Bone morphogenetic protein-7 is (BMP-7) is a potent anti-inflammatory growth factor belonging to the Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-β) superfamily. It plays an important role in various biological processes, including embryogenesis, hematopoiesis, neurogenesis and skeletal morphogenesis. BMP-7 stimulates the target cells by binding to specific membrane-bound receptor BMPR 2 and transduces signals through mothers against decapentaplegic (Smads) and mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways. To date, rhBMP-7 has been used clinically to induce the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells bordering the bone fracture site into chondrocytes, osteoclasts, the formation of new bone via calcium deposition and to stimulate the repair of bone fracture. However, its use in cardiovascular diseases, such as atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and diabetic cardiomyopathy is currently being explored. More importantly, these cardiovascular diseases are associated with inflammation and infiltrated monocytes where BMP-7 has been demonstrated to be a key player in the differentiation of pro-inflammatory monocytes, or M1 macrophages, into anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, which reduces developed cardiac dysfunction.

- atherosclerosis

- myocardial infarction

- diabetic cardiomyopathy

- inflammation

1. Introduction

| Types | Alternate Names | Tissues that Express | Functions | Receptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMP-1 | BMP-1 is a metalloproteinase | major end organs (heart, lung, liver, pancreas, kidney, and brain), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, thymus, spleen and lymph nodes), exocrine glands (prostate and mammary gland) organ protectors (muscle and bone) | Metalloprotease that cleaves COOH–propeptides of procollagens I, II, and III/induces cartilage formation/cleaves BMP antagonist chordin |

_____ |

| BMP-2 | BMP-2A, XBMP2, xBMP-2, MGC114605 |

major end organs (lung, pancreas, and kidney), lymphoid organ (spleen) | Induces bone and cartilage formation. Plays a role in skeletal repair and regeneration/heart formation | ALK-2, 3, 6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-3a & 3b |

Osteogenin, BMP-3A |

major end organs (brain, heart, pancreas), exocrine gland (prostate), organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, spleen and thymus), BMP-3b also expresses in spinal cord |

Negative regulator of bone morphogenesis Cell differentiation regulation; skeletal morphogenesis; Regulates cell growth and differentiation in both embryonic and adult tissues |

ALK-4 ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-4 | BMP-2B, BMP2B1, ZYME, OFC11, MCOPS6 |

major end organs (brain, heart, pancreas, liver, lung, kidney), exocrine gland (prostate), organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, spleen and thymus), spinal cord | Skeletal repair and regeneration; kidney formation; Induces cartilage and bone formation; limb formation; tooth development. | ALK-2,3,5,6 BMPR-II, ActR-IIA |

| BMP-5 | MGC34244 | major end organs (brain, heart, pancreas, liver, lung, kidney), exocrine gland (prostate), organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, spleen and thymus), spinal cord | Limb development; induces bone and cartilage morphogenesis; connecting soft tissues | ALK-3 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-6 | Vgr1, DVR-6 | major end organs (brain, heart, pancreas, liver, lung, kidney); exocrine gland (prostate); organ protector (muscle and bone), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, spleen and thymus); spinal cord |

Cartilage hypertrophy; bone morphogenesis; nervous system development; Plays a role in early development | ALK-2, 3, 6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-7 | OP-1 | major end organs (brain, heart, pancreas, liver, lung, kidney), exocrine gland (prostate) organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (bone marrow, spleen and thymus), spinal cord. | Skeletal repair and regeneration; kidney and eye formation; nervous system development plays a major role in calcium regulation and bone homeostasis |

ALK 2, 3, 6 BMPR-II; |

| BMP-8a & 8b |

OP-2, FLJ14351, FLJ45264 OP-3, PC-8, MGC131757 |

major end organs (brain, heart, kidney, lung, liver, pancreas), exocrine gland (prostate), organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (spleen, thymus bone marrow) spinal cord | Induces cartilage formation; Bone morphogenesis and spermatogenesis; calcium regulation and bone homeostasis. | ALK 2; 3; 4; 6; 7 BMPR-II; ALK3,6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-9 | GDF-2 | major end organ (liver) | Bone morphogenesis; cholinergic neurons development; in glucose metabolism; potent inhibitor of angiogenesis |

ALK-1,2 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-10 | MGC126783 | major end organs (brain, heart, kidney, lung, liver, pancreas), exocrine gland (prostate), organ protector (skeletal muscle), lymphoid organs (spleen, thymus, bone marrow) spinal cord. | Heart morphogenesis maintains the proliferative activity of embryonic cardiomyocytes by preventing premature activation of the negative cell cycle regulator; inhibits endothelial cell migration and growth |

