Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

Adverse food reactions include immune-mediated food allergies and non-immune-mediated intolerances. However, this distinction and the involvement of different pathogenetic mechanisms are often confused. Furthermore, there is a discrepancy between the perceived vs. actual prevalence of immune-mediated food allergies and non-immune reactions to food that are extremely common. The risk of an inappropriate approach to their correct identification can lead to inappropriate diets with severe nutritional deficiencies.

- food allergy

- food intolerance

- nutrition

- nutritional concerns

1. Introduction

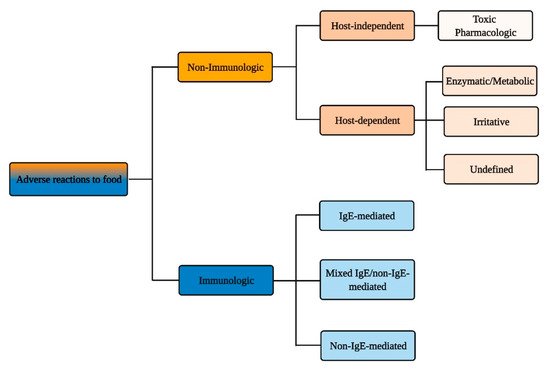

According to the authoritative definition issued in 2010 by an Expert Panel Report sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), food allergy is defined as “an adverse health effect arising from a specific immune response that occurs reproducibly on exposure to a given food” and food intolerance as “nonimmune reactions that include metabolic, toxic, pharmacologic, and undefined mechanisms” [1]. Yet, this distinction and the diversity of events and pathologies that lies behind it (Figure 1) is not clearly embodied in the public perception of the adverse reactions that can occur following food intake.

Figure 1. Immunologic vs. non-immunologic adverse reactions to food.

It is well established that the prevalence of true IgE-mediated food allergy is significantly less common than food allergy identified as self-reported disease, yet even epidemiological data reflect the difficulty in the identification of bona fide IgE-mediated allergy, as several reports do not include a clinical confirmation of disease [2].

Stringent surveys of food allergy prevalence indicate, at least in westernized countries, a trend towards greater persistence of pediatric food allergies and higher rates of adult-onset cases than previously appreciated [2][3]. The impact of therapeutic food allergy regimens on nutritional needs will therefore need to be adjusted according to this expanding spectrum [4], as this is the cornerstone of all types of food allergy prevention, from primary to tertiary [5]. This evolving landscape for immediate hypersensitivity reactions to food, as well as increased knowledge on non-IgE- or mixed IgE/non-IgE immunological responses brings increasing nutritional challenges for diseases in which long-term food elimination is a primary therapeutic strategy [6], underscoring the key role of a correct dietary approach strictly driven by appropriate diagnostics [7].

2. Immunologic Adverse Reactions to Food

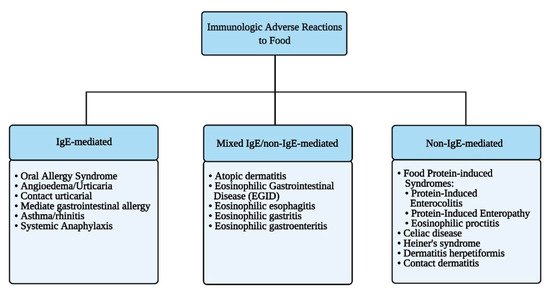

Immune-mediated reactions to food can be classified depending on the involvement of IgE-mediated and/or other immune responses to ingested antigens (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Immunologic adverse reactions to food.

2.1. IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

IgE-mediated food allergy is generally characterized by its rapid onset, which can be within minutes to an hour after ingesting the allergen, according to the World Allergy Organization (WAO). The signs and symptoms can be mild and localized to mucocutaneous manifestations or can involve different systems that are concomitantly affected in systemic anaphylaxis (Table 1).

Table 1. Clinical presentations of IgE-mediated food allergy beyond the GI system.

The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is a common target for immediate hypersensitivity reactions to food [1][8][9] with the main clinical presentations being the oral allergic syndrome (OAS) and the symptoms of immediate GI hypersensitivity. OAS, also known as pollen-food syndrome, is characterized by itching and tingling sensation of the oral mucosa and/or upper pharynx, the erythema of the perioral and oral mucosa with mild edema that occurs within minutes from ingestion of some foods, especially fresh fruits, and vegetables [10]. This localized reaction occurs primarily in patients with respiratory allergies (rhinoconjunctivitis, asthma) that have specific IgE directed against panallergens, which are proteins featuring homologous epitopes present in seasonal or perennial aeroallergens (such as pollens) and certain foods—mostly fruits and vegetables [11][12]. Patients with birch-pollen hay fever may have OAS symptoms after ingesting hazelnut, apple, carrot, and celery, whereas patients with IgE-mediated sensitivity to ragweed pollen may react to melons (e.g., watermelon or cantaloupe) and banana. The signs and symptoms rarely involve areas beyond those directly involved in the first contact with the culprit food and are mostly self-limiting. This occurs as the epitopes involved are conformational and thus are recognized by specific IgE only in the native form of the protein and no longer once denatured by gastric low pH. Accordingly, most patients with OAS can tolerate the triggering food when it is consumed cooked, as epitopes are destroyed by the heating process. These are important features differentiating OAS from an initial presentation of a more generalized allergic reaction, such as an urticaria/angioedema developing either as an isolated cutaneous reaction or as part of an anaphylactic response.

The symptoms of immediate GI hypersensitivity include nausea, abdominal pain, cramps, vomiting, and/or watery/mucous diarrhea. Acute vomiting is the most common presentation and the one best documented as immunological and IgE-mediated. Other IgE-mediated food-induced allergic manifestations are listed in Table 1.

Anaphylaxis is a serious allergic reaction that is rapid in onset and may be life-threatening [13]. It can be mediated by IgE, or by other immunological or non-immunological mechanisms [14]. According to the current NIAID criteria, anaphylaxis is highly likely when there is the acute onset of an illness (minutes to several hours) with either (1) cutaneous manifestations associated with the involvement of respiratory or cardiovascular system (dizziness, weakness, tachycardia, hypotension, syncope); (2) an association of at least two or more among cutaneous, respiratory, GI, and cardiovascular manifestations associated with exposure to a likely allergen for that patient; or (3) isolated reduced blood pressure after exposure to known allergen for that patient [14]. Food is one of the most common causes of anaphylaxis, with most surveys indicating that food-induced reactions account for 30–50% of anaphylaxis cases in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia, and for up to 81% of anaphylaxis cases in children [15]. Peanut, tree nuts (walnut, almond, pecan, cashew, hazel nut, Brazil nut, etc.), milk, egg, sesame seeds, fish and shellfish, wheat, and soy are the most common food triggers worldwide; however, any food can potentially trigger anaphylaxis. It is important to underscore that in some severely allergic patients, even a very small amount of food can cause a life-threatening reaction: some individuals can develop symptoms upon exposure to fumes from triggering foods being cooked (e.g., fish) or coming in contact with biological fluids (saliva, seminal fluid) of people who has eaten the food they are allergic to [16][17].

Prevalence of food allergy varies widely in different geographical locations, depending upon the influence of cultures on dietary habits. For example, peanut allergy is one of the most common causes of food anaphylaxis in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia, but it is rare in Italy and Spain, where consumption of peanut is significantly lower; conversely, consumption of peach and peach allergy are very frequent in Southern Europe and very rare in Northern Europe [3][18]. Along this line, anaphylactic reactions have been reported after the ingestion of insects such as beetles (mealworm, superworm, silkworm) or carmine red (E120), a color additive used in the food industry, obtained from cochineal scale insects such as Dactylopius coccus [19][20][21][22]. Although insects, as well as other foods (e.g., jellyfish), are consumed mainly in selected geographical areas in Eastern Asia, Africa, and Latin America, allergic reactions to these foods might become more common worldwide concomitant with the globalization of dietary habits. In any instance, robust observational findings, coming from consolidated diagnostic procedures, such as properly controlled in vivo challenges (see below), are very difficult to obtain on a large scale. Therefore, inconsistent definitions and methodologies are used in different studies, most of which are based on self-reporting, which generally overestimates food allergy prevalence [3]. A systematic review that included 42 studies conducted in Europe between 2000 and 2012 found a very poor correlation between prevalence estimates in studies relying on self-reported vs. challenge-confirmed food allergies [23].

The foods most consistently associated with self-reported or in vivo challenge-confirmed allergic manifestations (ranging from OAS to systemic anaphylaxis) in the United States and the European Union are listed in Table 2.

