Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Behavioral Sciences

Sustainable Consumer Behavior, namely a new sustainable consumer model, refers to major shifts in buying and consumption habits. Nevertheless, these shifts were lagging as consumers resisted change in the comfort of old habits. This comfort was shaken up by the COVID-19 outbreak that forced us to rethink every aspect of our lives. Therefore, this crisis context seems the perfect opportunity to shift towards the sustainable consumer model.

- covid-19

- domestic consumption

- consumer behavior

- sustainability

1. Introduction

As consumption has become an exceedingly important part of our daily lives, it has come to be treated as a subject deserving scholarly inquiry. This focus, though, is relatively new. Historically, the study of sociology and other research disciplines is dominated by what has been labeled as productivist bias. Production and function were preferred overconsumption by classical thinkers such as Adam Smith and Karl Marx and, until recently, by contemporary social observers [1][2]. Beginning in the 1960s, anthropologists, economists, political scientists, and sociologists began to objectively criticize this productivist bias by explaining the role of demand and consumers in industrial culture growth, both historically and empirically. Miller et al. (1998) describe three periods of consumer research, with the first beginning in the 1960s and culminating in the late 1970s with the loss of factory employment and conventional working-class society in Western societies [3]. Researchers found that consumption entered the social sciences during the second stage of consumer research, which continued from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. Consumption was recognized as a critical component of industrialization, rather than just a byproduct of it, at that time [4]. Interestingly, one might argue that a consumerist bias arose during this second stage when consumption was often examined independently from manufacturing processes. It was particularly true for research that focused on consumer’s subjectivity and postmodern culture [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12].

This neglect of productivity began to be rectified in the early 1990s and persists today throughout the third stage of consumer research, which links consumer behavior to worker care and the environmental impact of production and consumption. The historical history of consumerism, especially in the United States, is an expanding field of study [13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21]. Efforts to incorporate ethical, social, and political issues are now focused on the public, including the belief that customers are activists and people who can exercise social and political rights in the marketplace [22][23][24][25][26].

Many researchers have recently turned their focus to the environmental effects of consumption. Paul Ehrlich, who authored the well-known books “The Population Bomb” (1968) and “Population Explosion” (1990), has shifted his focus to arguing that “consumption factor” needs to be studied rather than population [27][28]. A worldwide consumer movement has also changed Norman Myer’s focus on environmental impact, stating that we are in the middle of one of the most significant changes in the industry’s history: the rise of the developing-country population [29]. The rapid increase in the numbers of these new customers poses us with one of the most significant potential challenges: how to accomplish ever-greater resource consumption—or an alternate sort—without drastically diminishing the economic foundation on which our economies rest [29]. Sustainable use is seen as a means for bettering the quality of living [30], both materially and environmentally. Both technology advancements [31] and marketplace strategies are essential aspects of sustainable consumption through [32]: shared and guaranteed basic needs of the global community; enhancing or creating intellectual capital; and social consciousness and equable spread of resources [33]. Research has shown that sustainable consumption is related to human growth but needs additional money from personal wages, informal jobs, and natural resources [33].

The subject of consumption is the arena of many determinations in the field of critical sociology, the ground on which the consumer’s “right of preference” is readily assimilated to a veil of delusion. The dramatic increase in critique also signifies the passing of an age and the subsequent “normal transition” from that subject. Baudrillard’s essay on the “consumption society” (1970) did not mean the end of the social form he was attempting to dismantle; on the contrary, it was the beginning of a new one [34][35]. His condemnation of the impact of consumption on human liberty and social relations has been prevalent—considering his lack of motivation to leave this form of culture. On the opposite, the world of tangible products, sold or purchased, has never been so widespread (and, we may add, urgent) in our society as it is now, thanks to the apparent “virtualization” of commercial exchanges.