ALK-1, 3, 6 ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-11 | GDF-11 | major end organs (brain, pancreas), exocrine gland (prostate), lymphoid organs (spleen, thymus bone marrow) spinal cord. | Pattering mesodermal and neural tissues, dentin formation | ALK-3, 4, 5, 7 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-12 | GDF-7, CDMP-3 | _____ | Ligament and tendon development/sensory neuron development | ALK-3, 6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA |

| BMP-13 | GDF-6, CDMP-2, KFS, KFSL, SGM1, MGC158100, MGC158101 |

_____ | Normal formation of bones and joins; skeletal morphogenesis and chondrogenesis Plays a key role in establishing boundaries between skeletal elements during development |

ALK-3, 6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA, ActR-IIB |

| BMP-14 | GDF-5, CDMP-1, OS5, LAP4, SYNS2, MP52 |

sensory organs (eye, skin), major end organs (brain, heart; kidney, liver, lung), embryonic tissue, mixed connective tissue, pituitary gland, salivary gland; exocrine gland (prostate), reproductive system related (uterus), lymphoid organ (bone marrow) | Bone and cartilage formation; Skeletal repair and regeneration |

ALK-3, 6 BMPR-II; ActR-IIA |

| BMP-15 | GDF-9B, ODG2, POF4 | _______ | Oocyte and follicular development | ALK-6 |

| BMP-16 | _____ | embryonic tissue; reproductive system (testis) |

Skeletal repair and regeneration Essential for mesoderm formation and axial patterning during embryonic development |

_____ |

| BMP-17 | _____ | major end organ (brain, lung, liver, pancreas, spleen) lymphoid organ (lymph node); exocrine gland (mammary gland); sensory organ (skin); reproductive organ (testis); bladder; embryonic tissue; intestine; joints; | Required for left-right axis determination as a regulator of LEFTY2 and NODAL | _____ |

| BMP-18 | _____ | major end organ (brain), embryonic tissue, reproductive system (testis) |

Required for left-right (L-R) asymmetry determination of organ systems in mammals. May play a role in endometrial bleeding | _____ |

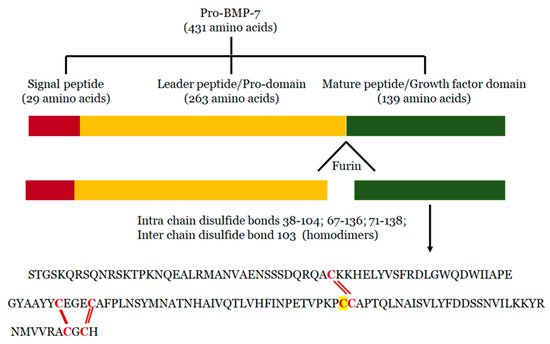

2. Structure of BMP-7

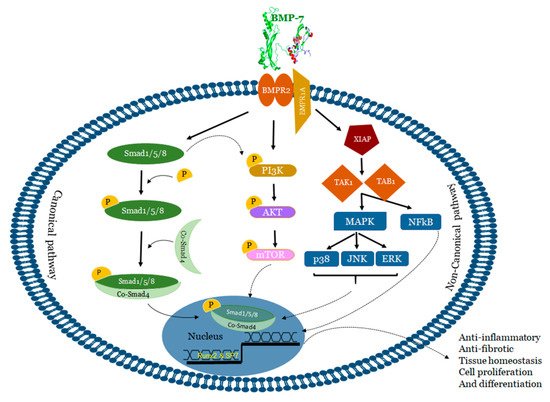

3. Mechanisms of BMP-7

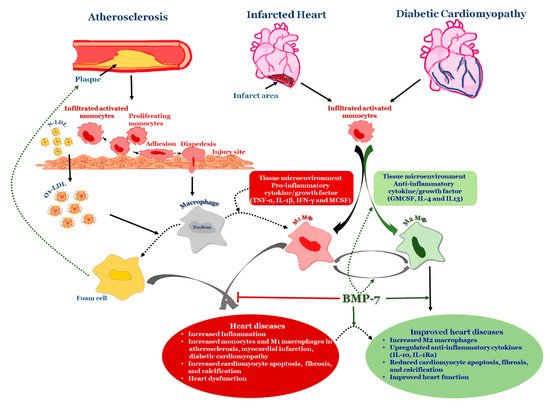

4. BMP-7 as an Anti-Inflammatory Agent in Atherosclerosis

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cells9020280

References

- Mazerbourg, S.; Hsueh, A.J. Genomic analyses facilitate identification of receptors and signalling pathways for growth differentiation factor 9 and related orphan bone morphogenetic protein/growth differentiation factor ligands. Hum. Reprod. Update 2006, 12, 373–383.

