Melanins are ubiquitous complex polymers that are commonly known in humans to cause pigmentation of our skin. Melanins are also present in bacteria, fungi, and helminths.

- melanin

- fungus

- yeast

- immune response

1. Introduction

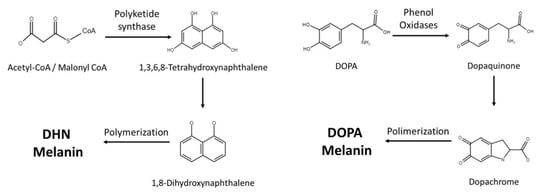

2. Melanin Synthesis

|

Species |

Isolate Environment |

Melanin Types |

|---|---|---|

|

Aspergillus fumigatus |

Clinical |

DHN and pyo-melanin |

|

Aspergillus niger |

Industrial fermentation |

DHN and L-DOPA |

|

Blastomyces dermatitidis |

Clinical |

DHN |

|

Candida Albicans |

Clinical |

L-DOPA |

|

Cryptococcus neoformans |

Clinical |

L-DOPA |

|

Histoplasma capsulatum |

Clinical |

DHN and L-DOPA |

|

Paracoccidioides brasiliensis |

Clinical |

DHN and L-DOPA |

|

Fonsecaea monophora |

Clinical |

DHN and L-DOPA |

|

Fonsecaea pedrosoi |

Clinical |

DHN |

|

Sporothrix schenckii |

Clinical |

DHN |

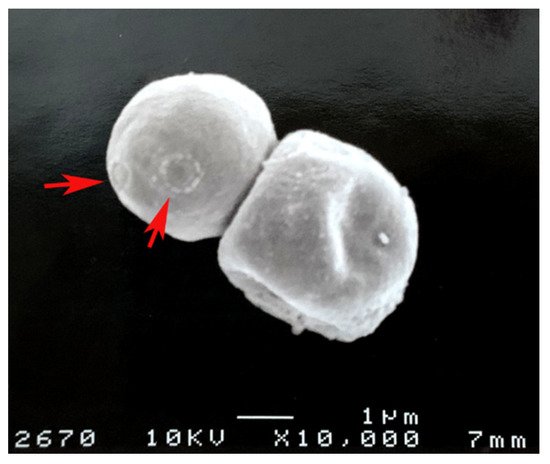

3. Cryptococcus neoformans

4. Aspergillus fumigatus

5. Other Melanotic Fungi and Their Interactions with the Immune System

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jof7040264

References

- Suwannarach, N.; Kumla, J.; Watanabe, B.; Matsui, K.; Lumyong, S. Characterization of melanin and optimal conditions for pigment production by an endophytic fungus, Spissiomyces endophytica SDBR-CMU319. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222187.

- Riley, P.A. Melanin. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1997, 29, 1235–1239.

- Eisen, T.G. The control of gene expression in melanocytes and melanomas. Melanoma Res. 1996, 6, 277–284.

- Sánchez-Ferrer, Á.; Neptuno Rodríguez-López, J.; García-Cánovas, F.; García-Carmona, F. Tyrosinase: A comprehensive review of its mechanism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Protein Struct. Mol. Enzymol. 1995, 1247, 1–11.

- Wheeler, M.H.; Bell, A.A. Melanins and their importance in pathogenic fungi. In Current Topics in Medical Mycology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1988; pp. 338–387.

- Staunton, J.; Weissman, K.J. Polyketide biosynthesis: A millennium review. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2001, 18, 380–416.

- Butler, M.; Day, A. Fungal melanins: A review. J. Can. J. Microbiol. 1998, 44, 1115–1136.

- Langfelder, K.; Streibel, M.; Jahn, B.; Haase, G.; Brakhage, A.A. Biosynthesis of fungal melanins and their importance for human pathogenic fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2003, 38, 143–158.

- Katz, L. Manipulation of Modular Polyketide Synthases. Chem. Rev. 1997, 97, 2557–2576.

- Huffman, J.; Gerber, R.; Du, L. Recent advancements in the biosynthetic mechanisms for polyketide-derived mycotoxins. Biopolymers 2010, 93, 764–776.

