Macrophages are innate immune cells pivotal for tissue homeostasis, removal of superfluous cells, and inflammatory responses to infections. Macrophages also play diverse roles in cancer development, ranging from antitumor activity in early progression stages to, most commonly, tumor-promoting roles in established cancer. Notably, macrophages are highly plastic cells and, depending on the microenvironmental cues in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME), can undergo marked changes in their function. In established cancers, high macrophage infiltration often strongly associates with poor prognosis or tumor progression in many types of solid tumors, including breast, bladder, head and neck, glioma, melanoma, and prostate cancer. Conversely, in colorectal and gastric cancers, high macrophage infiltration correlates with a better prognosis. These apparently opposite effects are likely related to macrophage plasticity and resultant heterogeneity of phenotype and functions in various cancers.

- tumor-associated macrophages

- immunotherapy

- tumor microenvironment

- tumor

- immune suppression

- macrophage

1. The Role of Macrophages in the Tumor-Promoting Inflammation

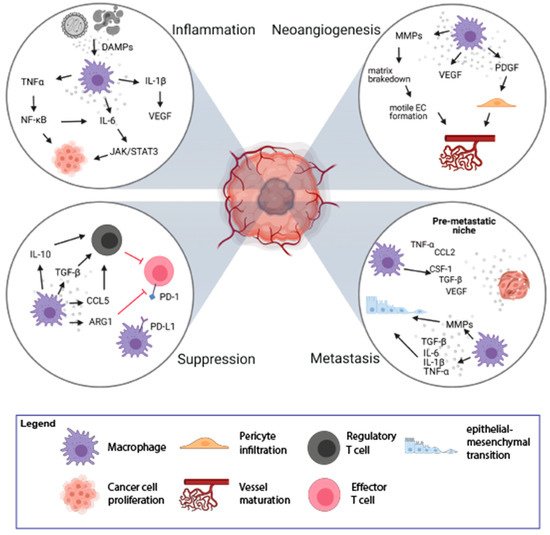

In a physiological context, inflammation is initiated to restore homeostasis after the disturbance caused by external factors [1]. However, not every type of inflammation is advantageous, and chronic inflammation increases the chances for the transformation into a malignant cell. Tumor-promoting inflammation could be induced long before tumor formation and can support tumor growth by encouraging neoangiogenesis, immune suppression, and oncogenic mutations [2]. Cell death is frequent in tumors and leads to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), like High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1), Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs), or ATP [3][4]. This stimulation can lead to the promotion of anti-tumor immunity, e.g., by activation of dendritic cells and macrophages. However, chronic stimulation will lead to immunosuppression mediated by increased production of IL-10, which inhibits the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and induces the formation of regulatory T lymphocytes (Tregs) [5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mechanisms of tumorigenesis stimulation by Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs). TAMs play an important role in the process of tumorigenesis by induction of inflammation (top left loop), stimulation of neoangiogenesis (top right loop), immune suppression (bottom left loop), and induction of metastasis (bottom right loop). The figure was created with Biorender.com.

Macrophages can contribute to tumor-promoting inflammation, e.g., by secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, like IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα. On the one hand, it can induce immune response but it can also support tumor growth and survival of malignant cells. TNFα, upon binding to its receptors (TNFR1/2), activates the nuclear factor -κB (NF-κB) pathway. NF-κB further mediates cancer cell proliferation and survival by controlling the expression of target genes (e.g., VEGF, IL-6) and stimulation of neoangiogenesis [6]. The proinflammatory effect of IL-6, mediated by the JAK/STAT3 pathway, leads to cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [1][7]. Proinflammatory cytokine, IL-1β, activates endothelial cells to produce VEGF, which supports angiogenesis, contributing to tumor invasiveness and metastasis. It also drives the expression of downstream pro-tumorigenic cytokines such as IL-6, TNFα, and TGFβ [8]. TGFβ is also produced by activated macrophages and plays a dual, pro-, or anti-inflammatory role [9][10]. In the early stages of tumor development, TGFβ promotes apoptosis and inhibits the progression of the cell cycle. In the later stages, TGFβ induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which enhances tumor invasion and metastasis. Increased TGFβ concentrations have an inhibitory effect on anti-tumor T-cell response [1][11]. Thus, TAMs could enhance tumor formation and progression by their inflammatory activity, particularly a chronic low-grade inflammatory state.