- Von Bubnoff, A.; Cho, K.W. Intracellular BMP signaling regulation in vertebrates: Pathway or network? Dev. Biol. 2001, 239, 1–14.

- Bragdon, B.; Moseychuk, O.; Saldanha, S.; King, D.; Julian, J.; Nohe, A. Bone morphogenetic proteins: A critical review. Cell. Signal. 2011, 23, 609–620.

- Miyazono, K.; Maeda, S.; Imamura, T. BMP receptor signaling: Transcriptional targets, regulation of signals, and signaling cross-talk. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2005, 16, 251–263.

- Xiao, Y.T.; Xiang, L.X.; Shao, J.Z. Bone morphogenetic protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 362, 550–553.

- Chen, D.; Ji, X.; Harris, M.A.; Feng, J.Q.; Karsenty, G.; Celeste, A.J.; Rosen, V.; Mundy, G.R.; Harris, S.E. Differential Roles for Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP) Receptor Type IB and IA in Differentiation and Specification of Mesenchymal Precursor Cells to Osteoblast and Adipocyte Lineages. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 142, 295–305.

- Chen, G.; Deng, C.; Li, Y.P. TGF-beta and BMP signaling in osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2012, 8, 272–288.

- Takada, I.; Kouzmenko, A.P.; Kato, S. PPAR-gamma Signaling Crosstalk in Mesenchymal Stem Cells. PPAR Res. 2010, 2010.

- Hata, K.; Nishimura, R.; Ikeda, F.; Yamashita, K.; Matsubara, T.; Nokubi, T.; Yoneda, T. Differential roles of Smad1 and p38 kinase in regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activating receptor gamma during bone morphogenetic protein 2-induced adipogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003, 14, 545–555.

- Kang, Q.; Song, W.X.; Luo, Q.; Tang, N.; Luo, J.; Luo, X.; Chen, J.; Bi, Y.; He, B.C.; Park, J.K.; et al. A comprehensive analysis of the dual roles of BMPs in regulating adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2009, 18, 545–559.

- Dorman, L.J.; Tucci, M.; Benghuzzi, H. In vitro effects of bmp-2, bmp-7, and bmp-13 on proliferation and differentation of mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2012, 48, 81–87.

- Reid, J.; Gilmour, H.M.; Holt, S. Primary non-specific ulcer of the small intestine. J. R. Coll. Surg. Edinb. 1982, 27, 228–232.

- Varkey, M.; Kucharski, C.; Haque, T.; Sebald, W.; Uludag, H. In vitro osteogenic response of rat bone marrow cells to bFGF and BMP-2 treatments. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006, 443, 113–123.

- Granjeiro, J.M.; Oliveira, R.C.; Bustos-Valenzuela, J.C.; Sogayar, M.C.; Taga, R. Bone morphogenetic proteins: From structure to clinical use. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. Rev. Bras. Pesqui. Med. Biol. 2005, 38, 1463–1473.

- Qian, S.W.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Huang, H.Y.; Xue, R.D.; Yu, H.Y.; Guo, L.; Gao, H.D.; et al. BMP4-mediated brown fat-like changes in white adipose tissue alter glucose and energy homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, E798–E807.

- Kalluri, R.; Zeisberg, M. Fibroblasts in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 392–401.

- Friedrichs, M.; Wirsdoerfer, F.; Flohe, S.B.; Schneider, S.; Wuelling, M.; Vortkamp, A. BMP signaling balances proliferation and differentiation of muscle satellite cell descendants. BMC Cell Biol. 2011, 12, 26.

- Segklia, A.; Seuntjens, E.; Elkouris, M.; Tsalavos, S.; Stappers, E.; Mitsiadis, T.A.; Huylebroeck, D.; Remboutsika, E.; Graf, D. Bmp7 regulates the survival, proliferation, and neurogenic properties of neural progenitor cells during corticogenesis in the mouse. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34088.

- Zhang, H.; Bradley, A. Mice deficient for BMP2 are nonviable and have defects in amnion/chorion and cardiac development. Development 1996, 122, 2977–2986.

