Episcleritis and scleritis are the most common ocular inflammatory manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis.

- scleritis

- episcleritis

- rheumatoid arthritis

- ocular inflammation

1. Introduction

2. Demographics, Presentation, and Classification of Episcleritis and Scleritis

3. Episcleritis/Scleritis and Rheumatoid Arthritis

4. Treatment modalities and perspectives

4.1. Episcleritis

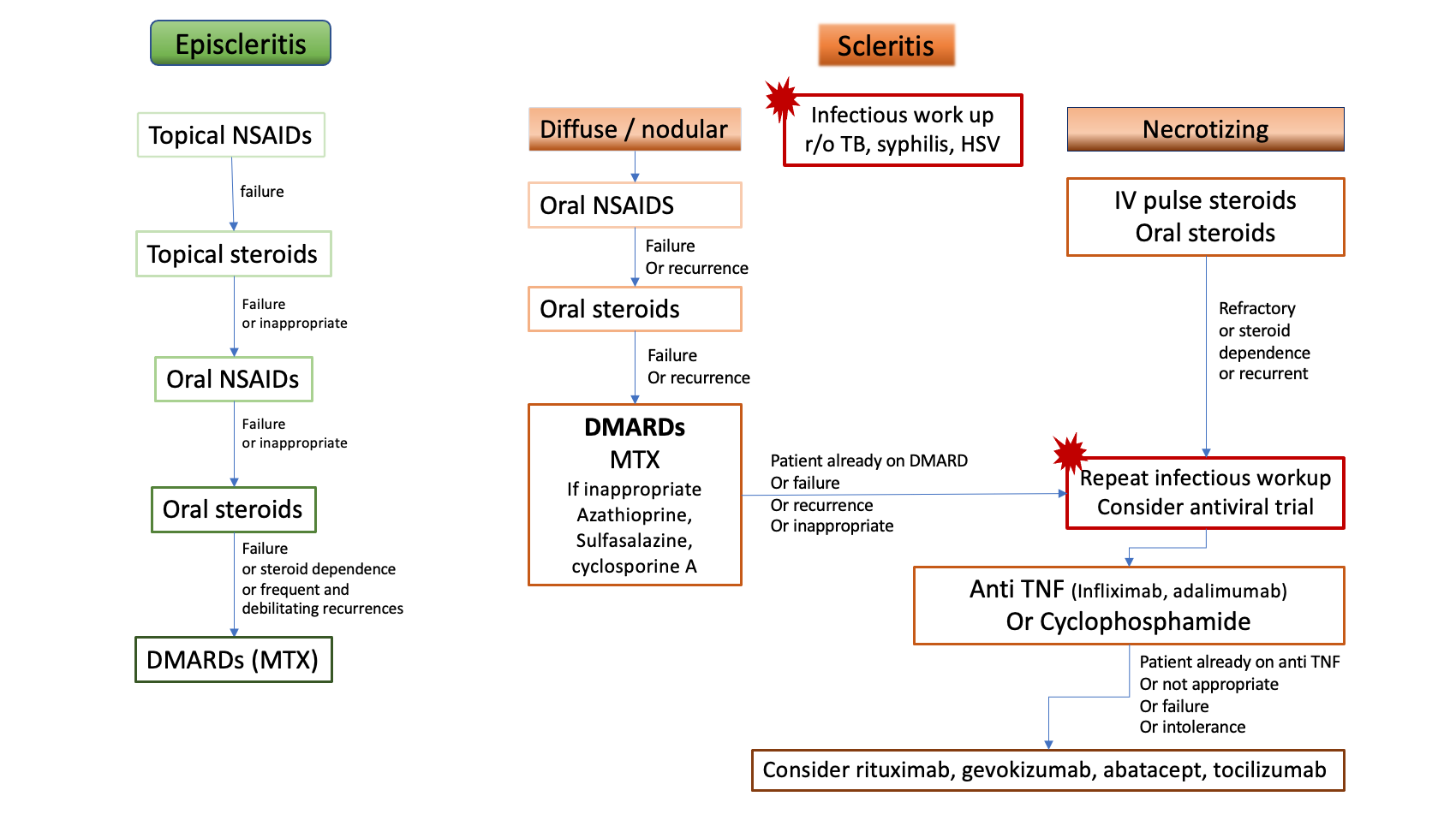

The management of episcleritis is most often fairly benign, involving oral non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or topical steroids, topical NSAIDs and artificial tears [3][6]. In refractory or recurrent cases, periocular steroid injections, oral steroids, or, very rarely, DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine, leflunomide, methotrexate, may be required [3].

4.2. Scleritis

Treatment strategies for scleritis classically include NSAIDs as a first line. Steroids, oral and/or intravenous pulse, may be required in more than 70% of patients [3]. Associated topical treatment can involve steroids, NSAIDs, cycloplegics, artificial tears, and/or cyclosporine [3].

DMARDs are reported to be used in half of the patients [3][10]: methotrexate [3][7][10][11], salazosulfapyridine [10], cyclophosphamide [3][7][11], cyclosporine A [7], or azathioprine [7]. To note, in a series of posterior scleritis, patients treated with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) showed a significantly accelerated time of relapse compared to other patients [8].

4.2.1 Biologic response modifiers

Treatment with biologics has been reported effective in small case series and case reports, with successful treatment of refractory cases with infliximab [16][17][18][19][20], adalimumab [21] or certolizumab pegol [22], then in larger series where up to 30% of scleritis patients required biologic response modifiers to achieve control of the inflammation [3][7][10][11]. Based on all the available evidence, recommendations from the American Academy of Ophthalmology were issued in 2014: anti-TNF therapy with infliximab or adalimumab should be considered for patients with scleritis who have failed first-line immunomodulatory therapies [23]. Thus, treatment with infliximab or adalimumab or cyclophosphamide should be proposed to patients who either were already on DMARD at the onset of scleritis or have failed a conventional DMARD, i.e inability to control the inflammation, inability to decrease the steroids to an acceptable level, or multiple