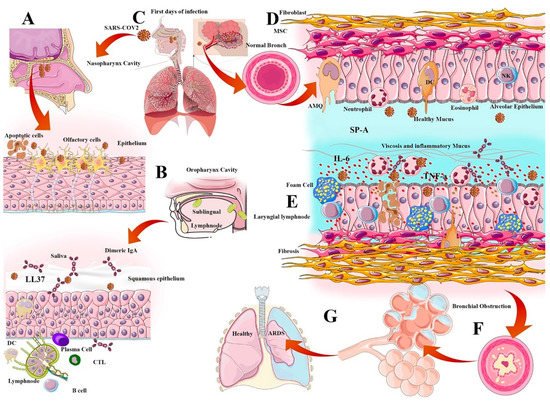

The physical-mucosal barriers from the oral and nasal cavities to the deepest regions of the lungs are considered the first line of defense in the innate immune system [22]. Alongside these physicochemical barriers, scattered lymphatic regions in the basal side of the respiratory tract (e.g., Nasal Associated Lymphoid Tissue (NALT) in the nasal cavities and mucosal associated lymphoid tissue in the mucosal layer of the respiratory tract) have a critical role in tropic anti-viral immunity responses [23].

The oral cavity is another physical barrier with enzyme-containing saliva and other NALT layers [26]. The contents of the saliva and nose mucosa in the respiratory tract determine the type of immune response. Given that the mouth and nose are the primary gateways for virus entry into the pulmonary tract, passing the virus through the saliva barrier, nasal mucosa, and ciliated layers of the upper respiratory tract can lead to acute viral infection in the lungs [27]. Some periodontal therapies using silver and gold nanoparticles can improve the immunity of the oral cavity and prevent the penetration of pathogens into the epithelium [28].

Saliva content, as an element of oral immunity, includes peptides, enzymes, and immune/epithelial cells-derived cytokines. Host defense peptides (HDP or antimicrobial peptides (AMP)) of the innate immune system, such as Cathelicidin (LL-37), α, β defensins, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and heterotypic salivary agglutinin (gp340, DMBT1) are secreted from the epithelial cells of the mouth, can consequently block the virus entry into epithelial cells or inhibit virus pathogenesis [29].

One of the most important AMPs in saliva and mucus is Cathelicidin (LL37); known for its antimicrobial role via lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding function, the anti-viral impacts were recently established in rhinoviruses and influenza [34,35,36]. Although saliva-derived HDPs and other antimicrobial elements might be used in the formulation of some nanoparticles, the saliva content can impact the fate of oral nanoparticles [37]. Nowadays, some nano-antibiotics have been developed, containing membrane-active human LL37 and synthetic compounds that mimic antimicrobial peptides, such as ceragenins [38].

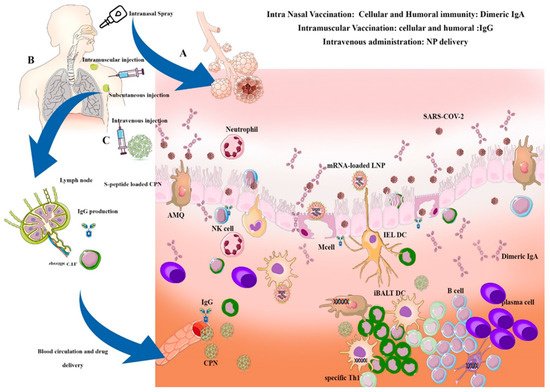

Alveolar macrophages (AMQ) are the most prevalent immune cells located in all parts of the respiratory tract. AMQs stabilize the hemostasis of the alveolar regions through rapid recognition of infections and activation of immune responses, such as DCs, T cells, and B cells. AMQ has an important immunomodulatory role in mucosal immunity and can cause the cytokine storm initiation via TNF-α, IFN-g, and IL-6 production, or cascade repair beginning through TGF-β and culminating in IDO release due to viral infection [48]. The pathogenesis of IL-6 and AMQs in alveolar thickness and fibrosis induction is important for immunopathogenesis in VARIDS, which is described in SARS-CoV-2 infection and illustrated in Figure 1.

