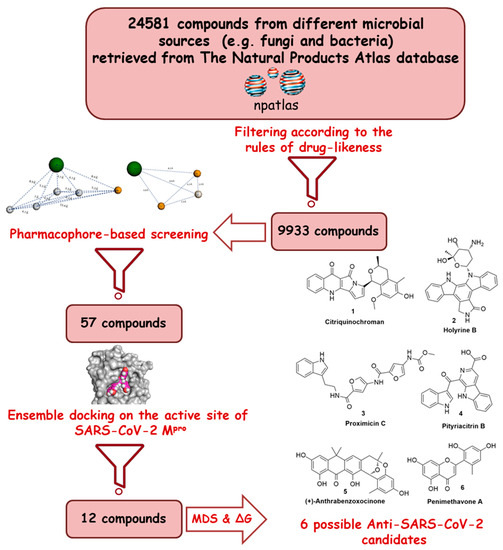

The main protease (Mpro) of the newly emerged severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was subjected to hyphenated pharmacophoric-based and structural-based virtual screenings using a library of microbial natural products (>24,000 compounds). Subsequent filtering of the resulted hits according to Lipinski’s rules was applied to select only the drug-like molecules. Top-scoring hits were further filtered out depending on their ability to show constant good binding affinities towards the molecular dynamic simulation (MDS)-derived enzyme’s conformers. Final MDS experiments were performed on the ligand-protein complexes to verify their binding modes and calculate their binding free energy. Consequently, a final selection of six compounds of microbial origin was proposed to possess high potential as anti-SARS-CoV-2 drug candidates. Our study provides insight into the role of the Mpro structural flexibility during interactions with the possible inhibitors and sheds light on the structure-based design of anti-coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) therapeutics targeting SARS-CoV-2

- Main protease,

- SARS-CoV-2

- COVID-19

- antiviral

- inhibitors

1. Definition

The viral genome is predominated by two open reading frames that are connected by a ribosomal frameshift site and encode the two replicase proteins, pp1a and pp1ab [7]. These polyproteins are cleaved by the viral main protease (Mpro), also called chymotrypsin-like protease, 3CLPro [8,9]. Mpro is considered a highly conserved molecular target across coronaviruses, and hence, it was designated as a potential target for anti-coronavirus drug development [10].

