Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Toxicology

Mn-induced synaptic dysfunction, impaired neurotransmission is shown to be mediated by the effects of Mn on neurotransmitter systems and their complex interplay

- manganese

- neurotoxicity

- neuroinflammation

1. Introduction

Manganese (Mn) is an essential metal that is involved in a variety of physiological processes [1]. Mn naturally occurs in the Earth’s crust, predominantly as the 55Mn isotope, although a total of 18 isotopes have been described [2]. In biological systems, Mn exists in two oxidation states Mn2+ and Mn3+ that mediate redox cycling of Mn, which is involved in biological effects of the metal, including the Fenton reaction, transferrin-mediated transport, interference, as well as interference with other divalent metals (Mg2+, Fe2+), to name a few [3]. At the same time, in the environment Mn may exist in other positive (4+, 5+, and 6+) and even negative (3-) oxidation states. Due to its chemistry Mn exists in multiple inorganic and organic species. The most common inorganic species include oxides (dioxide, MnO2, and tetraoxide, Mn3O4), chloride (MnCl2), sulfate (MnSO4), manganese phosphate (MnPO4), carbonate (MnCO3), silicate (MnSiO3), etc. [4]. Among organic Mn species, methylcyclopentadienyl Mn tricarbonyl (MMT) as a gasoline additive, and Maneb and Mancozeb as pesticides/fungicides may be considered as significant health hazard due to high risk of overexposure [5]. In addition to anthropogenic sources of Mn into the environment, natural sources including soil erosion may also contribute to Mn emissions [4].

2. Neurotransmission

Recent studies have demonstrated a significant impact of Mn exposure in mice (25–100 μmol/kg i.p. for 24 days) on synaptic vesicle fusion through alteration of SNARE complex formation through calpain-dependent SNAP-25 cleavage [6]. It has been also demonstrated in SH-SY5Y cells exposed to 0–200 μM Mn for 0–24 h, that Mn-induced α-syn overexpression may also contribute to this mechanism [7]. In addition, Mn exposure (100 μM for 0–24 h) may be also responsible for down-regulation of SNAP-25 expression as well as impairment of SNARE-associated protein interaction in cultured neurons [8]. Impairment of synaptic vesicle fusion under Mn exposure (100 μM Mn for 24h) was shown to be mediated by the interference of α-syn accumulation with synaptotagmin/Rab3-GAP and Rab3A-GTP/Rab3-GAP signaling [9]. Taken together, these mechanisms may underlie Mn-induced alterations of neurotransmitter release. At the same time, recent studies have also unraveled the interference between Mn exposure and neurotransmitter metabolism [10].

2.1. Glutamate

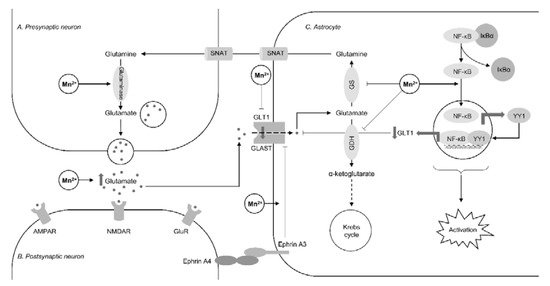

Regulation of glutamate transporters by Mn is considered as one of the key mechanisms of Mn impact on glutamatergic system [11] (Figure 1). Recent studies have confirmed earlier data and generated new data on Mn-dependent transcriptional epigenetics and translational regulation of glutamate transporters [12]. Mn exposure (30 mg/kg intranasal for 21 days) was shown to decrease EAAT1 (GLAST) and EAAT2 (GLT-1) promotor activities, as well as mRNA and protein levels resulting in reduced glutamate uptake in human astrocyte H4 cells as well as murine brain, being associated with neurobehavioral deficiency, reduced tyrosine hydroxylase mRNA and protein levels, as well as reduced histone H3 and H4 acetylation [13], all being reversed by valproic acid and sodium butyrate [14]. Our previous data from both in vitro (exposure to 250 μM Mn for 6 h) [15][16] and in vivo (exposure to 30 mg/kg intranasal for 21 days) [17] studies demonstrate that activation of Yin Yang 1 (YY1) transcription factor plays a significant role in GLAST and GLT-1 expression, whereas YY1 knockout significantly attenuated Mn-induced motor dysfunction, glutamate transporter reduction, tyrosine hydroxylase activity, as well as histone deacetylation [18]. At the same time, it has been demonstrated that a time- and dose-dependent increase in GLAST activity in chick cerebellar Bergmann glia cells in response to acute but non-toxic Mn exposure (200 µM for 30 min) may be associated with increased transporter affinity for [3H]-d-aspartate [19]. Using fluoxetine as an ephrin-A3 inhibitor it has been demonstrated that alterations in glutamate transporters and metabolism in Mn-exposed Kinming mice (50 mg/kg MnCl2 s.c. for two weeks) and cultured primary astrocytes (500 μM for 24 h) may be ephrin-A3-dependent [20].

