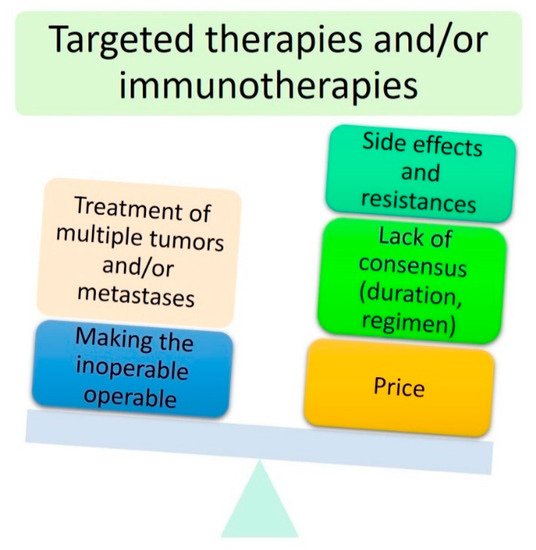

The management of periocular skin malignant tumours is challenging. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for localised eyelid cancers. For more locally advanced cancers, especially those invading the orbit, orbital exenteration has long been considered the gold standard; however, it is a highly disfiguring and traumatic surgery. The last two decades have been marked by the emergence of a new paradigm shift towards the use of ‘eye-sparing’ strategies. In the early 2000s, the first step consisted of performing wide conservative eyelid and orbital excisions. Multiple flaps and grafts were needed, as well as adjuvant radiotherapy in selected cases. Although being incredibly attractive, several limitations such as the inability to treat the more posteriorly located orbital lesions, as well as unbearable diplopia, eye pain and even secondary eye loss were identified. Therefore, surgeons should distinguish ‘eye-sparing’ from ‘sight-sparing’ strategies. The second step emerged over the last decade and was based on the development of targeted therapies and immunotherapies. Their advantages include their potential ability to treat almost all tumours, regardless of their locations, without performing complex surgeries. However, several limitations have been reported, including their side effects, the appearance of primary or secondary resistances, their price and the lack of consensus on treatment regimen and exact duration.

1. Introduction

The eyelids are considered a high-risk skin malignancy area. Managing periocular tumours is challenging for functional and cosmetic reasons. Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common eyelid cancer, followed by squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), melanoma, sebaceous carcinoma and Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) [

1]. Surgery remains the mainstay of treatment for localised tumours, with the aim of obtaining clear surgical margins. Tumours originating from the internal or external canthus are at particular risk of orbital invasion [

2,

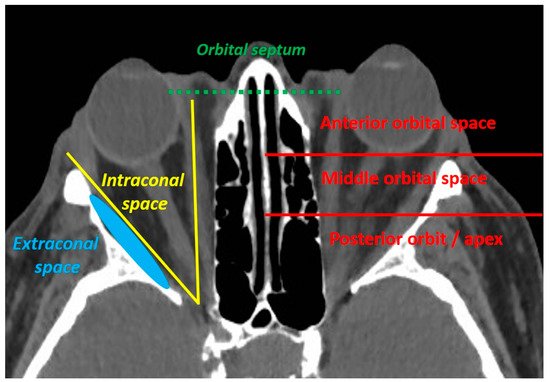

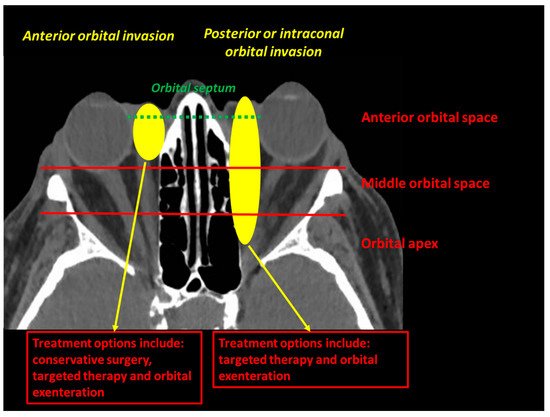

3]. An orbital involvement is defined as an orbital septum violation by the tumour. The orbital invasion should be classified as anterior, middle or posterior, and the extraconal or intraconal involvement should be specified ().