- Winnier, G.; Blessing, M.; Labosky, P.A.; Hogan, B.L. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 is required for mesoderm formation and patterning in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2105–2116.

- Chen, H.; Shi, S.; Acosta, L.; Li, W.; Lu, J.; Bao, S.; Chen, Z.; Yang, Z.; Schneider, M.D.; Chien, K.R.; et al. BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development 2004, 131, 2219–2231.

- Dudley, A.T.; Lyons, K.M.; Robertson, E.J. A requirement for bone morphogenetic protein-7 during development of the mammalian kidney and eye. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2795–2807.

- McPherron, A.C.; Lawler, A.M.; Lee, S.J. Regulation of anterior/posterior patterning of the axial skeleton by growth/differentiation factor 11. Nat. Genet. 1999, 22, 260–264.

- Komatsu, Y.; Scott, G.; Nagy, A.; Kaartinen, V.; Mishina, Y. BMP type I receptor ALK2 is essential for proper patterning at late gastrulation during mouse embryogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 2007, 236, 512–517.

- Beppu, H.; Kawabata, M.; Hamamoto, T.; Chytil, A.; Minowa, O.; Noda, T.; Miyazono, K. BMP type II receptor is required for gastrulation and early development of mouse embryos. Dev. Biol. 2000, 221, 249–258.

- Mishina, Y.; Suzuki, A.; Ueno, N.; Behringer, R.R. Bmpr encodes a type I bone morphogenetic protein receptor that is essential for gastrulation during mouse embryogenesis. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 3027–3037.

- Sirard, C.; de la Pompa, J.L.; Elia, A.; Itie, A.; Mirtsos, C.; Cheung, A.; Hahn, S.; Wakeham, A.; Schwartz, L.; Kern, S.E.; et al. The tumor suppressor gene Smad4/Dpc4 is required for gastrulation and later for anterior development of the mouse embryo. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 107–119.

- Chang, H.; Huylebroeck, D.; Verschueren, K.; Guo, Q.; Matzuk, M.M.; Zwijsen, A. Smad5 knockout mice die at mid-gestation due to multiple embryonic and extraembryonic defects. Development 1999, 126, 1631–1642.

- Lechleider, R.J.; Ryan, J.L.; Garrett, L.; Eng, C.; Deng, C.; Wynshaw-Boris, A.; Roberts, A.B. Targeted mutagenesis of Smad1 reveals an essential role in chorioallantoic fusion. Dev. Biol. 2001, 240, 157–167.

- Chen, Q.; Chen, H.; Zheng, D.; Kuang, C.; Fang, H.; Zou, B.; Zhu, W.; Bu, G.; Jin, T.; Wang, Z.; et al. Smad7 is required for the development and function of the heart. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 292–300.

- Goldman, D.C.; Bailey, A.S.; Pfaffle, D.L.; Al Masri, A.; Christian, J.L.; Fleming, W.H. BMP4 regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood 2009, 114, 4393–4401.

- Ma, L.; Lu, M.F.; Schwartz, R.J.; Martin, J.F. Bmp2 is essential for cardiac cushion epithelial-mesenchymal transition and myocardial patterning. Development 2005, 132, 5601–5611.

- Rivera-Feliciano, J.; Tabin, C.J. Bmp2 instructs cardiac progenitors to form the heart-valve-inducing field. Dev. Biol. 2006, 295, 580–588.

- Dimitriou, R.; Tsiridis, E.; Giannoudis, P.V. Current concepts of molecular aspects of bone healing. Injury 2005, 36, 1392–1404.

- Carreira, A.C.; Alves, G.G.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Sogayar, M.C.; Granjeiro, J.M. Bone Morphogenetic Proteins: Structure, biological function and therapeutic applications. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 561, 64–73.

- Kim, M.; Choe, S. BMPs and their clinical potentials. BMB Rep. 2011, 44, 619–634.

- Reddi, A.H. Bone morphogenetic proteins: From basic science to clinical applications. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2001, 83.

- Geesink, R.G.; Hoefnagels, N.H.; Bulstra, S.K. Osteogenic activity of OP-1 bone morphogenetic protein (BMP-7) in a human fibular defect. J. Bone Jt. Surg. British Vol. 1999, 81, 710–718.

- Friedlaender, G.E.; Perry, C.R.; Cole, J.D.; Cook, S.D.; Cierny, G.; Muschler, G.F.; Zych, G.A.; Calhoun, J.H.; LaForte, A.J.; Yin, S. Osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) in the treatment of tibial nonunions. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. Vol. 2001, 83, 151–158.

