The possibilities that serious games offer have been an area of increasing interest in recent years in the field of education. Unlike video games, which are created for entertainment purposes, serious games focus on the educational aspect in one of the possible developments that this type of software is capable of offering. The serious games recover characteristic elements of the free time of the students and take them to the classroom, generating an experience that favors learning.

- serious games

- academic achievement

1. Background

The presence of video games has progressively ousted other forms of entertainment. Data provided by the Spanish Video Game Association [1] show very high average weekly consumption figures: 6.7 h a week on average in Spain (in countries like the UK the figure almost doubles, with 11.6 h) and a male profile in 58% of the cases. This should be added to a larger presence in the lower age ranges: 75% of the boys and girls aged between 6 and 10 years fit this profile, thus reducing the percentage as we include higher ages. With these consumption levels, we find studies that point out the benefits of video games [2], also shared with serious games [3]. However, they are not exempt from possible negative assessments either. Research exists [4] showing that the use of video games during school days is related to a worse academic performance. Moreover, intensive video gamers have worse academic results in a research line that relates excess time dedicated to this type of leisure with problems in school performance [5], a situation occurring twice as often among boys than among girls [6].

However, the use of serious games offers an opportunity, because students showing difficulties working in ordinary situations at school increase their engagement in this type of proposals [7]. We do also have to be aware of possible improvements in learning processes, which are highly dependent on the contexts [8] and the design of the game experience [9]. The relation between motivation and learning benefits offers an opportunity to explore new proposals applied on teaching and learning.

The improvements produced by the use of serious games are summarized in three distinct types of engagement [10] related to behavior, affect and cognition. This explains the enormous impact that they usually have on the students’ motivation [11], which results in an improvement of the participation level and high engagement levels [12]. This strong link with software may help to understand the advantages in learning processes [13][14] and school curriculum [15].

2. Serious games and gender

Research work in the field of video games from a gender perspective is often found. In this sense, several studies have been carried out, dealing with the personality of boys and girls and the relation with the type of preferred video game [16] or how gender governs the interaction between cognitive and personal factors [17]. These works help to understand the relation between gender motivations that lead boys to spend more time playing [18]. Moreover, some works have shown that in the case of women, the relation between the type of game chosen and future fields of academic interest is stronger than in the case of men [19].

As opposed to the large volume of studies on gender and video games, there are only a few works focusing on this field in serious games. The analyzed studies show differences at social interaction level [20] and investigate differences in academic performance, concluding that in the case of girls it is, unexpectedly, as good as among boys, despite completing less missions and scoring worse in the game [21]. There are even studies according to which girls exceed boys in terms of commitment to the proposal and the learning level achieved [22][23], which is evidence of the concern of women to relate the proposed experience with the academic achievement [24]. These data apparently contradict some studies in which the teachers do state gender differences in the motivational capacity perceived in favor of boys [25]. Other works [26], although they do not find differences in performance, show differentiated styles: women collaborate and are more willing to accept experiences with serious games, while men are more competitive.

3. Serious Games and Mathematics

In primary education schools, serious games can help to improve the learning of the subjects, and, among them, the field of mathematics is a recurrent space of interest. It is also a place of research due to the gender gaps that affect achievements, attitudes and relationship with this field of knowledge [27]. Research shows that these gaps change based on cultural variations and opportunities for girls and women in aspects such as equity in school enrolment or women’s participation in research work [28]. However, at the primary education level there are no differences between boys and girls in mathematics performance, a situation that changes in favor of boys in secondary school and university [29]. What is identified in this type of content is that the gender difference in the performance in activities involving competitiveness among students is not the same as that produced in non-competitive tasks. This competitiveness, when it enters the picture, could be affecting the size of the gender gap in mathematics test scores, potentially exaggerating the mathematical advantage of men over women when learning is similar [30]. All of these elements globally influence the performance of boys and girls and explain, together with factors such as the socioeconomic level, the significant differences shown in international studies for the Spanish context compared to other countries [31].

One way to see the progress in the first levels of primary education in mathematics is through the concept of mathematical fluency [32]. The measure of this element can work as a good indicator of school improvement with the use of serious games. Recent research relates the use of serious games with the improvement of mathematical fluency [33], being also a benefit that is projected in the set of key learning in schools [34].