Mn-induced decrease in GLAST and GLT-1 mRNA expression along with inhibition of glutamine synthetase and up-regulation of phosphate-activated glutaminase resulted in a significant increase of Glu and decline in Gln levels in hippocampus, thalamus, striatum, and globus pallidus of Mn-exposed (15 mg/kg i.p. for four weeks) rats [21]. However, an in vitro study using brain-derived mitochondrial fractions demonstrated that Mn is capable of inhibiting phosphate-activated glutaminase with IC50 = 2317 μM in a dose-dependent manner analogous to ammonia [22]. Inhibition of astrocytic glutamine synthetase in response to 100 µM exposure for 24 h may be mediated by microglial activation and its impact on astrocyte reactivity [23]. Another enzyme of glutamate catabolism, glutamate dehydrogenase, was found to be inhibited by Mn2+ exposure with the second isoenzyme (GDH2) showing greater sensitivity to metal-induced inhibition as compared to GDH1 [24].

Mn exposure (0–30 mg/kg i.p. for three weeks) resulted in a significant decrease of hippocampal mRNA and protein expression of NMDA receptor subunits (NR1, NR2A, and NR2B), as well as CREB and BDNF in newborn Sprague–Dawley rats [25].

Figure 1. The impact of manganese overexposure on glutamate-glutamine cycle. Manganese exposure results in a significant increase in glutamate levels through down-regulation of glutamine synthetase (GS) [21] and glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) [24] along with up-regulation of glutaminase [21]. These effects result in reduced glutamate-to-glutamine conversion as well as glutamate catabolism in Krebs cycle through the formation of α-ketoglutarate. Mn-induced inhibition of astrocyte glutamate uptake results from inhibition of glutamine transporters (GLT1 and GLAST). Recent studies demonstrated that this inhibitory effect may be mediated through NF-κB-dependent activation of Yin Yang 1 (YY1) transcription factor [15] and ephrin A3 [20]. It is also notable that Mn-induced NF-κB signaling also plays a significant role in astrocyte activation associated with reduced glutamine synthetase activity [23].

2.2. γ-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)

In welders, thalamic GABA levels were found to be associated with Mn deposition and the rate of Mn exposure, being the highest values observed at high exposure with air Mn levels of 0.23 ± 0.18 mg/m3 [26]. Specifically, thalamic GABA levels in welders significantly correlated with air Mn concentrations and cumulative exposure for the last three and 12 months [27]. However, another study did not observe any association between thalamic and striatal GABA levels and blood Mn or airborne metal exposure levels in welders [28]. This inconsistency may be explained by non-linear association between Mn exposure and brain GABA alterations, with the latter being undetectable at lower doses and periods of exposure [29].

Serum GABA levels were found to be reduced in association with circulating Gln and thyroid hormone levels in response to subacute Mn exposure (7.5–30 mg/kg i.p. five days/week for four weeks) in rats [30]. Another study demonstrated that Mn exposure (6.55 mg/kg Mn i.p. five days/week for 12 weeks) significantly decreased basal ganglia GABA levels, glutamate-to-GABA ratio, as well as affected GAD and GABA-T activity, and GAT-1 and GABAA mRNA expression in rats [31][32]. Reduced hypothalamic GABAA receptor subunits protein expression in response to Mn exposure (2.5–10 mg/kg oral for 11 days) was associated with increasing NO production through amelioration of inhibitory effect of GABA on NO synthase, altogether leading to aberrant gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) production [33].

2.3. Dopamine

Manganese is known to interfere with dopamine signaling being the leading pathogenetic mechanism of Parkinson’s disease [34]. Dopaminergic neurons are considered as one of the main targets for Mn toxicity with predominant accumulation of the metal in substantia nigra pars reticulata and pars compacta and its localization adjacent to the nucleus [35]. In turn, Mn-induced dopaminergic neuron loss associated with motor activity deficits in rats intraperitoneally injected with Mn (1–5 mg/kg every 10 days for 150 days) [36]. At the same time, our earlier study in C. elegans demonstrated that Mn exposure (15–45 mM for 4 h) resulted in a significant decline in dopamine levels without loss of dopaminergic neurons [37]. A study using Mn-exposed (5–6.7 mg/kg Mn for 25–80 weeks) non-human primates demonstrated a significant decrease in dopamine release in the frontal cortex in 4 of 6 animals [38].

Interference between dopamine signaling and Mn may be mediated by its influence on tyrosine hydroxylase. Specifically, Mn exposure (10 mg/kg/day i.g. for 30 days) intensified striatal dopamine and nigral tyrosine hydroxylase loss in MitoPark mouse. These alterations were also associated with Mn-induced mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, microglia activation and neuroinflammation, as well as PD-associated protein oligomerization [39].

