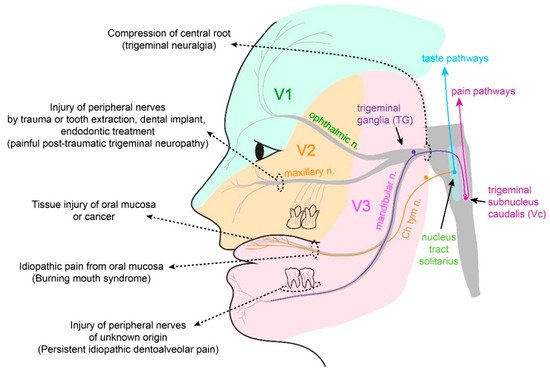

The oral cavity is a portal into the digestive system, which exhibits unique sensory properties. Like facial skin, the oral mucosa needs to be exquisitely sensitive and selective, in order to detect harmful toxins versus edible food. Chemosensation and somatosensation by multiple receptors, including transient receptor potential channels, are well-developed to meet these needs. In contrast to facial skin, however, the oral mucosa rarely exhibits itch responses. Like the gut, the oral cavity performs mechanical and chemical digestion. Therefore, the oral mucosa needs to be insensitive, to some degree, in order to endure noxious irritation. Persistent pain from the oral mucosa is often due to ulcers, involving both tissue injury and infection. Trigeminal nerve injury and trigeminal neuralgia produce intractable pain in the orofacial skin and the oral mucosa, through mechanisms distinct from those seen in the spinal area, which is particularly difficult to predict or treat. The diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic chronic pain, such as atypical odontalgia (idiopathic painful trigeminal neuropathy or post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathy) and burning mouth syndrome, remain especially challenging. The central integration of gustatory inputs might modulate chronic oral and facial pain. A lack of pain in chronic inflammation inside the oral cavity, such as chronic periodontitis, involves the specialized functioning of oral bacteria. A more detailed understanding of the unique neurobiology of pain from the orofacial skin and the oral mucosa should help us develop novel methods for better treating persistent orofacial pain.

- chronic pain

- mucosa pain

- orofacial pain

1. Introduction

| Table | Subtype |

|---|---|

| 1. Orofacial pain attributed to disorders of dentoalveolar and anatomically related structures | 1.1 Dental pain 1.2 Oral mucosal, salivary gland, and jawbone pains |

| 2. Myofascial orofacial pain | 2.1 Primary myofascial orofacial pain 2.2 Secondary myofascial orofacial pain |

| 3. Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) pain | 3.1 Primary temporomandibular joint pain 3.2 Secondary temporomandibular joint pain |

| 4. Orofacial pain attributed to lesion or disease of the cranial nerves | 4.1Pain attributed to lesion or diseaseofthetrigeminalnerve 4.2 Pain attributed to lesion or disease of the glossopharyngeal nerve |

| 5. Orofacial pains resembling presentations of primary headaches | 5.1 Orofacial migraine 5.2 Tension-type orofacial pain 5.3 Trigeminal autonomic orofacial pain 5.4 Neurovascular orofacial pain |

| 6. Idiopathic orofacial pain | 6.1 Burning mouth syndrome (BMS) 6.2 Persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP) 6.3 Persistent idiopathic dentoalveolar pain 6.4 Constant unilateral facial pain with additional attacks (CUFPA) |

2. Physiological Somatosensation and Pain from Oral Mucosa and Facial Skin

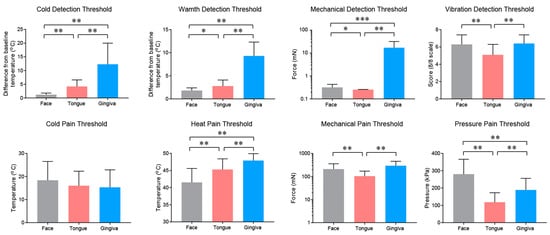

2.1. Somatosensation of Oral Mucosa and Facial Skin

2.2. Properties and Projections of Primary Afferents in Oral Mucosa and Facial Skin

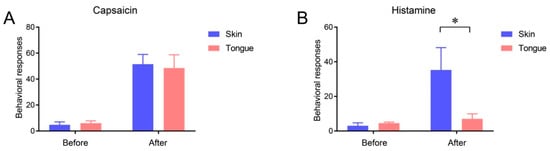

2.3. Itch Sensation of Oral Mucosa Is Weaker Than That of Facial Skin

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22115810

References

- Targhotra, M.; Chauhan, M.K. An Overview on Various Approaches and Recent Patents on Buccal Drug Delivery Systems. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2020, 26, 39.