2. Macrophages and Neoangiogenesis

The rapid proliferation of cancer cells results in the fast growth of tumor mass and increased demand for nutrients and oxygen. Essential nutrients are delivered to the tumor by a capillary network formed in the process of neoangiogenesis. The formation of new vessels is regulated by the growth factors released by cells in the TME [12]. Due to poor regulation, the structure and function of newly formed vessels are abnormal with increased vessel permeability, which contributes to disease progression [13]. Hypoxic regions of tumor tissue are formed due to the rapid and uncontrolled cell growth and are accompanied by an increased rate of cancer cell death. TAMs infiltrate these hypoxic regions to regain homeostasis through stimulation of new blood vessel formation. The process of neoangiogenesis is modulated by many factors produced by TAMs, including VEGF, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and angiopoietin-1 (Figure 1) [14][15]. VEGF induces proliferation and maturation of endothelial cells by engaging the VEGF Receptor 2 (VEGFR2) expressed on the endothelial cells (ECs) [16]. VEGF also stimulates the chemotaxis of macrophages and ECs. This process is promoted by MMP-2, MMP-7, MMP-9, which are also secreted by TAMs. The main role of MMPs is to break down the extracellular matrix, which allows migration of ECs and the formation of new vascular sprouts [16]. Additionally, it facilitates the infiltration and invasion of adjacent tissues, which may also promote the formation of metastases [13].

TAMs and platelets are also the main sources of PDGF, which induces infiltration of pericytes [17]. The interaction between pericytes and ECs is crucial for vessel maturation and remodeling, which affects vascular permeability [18]. The angiopoietin-1 released from pericytes binds to Tie-2 receptor on ECs, leading to tightening of ECs’ cell-cell junctions and stabilization of newly formed vessels (Figure 1) [19].

It has been shown that a specific subset of monocytes expressing the Tie-2 receptor (Tie-2 receptor-expressing monocytes—TEMs) account for most of the proangiogenic activity of macrophages in both spontaneous and orthotopic tumors. TEMs are present in peripheral blood and are responsible for early angiogenic responses. Thus, it is thought that TEMs can be precursors of proangiogenic TAMs [20].

3. Immune Suppression and Orchestration of the Tumor Microenvironment by TAMs

The TME is infiltrated with various immune cells, out of which TAMs are the most abundant cell population. TAMs play a significant role in immunosuppression and tumor progression by releasing immunomodulatory factors such as PGE2, IL-10, and TGFβ, which inhibit cytotoxic activity of T lymphocytes and NK cells (Figure 1) [2][11]. Upon secretion of IL-10 and TGFβ, TAMs induce Tregs that suppress the activity of effector T lymphocytes. Moreover, TAMs recruit Tregs to the TME by secretion of chemokines CCL5, CCL20, and CCL22 [21]. Additionally, TAMs are involved in the conversion of Th cells into Tregs, which further inhibit the immune response in an antigen-specific manner [22].

The other mechanism of the suppression of the immune response can be mediated by direct cell-to-cell contact between macrophages and other immune cells. TAMs could directly inhibit the immune response by expression of surface proteins, PD-L1, CD80/CD86, or death receptor ligands, FasL or TRAIL, that function as agonists for inhibitory receptors, PD-1, CTLA-4, FAS, and TRAIL-RI/-RII, respectively, that are present on the immune effector cells [23][23]. The stimulation of PD-1 and CTLA-4 receptors leads to the inhibition of the signaling pathway from the T cell receptor (TCR) and causes a decrease in the production of cytokines and proteins that promote cell survival. PD-L1 expression has been observed on macrophages and dendritic cells in many cancer types [24] as well as on macrophages and myeloid-derived suppressor cells isolated from the hypoxic tumor regions [25]. Therefore, macrophages may modulate lymphocyte function and inhibit the antitumor immune response via PD-1/PD-L1 interaction [26]. TAMs also express CD80 and CD86, that upon binding to CTLA-4 on T lymphocytes, inhibit their activation [27]. Moreover, TAMs produce arginase-1—an enzyme degrading L-arginine, which is necessary for the expression of TCR complex, lymphocyte proliferation, development of the immunological memory [28], and T cell-mediated antitumor response [29]. L-arginine starvation leads to inhibition of T cell proliferation via Go–G1 phase blockade [30]. Thus, TAMs have pleiotropic immunosuppressive abilities that quench adaptive antitumor immunity.