However, the impact of Mn exposure on tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine metabolism was found to be not similar through a lifespan. Specifically, shortly after early-life Mn exposure (5–20 mg/kg i.p. for four days) in rats a significant increase in striatal TH protein levels and TH phosphorylation at Ser19, Ser31, and Ser40 was observed. At the same time, in adulthood TH levels were found to be reduced in a dose-dependent manner in association with increased phosphorylation at Ser19 and Ser40 [40]. Nearly similar age-dependent effect on TH activity was observed in zebrafish larvae exposed to 0.1–0.5 mM for five days [41].

Certain studies have highlighted the mechanisms of transcriptional regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase under Mn exposure. Transcription factor RE1-silencing transcription factor (REST) was shown to overwhelm Mn-induced alterations in TH activity through up-regulation of mRNA and protein transcription in dopaminergic neuronal cells, as well as ameliorated other toxic effects of Mn exposure (250 μM for 12 h) including apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress [42]. Kumasaka et al. (2017) demonstrated that a decline TH expression in TGW cells may be mediated by Mn (30–100 μM for 24 h) exposure-induced down-regulation of mRNA and protein transcription, as well as increased degradation of c-RET kinase [43][44].

In addition, in vivo Mn exposure (0–50 mg/kg i.p. for 2 weeks) was shown to cause reduction in striatal dopamine D1 receptor and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits (NR1 and NR2) mRNA and protein expression, as well as inhibition of DR1 and NMDAR interaction, being associated with altered spatial learning and memory in mice [45]. Examination of workers with clinical parkinsonism exposed to 2.6 mg Mn/m3-years revealed increased nigral D2R non-displaceable binding potential, being also associated with duration of occupational Mn exposure and motor dysfunction [46].

2.4. Catecholamines

Catecholaminergic neurotransmission was also found to be affected by Mn exposure. In parallel with markers of dopaminergic dysfunction, Mn exposure in rats (0–50 mg/kg i.g. for 21–100 days) resulted in a significant decrease in norepinephrine levels, evoked norepinephrine release, resulting in medial prefrontal cortex catecholaminergic dysfunction and being associated with impaired attention, motor dysfunction, and altered impulse control [47]. Reversal of Mn-induced alterations of motor functions with methylphenidate treatment in Mn-exposed (0–50 mg/kg i.g. for 145 days) rats underlines the role of prefrontal cortex and striatal catecholaminergic dysfunction in Mn-associated motor impairment [48]. Correspondingly, although Mn exposure (0–50 mg/kg i.g. for 21–500 days) resulted in a significant reduction of potassium-stimulated extracellular norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin levels, as well as striatal dopamine levels, the observed alterations of attention and fine motor function are indicative of the role of Mn-induced catecholaminergic dysfunction in neurobehavioral disorders [49].

2.5. Acetylcholine

Mn exposure (25–300 for 24 h and 14 days) was shown to disrupt cholinergic neurotransmission in basal forebrain cholinergic neurons through up-regulation of AChE mRNA expression and protein activity in parallel with inhibition of cholineacetyltransferase activity and down-regulation of high-affinity choline transporter mRNA, as well as cholinergic neuron death, altogether resulting in reduced acetylcholine levels [50].

The observed increase in hypothalamic, cerebral, and cerebellar AChE activity in Mn-treated (15 mg/kg i.g. for 45 days) rats was also associated with increased ROS production and depletion of the antioxidant system in these brain regions, as well as locomotor and motor deficits [51]. These findings are in agreement with the observation of Mn (30 mg/kg Mn p.o. for 35 days) exposure-induced increase in striatal and hippocampal acetylcholinesterase activity in rats and its reversal by rutin treatment [52].

Mn exposure (10–50 mM for 30 min) during L1 larval stage in C. elegans also resulted in a significant increase in AChE mRNA expression as well as dose-dependent cholinergic neurodegeneration, both being aggravated when co-exposed to Mn and methylmercury (MeHg) [53].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22094646

References

- Pfalzer, A.C.; Bowman, A.B. Relationships between Essential Manganese Biology and Manganese Toxicity in Neurological Disease. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2017, 4, 223–228.

- Chen, P.; Bornhorst, J.; Aschner, M. Manganese metabolism in humans. Front. Biosci. 2018, 23, 1655–1679.

- Aguirre, J.D.; Culotta, V.C. Battles with iron: Manganese in oxidative stress protection. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 13541–13548.

- Martinez-Finley, E.J.; Chakraborty, S.; Aschner, M. Manganese in Biological Systems. Encyclopedia of Metalloproteins; Kretsinger, R.H., Uversky, V.N., Permyakov, E.A., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 1297–1303.