- Cummings, S.R.; Melton, L.J. Epidemiology and outcomes of osteoporotic fractures. Lancet 2002, 359, 1761–1767.

- Giannoudis, P.; Tzioupis, C.; Almalki, T.; Buckley, R. Fracture healing in osteoporotic fractures: Is it really different? A basic science perspective. Injury 2007, 38, 90–99.

- Qaseem, A.; Snow, V.; Shekelle, P.; Hopkins, R., Jr.; Forciea, M.A.; Owens, D.K. Pharmacologic treatment of low bone density or osteoporosis to prevent fractures: A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2008, 149, 404–415.

- Chen, D.; Zhao, M.; Mundy, G.R. Bone morphogenetic proteins. Growth Factors 2004, 22, 233–241.

- Nakase, T.; Yoshikawa, H. Potential roles of bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) in skeletal repair and regeneration. J. Bone Miner. Metab. 2006, 24, 425–433.

- Ten Dijke, P.; Yamashita, H.; Sampath, T.K.; Reddi, A.H.; Estevez, M.; Riddle, D.L.; Ichijo, H.; Heldin, C.H.; Miyazono, K. Identification of type I receptors for osteogenic protein-1 and bone morphogenetic protein-4. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269, 16985–16988.

- Hahn, G.V.; Cohen, R.B.; Wozney, J.M.; Levitz, C.L.; Shore, E.M.; Zasloff, M.A.; Kaplan, F.S. A bone morphogenetic protein subfamily: Chromosomal localization of human genes for BMP5, BMP6, and BMP7. Genomics 1992, 14, 759–762.

- Nonner, D.; Barrett, E.F.; Kaplan, P.; Barrett, J.N. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMP6 and BMP7) enhance the protective effect of neurotrophins on cultured septal cholinergic neurons during hypoglycemia. J. Neurochem. 2001, 77, 691–699.

- Solloway, M.J.; Dudley, A.T.; Bikoff, E.K.; Lyons, K.M.; Hogan, B.L.; Robertson, E.J. Mice lacking Bmp6 function. Dev. Genet. 1998, 22, 321–339.

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, G.; Greenspan, D.S. Inhibition of Bone Morphogenetic Protein 1 by Native and Altered Forms of α2-Macroglobulin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 39096–39104.

- Luo, G.; Hofmann, C.; Bronckers, A.; Sohocki, M.; Bradley, A.; Karsenty, G. BMP-7 is an inducer of nephrogenesis, and is also required for eye development and skeletal patterning. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 2808–2820.

- Bustos-Valenzuela, J.C.; Halcsik, E.; Bassi, E.J.; Demasi, M.A.; Granjeiro, J.M.; Sogayar, M.C. Expression, purification, bioactivity, and partial characterization of a recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-7 produced in human 293T cells. Mol. Biotechnol. 2010, 46, 118–126.

- Swencki-Underwood, B.; Mills, J.K.; Vennarini, J.; Boakye, K.; Luo, J.; Pomerantz, S.; Cunningham, M.R.; Farrell, F.X.; Naso, M.F.; Amegadzie, B. Expression and characterization of a human BMP-7 variant with improved biochemical properties. Protein Expr. Purif. 2008, 57, 312–319.

- Isaacs, N.W. Cystine knots. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 1995, 5, 391–395.

- Sieber, C.; Kopf, J.; Hiepen, C.; Knaus, P. Recent advances in BMP receptor signaling. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2009, 20, 343–355.

- Little, S.C.; Mullins, M.C. Bone morphogenetic protein heterodimers assemble heteromeric type I receptor complexes to pattern the dorsoventral axis. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2009, 11, 637–643.

- Aono, A.; Hazama, M.; Notoya, K.; Taketomi, S.; Yamasaki, H.; Tsukuda, R.; Sasaki, S.; Fujisawa, Y. Potent ectopic bone-inducing activity of bone morphogenetic protein-4/7 heterodimer. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 210, 670–677.

- Hazama, M.; Aono, A.; Ueno, N.; Fujisawa, Y. Efficient expression of a heterodimer of bone morphogenetic protein subunits using a baculovirus expression system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 209, 859–866.

- Israel, D.I.; Nove, J.; Kerns, K.M.; Kaufman, R.J.; Rosen, V.; Cox, K.A.; Wozney, J.M. Heterodimeric bone morphogenetic proteins show enhanced activity in vitro and in vivo. Growth Factors 1996, 13, 291–300.