2.2. Surfactant Role in Viral Infection

Pulmonary surfactant is a layer of phospho-lipoprotein compound secreted by Type 2 alveolar epithelial cells that cover the surface of the alveoli. This surfactant layer has amphipathic properties and traps water in the mucosal barrier to regulate the alveoli's size and tension. There are four important functions of surfactants in anti-viral immunity and homeostasis, including anti-viral immunity enhancement, inhibition of viral infectivity, inflammation regulation, and virus entry facilitating. The pulmonary surfactants are categorized into four subtypes (SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D) depending on their hydrophobic features and protein contents. Generally, SP-B and SP-C are more hydrophobic and smaller, while the anti-viral immunity of surfactants is more related to SP-A and SP-D. These compounds can bind to the viral glycoproteins and facilitate phagocytosis; the loss of SP-A would lead to delayed virus clearance. The amphipathic properties of these surfactants make them suitable candidates for anti-viral nanoparticle decoration [55].

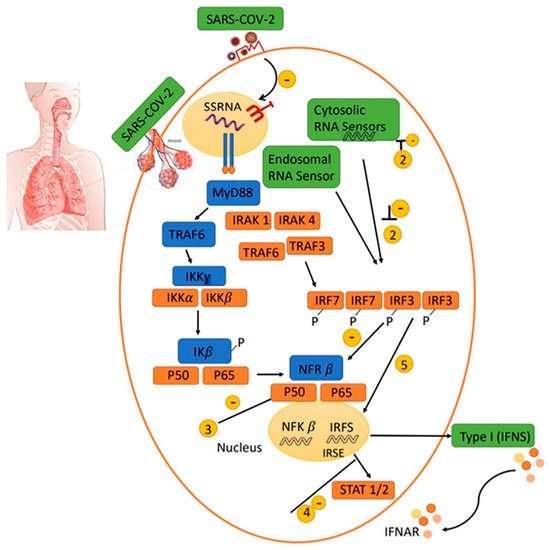

2.3. Antiviral IFN Route

It seems that either an appropriate underlying genetic background showing a specific anti-viral response or the utilization of anti-sera or PEGylated IFNα to stimulate the immune response is significant at the incubation stage in people infected with SARS-CoV-2. The response to Type I interferon in the patients with a poor prognosis has been significantly lower than that in the recovered patients during adaptive immune responses. When using a Type I IFN for treatment in a mouse model of SARS-CoV or MERS-CoV infection, the timing of administration is essential to obtain a protective response.

2.4. Natural and Secondary IgA

Dimeric IgA production can modulate the inflammation in the alveolar area and protect the respiratory epithelium from high inflammatory response-related damage. It occurs due to viral particles blocking and modulating the respiratory dysfunction, especially in chlamydia-dependent infections in neonates [65]. The uptake of IgA-loaded nanoparticles especially in chitin/chitosan nanoparticles within the nasal membranes following intranasal administration shows passive immunity in some respiratory diseases. Chitosan (CS) -dextran sulfate (DS) nanoparticles potentially increase the IgA-loaded combinations into nasal membranes and are widely used in intranasal formulations [66]. Some DNA vaccines have coupling capabilities with poly-lactide-co-glycolide (PLGA) and boost IgA production against the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in acute respiratory disease caused by RSV in children [67].

2.5. Cell-Mediated Immunity (CMI)

Cell-mediated immunity (CMI) is a specific immune response for the destruction of cells infected with viruses and subsequently protects the body against cancers, fungi, protozoa, and bacteria. Generally, virus-infected cells activate CMI, causing CD4 or T helper cells to affect the appearance of phagocytes, antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), and the secretion of various cytokines against the antigen. CTL activation is dependent on DC interactions and antigen presentation. In this regard, some polymeric nanoparticles such as PEI-coated PLGA NPs can stimulate the specific DC generation to stimulate specific anti-viral CTL [72].

