Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are chronic and ultimately fatal age-related lung diseases characterized by the progressive and irreversible accumulation of scar tissue in the lung parenchyma. Cellular senescence is defined as a cell fate decision caused by the accumulation of unrepairable cellular damage and is characterized by an abundant pro-inflammatory and pro-fibrotic secretome. The senescence response has been widely recognized as a beneficial physiological mechanism during development and in tumour suppression.

- pulmonary fibrosis

- senescence

- senolytics

- senomorphics

- aging

1. Introduction

The most prominent feature of lung fibrosis is a gradual age-related loss of function that occurs at the molecular, cellular, and tissue levels. The lack of somatic maintenance and repair functions and the stochastic enforcement of damage may explain the marked variability of cellular mechanisms that appear to be involved in aging phenotypes, such as lung fibrosis [3,4].

Fibrosis and wound healing are essentially interwoven processes, driven by a cascade of injury, inflammation, fibroblast proliferation and migration, matrix deposition and remodelling. Pathological fibrogenesis that occurs in many diverse organs and diseases is a dynamic process involving complex interactions between epithelial cells, fibroblasts, immune cells (macrophages, T-cells), and/or endothelial injuries [5,6]. There are many extrinsic hazards known to induce injury to lung epithelium—infections, exposures to organic or inorganic components, cigarette smoking, and so forth—while there is also damage of unknown aetiology. As a response to lung injury, many interrelated wound-healing pathways are activated in order to facilitate the repair, turnover, and adaptation of lung tissue [7]. However, although their aetiology and causative mechanisms varies, the different fibrotic lung diseases all fail to properly eliminate inciting factors, leading to continued tissue damaging with an abnormal and exaggerated accumulation of extracellular matrix (ECM) components and collagen deposition. Another hallmark of lung fibrosis is that older individuals display impaired ability to restore tissue homeostasis, heal wounds and resolve fibrosis, resulting in tissue scarring and irreversible organ damage [8]. In this regard, emerging studies highlight that one of the most important underlying mechanisms implicated in the pathobiology of age-related diseases such as pulmonary fibrosis is cellular senescence.

2. Aging and Cellular Senescence in Lung Fibrosis

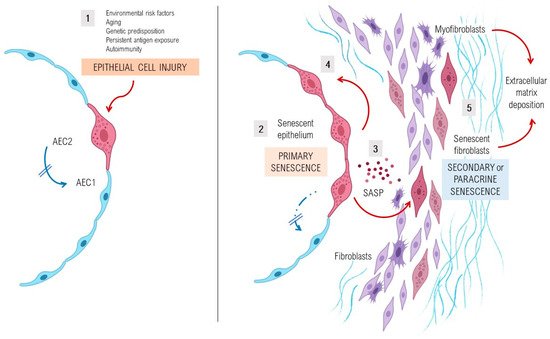

A complex interplay of environmental and genetic factors, age-related processes and epigenetic reprogramming leads to profound age-related cellular alterations in alveolar epithelial cells (AECs), immune cells, and fibroblasts from fibrotic lungs [28] (Figure 1). Evolutionary theories of the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis propose all the “hallmarks of aging” as major mechanisms of disease, including genomic instability, telomere attrition, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, deregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cellular senescence, stem cell exhaustion, and altered intercellular communication [14]. A growing body of evidence has provided a proof-of-concept that cellular senescence and the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) might be a key potential pathogenic phenotype, as they are associated with aging [29,30]. It has been shown that aged and diseased tissues of multiple multicellular organisms are more abundant in senescent cells [10,31,32]. Evidence provides support to the idea that senescent cells can fuel the hallmarks of a variety of aging phenotypes and overt age-related diseases, largely through the cell paracrine effects of the SASP [33]. Animal models with telomere deficiency in telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) have been shown to develop lung fibrosis with higher frequency after repeated low doses of bleomycin [44]. Moreover, growing body of evidence suggests that aging induces mitochondrial impairment in different cells associating metabolic changes, and has been shown to induce cellular senescence, a process called mitochondrial dysfunction-associated senescence [45].