Asero and colleagues recently reported on a series of 1110 adolescent and adult Italian patients (mean age 31 years, range 12–79 years) diagnosed with food allergy based on the history of reaction in the presence of positive skin prick test (SPT) or elevated food-specific serum IgE [24]. Anaphylaxis was reported by 5% of food-allergic individuals, with the most common cause being lipid transfer protein (LTP). LTP is a widely cross-reacting plant panallergen. The offending food for LTP-allergic patients was most often peach, but other foods can also include other members of the Rosaceae family of fruits (apple, pear, cherry, plum, apricot, medlar, almond, and strawberry), tree nuts, corn, rice, beer, tomato, spelt, pineapple, and grape [25][26][27]. Importantly, some foods can trigger anaphylaxis with delayed onset after allergen exposure, as in the case of galactose-α-1,3-galactose (α-gal), in which reactions can occur up to 4 to 6–12 h after allergen ingestion [28].

Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis (FDEIA) is a distinct condition with IgE-mediated mechanisms (such as OAS) that occurs only when the sensitizing food is eaten during the 4 h preceding a physical activity (running, dancing, long walks) or the following hour. The symptoms range from urticaria, angioedema, respiratory, and GI signs to anaphylactic shock [29]. Many different types of foods have been shown to cause FDEIA, including wheat, shellfish, nuts, tomatoes, peanuts, fish, pork, beef, mushrooms, hazelnuts, eggs, peaches, apples, milk, and alcohol, and there are also reports in which the ingestion of two foods together along with exercise are required to trigger a reaction [30]. Reported non-food combination triggers include medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID), cold or warm temperatures, menstrual cycle, pollens, and ingestion of dust mites [31]. The pathophysiological mechanisms that lead to a temporary loss of immune tolerance in FDEIA have not been fully established (see [32] for more details).

2.1.1. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

An accurate clinical and nutritional anamnesis—that is, a detailed medical history documenting the timing and clinical features of the reactions attributed to food—is the mainstay of the diagnostic process of IgE-mediated food allergy, for which it has a positive predictive value close to 100% [33]. A key diagnostic “dogma” in this setting is that results from any in vitro and in vivo tests have no relevance without relatable clinical manifestations. In children, the initial clinical evaluation should include a thorough examination of the growth status and the level of nutrition, as well as research for associated atopic conditions such as atopic dermatitis (AD), allergic rhinitis, or asthma. Relevant for diagnostic purposes are (1) the anamnestic characteristics of the potential food culprit, i.e., type, quantity, raw vs. cooked, previous tolerance; (2) the circumstances potentially favoring the clinical manifestations (exercise, NSAID or alcohol ingestion, viral illnesses); and (3) the host-specific features, such as a history of atopic diseases and/or presence of co-morbidities. Other important issues to investigate are the response to treatment of the allergic reaction and the time passed since the last episode occurred. In vivo diagnostic tools for immediate hypersensitivity include skin prick test (SPT), prick-by-prick (PBP), elimination diet, and oral provocation test, while in vitro diagnostic tools are based on the determination of specific IgE (sIgE) against food proteins (Table 3).

Table 3. In vivo and in vitro tests for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergies [7].

As for the sensitivity and specificity calculated for SPT and for sIgE tests, it should be considered that the results are expressed as “yes/no”, hence not always directly correlated with clinical outcomes. Sensitivity is typically better than specificity, and, in general, increasing the SPT response size or sIgE level correlates with increasing the likelihood of an allergy. Importantly, diagnosis is not based on a single test. Regarding sIgE, the approach of molecular diagnostics called component-resolved diagnosis (CRD) allows us to identify sIgE for specific proteins, or components, in each food. This allows for an individual risk stratification, avoiding unnecessary nutritional and social restrictions. For example, a finding of sIgE vs. LTP exposes individuals to a risk of moderate to severe reactions as this protein is particularly resistant to peptic digestion and to cooking heat, as opposed to the sensitization to a profilin that generally only causes an OAS.

Another third-level in vitro test is the basophil activation test (BAT), a functional assay that measures the ability of IgE to induce the activation of basophils following allergen binding.

The BAT has the potential to closely replicate in vitro type-I hypersensitivity reactions, mimicking the in vivo responses in allergic individuals exposed to the allergen, and thus it can have clinical applications in the diagnosis and control of allergic disease, alongside research applications. The BAT uses flow cytometry to measure the expression of activation markers induced on the surface of basophils following the cross-linking of IgE bound to the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcεRI) by allergen or anti-IgE antibody. The BAT can be performed using whole blood or isolated leukocytes. The BAT has proven more accurate than sIgE determinations in discriminating between clinically allergic patients and tolerant, sensitized subjects, with specificities ranging between 75 and 100% and sensitivities ranging between 77 and 98% in different studies [34][35][36]. Moreover, the BAT can faithfully predict the severity of allergic reactions, in that patients with more severe reactions show a greater proportion of activated basophils and patients reacting to trace amounts of the allergen show a greater basophil threshold sensitivity (a parameter also referred to as CDSENS), i.e., lower concentrations of allergen are sufficient to induce half-maximal expression of basophil activation markers [37][38][39].

The execution of the in vivo tests must be guided by the clinical history reported by the patient and subsequently refined by investigating the sensitization towards the single molecules through the CRD or BAT. An elimination diet for diagnostic purposes is the first in vivo diagnostic step and consists of avoidance of one or more foods suspected of triggering reactions, chosen according to clinical and dietary history coupled with results from appropriate allergy tests such as SPT and serum sIgE levels. The diet must be followed for a set time period, at least until a significant symptom pattern (recurrence or relief) is appreciated: this might be, on average, 2–4 weeks for classical IgE-mediated symptoms, while longer periods, up to 6 weeks, would be required for investigating non-IgE-mediated presentations (see below), as in eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). The diet must be carefully monitored, and the results obtained must be evaluated to establish or refute the diagnosis, to avoid unnecessary dietary restrictions. If the elimination of an allergen from the diet has a limited or unclear effect, the diet should be carefully re-evaluated to test whether alternative potential food allergens were neglected [33]. Lastly, for most food allergy cases, the oral provocation test is required to confirm the diagnosis, in particular as a double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC) protocol, which represents the food allergy diagnostic gold standard [40]. Importantly, oral challenge tests are also essential to monitor the disease course: by demonstrating persistence of reactivity or the acquisition of tolerance, this procedure becomes a major determinant of appropriate dietary indications, ensuring proper nutrition through gradual liberalization in case of newly established tolerance, or an indication of alternative sources of nutrients when strict avoidance is confirmed as necessary.

The clinical management of all forms of food allergy includes both short-term interventions for acute reactions and long-term strategies to minimize the risk of further reactions. Prompt treatment with epinephrine is a cornerstone of therapy of acute severe IgE-mediated food reactions [41]. The patient—or their parents if of pediatric age—should be educated to use epinephrine auto-injectors and other self-medication methods such as antihistamines and steroids for milder reactions. As long-term therapy, the removal of offending foods from the diet (avoidance diet), as well as the ready availability of emergency medication such as epinephrine, are currently the treatment mainstay. However, long-term treatments to prevent reactions to accidental exposure to the food and/or allow its reintroduction in the diet are becoming available. Allergen immunotherapy is an intervention by which an allergic individual is exposed to initially small, gradually increasing quantities of the specific allergen responsible for clinical presentations. The goal is to achieve long-term tolerance or at least sustained unresponsiveness of the immune system, thereby ablating or decreasing, respectively, the probability of an allergic reaction upon allergen re-exposure. In food allergy, major advances have been gained by studies on the efficacy of immunotherapy (IT) approaches, including oral (OIT), sublingual (SLIT), and subcutaneous (SCIT) and epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) [41][42]. Of these, SCIT, which demonstrated a good potential for desensitization in patients with peanut allergy, has been fundamentally abandoned out of concerns for its side effects and overall safety [43][44].

Most data on OIT safety and efficacy come from clinical trials for peanut allergy, the largest of which is a recently published Phase 3 international trial [45][46]. This study showed that six months after achieving a maintenance dose of 300 mg (approximately one peanut), 67.2% of participants receiving active treatment were able to ingest 600 mg or more of peanut protein without dose-limiting symptoms compared to 4% of placebo-treated participants. This and other studies show that under close medical supervision, peanut OIT can be safe and effective for raising the threshold of allergen dose needed to trigger an allergic reaction for many patients. Very recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the oral agent, Peanut Allergen Powder®, for the treatment of peanut allergy in children at least 4 years old. Other approaches to treating peanut allergy include EPIT: results from a Phase 3 international trial were recently published [47]. This approach of daily allergen exposure through the skin via placement of an adhesive patch embedded with allergen resulted in raising the threshold of allergen dose needed to trigger an allergic reaction for some patients. Side effects typically are limited to local patch site reactions. GI symptoms and anaphylaxis are rare [48].