3. Anti-Viral Systemic or Local Nano-Vaccination and Immunotherapy

Vaccination is a general strategy for the control of infectious diseases and is considered a significant choice for fighting viral diseases [74]. Due to several limitations (e.g., failure to trigger the immune system, potential of high toxicity, invasive administration, low in vivo stability, storage, and transport temperatures requirement), the clinical outcomes of some vaccines against different viral infections are not significant enough [75]. However, with emerging new formulations of vaccines (i.e., nano-vaccines), many of the shortcomings of conventional vaccination protocols are successfully addressed. Nano-vaccines can induce and enhance both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses in a more effective way than their former generations [76].

VARID nano-vaccines lead to a specific immune response using inactivated pathogens, attenuated virus, or subunit protein antigens. Examples of inactivated virus vaccine formulations for seasonal respiratory diseases, such as influenza include Influvac® [81], Vaxigrip® [82], and Fluzone® [83] against influenza Type A and Type B viruses. Examples of attenuated virus vaccine formulations include Nasovac® and Flumist® [84,85]. During the ongoing SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a significant number of vaccines have been designed using nanotechnologies such as Pfizer®, Moderna, NovaVax, Sinopharm, Sanofi–GSK, and others.

The most common strategies in viral respiratory vaccine solutions are to encapsulate antigens/epitopes within the nanoparticles to protect the structure of antigens from proteolytic degradation, as well as to deliver the antigen/epitopes to APCs and NALT. Another efficient reported strategy is the conjugation of antigens or epitopes on the surface of the polymer nanoparticles through which the viral behavior is mimicked [88,89,90].

The SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD) on S protein binds strongly to human and bat angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, resulting in specific humoral responses through RBD-specific antibodies secretion neutralization. This method has exciting potential for use in developing RBD-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infections [91].

In general, there are two types of vaccination methods in VARID: Systemic vaccination and intranasal vaccination. Alternatively, in intranasal vaccination, stable vaccines are formulated, such as mRNA loaded LNPs and are introduced to the nasal cavity through swaps or sprays.

Compared to conventional approaches, recent advances in vaccine nanomedicine offer superior therapeutic potential for viral respiratory diseases [94]. The unique features of the nanoparticles, including small particle size (100–200 nm), adjustable surface charge, and specific surfaces, resulting in a powerful platform for pharmaceutical applications and medicine.

3.1. Nanocarriers for Targeted Anti-Viral Drug Delivery and Nano-Vaccine Design

3.1.1. Liposomes

Liposomes are spherical shape lipid nanoparticles (20–200 nm) composed of a synthetic or natural phospholipid bilayer. Liposomes mimic cell membrane’s structure and can carry both hydrophilic and lipophilic pharmaceutics compounds [95]. The vesicle size of the liposomes for drug and vaccine delivery can have a significant role in triggering the immune activation process as soon as introducing to the body through the development of different pathways, such as Th1- or Th2 responses [98]. Additionally, they can stimulate the APCs uptake rate based on their size and surface charge. The surface charge of the liposomes can also have a giant effect on the rate of Ag loading efficacy through either entrapment or electrostatic adsorption methods [99].

3.1.2. Polymeric Nanoparticles

Polymeric nanoparticles (PNs) are another example of nanocarriers for anti-viral therapeutic delivery systems. PNs are generally composed of monomeric units in the form of a colloidal phase, categorized into synthetic polymers, natural polymers, and copolymers. Besides the application of polymeric nanostructures in the pharmaceutical industry, PNs have multiple advantages for vaccine delivery applications, including controlled release of antigens, intracellular persistence in APCs, and adjustable properties such as size, composition, and surface properties [104].