- Hopwood, D.A. Complex enzymes in microbial natural product biosynthesis, part B: Polyketides, aminocoumarins and carbohydrates. Preface. Methods Enzymol. 2009, 459, xvii–xix.

- Eisenman, H.C.; Greer, E.M.; McGrail, C.W. The role of melanins in melanotic fungi for pathogenesis and environmental survival. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2020, 104, 4247–4257.

- Morris-Jones, R.; Youngchim, S.; Gomez, B.L.; Aisen, P.; Hay, R.J.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Casadevall, A.; Hamilton, A.J. Synthesis of Melanin-Like Pigments by Sporothrix schenckiix In Vitro and during Mammalian Infection. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 4026–4033.

- Walker, C.A.; Gómez, B.L.; Mora-Montes, H.M.; Mackenzie, K.S.; Munro, C.A.; Brown, A.J.P.; Gow, N.A.R.; Kibbler, C.C.; Odds, F.C. Melanin externalization in Candida albicans depends on cell wall chitin structures. Eukaryot Cell 2010, 9, 1329–1342.

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Van Duin, D.; Mandal, P.; Aisen, P.; Legendre, A.M.; Casadevall, A. Blastomyces dermatitidis produces melanin in vitro and during infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2004, 239, 187–193.

- McClelland, E.E.; Bernhardt, P.; Casadevall, A. Estimating the relative contributions of virulence factors for pathogenic microbes. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 1500–1504.

- Chatterjee, S.; Prados-Rosales, R.; Frases, S.; Itin, B.; Casadevall, A.; Stark, R.E. Using solid-state NMR to monitor the molecular consequences of Cryptococcus neoformans melanization with different catecholamine precursors. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 6080–6088.

- Almeida-Paes, R.; Frases, S.; Fialho Monteiro, P.C.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Zancope-Oliveira, R.M.; Nosanchuk, J.D. Growth conditions influence melanization of Brazilian clinical Sporothrix schenckii isolates. Microbes Infect. 2009, 11, 554–562.

- Eisenman, H.C.; Casadevall, A. Synthesis and assembly of fungal melanin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 931–940.

- Rosas, A.L.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Feldmesser, M.; Cox, G.M.; McDade, H.C.; Casadevall, A. Synthesis of polymerized melanin by Cryptococcus neoformans in infected rodents. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 2845–2853.

- Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Polacheck, I.; Popkin, T.J. Melanin-lacking mutants of Cryptococcus neoformans and their virulence for mice. J. Bacteriol. 1982, 150, 1414–1421.

- Rhodes, J.C.; Polacheck, I.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Phenoloxidase activity and virulence in isogenic strains of Cryptococcus neoformans. Infect. Immun. 1982, 36, 1175–1184.

- Williamson, P.R. Biochemical and molecular characterization of the diphenol oxidase of Cryptococcus neoformans: Identification as a laccase. J. Bacteriol. 1994, 176, 656–664.

- Salas, S.D.; Bennett, J.E.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Perfect, J.R.; Williamson, P.R. Effect of the laccase gene CNLAC1, on virulence of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Exp. Med. 1996, 184, 377–386.

- Pukkila-Worley, R.; Gerrald, Q.D.; Kraus, P.R.; Boily, M.-J.; Davis, M.J.; Giles, S.S.; Cox, G.M.; Heitman, J.; Alspaugh, J.A. Transcriptional network of multiple capsule and melanin genes governed by the Cryptococcus neoformans cyclic AMP cascade. Eukaryot Cell 2005, 4, 190–201.

- Tsai, H.F.; Chang, Y.C.; Washburn, R.G.; Wheeler, M.H.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: Its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 1998, 180, 3031–3038.

- Tsai, H.F.; Wheeler, M.H.; Chang, Y.C.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. A developmentally regulated gene cluster involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis in Aspergillus fumigatus. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 6469–6477.

- Abad, A.; Fernández-Molina, J.V.; Bikandi, J.; Ramírez, A.; Margareto, J.; Sendino, J.; Hernando, F.L.; Pontón, J.; Garaizar, J.; Rementeria, A. What makes Aspergillus fumigatus a successful pathogen? Genes and molecules involved in invasive aspergillosis. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2010, 27, 155–182.