2.1.2. Nutritional Concerns in IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

A prolonged elimination diet, especially when involving major food groups, must be carefully monitored over time as it can lead to impaired nutrition and decreased quality of life. Ideally, these patients should receive adequate support from a dietician with specific expertise in food allergy, especially when managing infants and children with multiple sensitizations, as tolerance can be different for each food and can change over time. Therefore, periodic reassessments are required to test the development of tolerance and thus resolve to liberalize foods. The management of the exclusion diet must be based on the replacement of foods to which one is allergic with the integration of proteins, vitamins, and minerals to prevent deficiency and taking into account medium and long-term sustainability. By comparison, this management can be complex for children and is more straightforward for adults. Although most IgE-mediated allergies resolve between the age of 5 to 10 years [49][50], they represent a major problem for the health and social life of the pediatric population. Epidemiologically, IgE-mediated allergies are more frequent and long-lasting than other forms of immunologic reactions to food, which might resolve on average within the first 3 years of life. It should also be considered that childhood and adolescence are critical periods from a nutritional standpoint, as a growing individual needs quantities and proportions of macro- and micronutrients that vary greatly during the various stages of development.

Poor substitution of basic foods such as milk, eggs, and wheat can result in increased risk of specific macronutrient deficiencies and insufficient intake for all energy needs. Protein deficient diets can also cause poor growth and related morbidities: to the extreme spectrum, Kwashiorkor has been reported in children on allergen elimination diets [51][52]. In children, weight is an indicator for assessing energy and protein intake with respect to health. However, due to protein deficiency there may be overall reduced growth. Cow’s milk is one of the main foods of the pediatric age (indeed the only one in the first months of life in the infant who is not breastfed), but at the same time it is the main allergen common to all forms of food allergies. In case of cow’s milk allergy (CMA), the first choice in the first years of life is replacement with extensively or partially hydrolyzed cow’s milk formulas that a number of studies demonstrate to be nutritionally adequate and well tolerated [53][54][55][56]. If symptoms persist (anaphylaxis, severe GI bleeding, etc.), an amino acid-based formula may be required. Some of these products contain probiotics supplements (such as Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG), which have been shown to reduce symptoms and promote long-term tolerance induction in infants with CMA or other allergies [57].

As the child grows, the use of cow’s milk is sometimes replaced with other animal or vegetable milk source, such as soy-based formula milk. These changes (sometimes prompted by a general “fear of allergies”) can produce harmful nutritional consequences such as calcium and vitamin D deficiencies, or exposure to phytoestrogens and allergic sensitization to soy products [58]. Klemola et al. in a randomized trial found that soy may be less well tolerated than extensively hydrolyzed whey formula, especially among infants younger than 6 months [58]. Two randomized controlled trials suggested that rice hydrolysate formula was well tolerated among infants with CMA and may even reduce the duration of allergy [59][60]. A calcium deficiency is common in children with CMA and must be satisfied with adequate replacement. In 2010, the WAO published “Diagnosis and Rationale for Action Against Cow’s Milk Allergy (DRACMA)”, a set of guidelines that included recommendations for feeding infants and young children with CMA [61]. There are also frequent reports of children developing vitamin D deficiency rickets following dietary restriction [62]. Besides the nutritional needs, it is necessary to consider that adherence to an elimination diet provokes significant stress on young patients and their families, and this leads to restrictions for children and adolescents on attending the school cafeteria, taking school trips, or going at friends’ houses. It must be emphasized that for IgE-mediated food allergies, the elimination diet must be strict, as even small traces of allergen can cause life-threatening reactions. Besides milk, many other food allergy-triggering foods, such as eggs and tree nuts, can be hidden in numerous processed foods that can be easily eaten by an exchange of snacks not carefully evaluated for allergen content by reading the package label. Wheat is the frequent cause of FDEIA in children, in particular in teenage males [15], as adolescents tend to be more physically active through sports or gym activities and rely substantially on wheat and grains for nutrition. In adults, the most common allergens are seafood, peanuts, and tree nuts. Tree nuts include pistachio, pecans, Brazil nuts, cashew, hazelnuts, and walnuts, and people allergic to them often react to more than one variety due to extensive cross-reactivities. Tree nuts have a high content of minerals, proteins, and unsaturated fats, and they carry known beneficial properties for health, such as the cholesterol-lowering properties of walnuts. Although the impact of a necessary avoidance on caloric and nutritional needs can be negligible, the risk of accidental ingestion is substantial as tree nuts are often part of multi-ingredient dishes and present in small quantities or even as a contaminant in many packaged foods; therefore, they are frequently responsible for unexpected reactions due to unintentional ingestion.

A particular group of patients, mostly adults, present reactivity to multiple plant foods through sensitization to LTP, which are plant panallergens whose relevance is mostly limited to the Mediterranean Basin [63][64]. Managing this condition might involve broad nutritional restrictions that are difficult to achieve, in turn leading to severe nutritional deficiency. Often there is only a subclinical sensitization, yet patients must be alerted to the possibility of allergic reactions in the presence of co-factors such as concomitant assumption of alcohol or NSAID or subsequent physical activity.

Lastly, nutritional harms can be caused by erroneous diagnostic procedures leading to inappropriate dietary limitations. In recent years, tests for the diagnosis of food allergy and intolerance not scientifically validated—or even of proven insufficient sensibility and specificity—have gained attention as alternative approaches to identify the causes of signs and symptoms suggestive of food-related manifestations. The use of these tests exposes the patient not only to a possible diagnostic delay of other pathologies but also to serious nutritional imbalances due to the inappropriate elimination of food. This is especially dangerous in children and adolescents where the exclusion of certain foods can lead to growth impairment or serious deficiencies in micronutrients, such as calcium and vitamin D.

2.2. Mixed IgE and Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

Eosinophilic GI diseases (EoGD) share a complex pathogenesis triggered by foods in which an IgE-mediated component is integrated with T cell-mediated immunological mechanisms, characterized by a predominant eosinophilic infiltration of the GI tract. It is a rare, heterogeneous, and poorly defined clinical condition that can involve any segment of the GI tract. Patients with EoGD have variable clinical presentations depending on the affected site and the degree of eosinophilic inflammation. These include EoE, eosinophilic gastritis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, and eosinophilic colitis.

EoE is the most frequent EoGD. EoE is increasingly seen during infancy through adolescence, although it is increasingly being diagnosed in adult age. Failure to thrive is commonly observed in affected children. In older patients, this condition presents clinically with symptoms related to esophageal dysfunction, such as dysphagia, and symptoms mimicking chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Genetic linkage studies, animal models, and the frequency of comorbid allergic disorders link the pathogenesis of EoE with atopy [65]. An elimination diet is a common primary approach, particularly in children, and it might be a treatment option in motivated adults [66][67]. In some cases, EoE appears to be triggered not only by food but also by aeroallergens, while in some instances no clear trigger can be identified [68]. Besides the possible involvement of IgE-dependent immunity, recent studies have also highlighted the presence of IgG4 deposits in the EoE mucosa, hinting at the possible role of this Ig class in the inflammatory response in this condition [69].

AD is a chronically relapsing inflammatory skin disease affecting children and adults and can be present in patients presenting with mixed IgE/cell-mediated food allergies. AD pathogenesis recognizes a complex interaction between skin barrier dysfunction and environmental factors such as irritants, microbes, and allergens. Its clinical presentation and severity vary widely, and diagnosis is not always straightforward, especially in adults. Papules and papulo-vesicles may form large plaques that ooze and crust. They typically affect the face, hands, and extensors, but the scalp, neck, and trunk may also be involved [70].

In some sensitized patients, particularly infants and young children, food allergens can induce urticarial lesions, itching, and eczematous flares, all of which may aggravate AD. The role of food allergens in the pathogenesis and the severity of this condition remains controversial; it is thought to be involved in 30–40% of children with moderate to severe eczema, which generally self-resolves with growth [71].

2.2.1. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of Mixed IgE/Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

Clinical presentations and anamnesis for of EoGD may support a first round of IgE-related diagnostics such as SPT and/or sIgE titers, but often the tests are negative or there is poor clinical correlation; hence, an elimination diet followed by an oral food challenge may be needed to identify the causative food allergen(s) [72][73][74]. Currently, diagnosis is based on endoscopic evaluation and bioptic identification of eosinophilic infiltrate [68], the main pathological feature within the involved GI segment. Only 50% of patients show peripheral eosinophilia [73][75][76][77]. AD is only diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation and history [70]. SPT and sIgE can often identify sensitization to inhaled or food allergens that generally confirm an atopic condition.