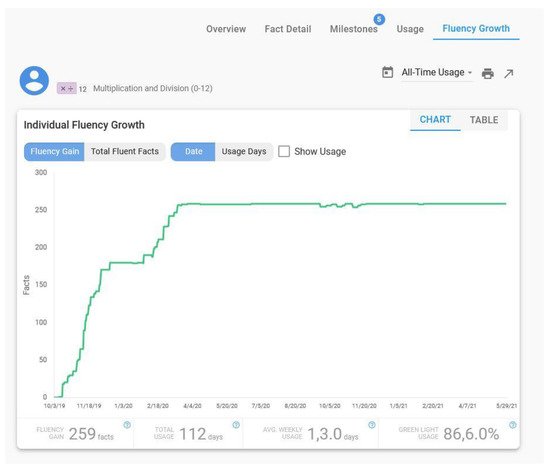

In order to probe into the possible improvements in mathematical fluency due to the use of serious games, we have recently carried out an investigation in this area with the ReflexMath software. It is a program frequently used in schools in the United States that focuses on the mathematical fluency of calculus (Figure 1) with a curricular structure that follows the indications of the Council of Chief State School [35]. The software generates fully individualized learning pathways from the massive collection of user data, mainly based on response times and the error rate. A virtual assistant, in the form of a child character, provides help when the calculation processes do not improve. In serious games, the activation of the assistant is based on the error, considering it an opportunity for learning and not a penalty. This character, following the indicated curricular proposal, offers specific strategies for the calculation operation detected as especially difficult for students. The work of systematizing the calculation is based on video games in which the user’s interaction with the characters and the proposed situations is achieved by solving calculation operations adapted in real time to their profile. The software, in addition to the serious game, has an integrated gamification system generating rewards through exchangeable points for improvements to the game’s avatar, awards in the form of diplomas, etc. similar to a microform of digital badging. Teachers have the possibility of monitoring the process through a specific dashboard that offers information through tools based on learning analytics (Figure 2).

Figura 1. A game in ReflexMath software.

Figura 2. Teacher dashboard.

The data from the research carried out with this software in a primary education center show that, in a context such as Spain and with a curriculum structured differently from the American one, this software leads to great improvements in mathematical fluency in schools with ordinary schooling students in the first four levels of primary education with a statistically significant and large improvement in mathematical fluency. The data are consistent with previous studies with the same software with much smaller samples [36] and also with students with learning difficulties [37].

However, surprisingly, the performance differences shown in the gender-segmented pretest are very favorable for boys. The pretest data also reproduced that, with the methodology used in the school, these differences did not decrease over the years. In addition, it was an aspect in which the educational center of the study showed concern because it had never been evaluated and there was no knowledge of this fact. It is an emerging element that requires analysis and that could potentially be worked on through an alternative methodology through serious play.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13126586

References

- AEVI La Industria Del Videojuego En España. Anuario 2019. Available online: (accessed on 10 October 2020).

- Granic, I.; Lobel, A.; Engels, R.C.M.E. The Benefits of Playing Video Games. Am. Psychol. 2014, 69, 66–78.

- Connolly, T.M.; Boyle, E.A.; MacArthur, E.; Hainey, T.; Boyle, J.M. A Systematic Literature Review of Empirical Evidence on Computer Games and Serious Games. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 661–686.

- Gómez-Gonzalvo, F.; Devís-Devís, J.; Molina-Alventosa, P. El tiempo de uso de los videojuegos en el rendimiento académico de los adolescentes. Comun. Rev. Científica Comun. Educ. 2020, 28, 89–99.

- Lemmens, J.S.; Hendriks, S.J.F. Addictive Online Games: Examining the Relationship Between Game Genres and Internet Gaming Disorder. Cyberpsychology Behav. Soc. Netw. 2016, 19, 270–276.

- Greenberg, B.S.; Sherry, J.; Lachlan, K.; Lucas, K.; Holmstrom, A. Orientations to Video Games Among Gender and Age Groups. Simul. Gaming 2010, 41, 238–259.

- Mahmoudi, H.; Koushafar, M.; Saribagloo, J.; Pashavi, G. The Effect of Computer Games on Speed, Attention and Consistency of Learning Mathematics among Students. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 176, 419–424.

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does Gamification Work?—A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034.

- Pourabdollahian, B.; Taisch, M.; Kerga, E. Serious Games in Manufacturing Education: Evaluation of Learners’ Engagement. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2012, 15, 256–265.

- Hookham, G.; Nesbitt, K. A Systematic Review of the Definition and Measurement of Engagement in Serious Games. In Proceedings of the Australasian Computer Science Week Multiconference, Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 29 January 2019; pp. 1–10.

- Filella, G.; Pérez-Escoda, N.; Ros-Morente, A. Evaluación Del Programa de Educación Emocional “Happy 8-12” Para La Resolución Asertiva de Los Conflictos Entre Iguales. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 14, 582–601.

- Wrzesien, M.; Alcañiz Raya, M. Learning in Serious Virtual Worlds: Evaluation of Learning Effectiveness and Appeal to Students in the E-Junior Project. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 178–187.

- Clark, D.B.; Tanner-Smith, E.E.; Killingsworth, S.S. Digital Games, Design, and Learning: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 2016.