Consumers and end-of-chain consumers of products produced worldwide must accept additional obligations as a result of globalization. Consumerism helps to underwrite global socioeconomic, intergenerational, and ecological inequity in our world. There is no possible growth in the economy without expansion of demand fostered by the entire system, especially from customers. In modern times, it can be described as a society governed by a growth-based economy and succumbs to a market economy of growth. Humans are tempted to use things as a means to achieve a more extraordinary life and live to consume more things; it is, for that reason, that simple. The usage and consumption cannot occur if the environmental ecosystem hits its limits, as much as the oppression of scarce resources does.

Consumer behavior is described as consumers looking for, buying, using, reviewing, and disposing of, respectively, goods that meet their needs [36][37][38]. When resources are scarce, the actions of individuals involve factors that contribute to consumption and spending (time, capital, effort) [39]. It considers what/why/when/where/how often they buy it, how often they use it, how much they assess those decisions, and how they manage to dispose of it.

The study of consumer behavior started in the mid- to late-1960s. Since there was no tradition or body of scientific research to go on its own, marketing theorists often pulled in ideas from other scientific disciplines, including psychology (the individual), sociology (groups), social psychology (group influence), anthropology (society) and economics, to create a new discipline from the ground [40]. Up to this point, much of consumer behavior has been derived from economic theory, consumers seeking to make full use of their advantages (satisfactions). Later studies have shown that customers are as likely to buy impulsively and motivated not only by family and friends but also by emotions, advertisements, situations, and the feelings they are experiencing. The perspectives gained from each source work together to provide a complete image of customer behavior, taking into account both the cognitive and emotional decision-making aspects [41][42][43].

To better understand people’s basic demands while protecting the environment, a definition for these “needs” has to be given. We all should benefit from growth. Social considerations and altruism are crucial for long-term success. As the world should be available for future generations, it must be preserved and restored. On the one hand, traditional forms of production and consumption and modern ones, like sustainable economies, are contrasted with conventional economic models. On the other hand, corporate values, business ethics, and corporate governance pose the challenge of integrating environmental and social concerns into corporate strategies.

Following debates about public goods, such as physiological and psychological needs, this distinction has proved biased and even unsustainable. Some sociologists and anthropologists believe that all needs are cultural. In contrast, others claim that products are merely used as a means of material culture from which groups attempt to enforce their boundaries. According to Baudrillard, the fundamental issue with most consumer culture consumption is that it reflects a long-suppressed appetite of those who live in it [35][44][45].

However, the level of sophistication of consumption has risen over the years. Recent social trends should be included in the study of consumer preferences, including the following [46]:

-

The triumph of the demand side over the supply side, as well as the rise of the customer as a sovereign subject willing to assert control over the market. New sources of knowledge and communication, ample opportunities, and new evaluation capabilities have altered consumption behavior. All of this affects both the selection of items to be consumed and how they are used/consumed.

-

There will be new varieties of contact between consumers and firms because of free-market standards being applied within self-regulation.

-

The impact of the producer’s marketplaces requires corporate ethics, market accountability, risk assessment, and audit in production.

-

Brands play an important role in behavior because they affect family, community, education, the workplace, and everyday life and work, and they are part of a much larger scale of social networks.

-

At the same time, new alliances between groups that are mutually opposed, such as customers and unions, and forces that transcend markets, would arise within the context of globalization.

Finally, policies that target individual consumption often employ prescriptive elements (such as taxes or information) to justify consumers’ behavior. Individuals can engage in sustainable development’s social and environmental aspects, but institutional limits govern their responsibilities. As resources and processes are inseparable, behaviors can fundamentally alter our decisions and how our social class affects our thought patterns. The good news is that improvements in consumption are possible and should be welcomed.

To face the current growth demands, consumer-goods firms may need to take on a new strategy. Data-driven marketing, marketing via digital means [47], and programmatic mergers and acquisitions [48] would be significant for their goals to be achieved.

