The abnormal accumulation of Aβ in the brain, especially the oligomeric form, is an early feature of AD and is usually associated with neuronal loss, inflammatory responses, and oxidative stress [

4]. Recently, increasing evidence suggests a central role of the immune system in the progression or even the origin of AD [

5]. Many studies highlighted the role of neuroinflammation in the progression of AD, in which the release of inflammatory mediators can influence neuronal cells and their function [

6]. Indeed, the inflammatory response has a crucial role in different neurodegenerative diseases, and it is primarily driven by the microglia, which release cytokines causing chronic neuroinflammation [

6,

7]. Microglia originate from primitive macrophages and are the resident myeloid cells of the central nervous system (CNS). These cells not only check for pathogens and cell debris in the parenchyma of the CNS, but also support homeostasis and brain plasticity, being involved in the formation of neuronal connections during development [

8,

9,

10]. In physiological conditions, microglia play a critical role in several developmental events, as the formation of neural circuits, synaptic pruning, and remodeling, neurogenesis, clearing cellular debris, proteins aggregate, and pathogens [

3,

11,

12,

13]. Microglia are the non-neuronal CNS cells most closely related to changes observed in AD. Microglia remove by phagocytosis Aβ oligomers and protofibrils [

14]. Aβ oligomers propagate into the brain parenchyma, arousing a stronger microglial response and memory impairment than fibrils [

15]. Microglia immune response against Aβ oligomers in the hippocampus may be implicated in the pathogenesis of late-onset AD [

16]. However, impairment in this capacity may lead to an adverse increase of Aβ species in the CNS, which could then aggregate further into Aβ plaques. Moreover, Aβ peptide can bind to microglia’s receptors driving the production of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines [

17,

18]. Different studies have shown in AD mouse models that the increase of CD68, a marker for microglial activation, is associated with Aβ plaques [

19,

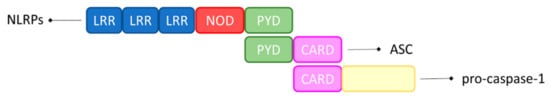

20]. Furthermore, the fibrillar form of Aβ can induce inflammasome activation in microglia, but less is known about the capacity of small Aβ oligomers and protofibrils, that seem to be more neurotoxic, to activate the inflammasome in microglia [

21,

22]. The extended exposure of microglia to Aβ can impair their function, decreasing phagocytosis and reducing the capacity to extend processes towards the lesioned tissue with the result that Aβ is inefficiently cleared from the neuronal tissue [

23,

24]. Different proinflammatory cytokines, like the tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF–α) or interleukin (IL)–1β, –6, –12 and –23, maintain a state of microglial activation and they could trigger each other, leading to a positive feedback loop which accelerates AD pathology [

25,

26,

27]. In particular, IL-1β induces IL-6, which is dramatically increased in AD patients [

28]. This last cytokine may have a crucial role in AD, indeed not only a mutation in the gene encoding for IL-6 may result in a late––onset disease, but it can also play a role in the synthesis and expression of amyloid precursor protein (APP) [

29]. Moreover, higher levels of IL-1β may affect tau hyperphosphorylation, and thus, aggravate AD pathology, impairing long term potentiation (LTP) and memory formation [

30]. In physiological conditions, microglia have a critical role in maintaining a healthy brain. Some structural variants of genes expressed on microglia and encoding for immune receptors, such as TREM2, CD33, and CR1, have been associated with a higher risk of AD [

31,

32,

33]. Moreover, altered gene expression in the regulation of the immune system in AD and its contribution to the pathology, support a pathogenic role of CNS–resident myeloid cells, like microglia, in the evolution of the disease [

34,

35]. Microglia dysfunction may occur not only by mutations, but also consequently to a long–lasting Aβ exposure [

36].