- Dimitriou, R.; Dahabreh, Z.; Katsoulis, E.; Matthews, S.J.; Branfoot, T.; Giannoudis, P.V. Application of recombinant BMP-7 on persistent upper and lower limb non-unions. Injury 2005, 36, 51–59.

- Nishimatsu, S.; Thomsen, G.H. Ventral mesoderm induction and patterning by bone morphogenetic protein heterodimers in Xenopus embryos. Mech. Dev. 1998, 74, 75–88.

- Schmid, B.; Furthauer, M.; Connors, S.A.; Trout, J.; Thisse, B.; Thisse, C.; Mullins, M.C. Equivalent genetic roles for bmp7/snailhouse and bmp2b/swirl in dorsoventral pattern formation. Development 2000, 127, 957–967.

- Suzuki, A.; Kaneko, E.; Maeda, J.; Ueno, N. Mesoderm induction by BMP-4 and -7 heterodimers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 232, 153–156.

- Kim, H.-S.; Neugebauer, J.; McKnite, A.; Tilak, A.; Christian, J.L. BMP7 functions predominantly as a heterodimer with BMP2 or BMP4 during mammalian embryogenesis. BioRxiv 2019, 686758.

- Vaccaro, A.R.; Whang, P.G.; Patel, T.; Phillips, F.M.; Anderson, D.G.; Albert, T.J.; Hilibrand, A.S.; Brower, R.S.; Kurd, M.F.; Appannagari, A.; et al. The safety and efficacy of OP-1 (rhBMP-7) as a replacement for iliac crest autograft for posterolateral lumbar arthrodesis: Minimum 4-year follow-up of a pilot study. Spine J. 2008, 8, 457–465.

- Boon, M.R.; van der Horst, G.; van der Pluijm, G.; Tamsma, J.T.; Smit, J.W.; Rensen, P.C. Bone morphogenetic protein 7: A broad-spectrum growth factor with multiple target therapeutic potency. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2011, 22, 221–229.

- Carreira, A.C.; Lojudice, F.H.; Halcsik, E.; Navarro, R.D.; Sogayar, M.C.; Granjeiro, J.M. Bone morphogenetic proteins: Facts, challenges, and future perspectives. J. Dent. Res. 2014, 93, 335–345.

- Rocher, C.; Singla, R.; Singal, P.K.; Parthasarathy, S.; Singla, D.K. Bone morphogenetic protein 7 polarizes THP-1 cells into M2 macrophages. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012, 90, 947–951.

- Cecchi, S.; Bennet, S.J.; Arora, M. Bone morphogenetic protein-7: Review of signalling and efficacy in fracture healing. J. Orthop. Translat. 2015, 4, 28–34.

- Singla, D.K.; Singla, R.; Wang, J. BMP-7 Treatment Increases M2 Macrophage Differentiation and Reduces Inflammation and Plaque Formation in Apo E-/- Mice. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147897.

- Rocher, C.; Singla, D.K. SMAD-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway mediates BMP-7 polarization of monocytes into M2 macrophages. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84009.

- Shoulders, H.; Garner, K.H.; Singla, D.K. Macrophage depletion by clodronate attenuates bone morphogenetic protein-7 induced M2 macrophage differentiation and improved systolic blood velocity in atherosclerosis. Transl. Res. 2019, 203, 1–14.

- Chattopadhyay, T.; Singh, R.R.; Gupta, S.; Surolia, A. Bone morphogenetic protein-7 (BMP-7) augments insulin sensitivity in mice with type II diabetes mellitus by potentiating PI3K/AKT pathway. Biofactors 2017, 43, 195–209.

- Rosenzweig, B.L.; Imamura, T.; Okadome, T.; Cox, G.N.; Yamashita, H.; ten Dijke, P.; Heldin, C.H.; Miyazono, K. Cloning and characterization of a human type II receptor for bone morphogenetic proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 7632–7636.

- Miyazono, K.; Kamiya, Y.; Morikawa, M. Bone morphogenetic protein receptors and signal transduction. J. Biochem. 2010, 147, 35–51.

- Ulsamer, A.; Ortuno, M.J.; Ruiz, S.; Susperregui, A.R.; Osses, N.; Rosa, J.L.; Ventura, F. BMP-2 induces Osterix expression through up-regulation of Dlx5 and its phosphorylation by p38. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 3816–3826.