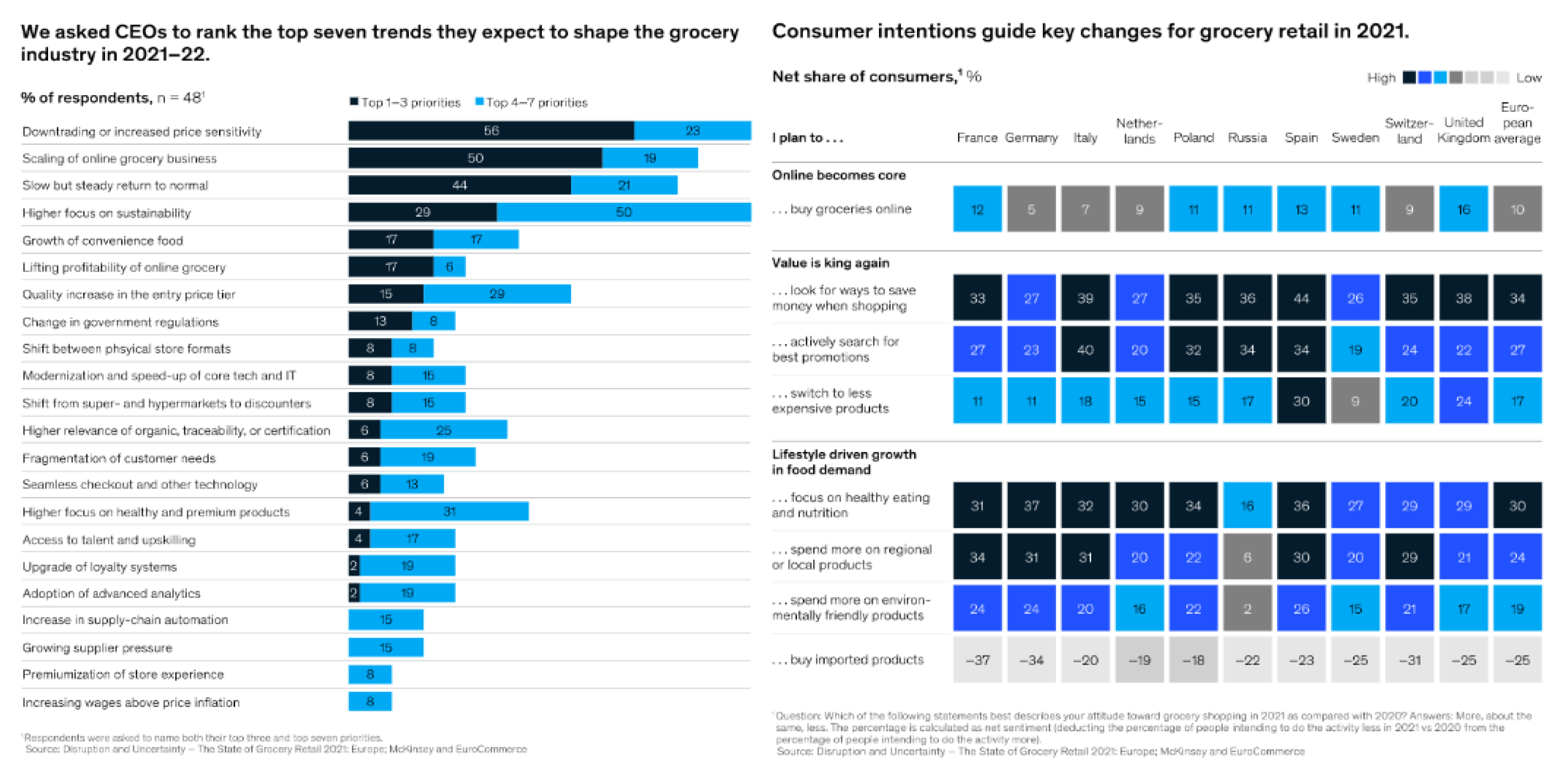

According to a McKinsey & Company report [49], based on both CEO surveys and consumer research, there were identified ten trends (Figure 1) that are believed to shape the industry over the following years (primarily driven by COVID-19).

