Until very recently there were no well-characterized molecular determinants of prognosis that could be used in the clinic to predict the survival of patients with PV [

7], with the ELN score only considering patient age and history of thrombosis [

21]. However, the recently proposed Mutation-enhanced International Prognostic Scoring System (MIPSS-PV) includes the mutation

SRSF2 due to its association with worse overall survival () [

130] to classify patients into low-risk (score of 0–1), intermediate-risk (score of 2–3) or high-risk (score ≥ 4) groups.

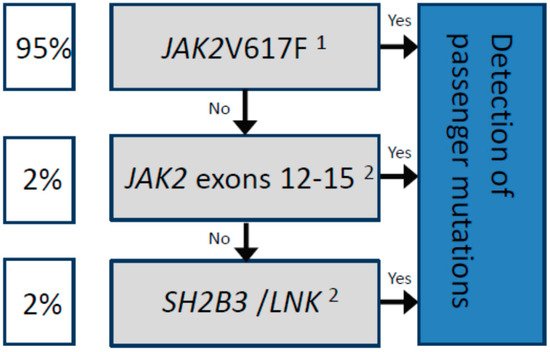

2.1. JAK2V617F Allelic Burden

Although quantification of the

JAK2V617F allelic burden is not obligatory for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with PV according to the WHO criteria [

1,

2], patients homozygous for

JAK2V617F were shown to be more symptomatic than patients who were heterozygous. Specifically, a positive correlation was described between a high allelic frequency of mutated

JAK2 and clinical presentation including pruritus [

131,

132,

133], myelopoiesis [

11,

132], splenomegaly [

11,

131,

132,

134,

135], and a negative correlation with the platelet count [

11,

132,

135,

136].

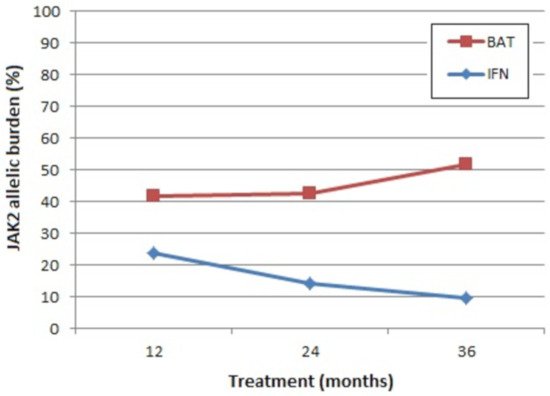

Moreover, determination of the

JAK2V617F VAF at diagnosis can provide important prognostic information. For example, in PV, a higher mutant allele burden has been associated with an increased incidence of progression to SMF [

11,

83,

131,

137].

Both of these observations are suggestive of a “dosage” effect (reviewed in [

98]), where a high

JAK2V617F burden results in a stronger activation of JAK2/STAT (and possibly other) signalling pathways, leading to the stronger activation of downstream genes [

138], and thus a more aggressive phenotype. In support of this hypothesis, the expression level of several JAK2 target genes—such as

PRV1 [

138] and

NFE2 [

139]—was shown to be dose dependent for the mutant allele burden.

A high

JAK2V617F allele burden in patients with PV has also been associated with a risk of thrombotic events [

140,

141,

142]. A study of 1306 patients with MPN including 397 patients with PV, observed an incidence of thrombosis at a diagnosis of 21% for homozygous and 15% for heterozygous

JAK2V617F [

142], with

JAK2V617F homozygosity at diagnosis identified as an independent risk factor for major vascular events in a multivariate analysis [

141]. A second study reported a 7.1-fold increased risk of major vascular events for patients with a mutant allele of 75% and above compared to less than 25% VAF during follow-up [

130]. However, one study associated a significantly increased risk of venous thromboembolism with a much lower mutant allele burden, of just 20% or more [

131]. Despite the differences in the VAF threshold reported to have a negative effect on thrombotic risk, it is clear that patients with a higher

JAK2 mutant burden are at risk of both vascular events and fibrotic transformation.