recurrences. Anti TNF alpha should also be considered as a first line agent in necrotizing scleritis with direct threat to vision (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Proposition of treatment algorithm and strategy of escalation in rheumatoid arthritis-associated episcleritis and scleritis. DMARDs: disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs, HSV: Herpes Simplex Virus, IV: intravenous, MTX: methotrexate, NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, r/o: rule out, TB: tuberculosis, TNF: Tumor necrosis factor

Rituximab is a monoclonal antibody that recognizes CD-20, an antibody expressed on the surface of mature B lymphocytes, approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe RA [24]. It has been shown to be another promising agent in the treatment of refractory RA-associated scleritis, reported since 2009 [25]. Adverse effects may include reactivation of viruses, as reported with acute retinal necrosis [26]. The rationale for the use of rituximab in necrotizing scleritis associated with RA is supported by immunohistochemical evidence, from analysis of enucleated eyes with necrotizing scleritis, suggesting that inflammation, in the group of eyes with association to a systemic autoimmune disease, may be driven by B cells, while macrophages could play a role in the necrotizing process [27]. A phase I/II dose ranging randomized trial [28] evaluated treatment with 2 infusions of either 500 mg or 1000 mg at day 1 and day 15, along with intravenous methylprednisolone 100mg, and follow-up every 4 weeks for 24 weeks. In both dosing groups, rituximab was found effective, as in 9 out of 12 patients the inflammation was successfully controlled within 24 weeks of therapy. Peri-infusional disease exacerbations were noted in the 2- to 8 weeks period after infusion, requiring management with short term oral corticosteroid and careful tapering.

4.2.2. Subconjunctival injections

Options for local treatments are limited, but subconjunctival injections of triamcinolone or sirolimus could be a valuable option for patients with poor compliance with eyedrops, but also patients with severe comorbidities not eligible to systemic treatment. However, local treatment should not be considered for patients with necrotizing scleritis. Beside the risk of globe perforation, the onset of necrotizing scleritis is a strong indicator that the disease has transformed into a systemic microvasculitic disease, which needs to be addressed with vigorous systemic immunomodulation [29][30].