4. TAMs in Tissue Invasion and Distant Metastasis

Colonization of distant organs by neoplastic cells is a multistep process. First, cancer cells acquire the ability to grow invasively; second, they penetrate the vasculature; third, they survive in the circulation; and last effectively settle in the new metastatic location [31]. TAMs are important players in almost every step of metastasis formation [31]. Activation of Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) on the surface of M2-like macrophages increases the level of IL-10, which promotes the EMT program, which plays an important role in the first steps of metastases [32]. EMT can also be induced by proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-1β, TNFα) [33] and TGFβ [34] released by TAMs (Figure 1). During the EMT, epithelial cells lose cell-cell junction and acquire motile and invasive mesenchymal cell phenotype facilitating the passage through dismounted basement membranes. TAMs are also involved in the breakdown of the extracellular membrane around endothelium by the release of MMP9 and cathepsins, which results in vascular intravasation of tumor cells. Additionally, there is a positive feedback loop between macrophages and tumor cells: CSF-1 produced by tumor cells stimulates macrophage motility and secretion of EGF, which in turn supports chemotaxis of tumor cells into blood vessels [35]. TAMs support the survival of cancer cells in the circulation by the interaction of α4 integrin with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) on the surface of cancer cells. This interaction activates the PI3K/Akt survival pathway protecting cancer cells from the pro-apoptotic activity of molecules such as TRAIL [36]. It was observed that tumor cells are in direct interaction with TAMs when crossing the endothelial cell layer into the blood vessel [37]. Interaction of macrophages with tumor cells enhances extravasation. Before metastasis is formed, local changes occur in the target tissue leading to the creation of a premetastatic niche. Increased influx of macrophages into healthy tissue is an important step preceding the formation of metastases. Macrophages are attracted to the circulation by various agents released from tumor cells, including CSF-1, CCL-2, VEGF, TNFα, or TGFβ, and accumulate at pre-metastatic sites [38]. Macrophages that appear in the site of future metastasis form migration tracks for cancer cells by remodeling of collagen fibers, which facilitates the invasion of cancer cells [39]. TAMs shape the extracellular matrix by releasing growth factors deposited in the extracellular matrix, which results in the stimulation of neoangiogenesis, extravasation, and EMT [31]. The above-mentioned processes show the role of TAMs in the enhancement of local tumor cell migration and distant metastasis formation.

5. The Role of M1 TAMs in the Elimination of Cancer Cells

Although the M2 TAMs play an important role in tumor development, M1 TAMs have been shown to effectively eliminate cancer cells. M1 polarized macrophages drive Th responses via antigen presentation more efficiently than M2 macrophages, including T cell proliferation and IFNγ secretion [40]. IFNγ-stimulated macrophages secrete IL-12 [41], which is a proinflammatory cytokine with potent antitumor activity [42] and the ability to recover costimulatory properties of TAMs for T cells [41]. M1 macrophages also secrete less VEGF, MMPs, and CCL18 than M2 macrophages [41]. What is more, TLR ligands (e.g., LPS) either alone or together with IFNγ drive M1 polarization, which further leads to the inhibition of cancer cell growth [43]. Therefore, M1 TAMs are considered tumor-suppressive, and M2 TAMs are considered tumor-promoting macrophages [44].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13081946

References

- Glauben Landskron; Marjorie De La Fuente; Peti Thuwajit; Chanitra Thuwajit; Marcela A. Hermoso; Chronic Inflammation and Cytokines in the Tumor Microenvironment. Journal of Immunology Research 2014, 2014, 1-19, 10.1155/2014/149185.