In EoGD—where negative or poorly correlated food allergen-related IgE profile are frequently found—an empirical six-food elimination diet is implemented, removing dairy, wheat, egg, soy, nuts, and seafood. In case of no improvement, an amino acid-based elemental diet is adopted. The dietary approach shows good results in upper EoGD, i.e., EoE and eosinophilic gastritis, while it is not as effective in eosinophilic gastroenteritis ad colitis. Once disease remission has been obtained by dietary modification, food groups are slowly reintroduced (at about 3-week intervals for each food group), and endoscopy is performed (approximately every 3 months) to identify sustained remission or disease flare-ups and to document the decreased or absence of mucosal eosinophil infiltration. Another effective therapeutic strategy in EoGD is the use of glucocorticoids, either through specific mucoadherent topical formulation or by swallowing anti-asthmatic inhaled corticosteroids (budesonide, fluticasone, ciclesonide) [78][79][80]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPI) may improve the course of disease in people affected by EoE and eosinophilic gastritis, even when typical gastritis and GERD symptoms are absent [68][79][80]. PPIs used at high dose and continuously can induce remission in about 20–60% of patients affected by EoE with a mechanism that combines their anti-acid and anti-inflammatory activities. Finally, many trials are in progress to evaluate the efficacy of biological drugs in EoGD, one of the best promising being dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody against the interleukin (IL)-4 receptor that inhibits IL-4 and IL-13 signaling, which plays a pivotal role in type 2-driven inflammatory diseases [81].

In AD, the first-line dietary therapy includes a trial of targeted food elimination if sensitization to food is identified by SPT and/or sIgE measurements. However, the correlation with food allergies, while strongest in the first months or years of life, is still relatively low (generally appreciated in no more than 40% of children) [82][83]. Another useful dietary approach in AD seems to be the low-histamine diet, which would help alleviate itching and flare-ups [84]. Besides diet, the therapeutic management of AD is very complex as it includes careful skin care, topical or systemic steroids or immunosuppressants, up to biological drugs (e.g., dupilumab).

2.2.2. Nutritional Concerns in Mixed IgE and Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

Long-term dietary restrictions are the mainstay of treatment in this group of conditions, in particular in patients affected by EoE. The six-food diet involves the avoidance—among others—of foods central in the Western diet as milk and wheat. Wheat in particular is an important source of energy, which should provide between 45 and 65% of the daily energy intake in children. Therefore, in these patients it is essential to provide alternative grains to meet this macronutrient need. Cereals also provide micronutrients (thiamin, niacin, riboflavin, iron, and folic acid) that are not found in fruits and vegetables [85]. Eggs offer excellent quality proteins (they are rich in essential amino acids), vitamins (for example vitamin D) and essential minerals. Legumes provide proteins of good biological quality, although sometimes lacking some essential amino acids. They also contain complex carbohydrates and unsaturated fats, and they are rich in dietary fiber, as well as minerals (such as phosphorus and calcium) and B vitamins. When excluding all these nutrients from the diet, even if temporarily, a proper dietary regimen providing the necessary nutrients from alternative sources is challenging, and patients may clearly benefit from the support of professional nutritionists.

The advantage of dietary approach is to provide effective non-pharmacologic treatment as a long-term disease control option. On the other hand, prolonged food restriction—and, to a greater extent, elemental diets—can pose a risk of nutritional deficiency, can be difficult to manage for patients and families (particularly if nasogastric feeding is required), and can lead to psychological problems and to unnecessary food aversion [86][87]. A relapse upon discontinuation of the diet is common, and long-term EoE recurrence rates while on the same diet remain to be clearly elucidated. This point is salient since adherence to the diet is difficult and can impact the quality of life [88][89]. Another significant concern is due to the lack of non-invasive tests for diagnosis and follow-up of these conditions, which forces affected patients to undergo repeated endoscopies for monitoring the response to therapy.

A targeted food elimination diet guided by SPT or sIgE can improve the course of AD in children. In these cases, cow’s milk and eggs are more frequently avoided, with the implications mentioned above. Soy formulas can be used for the replacement of cow’s milk but do not protect against eczema development. A low-histamine diet is also advised, whose associated nutritional concerns are discussed in Section 3.1.

2.3. Non-IgE-Mediated Food Allergy

This group includes celiac disease (CD), food protein-induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES), food protein-induced enteropathy (FPE), and food protein-induced allergic proctocolitis (FPIAP) [1][33]. CD is an immune-mediated disorder triggered by dietary gluten, a protein found in cereals such as wheat, rye, and barley. CD is strongly dependent on the genetic background. The disorder is characterized by a small intestinal enteropathy leading to GI as well as extra-GI manifestations and the production of auto-antibodies besides anti-gliadin antibodies, such as anti-endomysium and anti-tissue transglutaminase (TTG) antibodies [90]. The measurement of serum anti-TTG antibodies is very useful for the diagnosis and follow-up of these patients, since they disappear in patients following a gluten-free diet. The seroprevalence of CD was recently estimated at 1.4% worldwide, ranging from 1.1 to 1.8% across geographical areas [91]. Besides CD (not further discussed in this review), this group of food protein-induced diseases have characteristically an early onset (within the first year of life) and GI clinical manifestations. Despite the significant, often dramatic clinical manifestations during the acute phases, the prognosis is favorable, with the majority of patients resolving by age 3–5 years. In acute FPIES, repetitive vomiting, lethargy, and paleness appear from 30 to 240 min after taking the triggering food, which is most commonly cow’s milk, soy, cereals, fish, eggs, poultry/meats, fruit, legumes, or other vegetables. Reactions to multiple foods are not uncommon. Diarrhea can also follow 5 to 10 h later, although this is a less common feature (25–50%). Symptoms may be quite severe, with up to 15% patients experiencing hemodynamic instability. Chronic FPIES typically occurs with persistent exposure to cow’s milk or soy-based formula, and it presents with chronic watery diarrhea (occasionally with blood or mucus), intermittent emesis, abdominal distension, and poor weight gain [92][93][94][95]. Although FPIES generally occurs in early infancy, adult-onset FPIES is now also being increasingly recognized, most frequently triggered by seafood [96][97][98][99]. Finally, a rare occurrence of symptomatic fetal and neonatal FPIES has recently been reported, due to intrauterine sensitization [100][101]. In FPE, symptoms develop in infants shortly after the introduction of cow’s milk in the diet, with chronic diarrhea and features of malabsorption such as steatorrhea and failure to thrive. Vomiting is also frequently reported. FPE is usually transient and typically resolves by 1–2 years of age, as in the case of FPIAP, although in the latter case there is an increased risk of functional GI disorders. FPIAP most often occurs in exclusively breastfed infants within the first weeks of life, because of indirect exposure to maternal dietary protein via breastmilk, although direct feeding can also trigger symptoms. These infants present with bloody, loose stools, sometimes with mucus, but the infants generally appear in well-being [102].

2.3.1. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Management of Non-IgE-Mediated Food Protein-Induced Allergy

Diagnosis of food protein-induced diseases relies, for the most part, on the clinical picture with the exception of FPE, in which histological confirmation is usually required when young infants (<9 months) present symptoms of vomiting and intestinal malabsorption [103]. The diagnosis of FPIES and FPIAP relies on the appreciation of a constellation of concordant symptoms coupled with their resolution upon dietary restrictions of the offending food. An oral food challenge should be strongly considered when only a single episode has occurred, or when the causative food remains elusive, preferably with the documented recurrence of symptoms when foods are re-introduced. Two therapeutic strategies can be adopted, depending on the severity of the symptoms and on the quality of triggering foods: a “bottom-up approach”, in which only causal foods are eliminated, and a “top-down approach”, warranted in most severe cases where failure to thrive and dehydration are prominent. This latter approach consists of an initial avoidance of a wide variety of foods, sometimes starting with an elemental diet, followed by the sequential reintroduction of individual foods. Extensively hydrolyzed cow’s milk formula and amino acid-based formula (AAF) may be useful long-term management strategies for infants with IgE- or non-IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy (but only 10–20% of the latter patients require AAF). Usually 50% of infants with FPIES caused by cow’s milk develop tolerance by 1 year and 90% by 3 years [104]. FPIES caused by solid foods appears to persist for longer [92]. Sometimes FPIES can arise during breastfeeding; in these cases, if a food trigger is identified, the mother has to follow an elimination diet.

2.3.2. Nutritional Concerns in Non-IgE-Mediated Food Protein-Induced Allergy

The three most common foods causing FPIES are milk, soy, and rice. Rare triggers include other cereals and legumes (peanut, green pea, string bean), sweet potato, squash, carrot, egg white, chicken, turkey, fish, and banana [105]. When milk is the trigger food, it is important to supplement calcium and vitamin D. FPIAP is also typically induced by cow’s milk protein, which requires its elimination from the child’s diet or from the mother’s diet when breastfed infants are affected. Spontaneous resolution is acquired within 1–2 years of age. The most common triggers for FPE are cow’s milk, soy, and rarely chicken, rice and fish [1]; this condition rarely persists beyond 3 years of age. Therefore, a strict surveillance for potential nutritional issues is only required for a limited period, and during follow-up visits it is key to address unnecessary restrictions of milk and dairy products that could further compromise health and quality of life, which is above and beyond the psychological price imposed by the prescribed dietary restriction [106][107].