Nevertheless, one study’s findings contradict the prognostic impact of the

JAK2V617F allelic burden in patients with PV. Gene expression profiling of CD34+ cells isolated from 19 patients with PV led to the identification of a group of patients with a more aggressive disease—with higher rates of blastic transformation and worse overall survival—and a group with a less aggressive form despite similar

JAK2V617F allele frequencies in both groups. Patients in the group with more aggressive PV showed differential expression of the NOTCH and SHH pathways as well as inflammatory cytokines and histone genes [

143]. Interestingly, this study also revealed gender-specific differences in the expression profile in that men with PV had significantly more differentially regulated genes than women with PV.

2.2. Cytogenetics

Cytogenetic abnormalities are detected in approximately 10–20% of PV patients at diagnosis, with some of the most common alterations including gain of chromosomes 8 and 9, and deletion of (1p), (13q) and (20q) [

144,

145,

146].

Although some studies have not shown a prognostic difference based on cytogenetic characteristics [

146], several groups have reported, as association between a higher risk of fibrotic progression and the presence of chromosome 12 abnormalities [

147], the gain of (1q) [

148], and an abnormal karyotype. Moreover, the majority of investigations, including one by the International Working Group for Neoplasms Research and Treatment (IWG-MRT), have reported an association between an abnormal karyotype and transformation to myelodysplastic syndrome or AML [

146,

148,

149,

150] and poorer overall survival [

145,

148,

150].

Interestingly, a retrospective study of 422 PV patients with cytogenetic information available at diagnosis observed dynamic changes associated with progression to AML, including an increased frequency of abnormal karyotype, increasing from 20% to 90% in the blast phase, as well as a different distribution of cytogenetic abnormalities [

149]. For example, complex karyotype as well as deletion of (5q)/chromosome 5, 7q/chromosome 7, and (17p)/chromosome 17/i(17q) were more common in the blast phase, whereas the gain of chromosomes 8 and 9 were more common in the chronic phase of the disease. Using this information, the authors stratified patients into low (normal karyotype; +8, +9; or presence of one other alteration), intermediate (del(20q), +(1q) or presence of two other alterations) and high-risk (complex karyotype) groups according to their cytogenetics at diagnosis [

148].

2.3. Thrombosis

The

BCR-ABL1-negative MPNs PV, ET and PMF are associated with a high frequency of haemorrhages and thrombosis, including myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and thrombo- and pulmonary embolisms. Notably, vascular events are the major cause of morbimortality among patients with PV, with the incidence of events estimated between 6% and 17% over three years [

151,

152].

Thrombotic risk prediction tools have been developed for each

BCR-ABL1-negative MPN subtype. However, thrombotic events are frequent among patients with PV, even among those classified as low-risk according to the current ELN recommendations [

21,

153], as well as patients who receive cytoreductive or anti-aggregant treatment [

154].

Several common thrombophilia markers are associated with an increased risk of developing vascular events in patients with PV (reviewed in [

155]), including high levels of C-reactive protein in blood serum and SNVs in the factor V-Leiden (

F5) gene [

156,

157,

158]. Higher factor VIII levels, a known risk factor for venous thrombosis and coronary artery disease [

159], were identified in PV patients compared to healthy subjects, with levels of 141 versus 98 IU/dL, respectively [

160]. The PV patients were also found to have significantly higher VWF antigen and activity which, by multivariate analysis, was predicted for by

JAK2V617F allelic burden. Nevertheless, the ELN does not currently recommend thrombophilia testing as part of routine clinical practice in PV or MPN patients [

21,

153].

Other prognostic biomarkers reported for PV include an abnormal karyotype, identified as a risk factor for venous thrombosis [

145], and leucocytosis, a risk factor for arterial thrombosis, although its impact on venous thrombosis remains inconclusive [

161,

162].

The International Prognostic Score of thrombosis in World Health Organization-essential thrombocythemia (IPSET-thrombosis) was the first prognostic algorithm to incorporate the

JAK2V617F mutation to better predict the risk of thrombosis among ET patients [

163], although the influence of

JAK2V617F in PV patients as well as the clinical significance of the allelic burden on thrombotic risk remain to be determined. Some studies have found that a higher

JAK2V617F allelic burden was associated with increased risk of thrombosis in PV and ET [

164]. For example,

JAK2V617F allele burden cut-offs for PV > 25.7% and > 90.4% were established for arterial thrombosis and for venous thrombosis, respectively [

165].