Figure 1. The orbital invasion (defined as an orbital septum violation) by an eyelid malignant tumour can be defined as intraconal (if located inside the oculomotor muscle cone) or extraconal (if located outside the oculomotor muscle cone), and should be located according to its depth (anterior, middle or posterior orbit).

Until recently, an eyelid malignancy invading the orbit was considered an indication for orbital exenteration (OE). However, OE is a radical, disfiguring and psychologically traumatic surgical procedure often refused by patients [

4]. In addition, OE cannot be offered to one-eyed patients. Therefore, several authors have tried to develop ‘eye-sparing’ strategies based on conservative surgical techniques followed or not by radiotherapy [

2]. Although being attractive, conservative combined eyelid and orbital surgeries have been associated with several post-operative complications, limiting their interest [

4]. In addition, several patients have experienced vision loss, and secondary eye amputation was sometimes required [

2,

3]. Therefore, a distinction between ‘eye-sparing’ and ‘sight-sparing’ strategies has emerged [

4]. Over the last decade, targeted therapies such as anti-SMO (smoothened protein) therapies for the treatment of BCC have emerged as a viable strategy for locally advanced periocular malignant tumours. These new targeted therapies and immunotherapies have opened a new era towards personalised periocular cancer treatment.

The aim of this review was to summarise the evolution of the management of periocular malignant tumours over the last three decades and highlight the current paradigm shift towards the use of ‘eye-sparing’ strategies.

2. Method for Literature Search

A thorough literature search was performed on Medline (

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) over the 2001–2021 period using the main search term ‘(orbital exenteration) or (periocular tumors)’ and the following terms: ‘eye sparing’, ‘globe sparing’, ‘targeted therapy’ and ‘immunotherapy’. Title and abstracts were reviewed by two independent authors. References were also obtained from citations in papers identified in the original search. Only relevant articles focused on eye-sparing strategies (e.g., conservative surgery, orbital radiotherapy, targeted therapy or immunotherapy) and written in English or French were considered. A few select articles published before 2001 were included in the text for historical and didactic purposes; however, the review was mainly based on articles published over the past 2 decades.

3. Orbital Exenteration for Locally Advanced Periocular Malignant Tumours

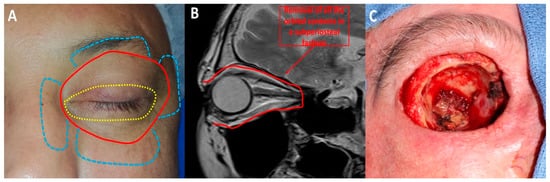

OE is a radical surgical procedure consisting of the removal of the entire orbital contents, including the eye and oculomotor muscles, in a subperiosteal fashion () [

5]. Historically, OE was first described in 1583 by Bartisch et al. [

6]. Depending on the tumour location and extent, OE may be enlarged to the adjacent sinus cavities or anterior cranial fossa. Reconstruction differs depending on the surgeon’s speciality and ranges from spontaneous granulation of the orbital socket to more complex and time-consuming free flaps [

7]. Cosmetic rehabilitation is better achieved with an orbital prosthesis retained by orbital implants, skin glue or glasses [

4]. Cosmetic rehabilitation depends on orbital socket healing and is often delayed, especially in the case of orbital implant placement [

5]. Although recent progress has been made in terms of reconstructive strategies and cosmetic rehabilitation [

4], OE is associated with anxiety and depression [

8]. Periocular eyelid malignant tumours invading the orbit are the most common indication for OE [