2.4. Pathophysiology of Immunologic Adverse Reactions to Food

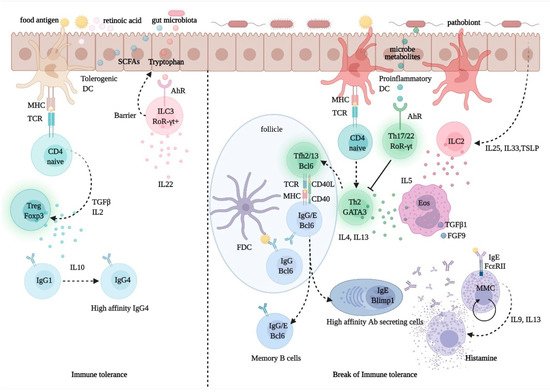

Despite intensive research efforts over the past several years, the management of allergic diseases and chronic inflammatory conditions, which are on a steady rise in both prevalence and severity, still faces unmet challenges. Central to the pathogenesis of these diseases is the development of a T helper (Th) 2-biased, allergen-specific immune response, characterized by IgE synthesis, eosinophilia, and target organ hyperresponsiveness, and it results from a complex interplay of genetically controlled and environmental factors (Figure 3). The hygiene hypothesis, invoked to explain the disproportionate rise in prevalence of allergic and other inflammatory disorders over the past 40 years, provides a conceptual framework to understanding how a modified environment may pave the way for abnormal, imbalanced immune reactivity in predisposed individuals [108]. However, the factors and pathways mediating predisposition to allergic diseases, collectively referred to as atopy, remain elusive. It is thought that the sign and strength of an immune response to a given antigen (Ag) may reflect an intrinsic, predetermined bias in Ag-specific T cells, yet there is no definitive evidence in support of this theory. In fact, evidence suggests that exposure of non-allergic individuals to allergen may not result in allergen-specific protective, Th1-directed responses, and may instead result in specific tolerance or no response at all [109]. This points to the involvement of an additional or alternative checkpoint(s) in Ag recognition, which may affect immune responses by controlling Ag availability and processing.

Figure 3. Regulation of immune tolerance in the gut mucosa. Upon processing of dietary fibers, bacterial metabolites, such as short chain fatty acids (SCFA) and retinoic acid (RA), direct the development and function of FoxP3+ Treg cells via the interaction with gut epithelial cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells (DCs) with naïve CD4+ T cells. The activation and expansion of Treg cells promote the production of the immune regulatory cytokine, IL-10, which foster IgG1 to IgG4 B-cell class switching. Allergen-specific IgG4 B cells produce high-affinity antibodies for food allergens, preventing allergen interactions with mast cell-bound IgE. Microbiota-delivered factors, such as tryptophan-indole catabolites, may directly activate ROR-γt+ type-3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), via the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), and induce the production of IL-22, a cytokine promoting gut epithelial regeneration and barrier integrity. Conversely, upon exposure to pathobionts, DCs and epithelial cells receive danger signals and release cytokines, such as IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP); these promote the activation and expansion of ILC2s, which express Th2 cytokines, such as IL4, IL-5, and IL13. While IL-5 promotes eosinophil activation and differentiation and the production of profibrotic factors, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-9, IL-13 produced by Th2 cells and T follicular helper (Tfh) 13 cells, is critical for the expression of high-affinity antigen-specific IgE. IgE antibodies interact with FcεRI on mast cells and upon exposure to allergen triggers degranulation and release of histamine, which causes allergy and inflammation.

Under normal conditions, only minimal amounts of Ag can cross mucosal barriers through the paracellular pathway, a process typically associated with the development of immune tolerance. Ag exposure of inappropriate duration or magnitude may lead to immune-mediated diseases in genetically susceptible subjects. In a few instances, this has been suggested to reflect the intrinsic properties of the antigenic protein. Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus (Der p) 1 from house dust mite (HDM), one of the most common indoor aeroallergens, has long been shown to be able to disrupt intercellular tight junctions (TJ) and increase Ag trafficking through bronchial epithelial monolayers [110]. This property, and in general the ability to induce epithelial effector functions, is shared with other allergens—including certain food allergens—and less specific triggers such as detergents and microplastics [111][112][113]. However, allergic sensitization may be facilitated in the presence of intrinsic barrier defects, as evidenced in genetic studies showing the significant association of filaggrin (FLG) loss-of-function mutants, impaired skin barrier function, and the development of allergic disease [114]. Increasing evidence suggests that epicutaneous sensitization may in fact promote the subsequent development of allergic diseases, especially food allergy, in children with AD, thus contributing to the progression of the atopic march [115][116].

As amply documented in a wealth of studies conducted over the past 20 years, the composition and diversity of the microbial communities lining all body surfaces, collectively referred to as microbiota, represent a major, critical variable in the regulation of barrier competence and adaptive and innate responses [117][118]. The gut microbiota is successfully seeded early in life, by colonization from maternal vaginal and breast communities at birth and during lactation [119]. Subsequently, throughout adult life, the microbiota is significantly influenced by dietary habits [120]. Host-microbiota interactions are known to have a critical impact on multiple components of the immune system, contributing to immune homeostasis and susceptibility to infectious and inflammatory diseases. Allergic inflammation resulting from skewed activation of Th2 clones is typically enhanced in germ-free animals, suggesting a major role for gut colonization in the development of balanced Th1/Th2 responses [121]. Likewise, reduced Th1 responses and an increased predisposition to develop allergic disease can be observed in infants delivered by cesarean section, associated with a delayed gut colonization of symbiont species and a less diverse microbial community [122]. In fact, the risk of developing unbalanced immune responses in infancy and childhood, resulting in allergic and autoimmune disease, has also been linked to the maternal diet, particularly during pregnancy and lactation. In support of this theory, recent studies have documented the increased levels of food allergen-specific IgE and IgG antibodies in the offspring of mothers who were prescribed gestational-targeted or exclusion diets [123], and, conversely, an overall reduced risk for immune dysfunction was found following maternal supplementation with probiotics (reviewed in [124]). These overall studies provide factual evidence in support of the hygiene hypothesis, whereby exposure to declining environmental biodiversity, by adversely affecting the human microbiota and its central functions in immune regulation, would primarily account for the rising prevalence of allergic and other chronic inflammatory diseases [125][126].

Highlighted in several studies are the interactions of FoxP3+ T regulatory (Treg) cells, a CD4+ T-cell subset critically involved in immune homeostasis and tolerance, with microbiota-delivered signals. A sufficiently diverse microbial community may promote the activation and expansion of Treg cells and the production of the immune regulatory cytokine, IL-10, via the interaction of certain bacterial components with Toll-like receptors (TLR) or other pattern recognition receptors (PRR) [127]. Bacterial metabolites, e.g., butyrate and other short chain fatty acids (SCFA) generated upon the processing of dietary fibers, can also direct the development and function of Treg cells via the interaction with gut epithelial cells and dendritic cells and the induction of immunomodulatory mediators such as vitamin A metabolite retinoic acid (RA) [128][129]. As documented in animal models of food allergy, concentrations of butyrate, such as those measured in mature human milk, are sufficient to promote gut barrier integrity and IL-10 production, reduce the allergic response, and enhance the desensitizing effect of allergen immunotherapy (AIT) [130][131]. These findings are invoked to explain the beneficial anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic effects of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium probiotic mixtures and of a high-fiber diet [120][128][130][132].

A connection between diet, gut microbiota composition, and allergic inflammation is postulated in several studies [133][134]. Studies in germ-free mice demonstrated that microbiota-delivered factors can regulate Th2-driven immunity through the induction of Th17 cells and of a subset of Treg cells expressing the Th17 signature factor, retinoid-related orphan receptor (ROR)-γt [135]. Lactobacillus strains and other symbiotic species, through the production of tryptophan-indole catabolites, may directly activate these cells, as well as ROR-γt+ type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), via the aryl-hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), and induce the production of IL-22, a cytokine-promoting gut epithelial regeneration, barrier integrity, and the secretion of antimicrobial peptides [132][136]. In addition, IL-1β produced by intestinal macrophages sensing microbial signals can induce the release of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) from nearby ROR-γt+ ILC3, which in turn upregulates RA and IL-10 production from dendritic cells and macrophages, further contributing in the maintenance of tolerance to dietary antigens [137].

The central role of innate immunity in the integration of the environmental signals involved in the development and maintenance of natural tolerance to foods and other antigens has emerged convincingly in recent years. As shown in a cohort study of egg-allergic infants, a distinctive cytokine signature is detected early in life in circulating monocytes and dendritic cells, which is predictive of persistent food allergy in childhood [138]. On the other hand, innate immune profiles in children eventually outgrowing their allergy were directly related to serum levels of vitamin D, further stressing the importance of this nutrient in the development of natural tolerance in childhood [138]. Cytokines released by dendritic cells and epithelial cells upon exposure to pathobiont-delivered danger signals, including IL-25, IL-33, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP)—collectively referred to as alarmins—directly contribute to allergic inflammation via the direct activation and expansion of ILC2, an innate lymphoid subset that expresses substantial amounts of Th2 cytokines [139]. The pathophysiologic role of ILC2 in allergic disease has been demonstrated in several models [140][141][142]. These cells, either on their own or in a complex amplifying loop with Th2 cells, may promote and enhance the expression of food-specific IgE in switched and unswitched B cells mainly via the production of IL-4 and IL-13 [141][142][143].