- Jing Wang; Danyang Li; Huaixing Cang; Bo Guo; Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: Role of tumor‐associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Medicine 2019, 8, 4709-4721, 10.1002/cam4.2327.

- Florian R. Greten; Sergei I. Grivennikov; Inflammation and Cancer: Triggers, Mechanisms, and Consequences. Immunity 2019, 51, 27-41, 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025.

- Ashleigh R. Poh; Matthias Ernst; Targeting Macrophages in Cancer: From Bench to Bedside. Frontiers in Oncology 2018, 8, 49, 10.3389/fonc.2018.00049.

- Rebecca S. Cook; Kristen M. Jacobsen; Anne M. Wofford; Deborah DeRyckere; Jamie Stanford; Anne L. Prieto; Elizabeth Redente; Melissa Sandahl; Debra M. Hunter; Karen E. Strunk; et al. MerTK inhibition in tumor leukocytes decreases tumor growth and metastasis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2013, 123, 3231-3242, 10.1172/jci67655.

- Longzheng Xia; Shiming Tan; Yujuan Zhou; Jingguan Lin; Heran Wang; Linda Oyang; Yutong Tian; Lu Liu; Min Su; Hui Wang; et al. Role of the NFκB-signaling pathway in cancer. OncoTargets and Therapy 2018, ume 11, 2063-2073, 10.2147/ott.s161109.

- Stephen J Thomas; J A Snowden; Martin P Zeidler; Sarah Danson; The role of JAK/STAT signalling in the pathogenesis, prognosis and treatment of solid tumours. British Journal of Cancer 2015, 113, 365-371, 10.1038/bjc.2015.233.

- Kevin J. Baker; Aileen Houston; Elizabeth Brint; IL-1 Family Members in Cancer; Two Sides to Every Story. Frontiers in Immunology 2019, 10, 1197, 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01197.

- Sergei I. Grivennikov; Florian R. Greten; Michael Karin; Immunity, Inflammation, and Cancer. Cell 2010, 140, 883-899, 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025.

- Lisa M. Coussens; Zena Werb; Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860-867, 10.1038/nature01322.

- Soyoung A. Oh; Ming O. Li; TGF-β: Guardian of T Cell Function. The Journal of Immunology 2013, 191, 3973-3979, 10.4049/jimmunol.1301843.

- Naoyo Nishida; Hirohisa Yano; Takashi Nishida; Toshiharu Kamura; Masamichi Kojiro; Angiogenesis in cancer. Vascular Health and Risk Management 2006, 2, 213-219, 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.3.213.

- Roberta Lugano; Mohanraj Ramachandran; Anna Dimberg; Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 77, 1745-1770, 10.1007/s00018-019-03351-7.

- D Ribatti; B Nico; E Crivellato; A Vacca; Macrophages and tumor angiogenesis. Leukemia 2007, 21, 2085-2089, 10.1038/sj.leu.2404900.

- Vladimir Riabov; Alexandru Gudima; Nan Wang; Amanda Mickley; Alexander Orekhov; Julia Kzhyshkowska; Role of tumor associated macrophages in tumor angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Frontiers in Physiology 2014, 5, 75, 10.3389/fphys.2014.00075.

- Saray Quintero-Fabián; Rodrigo Arreola; Enrique Becerril-Villanueva; Julio César Torres-Romero; Victor Arana-Argáez; Julio Lara-Riegos; Mario Alberto Ramírez-Camacho; María Elizbeth Alvarez-Sánchez; Role of Matrix Metalloproteinases in Angiogenesis and Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2019, 9, 1370, 10.3389/fonc.2019.01370.

- Victor Ljl Thijssen; Yvette Wj Paulis; Patrycja Nowak-Sliwinska; Katrin L Deumelandt; Kayoko Hosaka; Patricia Mmb Soetekouw; Anca M. Cimpean; Marius Raica; Patrick Pauwels; Joost J Van Den Oord; et al. Targeting PDGF-mediated recruitment of pericytes blocks vascular mimicry and tumor growth. The Journal of Pathology 2018, 246, 447-458, 10.1002/path.5152.