- Glim, J.E.; Van Egmond, M.; Niessen, F.B.; Everts, V.; Beelen, R.H.J. Detrimental dermal wound healing: What can we learn from the oral mucosa? Wound Repair Regen. 2013, 21, 648–660.

- Bradley, R.M. Essentials of Oral Physiology; Mosby: St. Louis, MO, USA, 1995.

- Dubner, R. The Neural Basis of Oral and Facial Function; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1978.

- Zhao, N.N.; Whittle, T.; Murray, G.M.; Peck, C.C. The effects of capsaicin-induced intraoral mucosal pain on jaw movements in humans. J. Orofac. Pain 2012, 26, 277–287.

- Mirabile, A.; Airoldi, M.; Ripamonti, C.; Bolner, A.; Murphy, B.; Russi, E.; Numico, G.; Licitra, L.; Bossi, P. Pain management in head and neck cancer patients undergoing chemo-radiotherapy: Clinical practical recommendations. Crit. Rev. Oncol. 2016, 99, 100–106.

- Sessle, B.J. Acute and Chronic Craniofacial Pain: Brainstem Mechanisms of Nociceptive Transmission and Neuroplasticity, and Their Clinical Correlates. Crit. Rev. Oral Biol. Med. 2000, 11, 57–91.

- Campillo, E.R.D.R.; López-López, J.; Chimenos-Küstner, E. Response to topical clonazepam in patients with burning mouth syndrome: A clinical study. Bulletin GIRSO 2010, 49, 19–29.

- Pigg, M.; Baad-Hansen, L.; Svensson, P.; Drangsholt, M.; List, T. Reliability of intraoral quantitative sensory testing (QST). Pain 2010, 148, 220–226.

- Bearelly, S.; Cheung, S.W. Sensory Topography of Oral Structures. JAMA Otolaryngol. Neck Surg. 2017, 143, 73–80.

- Cordeiro, P.G.; Schwartz, M.; Neves, R.; Tuma, R. A Comparison of Donor and Recipient Site Sensation in Free Tissue Reconstruction of the Oral Cavity. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1997, 39, 461–468.

- McMillan, A.S. Pain-pressure threshold in human gingivae. J. Orofac. Pain 1995, 9, 44–50.

- Wang, Y.; Mo, X.; Zhang, J.; Fan, Y.; Wang, K.; Peter, S. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) in the orofacial region of healthy Chinese: Influence of site, gender and age. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2017, 76, 58–63.

- Poulsen, C.E.; Bendixen, K.H.; Terkelsen, A.J.; May, A.; Hansen, J.; Svensson, P. Region-Specific Effects of Trigeminal Capsaicin Stimulation. J. Oral Facial Pain Headache 2019, 33, 318–330.

- Naganawa, T.; Baad-Hansen, L.; Ando, T.; Svensson, P. Influence of topical application of capsaicin, menthol and local anesthetics on intraoral somatosensory sensitivity in healthy subjects: Temporal and spatial aspects. Exp. Brain Res. 2015, 233, 1189–1199.

- Albin, K.C.; Carstens, M.I.; Carstens, E. Modulation of Oral Heat and Cold Pain by Irritant Chemicals. Chem. Sens. 2008, 33, 3–15.

- Kalantzis, A.; Robinson, P.; Loescher, A. Effects of capsaicin and menthol on oral thermal sensory thresholds. Arch. Oral Biol. 2007, 52, 149–153.

- Trulsson, M.; Essick, G.K. Sensations Evoked by Microstimulation of Single Mechanoreceptive Afferents Innervating the Human Face and Mouth. J. Neurophysiol. 2010, 103, 1741–1747.

- Jacobs, R.; Wu, C.-H.; Goossens, K.; Van Loven, K.; Van Hees, J.; Van Steenberghe, D. Oral mucosal versus cutaneous sensory testing: A review of the literature. J. Oral Rehabil. 2002, 29, 923–950.