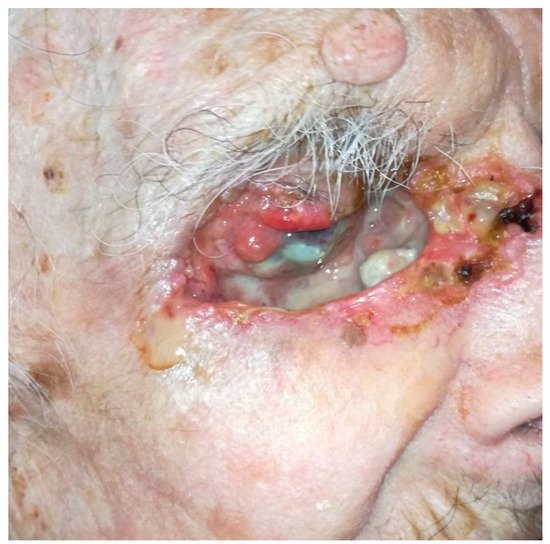

9]. BCC is one of the most common eyelid malignant tumours invading the orbit. Although BCC virtually does not metastasise, it is associated with local aggressiveness, as shown in . Other potential metastatic malignant tumours, such as SCC, melanoma or lacrimal gland tumours, often require OE. To date, no studies with a high level of evidence have shown the benefit of OE compared with conservative surgery in terms of overall survival [

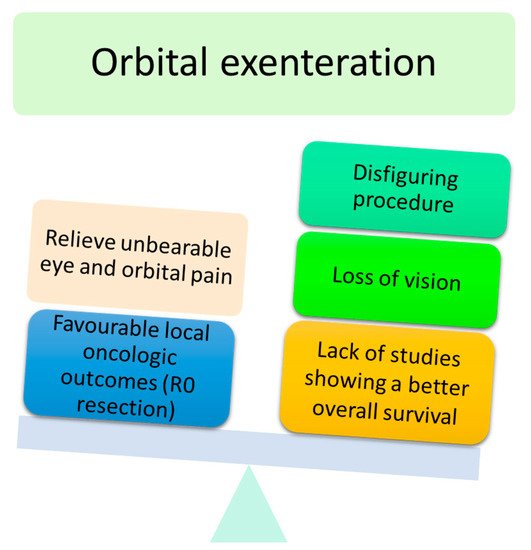

4]. The advantages and disadvantages of OE are shown in .

Figure 2. Orbital exenteration: (A) Several techniques have been described: eyelid-sparing orbital exenteration (yellow), total orbital exenteration (red) and orbital exenteration extended to surrounding orbital structures (blue). (B) Orbital exenteration consists of removing all the orbital contents. (C) Intraoperative photograph of a case of total orbital exenteration.

Figure 3. ‘Pseudo-orbital exenteration’ of an eyelid BCC with orbital invasion.

Figure 4. Main advantages and disadvantages of orbital exenteration.

Ophthalmologists have to deal with a very psychologically and anatomically traumatic surgery, which is sometimes refused by patients and cannot be performed in one-eyed patients. Therefore, several authors have tried to develop more conservative strategies called ‘eye-sparing’ strategies ().

4. First Step towards Eye-Sparing Strategies: Conservative Surgery Followed or Not by Adjuvant Radiotherapy

In 2005, Leibovitch et al. [

2] were the first to introduce the concept of ‘eye-sparing’ strategies by reporting their experience with 64 BCC patients with orbital invasion. Of these 64 patients, 16 were not treated with OE due to patient’s refusal, one-eyed patients or unresectable tumours (intraconal or posterior orbital location). These 16 patients were treated with conservative surgery alone, radiotherapy alone or a combination of both [

2]. Tumour recurrence was found in 2.8%, 16.7% and 25% of patients treated with OE, surgical excision alone and radiotherapy alone, respectively. They found that about 25% of patients treated with radiotherapy developed mild side effects such as dry eye syndrome or mild radiation retinopathy. They concluded that, in highly selected patients (e.g., one-eyed patients and patients with anterior and extraconal orbital involvement), an eye-sparing strategy could be an alternative to OE.