Moreover, elevated levels of the inflammatory biomarker C-reactive protein in peripheral blood were associated with the PV phenotype (vs. essential thrombocythemia), older age, cardiovascular risk factors and a

JAK2V617F allele burden over 50% [

59,

166], further supporting suggestions of a possible link between inflammation and atherosclerosis [

58,

59,

60]. A seminal study from 2017 identified an association between mutations in the DTA and

JAK2 genes and coronary disease [

119]. Mechanistically, mutations to DTA genes are suggested to alter methylation patterns and thus cause an increased transcription of pro-inflammatory genes triggering atherosclerosis [

119,

167,

168]. To support this theory, Fuster and colleagues studied the effect of the expansion of TET2-deficient cells in atherosclerosis-prone, low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice and observed that the partial reconstitution of the bone marrow with TET2-deficient cells was sufficient to generate clonal expansion, which was also associated with a marked increase in the size of atheromatous plaques and the increased secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β [

167].

In accordance with these results, Jaiswal et al. found that individuals with clonal hematopoiesis had a 1.9-fold higher risk of developing coronary disease and a 4-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction, rising to 12.1-fold in individuals with the

JAK2V617F mutation [

119]. In support of the link between constitutive JAK2 activation and increased risk of vascular events, the rs3184504 SNP in the

SH2B3 (

LNK) gene was also associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease [

169]. This variant, encoding the TT genotype (R262W), caused an increased platelet count, leukocytosis and hypertension. At the molecular level,

SH2B3 mutation increased megakaryopoiesis via the upregulation of AKT signalling, shown to be specifically upregulated in platelets and to promote prothrombotic and proatherogenic aggregates [

170]. Specifically, our group recently showed that DTA mutations were associated with increased thrombotic risk in patients with PV, with a specific interaction identified for pathogenic

TET2 mutations [

108].

Activated leukocytes (including neutrophils and monocytes) appear to play an important role in the development of platelet aggregates, markers of a prothrombotic state. In addition, there are reports that leuko-platelet aggregations directly correlate with platelet and leukocyte counts [

171,

172], adding weight to leukocytosis as a thrombotic risk factor. Interestingly, and as previously mentioned, the expression of

CD177 (

PRV-1), a GPI-linked cell surface glycoprotein with a role in neutrophil activation, was increased in PV patients, and to a lesser extent in ET and PMF patients [

64,

65]. Indeed, higher

CD177 expression was associated with an increased risk of thrombotic and bleeding complications due to increased circulating neutrophils [

173,

174]. For a complete and recent review on the role of neutrophils in thrombosis, we refer readers to the article by Ferrer-Marín and colleagues published in this special edition [

175]. It is clear that we need to further elucidate the molecular mechanisms of leukocyte–platelet interactions in order to design better prophylactic treatment plans for the prevention of thrombotic complications in patients with PV.

2.4. Molecular Indicators of Transformation

Progression to fibrotic disease (post-PV MF) or blastic disease, both associated with dismal survival rates, is estimated to occur in 10% and 15% of PV patients, respectively [

3]. Molecular indicators of fibrotic progression from PV are not well characterized. Some evidence exists suggesting an association between chromosome 12 abnormalities and an increased risk of developing post-PV MF [

176]. Evidence also exists to support a significantly higher

JAK2V617F allelic frequency [

11,

83,

131,

137,

176] or a progressive increase [

177] in patients who transform to SMF. Unlike in PMF, the presence of additional high-risk mutations (

ASXL1, EZH2, IDH1, IDH2 or

SRSF2, as single or multiple mutations) was not correlated with reduced leukaemia-free survival or indeed overall survival, with the exception of mutations in

SRSF2, associated with reduced survival [

178,

179].

As the molecular profile of post-PV MF was shown to be considerably different from PMF [

180], the Myelofibrosis Secondary to PV and ET Prognostic Model (MYSEC-PM) was specifically developed to predict survival in post-PV/post-ET MF () [

181].