- Jahn, B.; Boukhallouk, F.; Lotz, J.; Langfelder, K.; Wanner, G.; Brakhage, A.A. Interaction of human phagocytes with pigmentless Aspergillus conidia. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 3736–3739.

- Chai, L.Y.; Netea, M.G.; Sugui, J.; Vonk, A.G.; Van de Sande, W.W.; Warris, A.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; Kullberg, B.J. Aspergillus fumigatus conidial melanin modulates host cytokine response. Immunobiology 2010, 215, 915–920.

- Luther, K.; Torosantucci, A.; Brakhage, A.A.; Heesemann, J.; Ebel, F. Phagocytosis of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by murine macrophages involves recognition by the dectin-1 beta-glucan receptor and Toll-like receptor 2. Cell. Microbiol. 2007, 9, 368–381.

- Jahn, B.; Langfelder, K.; Schneider, U.; Schindel, C.; Brakhage, A.A. PKSP-dependent reduction of phagolysosome fusion and intracellular kill of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia by human monocyte-derived macrophages. Cell. Microbiol. 2002, 4, 793–803.

- Thywißen, A.; Heinekamp, T.; Dahse, H.M.; Schmaler-Ripcke, J.; Nietzsche, S.; Zipfel, P.F.; Brakhage, A.A. Conidial Dihydroxynaphthalene Melanin of the Human Pathogenic Fungus Aspergillus fumigatus Interferes with the Host Endocytosis Pathway. Front. Microbiol. 2011, 2, 96.

- Sanjuan, M.A.; Dillon, C.P.; Tait, S.W.; Moshiach, S.; Dorsey, F.; Connell, S.; Komatsu, M.; Tanaka, K.; Cleveland, J.L.; Withoff, S.; et al. Toll-like receptor signalling in macrophages links the autophagy pathway to phagocytosis. Nature 2007, 450, 1253–1257.

- Kyrmizi, I.; Ferreira, H.; Carvalho, A.; Figueroa, J.A.L.; Zarmpas, P.; Cunha, C.; Akoumianaki, T.; Stylianou, K.; Deepe, G.S.; Samonis, G.; et al. Calcium sequestration by fungal melanin inhibits calcium–calmodulin signalling to prevent LC3-associated phagocytosis. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 791–803.

- Martinez, J.; Malireddi, R.S.; Lu, Q.; Cunha, L.D.; Pelletier, S.; Gingras, S.; Orchard, R.; Guan, J.-L.; Tan, H.; Peng, J. Molecular characterization of LC3-associated phagocytosis reveals distinct roles for Rubicon, NOX2 and autophagy proteins. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 893–906.

- Yang, C.-S.; Lee, J.-S.; Rodgers, M.; Min, C.-K.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, K.-H.; Kim, C.-J.; Oh, B.; Zandi, E. Autophagy protein Rubicon mediates phagocytic NADPH oxidase activation in response to microbial infection or TLR stimulation. Cell Host Microbe 2012, 11, 264–276.

- Akoumianaki, T.; Kyrmizi, I.; Valsecchi, I.; Gresnigt, M.S.; Samonis, G.; Drakos, E.; Boumpas, D.; Muszkieta, L.; Prevost, M.-C.; Kontoyiannis, D.P. Aspergillus cell wall melanin blocks LC3-associated phagocytosis to promote pathogenicity. Cell Host Microbe 2016, 19, 79–90.

- Bayry, J.; Beaussart, A.; Dufrêne, Y.F.; Sharma, M.; Bansal, K.; Kniemeyer, O.; Aimanianda, V.; Brakhage, A.A.; Kaveri, S.V.; Kwon-Chung, K.J.; et al. Surface structure characterization of Aspergillus fumigatus conidia mutated in the melanin synthesis pathway and their human cellular immune response. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 3141–3153.

- Stappers, M.H.T.; Clark, A.E.; Aimanianda, V.; Bidula, S.; Reid, D.M.; Asamaphan, P.; Hardison, S.E.; Dambuza, I.M.; Valsecchi, I.; Kerscher, B.; et al. Recognition of DHN-melanin by a C-type lectin receptor is required for immunity to Aspergillus. Nature 2018, 555, 382–386.