The critical role of IL-13 and related Th2 cytokines in allergic sensitization and its clinical manifestations is emphasized in a recent study documenting that a subset of IL-13-producing T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, termed Tfh13, is critically required for the expression of high-affinity specific IgE and the subsequent development of severe anaphylaxis [144]. Tfh cells, a specialized CD4+ T-cell subset defined by expression of the nuclear factor Bcl6 and of the cytokine, IL-21, are key players for the development of switched, memory B cells and plasma cells in germinal centers [145]. While both IL-13 and IL-4 contribute to IgE class-switch recombination and allergic inflammation in part via the interaction with shared receptors, their expression is driven by diverging mechanisms, possibly reflecting their unique involvement in distinct aspects of the allergic response [146][147][148]. Regardless, lineage tracing experiments conclusively demonstrated that in most instances, the switched, allergen-specific IgG+ B cells are the precursors of IgE-expressing B cells and IgE antibody-secreting plasma cells [149]. In situ IgE class switching and IgE production have been documented in the respiratory and gastroenteric mucosa in response to such environmental signals, as allergen exposure and microbial superantigens [150][151]. Importantly, single-cell transcriptomic analyses reveal virtually absent IgE+ memory B cells in most individuals, whereby most IgE-producing cells are represented by plasma cells [152]. Taken together, these findings suggest that persisting levels of specific IgE in patients with chronic allergies may only be ensured by continuous plasma blast generation via sequential switching from an IgG+ memory pool [153][154].

A marked reduction in serum IgE titers was documented in AD patients treated with dupilumab, a monoclonal antibody that blocks IL-4 and IL-13 interaction with their shared receptor [155]. This is consistent with the idea that a significant proportion of IgE are secreted from newly switched, short-lived plasma blasts, and that interfering with Th2 or ILC2 activation and downstream effector signals might hence greatly contribute to restoring tolerance to common allergens. Current AIT protocols, including OIT, are indeed aimed at counteracting these responses via the induction of allergen-specific Treg cells [156]. However, a prospective decrease in specific IgE levels is not a sufficient predictor of clinical outcome in AIT protocols (reviewed in [157]), whereas a rise in other antibody classes, namely IgA, IgG1, and especially IgG4, is more consistently observed [158][159]. Switching to IgG4 is promoted by IL-10, a cytokine produced at higher levels in patients receiving AIT [160]. Such allergen-specific IgG4 undergo increased somatic mutation relative to IgE in these patients, resulting in the expression of antibodies with higher affinity for allergens and is hence more effective at preventing allergen interactions with mast cell-bound IgE [161].

IL-10-producing, immunosuppressive B regulatory cells (Breg) have been recently demonstrated, which were found to be expanded and contribute to peripheral allergen tolerance in patients receiving AIT [162][163]. Interestingly, a subset of Breg cells, termed BR1, were found to be the exclusive source of specific IgG4 and a precursor of IgG4-secreting plasma blasts, in subjects displaying spontaneous or AIT-acquired tolerance to allergen [164]. The recently discovered mutual interactions of effector and regulatory B cells with microbiota components further stress the relative importance of these cells in immune homeostasis in the gut and other mucosal surfaces and the pathophysiology of food allergy and other diseases associated with imbalanced, aberrant responses to environmental antigens.

While most immune-mediated food allergies are associated with predominant Th2-driven, IgE-mediated responses, the development of variably related conditions as eosinophilic esophagitis, FPIES, FPE, FPIAP, and CD, recognizes distinct and relatively complex immune mechanisms. EoE is also mediated by a prevalent, Th2-biased immune response [165]. In particular, elevated levels of IL-5 promote eosinophil differentiation and trafficking to the esophagus [166] and, together with IL-9, are responsible for the progressive eosinophilia and mastocytosis typically observed in the esophageal mucosa in affected patients. Activated eosinophils and mast cells can in turn produce profibrotic factors (such as the transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 and the fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-9), which cause remodeling of the esophageal epithelium and subepithelium and are responsible for the characteristic symptoms and complications of this condition [167]. However, the association of EoE’s clinical picture with IgE-dominated specific responses to food is not entirely clear. In some cases, EoE symptoms also appear to be triggered by airborne allergens, and in quite a few cases no clear trigger can be identified [68]. Moreover, recent studies also highlighted the presence of IgG4 deposits in the esophageal mucosa, suggesting their possible contribution to the inflammatory response in EoE [69].

In FPIES, a specific T-cell response to causative food antigens leads to TNF-α secretion, which initiates the systemic activation of monocytes, eosinophils, neutrophils, and natural killer cells, resulting in inflammation and increased permeability of the GI mucosa [168][169]. In FPE, the jejunal mucosa is damaged by infiltrating T cells that mostly exhibit a cytotoxic, CD8+ effector phenotype and a γδ TCR, causing malabsorption [170]. FPIAP is characterized by a dense eosinophilic infiltration of the rectosigmoid mucosa and typically affects breastfed infants, suggesting the possible role of immunologic components found in breastmilk, such as secretory Igs specific for dietary proteins [171]. Finally, in CD, deamidated α-gliadin-derived peptides are presented by HLA-DQ2/DQ8 complexes of APC in genetically predisposed individuals. Following activation, α-gliadin-specific T cells migrate from the lamina propria into the subepithelial area and begin to produce various pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IFN-γ and TNF-α. Activated cytotoxic T cells also produce molecules, such as Fas ligand and granzymes, which promote apoptosis of nearby enterocytes. These events combined trigger an extensive immune reaction that causes pathological tissue alterations, resulting in damage of the small intestinal mucosa, villous atrophy, and malabsorption [172]. The ensuing activation of B cells leads to the production of anti-gliadin, anti-endomysium, and anti-TTG antibodies [173]. The presence of anti-TTG antibodies in serum is very useful for diagnosis and for times during the follow-up since they disappear from the serum of patients when they are on a gluten-free diet. However, it is unclear whether they are responsible for the damage to the mucosa or are rather its consequence [172].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13051638

References

- Boyce, J.A.; Assa’ad, A.; Burks, A.W.; Jones, S.M.; Sampson, H.A.; Wood, R.A.; Plaut, M.; Cooper, S.F.; Fenton, M.J.; Arshad, S.H.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the united states: Summary of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 126, 1105–1118.

- Warren, C.M.; Jiang, J.; Gupta, R.S. Epidemiology and burden of food allergy. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2020, 20, 6.

- Gupta, R.S.; Warren, C.M.; Smith, B.M.; Jiang, J.; Blumenstock, J.A.; Davis, M.M.; Schleimer, R.P.; Nadeau, K.C. Prevalence and severity of food allergies among us adults. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e185630.

- Sicherer, S.H.; Warren, C.M.; Dant, C.; Gupta, R.S.; Nadeau, K.C. Food allergy from infancy through adulthood. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 1854–1864.

- Santos, A.F. Prevention of food allergy: Can we stop the rise of ige mediated food allergies? Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 21, 195–201.

- Wolf, W.A.; Jerath, M.R.; Sperry, S.L.; Shaheen, N.J.; Dellon, E.S. Dietary elimination therapy is an effective option for adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 12, 1272–1279.

- Onyimba, F.; Crowe, S.E.; Johnson, S.; Leung, J. Food allergies and intolerances: A clinical approach to the diagnosis and management of adverse reactions to food. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021.

- Ho, M.H.; Wong, W.H.; Chang, C. Clinical spectrum of food allergies: A comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 46, 225–240.

- Sampson, H.A.; Munoz-Furlong, A.; Campbell, R.L.; Adkinson, N.F., Jr.; Bock, S.A.; Branum, A.; Brown, S.G.; Camargo, C.A., Jr.; Cydulka, R.; Galli, S.J.; et al. Second symposium on the definition and management of anaphylaxis: Summary report--second national institute of allergy and infectious disease/food allergy and anaphylaxis network symposium. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2006, 47, 373–380.

- Sampson, H.A. Update on food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 805–819.

- Waserman, S.; Watson, W. Food allergy. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2011, 7, S7.

- Price, A.; Ramachandran, S.; Smith, G.P.; Stevenson, M.L.; Pomeranz, M.K.; Cohen, D.E. Oral allergy syndrome (pollen-food allergy syndrome). Dermatitis 2015, 26, 78–88.