5. Necrotizing scleritis and rheumatoid vasculitis

The onset of necrotizing scleritis may precede or be concurrent with systemic rheumatoid vasculitis. In a patient with RA, even when the disease seems quiescent or stable, the occurrence of necrotizing scleritis or, similarly, PUK, is an evidence of slowly emerging, potentially lethal, visceral vasculitis [30]. In 1976, 27% of patients with necrotizing scleritis were dead within 8 years [6]. Jones et al [31] reported a mortality rate of over 36% in 3 years after a RA-associated scleritis and a 60% incidence of cardio-vascular events. Other reports from the pre-biologics era showed that up to 40% of patients with systemic rheumatoid vasculitis died within 5 years from systemic injuries of vasculitis, cardio-vascular events, or complications of treatments [32][33][34][35][36]. Even before biologics were available, in 1984 Foster et al [29] showed that patients treated aggressively with cyclophosphamide or methotrexate had a favorable life and ocular prognosis compared to patients managed with oral NSAIDs and steroids. The overall incidence of rheumatoid vasculitis has decreased over the past decade, from earlier and more aggressive management of RA as well as from decreased rates of smoking [37][38]. There is no consensus yet as to what sequence of treatment is optimal for ocular manifestations of rheumatoid vasculitis such as necrotizing scleritis or PUK. After infectious causes have been carefully ruled out, including if any doubt a trial antiviral treatment, it seems reasonable to offer intravenous pulse of methylprednisolone, or at least oral steroids, followed by initiation or escalation of immunosuppressants with a low threshold for establishment of a biologic treatment. Agents of choice would be anti TNF alpha for their rapidity of action and safety profile, or rituximab [37][38]. With adequate management of the systemic disease, it seems that the onset of scleritis in a RA patient is not necessarily a life-threatening event anymore. In the recent study of Caimmi et al, even though 39% of episcleritis and 29% of scleritis patients had developed a new extra articular manifestation of RA within 5 years, the survival rate at 10 years was comparable between patients with inflammatory ocular disease and a comparation group of RA patients without ocular disease. Similarly, there was no difference in the incidence of cardio-vascular events between groups of RA patients with or without inflammatory ocular disease [3].

6. Complications and incidence of resolution

Complications can be seen in 57% of scleritis [3][6] and include decrease in visual acuity, keratitis, cataract, ocular hypertension and glaucoma [10] and scleral thinning and defects. Fortunately, most patients retain a good vision [3][10], unless they develop persistent structural damage to the eye, cystoid macular oedema, peripheral corneal melt, interstitial keratitis, or scleritis-induced astigmatism [7]. In the 1976 series of Watson and Hayreh, 4 patients received corneo-scleral grafts, 2 patients a scleral graft, 3 patients underwent enucleation of the affected eye [6].

The incidence of resolution of ocular disease at 1 year is only 40% in scleritis, as compared to 60% in episcleritis [3]. Patients with scleritis associated with a systemic disease were more likely to have inflammation ongoing for more than 5 years in the study of Bernauer et al [7], and the presence of circulating antibodies (RF, ANA, ANCA) tended to increase the risk of persistent inflammation. Remission, defined as no active inflammation for at least 3 months after discontinuing all immunosuppressive medication [39], was obtained in only 8% of patients with RA-associated scleritis, compared to 30% of patients without RA. When remission was obtained, 86% remained in remission after 1 year of follow-up [39].