- Gonçalves, S.M.; Duarte-Oliveira, C.; Campos, C.F.; Aimanianda, V.; Ter Horst, R.; Leite, L.; Mercier, T.; Pereira, P.; Fernández-García, M.; Antunes, D.; et al. Phagosomal removal of fungal melanin reprograms macrophage metabolism to promote antifungal immunity. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2282.

- Majumder, P.K.; Febbo, P.G.; Bikoff, R.; Berger, R.; Xue, Q.; McMahon, L.M.; Manola, J.; Brugarolas, J.; McDonnell, T.J.; Golub, T.R.; et al. mTOR inhibition reverses Akt-dependent prostate intraepithelial neoplasia through regulation of apoptotic and HIF-1-dependent pathways. Nat. Med. 2004, 10, 594–601.

- Sturtevant, J.; Latgé, J.P. Participation of complement in the phagocytosis of the conidia of Aspergillus fumigatus by human polymorphonuclear cells. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 166, 580–586.

- Behnsen, J.; Hartmann, A.; Schmaler, J.; Gehrke, A.; Brakhage, A.A.; Zipfel, P.F. The Opportunistic Human Pathogenic Fungus Aspergillus fumigatus Evades the Host Complement System. J. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 820–827.

- Tsai, H.F.; Washburn, R.G.; Chang, Y.C.; Kwon-Chung, K.J. Aspergillus fumigatus arp1 modulates conidial pigmentation and complement deposition. Mol. Microbiol. 1997, 26, 175–183.

- Langfelder, K.; Jahn, B.; Gehringer, H.; Schmidt, A.; Wanner, G.; Brakhage, A.A. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 1998, 187, 79–89.

- Rosas, A.L.; MacGill, R.S.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Kozel, T.R.; Casadevall, A. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by fungal melanins. Clin. Diagn Lab. Immunol. 2002, 9, 144–148.

- Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Xi, L.; Huang, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, X.; Lu, S.; Sun, J. Melanin in a meristematic mutant of Fonsecaea monophora inhibits the production of nitric oxide and Th1 cytokines of murine macrophages. Mycopathologia 2013, 175, 515–522.

- Shi, M.; Sun, J.; Lu, S.; Qin, J.; Xi, L.; Zhang, J. Transcriptional profiling of macrophages infected with Fonsecaea monophora. Mycoses 2019, 62, 374–383.

- Pinto, L.; Granja, L.F.Z.; Almeida, M.A.d.; Alviano, D.S.; Silva, M.H.d.; Ejzemberg, R.; Rozental, S.; Alviano, C.S. Melanin particles isolated from the fungus Fonsecaea pedrosoi activates the human complement system. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113.

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Gómez, B.L.; Youngchim, S.; Díez, S.; Aisen, P.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Restrepo, A.; Casadevall, A.; Hamilton, A.J. Histoplasma capsulatum synthesizes melanin-like pigments in vitro and during mammalian infection. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 5124–5131.

- Gómez, B.L.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Díez, S.; Youngchim, S.; Aisen, P.; Cano, L.E.; Restrepo, A.; Casadevall, A.; Hamilton, A.J. Detection of Melanin-Like Pigments in the Dimorphic Fungal Pathogen Paracoccidioides brasiliensis In Vitro and during Infection. J. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 5760–5767.

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Yu, J.-J.; Hung, C.-Y.; Casadevall, A.; Cole, G.T. Coccidioides posadasii produces melanin in vitro and during infection. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2007, 44, 517–520.

- Youngchim, S.; Hay, R.J.; Hamilton, A.J. Melanization of Penicillium marneffei in vitro and in vivo. Microbiology 2005, 151, 291–299.

- Uran, M.E.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Restrepo, A.; Hamilton, A.J.; Gomez, B.L.; Cano, L.E. Detection of antibodies against Paracoccidioides brasiliensis melanin in in vitro and in vivo studies during infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18, 1680–1688.

- Emidio, E.C.P.; Uran, M.E.; Silva, L.B.R.; Dias, L.S.; Doprado, M.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Taborda, C.P. Melanin as a Virulence Factor in Different Species of Genus Paracoccidioides. J. Fungi. 2020, 6, 291.