Figure 1. Key trends shaping the industry: CEOs’ views of fundamental industry-shaping changes, and shopping intentions of consumers.

Figure 1. Key trends shaping the industry: CEOs’ views of fundamental industry-shaping changes, and shopping intentions of consumers.The COVID-19 crisis has intensified the movement toward more organic, affordable, and local goods, with no sign of abating. Across Europe, 30% of respondents intend to spend more on healthy eating and wellness in 2021 versus 2020, 24% plan to spend more on regional and local goods, and 19% plan to spend more on environmentally friendly products. Many individualized factors continue to affect these patterns, including economic conditions [50]. Consumers who have more disposable income tend to be less frugal in their spending habits and more open to health and nutrition. To a large degree, lower-income populations concentrate on what they can afford and less on what they need concerning healthier food choices.

2. Leveraging COVID-19 Outbreak for Shaping a More Sustainable Consumer Behavior

Using as a starting point consumers’ perception and take on their financial situation and their overall professional life is argued by the fact that consumers’ estimation of their future financial situation is a salient indicator of “consumer confidence” that is one predictor of consumers buying behavior. As Solomon et al. [51] show, “when people are pessimistic about their prospects and the state of the economy, they tend to cut back their spending and take on less debt.” The respondents’ estimation and perception that their financial situation is mostly worse or significantly worse than 3 months ago are consistent with the Eurostat results showing a decrease of 4.8% in 2020 in the total employment income at the EU level [52]. When estimating their future financial situation, respondents proved a pretty optimistic perspective on their future, which might result from our culture’s optimistic bias discovered by Druică et al. [53]. All these elements related to income and perception of the financial present and future situation are essential in understanding the underlying elements that influence consumer behavior and how it is exposed to changes in the COVID-19 era. These results show how uncertainty has the power to influence consumers’ dark views over their financial outcomes. Moreover, the moment this uncertainty becomes a bit more specific (or maybe, the moment consumers get used to that level of uncertainty), expectations and perception become more optimistic for the Romanian consumer.

When referring to the impact of perceptions over the financial situation, perceiving that the financial situation is currently worse than it used to be 3 months ago might also be one of the causes why respondents believed that prices have increased during the outbreak. Besides their subjective bias, respondents’ perception of price increases is supported by a report issued by Euromonitor [54] arguing that “spending on essentials such as food, non-alcoholic beverages, and housing is likely to rise mainly due to higher costs of living (especially food prices)”, a statistic also consistent with 57.7% of the respondents that said that their food consumption did not increase in terms of quantity. Despite not changing in terms of quantity, for sure, the habits that led the way while purchasing have changed. Some of the changes discovered in our research prove that consumers are making more prudent purchasing decisions while buying more and more discounted products. It confirms a study conducted by McKinsey [49] showing that 12 disruptive trends have battered the model for the consumer goods, out of which two are relevant in the current context: “conscious eating and living” and “steady rise of discounters” (and the COVID-19 impact enhanced both these trends). One-way consumer behavior seems to be moving more and more towards a sustainable model: bringing awareness in the way people spend money is ground zero in understanding which decisions serve them and which do not serve them. Respondents in this research project confirmed that their awareness level has changed in two significant directions: general awareness and ways towards more efficient resource management.

When speaking about surprising research results, we can include in this category the fact that online shopping from supermarkets or hypermarkets was rather unappealing for the Romanian consumers, as opposed to other statistics that showed different results [49][55]. One reason for such an odd result might relate to the fact that supermarket or hypermarket shopping in Romania is not a general service and is most frequent in big cities while being a rare service in smaller cities. These results offer another perspective on changing buying behavior: technology adoption for a more efficient resource usage has still a long way to expand in Romania.