Commonly used polymeric nanoparticles for such applications are PLGA, poly-ε caprolactone (PCL), poly-(γ-glutamic acid) (γ-PGA), polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), poly-alkyl-cyanoacrylates, polyvinyl pyridine, polygluteraldehyde, polyacrylamides, polyethyleneimine (PEI), gelatin chitosan, and human serum albumin (HSA) [109]. Similar to liposomes, PNs are quickly taken up by the RES and Kupffer cells, with similar effects [110]. In one study, a poly (ethylene oxide)-modified poly (ε-caprolactone) (PEO-PCL) nanoparticulate system was developed for the encapsulation of saquinavir (SQV), an antiretroviral agent, using a solvent displacement process. THP-1 cells of the monocyte/macrophage origin demonstrated rapid cellular uptake of the encapsulated PEO-PCL nanoparticles. Intracellular SQV concentrations of the PEO-PCL-SQV nanoparticles were significantly higher than that of aqueous SQV solutions, indicating their benefits in viral therapy [111]. As previously mentioned, modified PEG is used in the final compound of both Pfizer® and Moderna® mRNA-based vaccines. NVX-CoV2373 (Novavax) is a protein-based vaccine containing saponin Matrix-M™ adjuvant [112]. With the use of polymeric nanoparticles, drug molecules are protected and both therapy and imaging can be combined [113,114]. Other promising characteristics of the polymeric nanoparticles such as biocompatibility [115], long-time spatiotemporal stability [116,117], and pathogen-like characteristics [118] make them a suitable candidate for intranasal vaccine administration [119].

3.1.3. Dendrimers

Dendrimers are a group of star-shaped three-dimensional macromolecular networks with some particular properties that make them a lucrative nanocarrier for anti-viral therapy. KK-46 dendrimer is a peptide-based compound used for intracellular delivery of anti-SARS-CoV-2 siRNA for inhibition of virus replication [131]. Finally, astrodimer sodium is a four-lysine dendrimer with a polyanionic charge that has been shown to inhibit viral infections in VeroE6 cells and reduce the replication of the virus [132].

3.1.4. Quantum Dots and Inorganic Nanoparticle

Quantum dots (QDs) are semiconductor inorganic nanocrystals with size-dependent optical and electronic properties and have been widely used for virus detection and imaging, given their inherent fluorescent emission [133]. QDs can also be used in viral replication inhibition approaches due to their inherent additional anti-viral capabilities.

3.1.5. SAPNs and VLPs

Self-assembling protein and peptide nanoparticles (SAPNs) are complexes made from monomeric protein oligomerization using recombinant technologies and are considered suitable candidates for pharmaceutical nanocarriers [150]. They can be formed in nano-diameter ranges and used as nano-vaccine candidates against viruses, making them suitable for intranasal delivery [150,151]. They can be designed to mimic viruses or bacteria in size and surface antigenicity and have been reported to elicit CD8+ T cell responses.

VLPs are another type of nano-vaccines that mimic the structure and the antigenic epitopes of their virus without including genetic material. They also promote efficient phagocytosis by APCs and immune response activation [157,158,159]. Today, ‘smart’ VLPs are often created using immunoinformatic strategies, the identification of epitopes, and artificially and genetically modifications. Construct design and viral vector engineering usually plays a very important role in this regard. Combining the VLPs with other nanoparticles is the basis of an effective vaccine [160].

4. Local Airway Delivery of Nanoparticles in VARID

4.1. Intranasal Airway Delivery of Therapeutic Nano-Carriers in VARID

Nanotechnology can potentially facilitate the efficacy of advanced therapeutics or vaccines by encapsulation inside the micro/nano-carriers to be administered using intranasal inhalation, as opposed to systematic delivery. In this way, Broichsitter et al. claimed that the anti-inflammatory corticosteroid Salbutamol could be effectively loaded in a polymeric nanocarrier composed of poly (vinyl sulfonate-co-vinyl alcohol)- graft-poly (D, L-lactide-co-glycolide, PLGA) for sustained pulmonary drug release [187]. To further enhance the selectivity of vaccine/drug delivery, the nanocarrier can be designed to have a targeted and smart release approach through stimuli-responsive delivery systems. As an example, the anti-inflammatory therapeutic hydroxy benzyl alcohol was incorporated into polyoxalate, which response to hydrogen peroxide. The drug incorporated polymer was then encapsulated inside PLGA nanoparticles. The results showed that the cleavage of peroxalate ester links between the drug and the polyoxalate polymer in the presence of hydrogen peroxide releases the drug to improve selectivity and environmental responsivity in drug delivery [188,189].

Other specific drugs, such as antibiotics can also be encapsulated inside nano-carriers to enhance the efficacy of therapy against bacterial lung infections through intranasal administration [190,191]. In the same way, the co-encapsulation of multiple antimicrobial agents can potentially improve the efficacy of the VARID treatment process [191].