- Franceschi, R.T.; Xiao, G. Regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor, Runx2: Responsiveness to multiple signal transduction pathways. J. Cell. Biochem. 2003, 88, 446–454.

- Lee, K.S.; Hong, S.H.; Bae, S.C. Both the Smad and p38 MAPK pathways play a crucial role in Runx2 expression following induction by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein. Oncogene 2002, 21, 7156–7163.

- Morrell, N.W.; Bloch, D.B.; ten Dijke, P.; Goumans, M.J.; Hata, A.; Smith, J.; Yu, P.B.; Bloch, K.D. Targeting BMP signalling in cardiovascular disease and anaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2016, 13, 106–120.

- Feng, X.H.; Derynck, R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 2005, 21, 659–693.

- Wu, M.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.P. TGF-beta and BMP signaling in osteoblast, skeletal development, and bone formation, homeostasis and disease. Bone Res. 2016, 4, 16009.

- Macias-Silva, M.; Hoodless, P.A.; Tang, S.J.; Buchwald, M.; Wrana, J.L. Specific activation of Smad1 signaling pathways by the BMP7 type I receptor, ALK2. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 25628–25636.

- Pal, R.; Khanna, A. Role of smad- and wnt-dependent pathways in embryonic cardiac development. Stem Cells Dev. 2006, 15, 29–39.

- Ebisawa, T.; Tada, K.; Kitajima, I.; Tojo, K.; Sampath, T.K.; Kawabata, M.; Miyazono, K.; Imamura, T. Characterization of bone morphogenetic protein-6 signaling pathways in osteoblast differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 1999, 112, 3519–3527.

- Lavery, K.; Hawley, S.; Swain, P.; Rooney, R.; Falb, D.; Alaoui-Ismaili, M.H. New insights into BMP-7 mediated osteoblastic differentiation of primary human mesenchymal stem cells. Bone 2009, 45, 27–41.

- Yeh, L.C.; Tsai, A.D.; Lee, J.C. Osteogenic protein-1 (OP-1, BMP-7) induces osteoblastic cell differentiation of the pluripotent mesenchymal cell line C2C12. J. Cell Biochem. 2002, 87, 292–304.

- Zhang, J.; Li, L. BMP signaling and stem cell regulation. Dev. Biol. 2005, 284, 1–11.

- Herpin, A.; Cunningham, C. Cross-talk between the bone morphogenetic protein pathway and other major signaling pathways results in tightly regulated cell-specific outcomes. FEBS J. 2007, 274, 2977–2985.

- Yamaguchi, K.; Nagai, S.; Ninomiya-Tsuji, J.; Nishita, M.; Tamai, K.; Irie, K.; Ueno, N.; Nishida, E.; Shibuya, H.; Matsumoto, K. XIAP, a cellular member of the inhibitor of apoptosis protein family, links the receptors to TAB1-TAK1 in the BMP signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 179–187.

- Chen, J.C.; Yang, S.T.; Lin, C.Y.; Hsu, C.J.; Tsai, C.H.; Su, J.L.; Tang, C.H. BMP-7 enhances cell migration and αvβ3 integrin expression via a c-Src-dependent pathway in human chondrosarcoma cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112636.

- Yeh, C.H.; Chang, C.K.; Cheng, M.F.; Lin, H.J.; Cheng, J.T. The antioxidative effect of bone morphogenetic protein-7 against high glucose-induced oxidative stress in mesangial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 382, 292–297.

- Yeh, L.C.; Ma, X.; Matheny, R.W.; Adamo, M.L.; Lee, J.C. Protein kinase D mediates the synergistic effects of BMP-7 and IGF-I on osteoblastic cell differentiation. Growth Factors 2010, 28, 318–328.

- Klatte-Schulz, F.; Giese, G.; Differ, C.; Minkwitz, S.; Ruschke, K.; Puts, R.; Knaus, P.; Wildemann, B. An investigation of BMP-7 mediated alterations to BMP signalling components in human tenocyte-like cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 29703.

- Hu, M.C.; Wasserman, D.; Hartwig, S.; Rosenblum, N.D. p38MAPK acts in the BMP7-dependent stimulatory pathway during epithelial cell morphogenesis and is regulated by Smad1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 12051–12059.

- Blank, U.; Brown, A.; Adams, D.C.; Karolak, M.J.; Oxburgh, L. BMP7 promotes proliferation of nephron progenitor cells via a JNK-dependent mechanism. Development 2009, 136, 3557–3566.