Moreover, consumers’ willingness to buy from local and national producers is another primary outcome of the COVID-19 outbreak that is likely to favor the appearance of a consumer that is “increasingly aware of the impacts of their lifestyle on both the planet and the society” [52]. It also confirms Accenture’s results that discovered that 61% of consumers “are making more environmentally friendly, sustainable or ethical purchases” [55]. Even more than that, the same report shows that out of that 61% of consumers, a share of 89% is likely to continue post-crisis with these sustainable changes [55]. The respondents’ interest in buying local, together with their increased interest in fresh products, shows another window of opportunity: understanding the global supply chain’s fragility (based on their own experience during the COVID-19 outbreak), respondents turned to local products. They stuck with them also when restrictions were not so strict on the national level. Such a trend is likely to stick around given that it has become a lifestyle habit that is enforced with every day that the consumer spends under exceptional, rocky circumstances.

All in all, these results show how significant changes were a part of people’s every aspect of life, starting from their view on the level of certainty they experience in their professional life and with their financial situation, towards understating their perceptions and their consumption choices. Based on the fact that most May results were consistent with the December results, these changes seem to stay here. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fact that there were a few changes between May and December that might already be signaling that the window of opportunity is closing on the long-lasting consumer behavior changes.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13115762

References

- Parsons, E.; Maclaran, P. Contemporary Issues in Marketing and Consumer Behaviour; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; ISBN 1-136-44155-7.

- Ritzer, G.; Goodman, D.; Wiedenhoft, W. Theories of consumption. In Handbook of Social Theory; Sage: London, UK, 2001.

- Miller, D.; Jackson, P.; Rowlands, M.; Thrift, N.; Holbrook, B. Shopping, Place, and Identity; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1998.

- Slater, D. Consumer Culture and Modernity; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1997.

- Singh, P.R. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism. Postmod. Open 2011, 2, 55–88.

- Featherstone, M. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism; Sage: London, UK, 2007.

- McCracken, G.D. Culture and Consumption II: Markets, Meaning, and Brand Management; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2005; Volume 2.

- Boden, S.; Williams, S.J. Consumption and Emotion: The Romantic Ethic Revisited. Sociology 2002, 36, 493–512.

- Featherstone, M. Perspectives on Consumer Culture. Sociology 1990, 24, 5–22.

- McCracken, G.D. Culture and Consumption: New Approaches to the Symbolic Character of Consumer Goods and Activities; Indiana University Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 1990; Volume 1.

- McCracken, G. Culture and Consumption: A Theoretical Account of the Structure and Movement of the Cultural Meaning of Consumer Goods. J. Consum. Res. 1986, 13, 71–84.

- Campbell, C. The Romantic Ethic and the Spirit of Modern Consumerism; Springer: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Deutsch, T. Building a Housewife’s Paradise: Gender, Politics, and American Grocery Stores in the Twentieth Century; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-8078-3327-8.

- Shah, D.V.; McLeod, D.M.; Friedland, L.; Nelson, M.R. The Politics of Consumption/the Consumption of Politics; Sage Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2007.

- McGovern, C. Sold American: Consumption and Citizenship, 1890–1945; University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2006; ISBN 978-0-8078-3033-8.

- Cohen, L. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America. J. Consum. Res. 2004, 31, 236–239.

- Ritzer, G. A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America; JSTOR: New York, NY, USA, 2004.

- Kroen, S. A Political History of the Consumer. Hist. J. 2004, 47, 709–736.

- Cross, G. An All-Consuming Century: Why Commercialism Won in Modern America; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-231-50253-5.

- Glickman, L.B. A Living Wage: American Workers and the Making of Consumer Society; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1999; ISBN 978-0-8014-8614-2.

- Voss, K.; Voss, P. of S.K. The Making of American Exceptionalism: The Knights of Labor and Class Formation in the Nineteenth Century; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-8014-2882-1.

- Ekström, K.M.; Brembeck, H. Elusive Consumption; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-00-018282-8.

- Hyman, L.; Tohill, J. Shopping for Change: Consumer Activism and the Possibilities of Purchasing Power; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 978-1-5017-1263-0.

- Hilton, M. Prosperity for All: Consumer Activism in an Era of Globalization; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-8014-6163-7.