Airway delivery of therapeutic nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) is also a practical approach for the treatment of side effect diseases caused by a viral infection.

Airway delivery of drug-loaded nano-carriers to the lungs and other parts of the respiratory tract could be performed by various methods such as nasal or oral spray, nebulization, dry powder inhaler devices or pressurized metered-dose inhalers [196].

In the case of SARS-CoV-2 as a type of VARID, various FDA-approved prescribed drugs have been evaluated for the treatment of infected patients [201,202,203,204]. However, despite considerable nanotechnology research and patent publications on various aspects of the coronavirus treatments [205,206], there is only one report on the utilization of nanotechnology-based design to address SARS-CoV-2 VARID using a localized airway delivery route. This nano-formulation of pharmaceutics design suggests the application of a previously developed nano-carrier based on chitosan (Novochizol™) for delivery of potential anti-COVID-19 drugs to the lungs [207]. Therefore, there is a remarkable capacity for the development of new drug formulations to prevent and/or treat the newly emerged SARS-CoV-2 virus, using nanotechnology enhanced airway delivery drugs through modulation of molecular targets or treatments of VARID. Aerosol liposomal therapy has also been used for several years with acceptable and safe clinical results [122,125], in terms of potential SARS-CoV-2 infection prevention and treatment, some reports claimed the efficiency of inhalation and oral use of a liposomal formulation of lactoferrin [124].

4.2. Intranasal Airway Delivery of Nano-Vaccines in VARID

Examples of intranasal vaccines against VARID are summarized in Table 3.

| Type of Nanoparticle | Main Material | Size (nm) | Target Respiratory Virus | Antigen/Epitope | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric | PLGA | 225 | Bovine parainfluenza 3 virus (BPI3V) |

BPI3V proteins | [121] |

| PLGA | 200–300 | Swine influenza virus (H1N2) | Inactivated virus H1N2 antigen | [122] | |

| γ-PGA | 100–200 | Influenza (H1N1) | Hemagglutinin | [123] | |

| Chitosan | 140 | Influenza (H1N1) | H1N1 antigen | [125] | |

| Chitosan | 300–350 | Influenza (H1N1) | HA-Split | [162] | |

| Chitosan | 572 | Swine influenza virus (H1N2) | Killed swine influenza antigen | [124] | |

| Chitosan | 200–250 | Influenza (H1N1) | M2e peptide | [164] | |

| HPMA/NIPAM | 12–25 | RSV | F protein | [165] | |

| PEG | 40–500 | RSV | F protein | [202] | |

| SA-CPH copolymer | 348–397 | RSV | Eα peptide | [208] | |

| CPH-CPTEG copolymer | - | RSV | F and G glycoproteins | [126] | |

| Self-assembled proteins and peptides (SANP) | Nucleocapsid (N) protein of RSV | 15 | RSV | RSV phosphoprotein | [167] |

| Nucleocapsid (N) protein of RSV | 15 | RSV | FsII epitope | [167] | |

| Nucleocapsid (N) protein of RSV | 15 | Influenza (H1N1) | M2e peptide | [168] | |

| Ferritin | 12.5 | Influenza (H1N1) | M2e peptide | [169] | |

| Influenza acid polymerase and the Q11 self-assembly domain | - | Influenza (H1N1) | Acid polymerase | [176] | |

| Inorganic | gold | 12 | Influenza (H1N1, H3N2, H5N1) | M2e peptide | [88] |

| VLP | - | - | Influenza (H1N1) | Hemagglutinin | [143] |

| - | 80–120 | Influenza (H1N1, H3N2, H5N1) | M2e5x peptide | [159] | |

| - | 60–80 | RSV | F protein et G glycoprotein of RSV and M1 protein of Influenza |

[171] | |

| Liposome | DLPC | 30–100 | Influenza (H1N1) | M2, HA, NP | [175] |

| Liposome, Polymer | 10:1:1:1 of DPPC, DPPG, Cholesterol (Chol), and DPPE-PEG2000 | 89 | SARS-COV 2 | S+ STING agonist | [209] |

| LNP | ChAdenovirus (S) | - | SARS-COV 2 | ChAd-S | [207] |