3. Lung Susceptibility to Cellular Senescence

Under normal conditions, AEC2s can self-renew and differentiate into type I alveolar epithelial cells and therefore are considered as alveolar progenitor cells [47,48]. However, in age-related diseases such as lung fibrosis, a decrease of the renewal capacity and disfunction of distinct lung’s cell types, as well as AEC2s or lung fibroblasts, is a widely known phenomenon. Cellular senescence of AEC2s and lung fibroblasts of patients with IPF determine a cellular phenotype with the hyperactive secretion of a set of pro-fibrotic SASP’s cytokines, growth factors, angiostatic and procoagulant mediators, and proteases that promote an abnormal wound healing response [20,49,50]. Activated AEC2s express several mediators (platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor β1 [TGFβ1], tumour necrosis factor, osteopontin and CXC chemokine ligand 12, and endothelin-1), promoting profibrotic responses and inducing the migration of mesenchymal cells of different origins such as fibrocytes and resident fibroblasts [51]. Stress-induced senescent fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in the IPF lung secrete excessive amounts of ECM components, mainly fibrillar collagens and fibronectin, and are resistant to apoptosis, thus promoting the development of irreversible damage and lung fibrosis [49].

4. Pathological Impact of SASP in Fibrotic Lungs

Alterations in the secretome of senescent cells with a chronic increment of production of several inflammatory secretory proteins, including plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1), matrix remodelling proteins (MMPs), growth factors such as TGFβ1, as well as other initial inflammatory stimuli, including IL-6, IL-8 and IL-1α, are present in IPF lungs. The SASP of these cells also has the potential to induce ER stress and enhances senescence through autocrine activity, but also can promote adjacent healthy cells to undergo senescence through paracrine senescence. There is increasing evidence that paracrine effects of the molecular pathways that regulate SASP can be manipulated and several experimental drugs are being tested, however, most studies are now at early preclinical phases.

5. Aged Fibroblasts and Extracellular Matrix Changes

It has been shown that the senescent phenotype of IPF lung fibroblasts is associated with increased levels of senescent markers (p16Ink4a and p21) and positive β-gal staining. While p21 expression is driven by telomere shortening-induced p53 activity, p16Ink4a is upregulated by telomere-independent unknown mechanisms [70]. Activating caspase-8 moiety in the Ink-Attac (INK-linked apoptosis through targeted activation of caspase) suicide gene product, which is expressed only in p16-positive senescent cells, significantly improved health and lifespan after initiation of the combined therapy with dasatinib plus quercetin by promoting the clearance of senescent cells [71]. Navitoclax (ABT-263, a specific inhibitor of the anti-apoptotic proteins BCL-2 and BCL-xL), effectively cleared senescent cells in young p16-3MR exposed to sublethal doses of radiation that induced a significant increase in senescent cells [72]. Therefore, improvements in lifespan after clearance of senescent cells suggests that persistent cellular senescence may contribute to several age-related diseases, including pulmonary fibrosis. It also has been shown that in normally proliferating cells, such as human fibroblasts, there is a dynamic feedback loop in which the long-term activation of the checkpoint gene CDKN1A (p21) induces mitochondrial dysfunction and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which is considered necessary for the establishment of the senescent phenotype [73]. In fibroblasts from IPF patients, this process particularly affects redox balance, controlled by NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4) which has a crucial role in DNA damage, and is the key mediator of cellular antioxidant response NEF2-related factor 2. High expression of the NOX4 enzyme induces senescence in myofibroblasts by histone modifications and interferes with redox balance. It reduces reactive oxygen species, produces apoptosis of senescent myofibroblasts, and reverses established lung fibrosis in mice [8].

6. Loss of Epithelial Integrity

It has long been recognized that patients with sporadic or familial IPF present a dysfunctional alveolar epithelium associated with mutations and stress-induced senescence, which has a pivotal role in the aberrant lung injury-remodelling process. AEC2s in the IPF lungs express markers of senescence and apoptosis, which may indicate that the replacement of these cells might be a useful approach to attempting tissue repair and regeneration. It has been also proposed that stressed AEC2s in patients with lung fibrosis undergo an ineffective regeneration of the lung, so another pool of progenitor cells (KRT5+ Δp63+ cells) with persistent activation of the Notch signalling pathway mediates the repairment promoting micro-honeycombing rather than the regeneration of the normal alveoli epithelium [74].

A recent study demonstrated that although alveolar macrophages are long-lived lung-resident cells, changes in their number and transcriptional identity with age-related processes are not cell autonomous, although they instead might be shaped by interaction with the alveolar microenvironment independent of signalling in circulation [79]. Collectively, these findings suggest that strategies targeting the aging lung epithelial microenvironment may be crucial for restoring the alveolar macrophage-AECs axis function in aging.

7. Stem Cell Dysfunction

8. Conclusions

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22137012