- Silva, M.B.; Thomaz, L.; Marques, A.F.; Svidzinski, A.E.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Casadevall, A.; Travassos, L.R.; Taborda, C.P. Resistance of melanized yeast cells of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis to antimicrobial oxidants and inhibition of phagocytosis using carbohydrates and monoclonal antibody to CD18. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2009, 104, 644–648.

- Almeida-Paes, R.; Almeida, M.A.; Baeza, L.C.; Marmello, L.A.M.; Trugilho, M.R.O.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Soares, C.M.A.; Valente, R.H.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Beyond Melanin: Proteomics Reveals Virulence-Related Proteins in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis and Paracoccidioides lutzii Yeast Cells Grown in the Presence of L-Dihydroxyphenylalanine. J. Fungi. 2020, 6, 328.

- Tam, E.W.; Tsang, C.C.; Lau, S.K.; Woo, P.C. Polyketides, toxins and pigments in Penicillium marneffei. Toxins 2015, 7, 4421–4436.

- Sapmak, A.; Kaewmalakul, J.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Vanittanakom, N.; Andrianopoulos, A.; Pruksaphon, K.; Youngchim, S. Talaromyces marneffei laccase modifies THP-1 macrophage responses. Virulence 2016, 7, 702–717.

- Kaewmalakul, J.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Vanittanakom, N.; Youngchim, S. Melanization and morphological effects on antifungal susceptibility of Penicillium marneffei. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2014, 106, 1011–1020.

- Boyce, K.J.; McLauchlan, A.; Schreider, L.; Andrianopoulos, A. Intracellular growth is dependent on tyrosine catabolism in the dimorphic fungal pathogen Penicillium marneffei. PLoS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1004790.

- Almeida-Paes, R.; Frases, S.; Araújo Gde, S.; De Oliveira, M.M.; Gerfen, G.J.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Biosynthesis and functions of a melanoid pigment produced by species of the Sporothrix complex in the presence of L-tyrosine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 8623–8630.

- Cruz, I.L.R.; Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.G.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M.; Almeida-Paes, R. Evaluation of melanin production by Sporothrix luriei. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2018, 113, 68–70.

- Song, Y.; Yao, L.; Zhen, Y.; Cui, Y.; Zhong, S.; Liu, Y.; Li, S. Sporothrix globosa melanin inhibits antigen presentation by macrophages and enhances deep organ dissemination. Braz J. Microbiol. 2020.

- Almeida-Paes, R.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Oliveira, M.M.; Gutierrez-Galhardo, M.C.; Nosanchuk, J.D.; Zancope-Oliveira, R.M. Phenotypic characteristics associated with virulence of clinical isolates from the Sporothrix complex. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 212308.

- Madrid, I.M.; Xavier, M.O.; Mattei, A.S.; Fernandes, C.G.; Guim, T.N.; Santin, R.; Schuch, L.F.; Nobre Mde, O.; Araújo Meireles, M.C. Role of melanin in the pathogenesis of cutaneous sporotrichosis. Microbes Infect. 2010, 12, 162–165.

- Mario, D.A.; Santos, R.C.; Denardi, L.B.; Vaucher Rde, A.; Santurio, J.M.; Alves, S.H. Interference of melanin in the susceptibility profile of Sporothrix species to amphotericin B. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2016, 33, 21–25.

- Almeida-Paes, R.; Figueiredo-Carvalho, M.H.; Brito-Santos, F.; Almeida-Silva, F.; Oliveira, M.M.; Zancopé-Oliveira, R.M. Melanins Protect Sporothrix brasiliensis and Sporothrix schenckii from the Antifungal Effects of Terbinafine. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0152796.

- Soliman, S.S.M.; Hamdy, R.; Elseginy, S.A.; Gebremariam, T.; Hamoda, A.M.; Madkour, M.; Venkatachalam, T.; Ershaid, M.N.; Mohammad, M.G.; Chamilos, G.; et al. Selective inhibition of Rhizopus eumelanin biosynthesis by novel natural product scaffold-based designs caused significant inhibition of fungal pathogenesis. Biochem. J. 2020, 477, 2489–2507.