- Glickman, L.B. Buying Power: A History of Consumer Activism in America; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0-226-29866-5.

- Breen, T.H. The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-518131-9.

- Ehrlich, P.; Ehrlich, A. The Population Explosion; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- Ehrlich, P. The Population Bomb; Sierra Club/Ballantine Books: New York, NY, USA, 1968.

- Myers, N.; Kent, J. New Consumers: The Influence of Affluence on the Environment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 4963–4968.

- Voicu-Dorobanțu, R. European Regions and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in the Context of the New Sustainable Development Goals. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2016, 2016, 1–16.

- Onete, B.; Constantinescu, M.; Filip, A. Main Issues Regarding the Relationship between Cognitive Maps and Internet Consumer Behavior—A Knowledge Based Approach. Amfiteatru Econ. J. 2007, 9, 115–120.

- Murphy, W.W. Consumer Culture and Society; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4833-5814-7.

- Programme, U.N.D. Human Development Report 1998; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-0-19-512459-0.

- Galbraith, J.K. The Affluent Society; Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: Boston, MA, USA, 1998.

- Baudrillard, J. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures; SAGE: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4739-9454-6.

- Stephens, D.L. Essentials of Consumer Behavior; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016; ISBN 1-317-64885-4.

- Ling, P.; D’Alessandro, S.; Winzar, H. Consumer Behaviour in Action; Oxford University Press: Victoria, Hong Kong, 2015.

- Schiffman, L.G.; Kanuk, L.; Hansen, H. Consumer Behaviour—A European Outlook; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-0-273-72425-4.

- Foxall, G.R. Consumer Behaviour: A Practical Guide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014.

- Graves, P. Consumerology: The Truth about Consumers and the Psychology of Shopping; Hachette UK: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-1-85788-923-9.

- Mothersbaugh, D.L.; Hawkins, D.I.; Kleiser, S.B. Consumer Behavior: Building Marketing Strategy; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2019; ISBN 978-1-260-10004-4.

- Smith, A. Consumer Behaviour and Analytics: Data Driven Decision Making; Routledge: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- Noel, H. Basics Marketing 01: Consumer Behaviour; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-350-03466-2.

- Baudrillard, J. The System of Objects; Verso: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-84467-053-6.

- Baudrillard, J. The System of Objects. Art Mon. 1988, 115, 5.

- Zaccaï, E. Sustainable Consumption, Ecology and Fair Trade; Routledge: Oxon, UK, 2007.

- Kotler, P.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 4.0: Moving from Traditional to Digital; John Wiley & Sons: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-1-119-34114-7.

- Kotler, P.; Kartajaya, H.; Setiawan, I. Marketing 5.0: Technology for Humanity; John Wiley & Sons: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2021; ISBN 1-119-66854-9.

- Kopka, U.; Little, E.; Moulton, J.; Schmutzler, R.; Simon, P. What Got Us Here Won’t Get Us There: A New Model for the Consumer Goods Industry; McKinsey: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- Radulescu, C.V.; Ladaru, G.-R.; Burlacu, S.; Constantin, F.; Ioanăș, C.; Petre, I.L. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the Romanian Labor Market. Sustainability 2021, 13, 271.

- Solomon, M.R.; Bamossy, G.; Askegaard, S.; Hogg, M.K. Consumer Behaviour: A European Perspective; Pearson: Edinburgh Gate, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-292-11672-3.

- Euromonitor. From Sustainability to Purpose: New Values Driving Purpose-Led Innovation; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2020.

- Druică, E.; Musso, F.; Ianole-Călin, R. Optimism Bias during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Empirical Evidence from Romania and Italy. Games 2020, 11, 39.

- Euromonitor. Emerging Markets’ Middle Class Consumers in the Coronavirus Era; Euromonitor International: London, UK, 2020.

- Accenture COVID-19: Retail Consumer Habits Shift Long-Term|Accenture. Available online: (accessed on 1 April 2021).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!