7. Conclusion

Severe, refractory cases of scleritis are a rare manifestation of extra-articular RA. Early recognition and appropriate treatment are crucial and again, good cooperation with the rheumatology or internal medicine specialist will be key. Although no consensus or guidelines exist, many options issued from the rheumatology practice will become available for the treatment of refractory scleritis (Table), once infectious causes are ruled out, allowing a rapid control of the inflammation and avoiding both structural damage to the eye and complications of long-term steroid use. Larger series and trials are needed to determine the best escalation strategy. But already the life-threatening prospect of rheumatoid vasculitis, following the onsetof scleritis, seems to have changed thanks to a more effective and safer control of the systemic inflammation.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm10102118

References

- Vignesh Paul Pandian; Renuka Srinivasan; Ocular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis and their correlation with anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibodies. Clinical Ophthalmology 2015, 9, 393-397, 10.2147/OPTH.S77210.

- Sujit Itty; Jose S. Pulido; Sophie J. Bakri; Keith H. Baratz; Eric L. Matteson; David O. Hodge; Anti-Cyclic Citrullinated Peptide, Rheumatoid Factor, and Ocular Symptoms Typical of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 2007, 106, 75-81, .

- Cristian Caimmi; Cynthia S. Crowson; Wendy M. Smith; Eric L. Matteson; Ashima Makol; Clinical Correlates, Outcomes, and Predictors of Inflammatory Ocular Disease Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis in the Biologic Era. The Journal of Rheumatology 2018, 45, 595-603, 10.3899/jrheum.170437.

- Raphael Guimarães Bettero; Ricardo Faraco Martinez Cebrian; Thelma Larocca Skare; Prevalência de manifestações oculares em 198 pacientes com artrite reumatóide: um estudo retrospectivo. Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia 2008, 71, 365-369, 10.1590/s0004-27492008000300011.

- Gordana Zlatanović; Dragan Veselinović; Sonja Cekic; Maja Zivković; Jasmina Đorđević- Jocić; Marko Zlatanović; Ocular manifestation of rheumatoid arthritis-different forms and frequency. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences 2010, 10, 323-327, 10.17305/bjbms.2010.2680.

- P. G. Watson; S. S. Hayreh; Scleritis and episcleritis.. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1976, 60, 163-191, 10.1136/bjo.60.3.163.

- Wolfgang Bernauer; Beat Pleisch; Matthias Brunner; Five-year outcome in immune-mediated scleritis. Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2014, 252, 1477-1481, 10.1007/s00417-014-2696-1.

- Alenka Lavric; Julio J. Gonzalez-Lopez; Parthopratim Dutta Majumder; Nishat Bansal; Jyotirmay Biswas; Carlos Pavesio; Rupesh Agrawal; Posterior Scleritis: Analysis of Epidemiology, Clinical Factors, and Risk of Recurrence in a Cohort of 114 Patients. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2015, 24, 6-15, 10.3109/09273948.2015.1005240.

- Phoebe Lin; Shaminder S. Bhullar; Howard H. Tessler; Debra A. Goldstein; Immunologic Markers as Potential Predictors of Systemic Autoimmune Disease in Patients with Idiopathic Scleritis. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2008, 145, 463-471.e1, 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.09.024.

- Atsushi Yoshida; Meri Watanabe; Akira Okubo; Hidetoshi Kawashima; Clinical characteristics of scleritis patients with emphasized comparison of associated systemic diseases (anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and rheumatoid arthritis). Japanese Journal of Ophthalmology 2019, 63, 417-424, 10.1007/s10384-019-00674-7.

- Eiman Abd El Latif; Mouamen M. Seleet; Hazem El Hennawi; Mohamed Abdulbadiea Rashed; HossamEldeen Elbarbary; Karim Sabry; Mohamed Abdelmonagy Ibrahim; Pattern of Scleritis in an Egyptian Cohort. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2018, 27, 890-896, 10.1080/09273948.2018.1544372.

- Peizeng Yang; Zi Ye; Jihong Tang; Liping Du; Qingyun Zhou; Jian Qi; Liang Liang; Lili Wu; Chaokui Wang; Mei Xu; et al. Clinical Features and Complications of Scleritis in Chinese Patients. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2016, 26, 387-396, 10.1080/09273948.2016.1241282.