- Simons, F.E.; Ardusso, L.R.; Bilo, M.B.; El-Gamal, Y.M.; Ledford, D.K.; Ring, J.; Sanchez-Borges, M.; Senna, G.E.; Sheikh, A.; Thong, B.Y.; et al. World allergy organization guidelines for the assessment and management of anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ. J. 2011, 4, 13–37.

- Cardona, V.; Ansotegui, I.J.; Ebisawa, M.; El-Gamal, Y.; Fernandez Rivas, M.; Fineman, S.; Geller, M.; Gonzalez-Estrada, A.; Greenberger, P.A.; Sanchez Borges, M.; et al. World allergy organization anaphylaxis guidance 2020. World Allergy Organ. J. 2020, 13, 100472.

- Cianferoni, A.; Muraro, A. Food-induced anaphylaxis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2012, 32, 165–195.

- Bansal, A.S.; Chee, R.; Nagendran, V.; Warner, A.; Hayman, G. Dangerous liaison: Sexually transmitted allergic reaction to brazil nuts. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2007, 17, 189–191.

- Liccardi, G.; Caminati, M.; Senna, G.; Calzetta, L.; Rogliani, P. Anaphylaxis and intimate behaviour. Curr. Opin Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 17, 350–355.

- Lyons, S.A.; Burney, P.G.J.; Ballmer-Weber, B.K.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Barreales, L.; Clausen, M.; Dubakiene, R.; Fernandez-Perez, C.; Fritsche, P.; Jedrzejczak-Czechowicz, M.; et al. Food allergy in adults: Substantial variation in prevalence and causative foods across europe. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 1920–1928.e1911.

- Freye, H.B.; Esch, R.E.; Litwin, C.M.; Sorkin, L. Anaphylaxis to the ingestion and inhalation of tenebrio molitor (mealworm) and zophobas morio (superworm). Allergy Asthma Proc. 1996, 17, 215–219.

- Gautreau, M.; Restuccia, M.; Senser, K.; Weisberg, S.N. Familial anaphylaxis after silkworm ingestion. Prehosp. Emerg. Care 2017, 21, 83–85.

- De Pasquale, T.; Buonomo, A.; Illuminati, I.; D’Alo, S.; Pucci, S. Recurrent anaphylaxis: A case of ige-mediated allergy to carmine red (e120). J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 25, 440–441.

- de Gier, S.; Verhoeckx, K. Insect (food) allergy and allergens. Mol. Immunol. 2018, 100, 82–106.

- Nwaru, B.I.; Hickstein, L.; Panesar, S.S.; Roberts, G.; Muraro, A.; Sheikh, A.; Allergy, E.F.; Anaphylaxis Guidelines, G. Prevalence of common food allergies in europe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy 2014, 69, 992–1007.

- Asero, R.; Antonicelli, L.; Arena, A.; Bommarito, L.; Caruso, B.; Colombo, G.; Crivellaro, M.; De Carli, M.; Della Torre, E.; Della Torre, F.; et al. Causes of food-induced anaphylaxis in italian adults: A multi-centre study. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2009, 150, 271–277.

- Romano, A.; Fernandez-Rivas, M.; Caringi, M.; Amato, S.; Mistrello, G.; Asero, R. Allergy to peanut lipid transfer protein (ltp): Frequency and cross-reactivity between peanut and peach ltp. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009, 41, 106–111.

- Asero, R.; Mistrello, G.; Amato, S.; Roncarolo, D.; Martinelli, A.; Zaccarini, M. Peach fuzz contains large amounts of lipid transfer protein: Is this the cause of the high prevalence of sensitization to ltp in mediterranean countries? Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 38, 118–121.

- Asero, R.; Mistrello, G.; Roncarolo, D.; Amato, S. Relationship between peach lipid transfer protein specific ige levels and hypersensitivity to non-rosaceae vegetable foods in patients allergic to lipid transfer protein. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004, 92, 268–272.

- Wilson, J.M.; Schuyler, A.J.; Workman, L.; Gupta, M.; James, H.R.; Posthumus, J.; McGowan, E.C.; Commins, S.P.; Platts-Mills, T.A.E. Investigation into the alpha-gal syndrome: Characteristics of 261 children and adults reporting red meat allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2019, 7, 2348–2358.e2344.

- Beaudouin, E.; Renaudin, J.M.; Morisset, M.; Codreanu, F.; Kanny, G.; Moneret-Vautrin, D.A. Food-dependent exercise-induced anaphylaxis--update and current data. Eur. Ann. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2006, 38, 45–51.

- Povesi Dascola, C.; Caffarelli, C. Exercise-induced anaphylaxis: A clinical view. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2012, 38, 43.

- Castells, M.C.; Horan, R.F.; Sheffer, A.L. Exercise-Induced anaphylaxis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2003, 3, 15–21.

- Turnbull, J.L.; Adams, H.N.; Gorard, D.A. Review article: The diagnosis and management of food allergy and food intolerances. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 41, 3–25.

- Muraro, A.; Werfel, T.; Hoffmann-Sommergruber, K.; Roberts, G.; Beyer, K.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Cardona, V.; Dubois, A.; duToit, G.; Eigenmann, P.; et al. Eaaci food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines: Diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy 2014, 69, 1008–1025.

- Ocmant, A.; Mulier, S.; Hanssens, L.; Goldman, M.; Casimir, G.; Mascart, F.; Schandene, L. Basophil activation tests for the diagnosis of food allergy in children. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2009, 39, 1234–1245.

- Santos, A.F.; Douiri, A.; Becares, N.; Wu, S.Y.; Stephens, A.; Radulovic, S.; Chan, S.M.; Fox, A.T.; Du Toit, G.; Turcanu, V.; et al. Basophil activation test discriminates between allergy and tolerance in peanut-sensitized children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2014, 134, 645–652.

- Rubio, A.; Vivinus-Nebot, M.; Bourrier, T.; Saggio, B.; Albertini, M.; Bernard, A. Benefit of the basophil activation test in deciding when to reintroduce cow’s milk in allergic children. Allergy 2011, 66, 92–100.

- Song, Y.; Wang, J.; Leung, N.; Wang, L.X.; Lisann, L.; Sicherer, S.H.; Scurlock, A.M.; Pesek, R.; Perry, T.T.; Jones, S.M.; et al. Correlations between basophil activation, allergen-specific ige with outcome and severity of oral food challenges. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015, 114, 319–326.

- Santos, A.F.; Du Toit, G.; Douiri, A.; Radulovic, S.; Stephens, A.; Turcanu, V.; Lack, G. Distinct parameters of the basophil activation test reflect the severity and threshold of allergic reactions to peanut. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015, 135, 179–186.

- Chinthrajah, R.S.; Purington, N.; Andorf, S.; Rosa, J.S.; Mukai, K.; Hamilton, R.; Smith, B.M.; Gupta, R.; Galli, S.J.; Desai, M.; et al. Development of a tool predicting severity of allergic reaction during peanut challenge. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018, 121, 69–76.e62.

- Sampson, H.A.; van Wijk, R.G.; Bindslev-Jensen, C.; Sicherer, S.; Teuber, S.S.; Burks, A.W.; Dubois, A.E.; Beyer, K.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Spergel, J.M.; et al. Standardizing double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges: American academy of allergy, asthma & immunology-european academy of allergy and clinical immunology practall consensus report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 130, 1260–1274.

- Muraro, A.; Halken, S.; Arshad, S.H.; Beyer, K.; Dubois, A.E.; Du Toit, G.; Eigenmann, P.A.; Grimshaw, K.E.; Hoest, A.; Lack, G.; et al. Eaaci food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy 2014, 69, 590–601.

- Lack, G. Clinical practice. Food allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1252–1260.

- Nelson, H.S.; Lahr, J.; Rule, R.; Bock, A.; Leung, D. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1997, 99, 744–751.

- Oppenheimer, J.J.; Nelson, H.S.; Bock, S.A.; Christensen, F.; Leung, D.Y. Treatment of peanut allergy with rush immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1992, 90, 256–262.

- PALISADE Group of Clinical Investigators; Vickery, B.P.; Vereda, A.; Casale, T.B.; Beyer, K.; du Toit, G.; Hourihane, J.O.; Jones, S.M.; Shreffler, W.G.; Marcantonio, A.; et al. Ar101 oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1991–2001.

- Cianferoni, A.; Hanna, E.; Lewis, M.; Alfaro, M.K.; Corrigan, K.; Buonanno, J.; Datta, R.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.; Spergel, J. Safety review of year 1 oral immunotherapy clinic: Multifood immunotherapy in real-world setting. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, AB245.

- Fleischer, D.M.; Greenhawt, M.; Sussman, G.; Begin, P.; Nowak-Wegrzyn, A.; Petroni, D.; Beyer, K.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.; Hebert, J.; Hourihane, J.O.; et al. Effect of epicutaneous immunotherapy vs. placebo on reaction to peanut protein ingestion among children with peanut allergy: The pepites randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019, 321, 946–955.