2. Introduction

3. Structure and Dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro

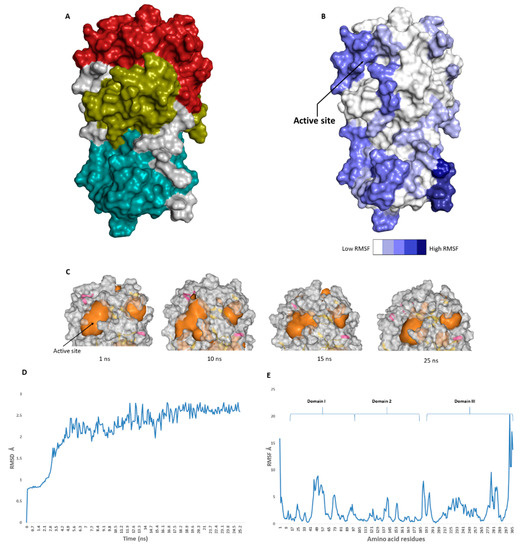

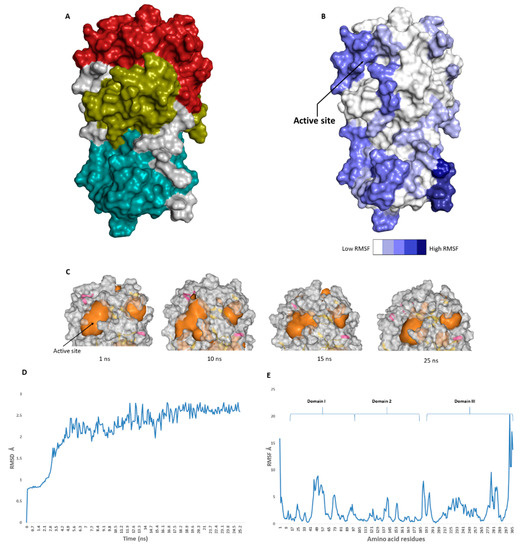

The catalytic site of the SARS-CoV-2 Mpro was found to be the largest cavity on the whole protein (static volume = 385.56 Å3) and is located in domains I and II (residues 11 to 99 and 100 to 182, respectively, Figure 2A). Additionally, it is smaller than the earlier SARS-CoV Mpro (static volume = 447.7 Å3) [35]. It is worth noting that the enzyme’s domain III, which consists of a globular cluster of five helices, is present only in coronaviruses and is responsible for the regulation of Mpro dimerization [36]. MDS of the reported SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB: 6LU7) [10] was performed to study the conformational changes in the active site using clustering analysis (conformation was sampled every 0.1 ns). The carbon alpha (Cα) root main square deviation (RMSD) values with respect to the initial structure were calculated for 25 ns of the simulation and were found to oscillate from 0.78 to 2.78 Å with a median value of (2.51 Å), reaching equilibrium (i.e., plateau) at 4.8 ns (Figure 2D). Regarding root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values, they demonstrated that Mpro had moderate flexibility (average RMSF = 2.43 Å, Figure 2E), where the active site showed the highest conformational changes (average RMSF = 3.1 Å), particularly at the THR-45 to ILE-59 loop (Figure 2B), which showed high fluctuations (i.e., RMSF values ranged from 5.2 to 8.9 Å, Figure 2E).

Figure 2. (A): The main domains (Mpro) in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Brick red: Domain I, Golden yellow: Domain II, Cyan: Domain III), (B): Heat-map illustrating the flexible regions on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, (C): The active site volume changes during the course of molecular dynamic simulation (MDS) (D and E): root main square deviation (RMSD) and root main square fluctuation (RMSF) of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro after 25 ns of MDS.

The volume of the active site was 399.56 Å3 at the beginning of the simulation (Figure 2C), and during the MDS, it gradually increased to reach 479.65 Å3 at 10 ns, and then began to decrease to reach 314.63 Å3 at the end of the MDS. Docking and virtual screening studies on such flexible catalytic active sites using only their crystalized static form would lead to poor prediction results. Hence, considering multiple structural conformations (i.e., ensemble docking) derived from the MDS study for our virtual screening in the present investigation could significantly improve the predicted results.

Figure 2. (A): The main domains (Mpro) in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (Brick red: Domain I, Golden yellow: Domain II, Cyan: Domain III), (B): Heat-map illustrating the flexible regions on SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, (C): The active site volume changes during the course of molecular dynamic simulation (MDS) (D and E): root main square deviation (RMSD) and root main square fluctuation (RMSF) of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro after 25 ns of MDS.

The volume of the active site was 399.56 Å3 at the beginning of the simulation (Figure 2C), and during the MDS, it gradually increased to reach 479.65 Å3 at 10 ns, and then began to decrease to reach 314.63 Å3 at the end of the MDS. Docking and virtual screening studies on such flexible catalytic active sites using only their crystalized static form would lead to poor prediction results. Hence, considering multiple structural conformations (i.e., ensemble docking) derived from the MDS study for our virtual screening in the present investigation could significantly improve the predicted results.

References

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Bayer, K.; Hentschel, U. Diversity, abundance and natural products of marine sponge-associated actinomycetes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caly, L.; Druce, J.D.; Catton, M.G.; Jans, D.A.; Wagstaff, K.M. The FDA-approved Drug Ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, N.; Basharat, Z.; Yousuf, M.; Castaldo, G.; Rastrelli, L.; Khan, H. Virtual Screening of Natural Products against Type II Transmembrane Serine Protease (TMPRSS2), the Priming Agent of Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Molecules 2020, 25, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, W.; Kumar, R.; Thompson, D.; Lyerly, W.; Moore, R.; Reid, T.E.; Lowe, H.; Toyang, N. Potential of Flavonoid-Inspired Phytomedicines against COVID-19. Molecules 2020, 25, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slynko, I.; Scharfe, M.; Rumpf, T.; Eib, J.; Metzger, E.; Schüle, R.; Jung, M.; Sippl, W. Virtual screening of PRK1 inhibitors: Ensemble docking, rescoring using binding free energy calculation and QSAR model development. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 2014, 54, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R.; Bayer, K.; Hentschel, U. Diversity, abundance and natural products of marine sponge-associated actinomycetes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caly, L.; Druce, J.D.; Catton, M.G.; Jans, D.A.; Wagstaff, K.M. The FDA-approved Drug Ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020, 104787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, N.; Basharat, Z.; Yousuf, M.; Castaldo, G.; Rastrelli, L.; Khan, H. Virtual Screening of Natural Products against Type II Transmembrane Serine Protease (TMPRSS2), the Priming Agent of Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Molecules 2020, 25, 2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngwa, W.; Kumar, R.; Thompson, D.; Lyerly, W.; Moore, R.; Reid, T.E.; Lowe, H.; Toyang, N. Potential of Flavonoid-Inspired Phytomedicines against COVID-19. Molecules 2020, 25, 2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slynko, I.; Scharfe, M.; Rumpf, T.; Eib, J.; Metzger, E.; Schüle, R.; Jung, M.; Sippl, W. Virtual screening of PRK1 inhibitors: Ensemble docking, rescoring using binding free energy calculation and QSAR model development. J. Chem. Inform. Model. 2014, 54, 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms8070970