In 2010, Madge et al. [

3] have published the results of a multicentric international study assessing the outcomes of conservative eye-sparing surgery in 20 patients with locally advanced eyelid BCC. Only patients with anterior orbital invasion were included. All the tumours originated from the medial canthal area. Conservative surgery consisted of wide tumour and lacrimal sac resection guided by rapid paraffin or frozen section histological margin control followed by local and/or regional flaps. Complete surgical excision (R0 resection) was achieved in 90% of patients. Adjuvant orbital radiotherapy was performed in the two (10%) patients with positive surgical margins. After a mean clinical and radiological follow-up of 2 years, only one (5%) patient experienced tumour recurrence and, thus, underwent OE. Despite these favourable oncological outcomes, enthusiasm must be tempered. Indeed, 60% of patients experienced post-operative restrictive diplopia related to reduced medial rectus motility. Among them, three patients experienced diplopia in the primary gaze and one wore an eye patch to relieve double vision. Permanent epiphora was diagnosed in 75% of patients. About 60% of patients underwent a subsequent surgical revision for conjunctival, eyelid or lacrimal disorders. About 85% of patients had a stable visual acuity throughout the study. For the first time, this study reported excellent oncological outcomes and visual preservation after conservative surgery. However, the post-operative complications, high rate of surgical revisions and need for a close clinical and radiological follow-up should be taken into account, especially in elderly patients.

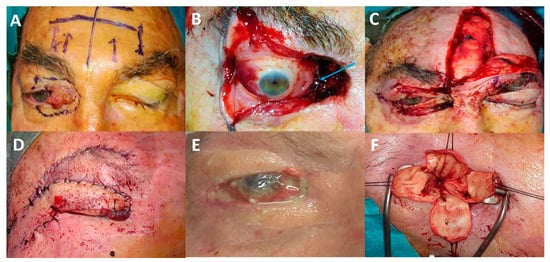

Data on eye-sparing surgery in more aggressive eyelid malignant tumours, such as SCCs or sebaceous carcinomas, are limited. In our experience with eyelid SCC invading the anterior orbit, achieving clear surgical margins is more challenging due to the invasive nature of the tumour (). Adjuvant radiotherapy is more likely to increase the rate of complications such as eyelid retraction, lagophthalmos, severe keratitis, dry eye, neovascular glaucoma and optic neuropathy [

4,

10]. Several authors have used eye-sparing strategies (conservative surgery plus adjuvant photon or particle radiotherapy) for the treatment of lacrimal gland or sinus carcinomas [

11,

12,

13]. Between 10% and 50% of patients experienced a visual decrease over time. In certain circumstances, patients may experience a complete visual loss and unbearable eye pain. Such patients often ask for eye amputation to improve their quality of life (). Finally, adjuvant orbital radiotherapy is known to impair orbital socket healing in the case of secondary OE.

Figure 5. Illustrative case of eye-sparing surgery: (A) A 68-year-old patient with upper and lower eyelid squamous cell carcinoma with anterior and extraconal orbital involvement. (B) Removal of half of the upper and lower eyelids, lacrimal sac and tantalum clip placement for adjuvant proton beam therapy (blue arrow). (C) Reconstruction performed using a tarsal graft, a conchal graft and a frontalis muscle flap. (D) Second surgery: frontotemporal flap (Fricke flap) used to correct the upper eyelid retraction and subsequent corneal exposure. (E) Flap retraction associated with chronic painful corneal ulcer. (F) Third surgery: eye evisceration to relieve unbearable eye pain.