- Kulis, M.; Smeekens, J.; Kim, E.; Zarnitsyn, V.; Patel, S. Peanut protein-loaded microneedle patches are immunogenic and distinct from subcutaneous delivery. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, AB237.

- Sicherer, S.H.; Sampson, H.A. Food allergy: A review and update on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 141, 41–58.

- Sicherer, S.H.; Wood, R.A.; Stablein, D.; Burks, A.W.; Liu, A.H.; Jones, S.M.; Fleischer, D.M.; Leung, D.Y.; Grishin, A.; Mayer, L.; et al. Immunologic features of infants with milk or egg allergy enrolled in an observational study (consortium of food allergy research) of food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, 1077–1083.e1078.

- Novembre, E.; Leo, G.; Cianferoni, A.; Bernardini, R.; Pucci, N.; Vierucci, A. Severe hypoproteinemia in infant with ad. Allergy 2003, 58, 88–89.

- Mori, F.; Serranti, D.; Barni, S.; Pucci, N.; Rossi, M.E.; de Martino, M.; Novembre, E. A kwashiorkor case due to the use of an exclusive rice milk diet to treat atopic dermatitis. Nutr. J. 2015, 14, 83.

- Niggemann, B.; von Berg, A.; Bollrath, C.; Berdel, D.; Schauer, U.; Rieger, C.; Haschke-Becher, E.; Wahn, U. Safety and efficacy of a new extensively hydrolyzed formula for infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2008, 19, 348–354.

- Galli, E.; Chini, L.; Paone, F.; Moschese, V.; Knafelz, D.; Panel, P.; Emanuele, E.; Palermo, D.; Di Fazio, A.; Rossi, P. Clinical comparison of different replacement milk formulas in children with allergies to cow’s milk proteins. 24-month follow-up study. Minerva Pediatr. 1996, 48, 71–77.

- Muraro, M.A.; Giampietro, P.G.; Galli, E. Soy formulas and nonbovine milk. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002, 89, 97–101.

- Halken, S.; Host, A.; Hansen, L.G.; Osterballe, O. Safety of a new, ultrafiltrated whey hydrolysate formula in children with cow milk allergy: A clinical investigation. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 1993, 4, 53–59.

- Berni Canani, R.; Nocerino, R.; Terrin, G.; Coruzzo, A.; Cosenza, L.; Leone, L.; Troncone, R. Effect of lactobacillus gg on tolerance acquisition in infants with cow’s milk allergy: A randomized trial. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2012, 129, 580–582.

- Klemola, T.; Vanto, T.; Juntunen-Backman, K.; Kalimo, K.; Korpela, R.; Varjonen, E. Allergy to soy formula and to extensively hydrolyzed whey formula in infants with cow’s milk allergy: A prospective, randomized study with a follow-up to the age of 2 years. J. Pediatr. 2002, 140, 219–224.

- Reche, M.; Pascual, C.; Fiandor, A.; Polanco, I.; Rivero-Urgell, M.; Chifre, R.; Johnston, S.; Martin-Esteban, M. The effect of a partially hydrolysed formula based on rice protein in the treatment of infants with cow’s milk protein allergy. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 21, 577–585.

- Terracciano, L.; Bouygue, G.R.; Sarratud, T.; Veglia, F.; Martelli, A.; Fiocchi, A. Impact of dietary regimen on the duration of cow’s milk allergy: A random allocation study. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2010, 40, 637–642.

- Fiocchi, A.; Brozek, J.; Schunemann, H.; Bahna, S.L.; von Berg, A.; Beyer, K.; Bozzola, M.; Bradsher, J.; Compalati, E.; Ebisawa, M.; et al. World allergy organization (wao) diagnosis and rationale for action against cow’s milk allergy (dracma) guidelines. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2010, 21, 1–125.

- Fox, A.T.; Du Toit, G.; Lang, A.; Lack, G. Food allergy as a risk factor for nutritional rickets. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2004, 15, 566–569.

- Salcedo, G.; Sanchez-Monge, R.; Diaz-Perales, A.; Garcia-Casado, G.; Barber, D. Plant non-specific lipid transfer proteins as food and pollen allergens. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2004, 34, 1336–1341.

- Breiteneder, H.; Mills, C. Nonspecific lipid-transfer proteins in plant foods and pollens: An important allergen class. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005, 5, 275–279.

- O’Shea, K.M.; Aceves, S.S.; Dellon, E.S.; Gupta, S.K.; Spergel, J.M.; Furuta, G.T.; Rothenberg, M.E. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 333–345.

- Lieberman, J.A.; Morotti, R.A.; Konstantinou, G.N.; Yershov, O.; Chehade, M. Dietary therapy can reverse esophageal subepithelial fibrosis in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: A historical cohort. Allergy 2012, 67, 1299–1307.

- Greenhawt, M.; Aceves, S.S.; Spergel, J.M.; Rothenberg, M.E. The management of eosinophilic esophagitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2013, 1, 332–340.

- Dellon, E.S.; Hirano, I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 319–332.e313.

- Clayton, F.; Fang, J.C.; Gleich, G.J.; Lucendo, A.J.; Olalla, J.M.; Vinson, L.A.; Lowichik, A.; Chen, X.; Emerson, L.; Cox, K.; et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with igg4 and not mediated by ige. Gastroenterology 2014, 147, 602–609.

- Fishbein, A.B.; Silverberg, J.I.; Wilson, E.J.; Ong, P.Y. Update on atopic dermatitis: Diagnosis, severity assessment, and treatment selection. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2020, 8, 91–101.

- Rowlands, D.; Tofte, S.J.; Hanifin, J.M. Does food allergy cause atopic dermatitis? Food challenge testing to dissociate eczematous from immediate reactions. Dermatol. Ther. 2006, 19, 97–103.

- Liacouras, C.A.; Spergel, J.M.; Ruchelli, E.; Verma, R.; Mascarenhas, M.; Semeao, E.; Flick, J.; Kelly, J.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.; Mamula, P.; et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: A 10-year experience in 381 children. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2005, 3, 1198–1206.

- Kelly, K.J. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000, 30, S28–S35.

- Markowitz, J.E.; Spergel, J.M.; Ruchelli, E.; Liacouras, C.A. Elemental diet is an effective treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adolescents. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 98, 777–782.

- Rothenberg, M.E. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (egid). J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 11–28.

- Sampson, H.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Birnbaum, A.H. Aga technical review on the evaluation of food allergy in gastrointestinal disorders. American gastroenterological association. Gastroenterology 2001, 120, 1026–1040.

- Uppal, V.; Kreiger, P.; Kutsch, E. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis and colitis: A comprehensive review. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2016, 50, 175–188.

- Cotton, C.C.; Eluri, S.; Wolf, W.A.; Dellon, E.S. Six-Food elimination diet and topical steroids are effective for eosinophilic esophagitis: A meta-regression. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2017, 62, 2408–2420.

- Steinbach, E.C.; Hernandez, M.; Dellon, E.S. Eosinophilic esophagitis and the eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases: Approach to diagnosis and management. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2018, 6, 1483–1495.

- Gonsalves, N. Eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 57, 272–285.

- Hirano, I.; Dellon, E.S.; Hamilton, J.D.; Collins, M.H.; Peterson, K.; Chehade, M.; Schoepfer, A.M.; Safroneeva, E.; Rothenberg, M.E.; Falk, G.W.; et al. Efficacy of dupilumab in a phase 2 randomized trial of adults with active eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2020, 158, 111–122.e110.

- Eigenmann, P.A.; Sicherer, S.H.; Borkowski, T.A.; Cohen, B.A.; Sampson, H.A. Prevalence of ige-mediated food allergy among children with atopic dermatitis. Pediatrics 1998, 101, E8.

- Bergmann, M.M.; Caubet, J.C.; Boguniewicz, M.; Eigenmann, P.A. Evaluation of food allergy in patients with atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 2013, 1, 22–28.

- Chung, B.Y.; Cho, S.I.; Ahn, I.S.; Lee, H.B.; Kim, H.O.; Park, C.W.; Lee, C.H. Treatment of atopic dermatitis with a low-histamine diet. Ann. Dermatol. 2011, 23, S91–S95.

- Mehta, H.; Groetch, M.; Wang, J. Growth and nutritional concerns in children with food allergy. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2013, 13, 275–279.

- Straumann, A.; Bussmann, C.; Zuber, M.; Vannini, S.; Simon, H.U.; Schoepfer, A. Eosinophilic esophagitis: Analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2008, 6, 598–600.

- Klinnert, M.D. Psychological impact of eosinophilic esophagitis on children and families. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2009, 29, 99–107.

- Spergel, J.M.; Brown-Whitehorn, T.F.; Beausoleil, J.L.; Franciosi, J.; Shuker, M.; Verma, R.; Liacouras, C.A. 14 years of eosinophilic esophagitis: Clinical features and prognosis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2009, 48, 30–36.