- Aline Lopes Ribeiro; Oswaldo Keith Okamoto; Combined Effects of Pericytes in the Tumor Microenvironment. Stem Cells International 2015, 2015, 1-8, 10.1155/2015/868475.

- Michele De Palma; Daniela Biziato; Tatiana V. Petrova; Microenvironmental regulation of tumour angiogenesis. Nature Cancer 2017, 17, 457-474, 10.1038/nrc.2017.51.

- Michele De Palma; Mary Anna Venneri; Rossella Galli; Lucia Sergi Sergi; Letterio S. Politi; Maurilio Sampaolesi; Luigi Naldini; Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell 2005, 8, 211-226, 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002.

- Kanako Shimizu; Tomonori Iyoda; Masahiro Okada; Satoru Yamasaki; Shin-Ichiro Fujii; Immune suppression and reversal of the suppressive tumor microenvironment. International Immunology 2018, 30, 445-455, 10.1093/intimm/dxy042.

- Dario A. A. Vignali; Lauren W. Collison; Creg J. Workman; How regulatory T cells work. Nature Reviews Immunology 2008, 8, 523-532, 10.1038/nri2343.

- Roy Noy; Jeffrey W. Pollard; Tumor-Associated Macrophages: From Mechanisms to Therapy. Immunity 2014, 41, 49-61, 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.010.

- Manuela Liguori; Chiara Buracchi; Fabio Pasqualini; Francesca Bergomas; Samantha Pesce; Marina Sironi; Fabio Grizzi; Alberto Mantovani; Cristina Belgiovine; Paola Allavena; et al. Functional TRAIL receptors in monocytes and tumor-associated macrophages: A possible targeting pathway in the tumor microenvironment. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 41662-41676, 10.18632/oncotarget.9340.

- Kurt Alex Schalper; Daniel Carvajal-Hausdorf; Joseph McLaughlin; Vamsidhar Velcheti; Lieping Chen; Miguel Sanmamed; Roy S Herbst; David L Rimm; Clinical significance of PD-L1 protein expression on tumor-associated macrophages in lung cancer. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer 2015, 3, P415-P415, 10.1186/2051-1426-3-s2-p415.

- Muhammad Zaeem Noman; Giacomo Desantis; Bassam Janji; Meriem Hasmim; Saoussen Karray; Philippe Dessen; Vincenzo Bronte; Salem Chouaib; PD-L1 is a novel direct target of HIF-1α, and its blockade under hypoxia enhanced MDSC-mediated T cell activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine 2014, 211, 781-790, 10.1084/jem.20131916.

- Andrew M. Intlekofer; Craig B. Thompson; At the Bench: Preclinical rationale for CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade as cancer immunotherapy. Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2013, 94, 25-39, 10.1189/jlb.1212621.

- K. Vandenborre; S. W. Van Gool; A. Kasran; J. L. Ceuppens; M. A. Boogaerts; P. Vandenberghe; Interaction of CTLA-4 (CD152) with CD80 or CD86 inhibits human T-cell activation. Immunology 1999, 98, 413-421, 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00888.x.

- Petar J. Popovic; Iii Herbert J. Zeh; Juan B. Ochoa; Arginine and Immunity. The Journal of Nutrition 2007, 137, 1681S-1686S, 10.1093/jn/137.6.1681s.

- Malgorzata Czystowska-Kuzmicz; Anna Sosnowska; Dominika Nowis; Kavita Ramji; Marta Szajnik; Justyna Chlebowska-Tuz; Ewa Wolinska; Pawel Gaj; Magdalena Grazul; Zofia Pilch; et al. Small extracellular vesicles containing arginase-1 suppress T-cell responses and promote tumor growth in ovarian carcinoma. Nature Communications 2019, 10, 1-16, 10.1038/s41467-019-10979-3.

- Paulo C. Rodriguez; David G. Quiceno; Augusto C. Ochoa; l-arginine availability regulates T-lymphocyte cell-cycle progression. Blood 2006, 109, 1568-1573, 10.1182/blood-2006-06-031856.

- Yuxin Lin; Jianxin Xu; Huiyin Lan; Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor metastasis: biological roles and clinical therapeutic applications. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2019, 12, 1-16, 10.1186/s13045-019-0760-3.