- M. G. Cohen; E. K. Li; P. Y. Ng; K. L. Chan; EXTRA-ARTICULAR MANIFESTATIONS ARE UNCOMMON IN SOUTHERN CHINESE WITH RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS. Rheumatology 1993, 32, 209-211, 10.1093/rheumatology/32.3.209.

- So Jung Ryu; Min Ho Kang; Mincheol Seong; Heeyoon Cho; Yong Un Shin; Anterior scleritis following intravitreal injections in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Medicine 2017, 96, e8925, 10.1097/md.0000000000008925.

- Jyotirmay Biswas; A.C. Aparna; Annamalai Radha; K. Vaijayanthi; R. Bagyalakshmi; Tuberculous Scleritis in a Patient with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2011, 20, 49-52, 10.3109/09273948.2011.628195.

- R. Herrera-Esparza; E. Avalos-Diaz; Infliximab treatment in a case of rheumatoid scleromalacia perforans.. Reumatismo 2011, 61, 212-215, 10.4081/reumatismo.2009.212.

- Gracia M. Abalos Medina; José Gónzalez Domínguez; Gonzalo Ruiz Villaverde; Enrique Raya Álvarez; Infliximab para el tratamiento de la escleritis anterior necrosante asociada a artritis reumatoide seropositiva. Medicina Clínica 2010, 134, 235-236, 10.1016/j.medcli.2009.02.009.

- Ismael I. Atchia; C Elizabeth Kidd; R W. D. Bell; Rheumatoid Arthritis-Associated Necrotizing Scleritis and Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis Treated Successfully With Infliximab. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2006, 12, 291-293, 10.1097/01.rhu.0000249766.24780.95.

- D. Ashok; W. H. Ayliffe; P. D. W. Kiely; Necrotizing scleritis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: long-term remission with high-dose infliximab therapy. Rheumatology 2005, 44, 950-951, 10.1093/rheumatology/keh635.

- D Díaz-Valle; R Miguélez Sánchez; Mc Fernández Espartero; D Pascual Allen; Tratamiento de la escleritis anterior difusa refractaria con infliximab. Archivos de la Sociedad Española de Oftalmología 2004, 79, 405-408, 10.4321/s0365-66912004000800010.

- Lola E. Lawuyi; Avinash Gurbaxani; Refractory necrotizing scleritis successfully treated with adalimumab.. Journal of Ophthalmic Inflammation and Infection 2016, 6, 37, 10.1186/s12348-016-0107-y.

- Paul S Tlucek; Donald U Stone; Certolizumab Pegol Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis–Associated Scleritis. Cornea 2011, 31, 90-91, 10.1097/ico.0b013e318211400a.

- Grace Levy-Clarke; Douglas A. Jabs; Russell W. Read; James T. Rosenbaum; Albert Vitale; Russell N. Van Gelder; Expert Panel Recommendations for the Use of Anti–Tumor Necrosis Factor Biologic Agents in Patients with Ocular Inflammatory Disorders. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 785-796.e3, 10.1016/j.ophtha.2013.09.048.

- Stanley B. Cohen; Paul Emery; Maria W. Greenwald; Maxime Dougados; Richard A. Furie; Mark C. Genovese; Edward C. Keystone; James E. Loveless; Gerd-Rüdiger Burmester; Matthew W. Cravets; et al. Rituximab for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to anti–tumor necrosis factor therapy: Results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial evaluating primary efficacy and safety at twenty-four weeks. Arthritis Care & Research 2006, 54, 2793-2806, 10.1002/art.22025.

- S Chauhan; A Kamal; R N Thompson; C Estrach; R J Moots; Rituximab for treatment of scleritis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2009, 93, 984-985, 10.1136/bjo.2008.147157.

- Sarah Schuler; Matthias Brunner; Wolfgang Bernauer; Rituximab and Acute Retinal Necrosis in a Patient with Scleromalacia and Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ocular Immunology and Inflammation 2015, 24, 96-98, 10.3109/09273948.2014.999377.