Table 4. Stratification of risk of survival in post-PV MF according to the Myelofibrosis Secondary to PV and ET Prognostic Model (MYSEC-PM) (adapted from [

181]). Patients are classified into low (score 0–10), intermediate 1 (score 11–13), intermediate 2 (score 14–15) or high (score > 16) risk groups. The MYSEC-PM is available online as a risk calculator (

http://www.mysec-pm.eu/, accessed on 2 November 2020).

| Risk Factor |

Score |

| Haemoglobin < 11 g/dL |

2 |

| Circulating blasts ≥3% |

2 |

| CALR-unmutated 1 |

2 |

| Platelets < 150 × 109/L |

1 |

| Constitutional symptoms |

1 |

| Age |

0.15 per year |

The score was shown to more effectively assess prognosis in post-PV MF patients, with poor agreement for risk classification between the DIPSS and MYSEC-PM scores when applied to the same post-PV patients [

180,

182]. Therefore, the MYSEC-PM is the most appropriate prognostic score for post-PV MF patients rather than the International Prognostic Scoring System (IPSS) or Dynamic IPSS (DIPSS) scores, both of which were developed for PMF.

Interestingly, in a retrospective study of 376 patients with SMF, including 188 post-PV MF, monosomal karyotype (observed in 8.5% of the SMF patients studied) was associated with significantly worse survival, with a median of 2 years, independently of the MYSEC-PM risk group [

183].

In terms of blastic transformation, it is also clear that the genetic profile of patients with post-PV AML differs from that of

de novo AML. For example, mutations in

FLT3 and

NPM1 are very uncommon and the

JAK2V617F-positive clone is frequently lost in transformation to AML [

184,

185]. Moreover, abnormal karyotype is a risk factor for leukemic transformation in PV and ET [

145,

146,

147,

150], estimated to occur in 80% of PV cases that progress [

146].

In some cases, the transformation from PV to AML is associated with the loss of function of TP53 due to an acquired mutation in the

TP53 gene leading to clonal dominance [

85,

177,

186,

187,

188]. In fact, in a mouse model, the expression of

JAK2V617F in combination with the loss of TP53 was demonstrated to cause an AML phenotype [

188]. This result was reflected in a later NGS study, which observed that post-PV/-ET AML patients with a

TP53 mutation had a survival rate at 12 months of just 18% compared to 48% for patients without a

TP53 mutation [

187].

Other mutations associated with a higher risk of leukemic transformation include

ASXL1, EZH2, RUNX1 and

SRSF2 [

85,

130,

187,

189]. Indeed, a recent French study that investigated the time between diagnosis and leukemic progression in 49 patients with post-PV/ET AML (including 24 post-PV) observed that mutations in

IDH1/2, RUNX1, and

U2AF1 were associated with a shorter time to transformation, while mutations in the genes

TP53, NRAS, and

BCORL1 were associated with a longer time to transformation [

187]. Such mutations are often detectable at low allelic frequencies in earlier stages of the disease, while others may appear later in the progression [

186,

187,

188].

TET2 was also observed in some studies to be a gene whose mutation is associated with the leukemic transformation of PV patients. One study that investigated mutations in 63 patients with AML secondary to an MPN found that mutations in

TET2 were acquired at transformation in 43% of cases [

190], and the acquisition of mutations in

TET2 in patients with PV

JAK2V617F was associated with transformation to AML and reduced survival [

120]. Nevertheless, the prognostic impact of

TET2 mutations, and indeed other mutations associated with CHIP, is not entirely clear. For example, when the impact of additional mutations on the risk of leukemic transformation was investigated, the presence of >1 additional SNV was associated with a higher risk of leukemic transformation and this association was even higher when

TET2 SNVs were removed [

187]. Moreover, mutations in

ASXL1 were observed at similar allelic frequencies before and after transformation, suggesting that they may not contribute to the dominance of the emerging leukemic clone [

188].

One of the largest sequencing studies performed to date, on 2035 MPN patients (including 356 PV patients), identified eight genetic subgroups [

85]. The authors developed a sophisticated prognostic model based on 63 clinical and genomic variables to estimate a patient’s probability of leukemic transformation. These findings have now been adapted into a personalized risk calculator, available online (

https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/mpn-multistage/, accessed on 26 November 2020).