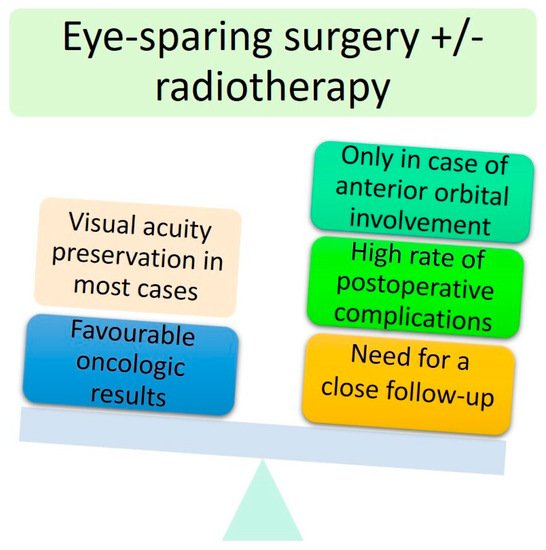

To conclude, eye-sparing strategies appear to be a viable procedure for locally advanced periocular malignant tumours with anterior and extraconal orbital involvement, especially in one-eyed patients. However, most patients will experience post-operative complications, and subsequent surgical revision will be needed with the risk of a significantly reduced quality of life. OE remains the mainstay of treatment for more posteriorly located tumours (intraconal middle and posterior tumours). For more aggressive malignant tumours (SCC and sebaceous carcinoma), the need for adjuvant orbital radiotherapy will probably worsen the visual impairment. Therefore, it is essential to distinguish ‘eye-sparing’ from ‘sight-sparing’ strategies [

4]. The advantages and disadvantages of ‘eye-sparing’ strategies are summarised in .

Figure 6. Main advantages and disadvantages of conservative surgery.

5. Second Step towards Eye-Sparing Strategies: Use of Targeted Therapies and Immunotherapies

5.1. Targeted Therapies in Locally Advanced BCC: More Questions Than Answers?

The first revolution occurred in 2012 when anti-SMO targeted therapies emerged as a viable treatment for locally advanced BCC [

14]. About 90% of BCCs carry a disactivating mutation in the

PTCH1 gene. This mutation results in an overactivation of the Hedgehog signalling pathway via the SMO receptor, leading to an anarchic cell proliferation that ultimately results in BCC. Vismodegib and sonidegib are two anti-SMO therapies approved by the FDA. Recently, anti-SMO therapies have been used for the treatment of ‘locally advanced’ periocular BCC. These studies are briefly summarised in . This table allows for a better understanding of the current limitations and lack of clear guidelines for anti-SMO therapies in periocular BCC.

Table 1. Main studies that assessed anti-SMO targeted therapies in locally advanced periocular BCC.

| Author, Year |

Number of Patients |

Number (%) of Patients with Orbital Involvement |

Mean (Range) Treatment Duration (Months) |

Number (%) of Patients Achieving a Complete Response |

Number (%) of Patients Achieving an Incomplete Response |

Number (%) of Patients with a Progressive Disease |

Number (%) of Patients Undergoing Adjuvant Surgical Excision |

Number (%) of Patients Undergoing Secondary Orbital Exenteration |

Number (%) of Patients Who Discontinued Treatment Due to Excessive Side Effects (%) |

Mean (Range) Follow-Up (Months) |

| Wong, 2015 [15] |

15 |

10 (67) |

13 (2–40) |

10 (67) |

3 (20) |

2 (13) |

1 (7) |

3 (20) |

5 (33) |

36 (14–52) |

| Sagiv, 2018 [16] |

8 |

6 (75) |

14 * (4–36) |

5 (62.5) † |

3 (37.5) |

0 (0) |

8 (100) |

0 (0) |

2 (25) |

18 (6–43) |

| Eiger-Moscovich, 2019 [17] |

21 |

15 (71.5) |

9 * (1–53) |

10 (48) |

11 (52) |

0 (0) |

1 (4.7) |

1 (4.7) |

8 (38) |

26 * (9–60) |

| Oliphant, 2020 [18] |

13 |

7 (58) |

7 (2–36) |

5 (38) |

8 (54) |

0 (0) |

6 (46) |

3 (23) |

1 (7.7) |

30 (12–48) |

| Ben Ishai, 2020 [19] |

244 ‡ |

NR |

10 * (5–19.5) |

70 (28.7) |

94 (38.5) |

5 (2) |

NR |

NR |

58 (23.8) |

10 * (5.7–14) |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13112822