- Wouters, P.; van Nimwegen, C.; van Oostendorp, H.; van der Spek, E.D. A Meta-Analysis of the Cognitive and Motivational Effects of Serious Games. J. Educ. Psychol. 2013, 105, 249–265.

- de Carvalho, C.V.; Rodríguez, M.C.; Nistal, M.L.; Hromin, M.; Bianchi, A.; Heidmann, O.; Tsalapatas, H.; Metin, A. Using Video Games to Promote Engineering Careers. Int. J. Eng. Educ. 2018, 34, 388–399.

- Homer, B.D.; Hayward, E.O.; Frye, J.; Plass, J.L. Gender and Player Characteristics in Video Game Play of Preadolescents. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012, 28, 1782–1789.

- Liu, C.-C. Understanding Player Behavior in Online Games: The Role of Gender. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 111, 265–274.

- Brooks, F.M.; Chester, K.L.; Smeeton, N.C.; Spencer, N.H. Video Gaming in Adolescence: Factors Associated with Leisure Time Use. J. Youth Stud. 2016, 19, 36–54.

- Giammarco, E.A.; Schneider, T.J.; Carswell, J.J.; Knipe, W.S. Video Game Preferences and Their Relation to Career Interests. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2015, 73, 98–104.

- Mansour, S.; El-Said, M. The Relationship between Educational Serious Games, Gender, and Students’ Social Interaction. WSEAS Trans. Comput. 2008, 7, 640–649.

- Nietfeld, J.L. Predicting Transfer from a Game-Based Learning Environment. Comput. Educ. 2020, 146, 103780.

- Khan, A.; Ahmad, F.H.; Malik, M.M. Use of Digital Game Based Learning and Gamification in Secondary School Science: The Effect on Student Engagement, Learning and Gender Difference. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2017, 22, 2767–2804.

- Zhao, D.; Muntean, C.H.; Chis, A.E.; Muntean, G.-M. Learner Attitude, Educational Background, and Gender Influence on Knowledge Gain in a Serious Games-Enhanced Programming Course. IEEE Trans. Educ. 2021, 1–9.

- Vate-U-Lan, P. Oxymoron of Serious Games in ELearning: Gender Differences from an Internet-Based Survey in Thailand; Czech Technical University in Prague: Budapest, Hungary, 2017; pp. 6–17.

- Passarelli, M.; Dagnino, F.; Earp, J.; Manganello, F.; Persico, D.; Pozzi, F.; Bailey, C.; Perrotta, C.; Buijtenweg, T.; Haggis, M. Educational Games as a Motivational Tool: Considerations on Their Potential and Limitations; SciTePress: Heraklion, Greece, 2021; pp. 330–337.

- Garber, L.L.; Hyatt, E.M.; Boya, Ü.Ö. Gender Differences in Learning Preferences among Participants of Serious Business Games. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2017, 15, 11–29.

- Alordiah, C.O.; Akpadaka, G.; Oviogbodu, C.O. The Influence of Gender, School Location and Socio-Economic Status on Students’ Academic Achievement in Mathematics. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 130–136.

- Else-Quest, N.M.; Hyde, J.S.; Linn, M.C. Cross-National Patterns of Gender Differences in Mathematics: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 136, 103–127.

- Hyde, J.S.; Fennema, E.; Lamon, S.J. Gender Differences in Mathematics Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Psychol. Bull. 1990, 107, 139–155.

- Niederle, M.; Vesterlund, L. Explaining the Gender Gap in Math Test Scores: The Role of Competition. J. Econ. Perspect. 2010, 24, 129–144.

- TIMMS Estudio Internacional de Tendencias En Matemáticas y Ciencias. Informe Español. Available online: (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Baroody, A.J.; Eiland, M.D.; Purpura, D.J.; Reid, E.E. Can Computer-Assisted Discovery Learning Foster First Graders’ Fluency with the Most Basic Addition Combinations? Am. Educ. Res. J. 2013, 50, 533–573.

- van der Ven, F.; Segers, E.; Takashima, A.; Verhoeven, L. Effects of a Tablet Game Intervention on Simple Addition and Subtraction Fluency in First Graders. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 200–207.

- Geary, D.C. Cognitive Predictors of Achievement Growth in Mathematics: A 5-Year Longitudinal Study. Dev. Psychol. 2011, 47, 1539–1552.

- Council of Chief State School Officers Common Core State Standards Initiative. Preparing America’s Students for College & Career. Available online: (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Cozad, L. Effects of a Digital Mathematics Fluency Program on the Fluency and Generalization of Learners; The Pennsylvania State University: Centre, PA, USA, 2019.

- Sarrell, D. The Effects of Reflex Math as a Response to Intervention Strategy to Improve Math Automaticity among Male and Female At-Risk Middle School Students; Liberty University: Lynchburg, VA, USA, 2014.