- Yoshihiko Usui; Jignesh Parikh; Hiroshi Goto; Narsing A Rao; Immunopathology of necrotising scleritis. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2008, 92, 417-419, 10.1136/bjo.2007.126425.

- Eric B. Suhler; Lyndell L. Lim; Robert M. Beardsley; Tracy R. Giles; Sirichai Pasadhika; Shelly T. Lee; Alexandre De Saint Sardos; Nicholas J. Butler; Justine R. Smith; James T. Rosenbaum; et al. Rituximab Therapy for Refractory Scleritis. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1885-1891, 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.044.

- C. Stephen Foster; S. Lance Forstot; Louis A. Wilson; Mortality Rate in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Developing Necrotizing Scleritis or Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis. Ophthalmology 1984, 91, 1253-1263, 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34160-4.

- C. Stephen Foster; Ocular manifestations of the potentially lethal rheumatologic and vasculitic disorders. Journal Français d'Ophtalmologie 2013, 36, 526-532, 10.1016/j.jfo.2012.12.004.

- Jones, P.; Jayson, M.I; Rheumatoid Scleritis: A Long-Term Follow Up. Proc R Soc Med 1973, 66, 1161–1163, .

- D. D. McGavin; J. Williamson; J. V. Forrester; W. S. Foulds; W. W. Buchanan; W. C. Dick; P. Lee; R. N. Macsween; K. Whaley; Episcleritis and scleritis. A study of their clinical manifestations and association with rheumatoid arthritis.. British Journal of Ophthalmology 1976, 60, 192-226, 10.1136/bjo.60.3.192.

- C C Erhardt; P A Mumford; P J Venables; R N Maini; Factors predicting a poor life prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: an eight year prospective study.. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1988, 48, 7-13, 10.1136/ard.48.1.7.

- A E Voskuyl; A H Zwinderman; M L Westedt; J P Vandenbroucke; F C Breedveld; J M Hazes; Factors associated with the development of vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis: results of a case-control study.. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 1996, 55, 190-192, 10.1136/ard.55.3.190.

- Turesson, C.; O’Fallon, W.M.; Crowson, C.S.; Gabriel, S.E.; Matteson, E.L; Occurrence of Extraarticular Disease Manifestations Is Associated with Excess Mortality in a Community Based Cohort of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002, 29, 62-67, .

- Xavier Puéchal; Gérard Said; Pascal Hilliquin; Joël Coste; Chantal Job-Deslandre; Catherine Lacroix; Charles J. Menkès; Peripheral neuropathy with necrotizing vasculitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care & Research 1995, 38, 1618-1629, 10.1002/art.1780381114.

- Ashima Makol; Eric L. Matteson; Kenneth J. Warrington; Rheumatoid vasculitis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2014, 27, 63-70, 10.1097/bor.0000000000000126.

- Shweta Kishore; Lisa Maher; Vikas Majithia; Rheumatoid Vasculitis: A Diminishing Yet Devastating Menace. Current Rheumatology Reports 2017, 19, 39, 10.1007/s11926-017-0667-3.

- John Harold Kempen; Maxwell Pistilli; Hosne Begum; Tonetta D. Fitzgerald; Teresa L. Liesegang; Abhishek Payal; Nazlee Zebardast; Nirali P. Bhatt; C. Stephen Foster; Douglas A. Jabs; et al. Remission of Non-Infectious Anterior Scleritis: Incidence and Predictive Factors. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2021, 223, 377-395, 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.024.

- John Harold Kempen; Maxwell Pistilli; Hosne Begum; Tonetta D. Fitzgerald; Teresa L. Liesegang; Abhishek Payal; Nazlee Zebardast; Nirali P. Bhatt; C. Stephen Foster; Douglas A. Jabs; et al. Remission of Non-Infectious Anterior Scleritis: Incidence and Predictive Factors. American Journal of Ophthalmology 2021, 223, 377-395, 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.03.024.