- Moayedi, Y.; Duenas-Bianchi, L.F.; Lumpkin, E.A. Somatosensory innervation of the oral mucosa of adult and aging mice. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9975.

- Toda, K.; Ishii, N.; Nakamura, Y. Characteristics of mucosal nociceptors in the rat oral cavity: An in vitro study. Neurosci. Lett. 1997, 228, 95–98.

- Grayson, M.; Furr, A.; Ruparel, S. Depiction of Oral Tumor-Induced Trigeminal Afferent Responses Using Single-Fiber Electrophysiology. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4574.

- Urata, K.; Shinoda, M.; Honda, K.; Lee, J.; Maruno, M.; Ito, R.; Gionhaku, N.; Iwata, K. Involvement of TRPV1 and TRPA1 in Incisional Intraoral and Extraoral Pain. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 446–454.

- Kichko, T.I.; Neuhuber, W.; Kobal, G.; Reeh, P.W. The roles of TRPV1, TRPA1 and TRPM8 channels in chemical and thermal sensitivity of the mouse oral mucosa. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2018, 47, 201–210.

- Kovačič, U.; Tesovnik, B.; Molnar, N.; Cör, A.; Skalerič, U.; Gašperšič, R. Dental pulp and gingivomucosa in rats are innervated by two morphologically and neurochemically different populations of nociceptors. Arch. Oral Biol. 2013, 58, 788–795.

- Wang, S.; Kim, M.; Ali, Z.; Ong, K.; Pae, E.K.; Chung, M.K. TRPV1 and TRPV1-Expressing Nociceptors Mediate Orofacial Pain Behaviors in a Mouse Model of Orthodontic Tooth Movement. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 1207.

- Gašperšič, R.; Kovačič, U.; Cör, A.; Skaleric, U. Unilateral ligature-induced periodontitis influences the expression of neuropeptides in the ipsilateral and contralateral trigeminal ganglion in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2008, 53, 659–665.

- Yajima, T.; Sato, T.; Hosokawa, H.; Kondo, T.; Saito, M.; Shimauchi, H.; Ichikawa, H. Distribution of transient receptor potential melastatin-8-containing nerve fibers in rat oral and craniofacial structures. Ann. Anat. Anat. Anz. 2015, 201, 1–5.

- Wang, T.; Jing, X.; DeBerry, J.J.; Schwartz, E.S.; Molliver, D.C.; Albers, K.M.; Davis, B.M. Neurturin Overexpression in Skin Enhances Expression of TRPM8 in Cutaneous Sensory Neurons and Leads to Behavioral Sensitivity to Cool and Menthol. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 2060–2070.

- Wu, P.; Arris, D.; Grayson, M.; Hung, C.-N.; Ruparel, S. Characterization of sensory neuronal subtypes innervating mouse tongue. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0207069.

- Chichorro, J.G.; Porreca, F.; Sessle, B. Mechanisms of craniofacial pain. Cephalalgia 2017, 37, 613–626.

- Carstens, E.; Kuenzler, N.; Handwerker, H.O. Activation of neurons in rat trigeminal subnucleus caudalis by different irritant chemicals applied to oral or ocular mucosa. J. Neurophysiol. 1998, 80, 465–492.

- Noma, N.; Tsuboi, Y.; Kondo, M.; Matsumoto, M.; Sessle, B.J.; Kitagawa, J.; Saito, K.; Iwata, K. Organization of pERK-immunoreactive cells in trigeminal spinal nucleus caudalis and upper cervical cord following capsaicin injection into oral and craniofacial regions in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2008, 507, 1428–1440.

- Bay, B.; Hilliges, M.; Weidner, C.; Sandborgh-Englund, G. Response of human oral mucosa and skin to histamine provocation: Laser Doppler perfusion imaging discloses differences in the nociceptive nervous system. Acta Odontol. Scand. 2009, 67, 99–105.

- Imamachi, N.; Park, G.H.; Lee, H.; Anderson, D.J.; Simon, M.I.; Basbaum, A.I.; Han, S.-K. TRPV1-expressing primary afferents generate behavioral responses to pruritogens via multiple mechanisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 11330–11335.

- Barry, D.M.; Liu, X.-T.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.-Y.; Gao, F.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Wilhelm, S.; Yin, J.; et al. Exploration of sensory and spinal neurons expressing gastrin-releasing peptide in itch and pain related behaviors. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–14.