- Sovershaev, T.A.; Egorina, E.M.; Unruh, D.; Bogdanov, V.Y.; Hansen, J.B.; Sovershaev, M.A. BMP-7 induces TF expression in human monocytes by increasing F3 transcriptional activity. Thromb. Res. 2015, 135, 398–403.

- Shimizu, T.; Kayamori, T.; Murayama, C.; Miyamoto, A. Bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-4 and BMP-7 suppress granulosa cell apoptosis via different pathways: BMP-4 via PI3K/PDK-1/Akt and BMP-7 via PI3K/PDK-1/PKC. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 417, 869–873.

- Weichhart, T.; Saemann, M.D. The PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in innate immune cells: Emerging therapeutic applications. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 70–74.

- Rauh, M.J.; Ho, V.; Pereira, C.; Sham, A.; Sly, L.M.; Lam, V.; Huxham, L.; Minchinton, A.I.; Mui, A.; Krystal, G. SHIP represses the generation of alternatively activated macrophages. Immunity 2005, 23, 361–374.

- Glass, C.K.; Witztum, J.L. Atherosclerosis. the road ahead. Cell 2001, 104, 503–516.

- Libby, P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 2002, 420, 868–874.

- Hansson, G.K. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 352, 1685–1695.

- Bentzon, J.F.; Otsuka, F.; Virmani, R.; Falk, E. Mechanisms of plaque formation and rupture. Circ. Res. 2014, 114, 1852–1866.

- Parthasarathy, S. Modified Lipoproteins in the Pathogenesis of Atherosclerosis; RG Landes Co: Austin, TX, USA, 1994.

- Steinberg, D. Thematic review series: The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: An interpretive history of the cholesterol controversy, part III: Mechanistically defining the role of hyperlipidemia. J. Lipid. Res. 2005, 46, 2037–2051.

- Galkina, E.; Ley, K. Leukocyte influx in atherosclerosis. Curr. Drug Targets 2007, 8, 1239–1248.

- Weber, C.; Zernecke, A.; Libby, P. The multifaceted contributions of leukocyte subsets to atherosclerosis: Lessons from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 802–815.

- Libby, P.; Lichtman, A.H.; Hansson, G.K. Immune effector mechanisms implicated in atherosclerosis: From mice to humans. Immunity 2013, 38, 1092–1104.

- Steven, S.; Frenis, K.; Oelze, M.; Kalinovic, S.; Kuntic, M.; Bayo Jimenez, M.T.; Vujacic-Mirski, K.; Helmstädter, J.; Kröller-Schön, S.; Münzel, T.; et al. Vascular Inflammation and Oxidative Stress: Major Triggers for Cardiovascular Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 26.

- Steinberg, D.; Witztum, J.L. Lipoproteins and atherogenesis. Current concepts. Jama 1990, 264, 3047–3052.

- Ross, R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: A perspective for the 1990s. Nature 1993, 362, 801–809.

- Swirski, F.K.; Pittet, M.J.; Kircher, M.F.; Aikawa, E.; Jaffer, F.A.; Libby, P.; Weissleder, R. Monocyte accumulation in mouse atherogenesis is progressive and proportional to extent of disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10340–10345.

- Hahn, C.; Schwartz, M.A. Mechanotransduction in vascular physiology and atherogenesis. Na. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 53–62.

- Bi, Y.; Chen, J.; Hu, F.; Liu, J.; Li, M.; Zhao, L. M2 Macrophages as a Potential Target for Antiatherosclerosis Treatment. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 21.

- Van Tits, L.J.; Stienstra, R.; van Lent, P.L.; Netea, M.G.; Joosten, L.A.; Stalenhoef, A.F. Oxidized LDL enhances pro-inflammatory responses of alternatively activated M2 macrophages: A crucial role for Kruppel-like factor 2. Atherosclerosis 2011, 214, 345–349.

- Martinon, F. Signaling by ROS drives inflammasome activation. Eur. J. Immunol. 2010, 40, 616–619.

- Chinetti-Gbaguidi, G.; Baron, M.; Bouhlel, M.A.; Vanhoutte, J.; Copin, C.; Sebti, Y.; Derudas, B.; Mayi, T.; Bories, G.; Tailleux, A.; et al. Human atherosclerotic plaque alternative macrophages display low cholesterol handling but high phagocytosis because of distinct activities of the PPARgamma and LXRalpha pathways. Circ. Res. 2011, 108, 985–995.