- Zhe Ge; Shuzhe Ding; The Crosstalk Between Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) and Tumor Cells and the Corresponding Targeted Therapy. Frontiers in Oncology 2020, 10, 1-23, 10.3389/fonc.2020.590941.

- Meggy Suarez-Carmona; Julien Lesage; Didier Cataldo; Christine Gilles; EMT and inflammation: inseparable actors of cancer progression. Molecular Oncology 2017, 11, 805-823, 10.1002/1878-0261.12095.

- Anne-Katrine Bonde; Verena Tischler; Sushil Kumar; Alex Soltermann; Reto A Schwendener; Intratumoral macrophages contribute to epithelial-mesenchymal transition in solid tumors. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 35-35, 10.1186/1471-2407-12-35.

- Jeffrey Wyckoff; Weigang Wang; Elaine Y. Lin; Yarong Wang; Fiona Pixley; E. Richard Stanley; Thomas Graf; Jeffrey W. Pollard; Jeffrey Segall; John Condeelis; et al. A Paracrine Loop between Tumor Cells and Macrophages Is Required for Tumor Cell Migration in Mammary Tumors. Cancer Research 2004, 64, 7022-7029, 10.1158/0008-5472.can-04-1449.

- Qing Chen; Xiang H.-F. Zhang; Joan Massagué; Macrophage Binding to Receptor VCAM-1 Transmits Survival Signals in Breast Cancer Cells that Invade the Lungs. Cancer Cell 2011, 20, 538-549, 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.08.025.

- Binzhi Qian; Yan Deng; Jae Hong Im; Ruth J. Muschel; Yiyu Zou; Jiufeng Li; Richard A. Lang; Jeffrey W. Pollard; A Distinct Macrophage Population Mediates Metastatic Breast Cancer Cell Extravasation, Establishment and Growth. PLOS ONE 2009, 4, e6562, 10.1371/journal.pone.0006562.

- Rosandra N. Kaplan; Rebecca D. Riba; Stergios Zacharoulis; Anna H. Bramley; Loïc Vincent; Carla Costa; Daniel D. MacDonald; David K. Jin; Koji Shido; Scott A. Kerns; et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 2005, 438, 820-827, 10.1038/nature04186.

- Hyunho Kim; Hyewon Chung; Jaehoon Kim; Dong‐Hee Choi; Yoojin Shin; Yong Guk Kang; Beop‐Min Kim; Sang‐Uk Seo; Seok Chung; Seung Hyeok Seok; et al. Macrophages‐Triggered Sequential Remodeling of Endothelium‐Interstitial Matrix to Form Pre‐Metastatic Niche in Microfluidic Tumor Microenvironment. Advanced Science 2019, 6, 1900195, 10.1002/advs.201900195.

- Christina E. Arnold; Peter Gordon; Robert N. Barker; Heather M. Wilson; The activation status of human macrophages presenting antigen determines the efficiency of Th17 responses. Immunobiology 2015, 220, 10-19, 10.1016/j.imbio.2014.09.022.

- Dorothée Duluc; Murielle Corvaisier; Simon Blanchard; Laurent Catala; Philippe Descamps; Erick Gamelin; Stéphane Ponsoda; Yves Delneste; Mohamed Hebbar; Pascale Jeannin; et al. Interferon-γ reverses the immunosuppressive and protumoral properties and prevents the generation of human tumor-associated macrophages. International Journal of Cancer 2009, 125, 367-373, 10.1002/ijc.24401.

- Khue G. Nguyen; Maura R. Vrabel; Siena M. Mantooth; Jared J. Hopkins; Ethan S. Wagner; Taylor A. Gabaldon; David A. Zaharoff; Localized Interleukin-12 for Cancer Immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 2020, 11, 575597, 10.3389/fimmu.2020.575597.

- Xiang Zheng; Kati Turkowski; Javier Mora; Bernhard Brüne; Werner Seeger; Andreas Weigert; Rajkumar Savai; Redirecting tumor-associated macrophages to become tumoricidal effectors as a novel strategy for cancer therapy. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 48436-48452, 10.18632/oncotarget.17061.