- Michalke, B.; Fernsebner, K. New insights into manganese toxicity and speciation. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2014, 28, 106–116.

- Wang, C.; Xu, B.; Ma, Z.; Liu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z.F. Inhibition of Calpains Protects Mn-Induced Neurotransmitter release disorders in Synaptosomes from Mice: Involvement of SNARE Complex and Synaptic Vesicle Fusion. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 3701.

- Wang, C.; Ma, Z.; Yan, D.Y.; Liu, C.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z.F.; Xu, B. Alpha-Synuclein and Calpains Disrupt SNARE-Mediated Synaptic Vesicle Fusion During Manganese Exposure in SH-SY5Y Cells. Cells 2018, 7, 258.

- Wang, C.; Xu, B.; Song, Q.F.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z.F. Manganese exposure disrupts SNARE protein complex-mediated vesicle fusion in primary cultured neurons. Environ. Toxicol. 2017, 32, 705–716.

- Wang, T.Y.; Ma, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.; Yan, D.Y.; Deng, Y.; Liu, W.; Xu, Z.F.; Xu, B. Manganese-induced alpha-synuclein overexpression impairs synaptic vesicle fusion by disrupting the Rab3 cycle in primary cultured neurons. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 285, 34–42.

- Soares, A.; Silva, A.C.; Tinkov, A.A.; Khan, H.; Santamaría, A.; Skalnaya, M.G.; Skalny, A.V.; Tsatsakis, A.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M.; et al. The impact of manganese on neurotransmitter systems. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 61, 126554.

- Lee, E.; Karki, P.; Johnson, J., Jr.; Hong, P.; Aschner, M. Manganese Control of Glutamate Transporters’ Gene Expression. Adv. Neurobiol. 2017, 16, 1–12.

- Karki, P.; Smith, K.; Johnson, J., Jr.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E.Y. Genetic dys-regulation of astrocytic glutamate transporter EAAT2 and its implications in neurological disorders and manganese toxicity. Neurochem. Res. 2015, 40, 380–388.

- Johnson, J., Jr.; Pajarillo, E.; Karki, P.; Kim, J.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Valproic acid attenuates manganese-induced reduction in expression of GLT-1 and GLAST with concomitant changes in murine dopaminergic neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2018, 67, 112–120.

- Johnson, J., Jr.; Pajarillo, E.A.B.; Taka, E.; Reams, R.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Valproate and sodium butyrate attenuate manganese-decreased locomotor activity and astrocytic glutamate transporters expression in mice. Neurotoxicology 2018, 64, 230–239.

- Karki, P.; Kim, C.; Smith, K.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Transcriptional Regulation of the Astrocytic Excitatory Amino Acid Transporter 1 (EAAT1) via NF-κB and Yin Yang 1 (YY1). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 23725–23737.

- Karki, P.; Webb, A.; Smith, K.; Johnson, J.J.; Lee, K.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Yin Yang 1 is a repressor of glutamate transporter EAAT2, and it mediates manganese-induced decrease of EAAT2 expression in astrocytes. Mol. Cell Biol. 2014, 34, 1280–1289.

- Pajarillo, E.; Johnson, J., Jr.; Rizor, A.; Nyarko-Danquah, I.; Adinew, G.; Bornhorst, J.; Stiboller, M.; Schwerdtle, T.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; et al. Astrocyte-specific deletion of the transcription factor Yin Yang 1 in murine substantia nigra mitigates manganese-induced dopaminergic neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 15662–15676.

- Karki, P.; Smith, K.; Johnson, J., Jr.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. Role of transcription factor yin yang 1 in manganese-induced reduction of astrocytic glutamate transporters: Putative mechanism for manganese-induced neurotoxicity. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 88, 53–59.

- Escalante, M.; Soto-Verdugo, J.; Hernández-Kelly, L.C.; Hernández-Melchor, D.; López-Bayghen, E.; Olivares-Bañuelos, T.N.; Ortega, A. GLAST Activity is Modified by Acute Manganese Exposure in Bergmann Glial Cells. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1365–1374.

- Qi, Z.; Yang, X.; Sang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, B.; Liu, W.; He, M.; Xu, Z.; Deng, Y.; et al. Fluoxetine and Riluzole Mitigates Manganese-Induced Disruption of Glutamate Transporters and Excitotoxicity via Ephrin-A3/GLAST-GLT-1/Glu Signaling Pathway in Striatum of Mice. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 38, 508–523.

- Li, Z.C.; Wang, F.; Li, S.J.; Zhao, L.; Li, J.Y.; Deng, Y.; Zhu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.W.; Peng, D.J.; Jiang, Y.M. Sodium Para-aminosalicylic Acid Reverses Changes of Glutamate Turnover in Manganese-Exposed Rats. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2020, 197, 554.

- Rivera-Mancía, S.; Tristán-López, L.; Hernández-Díaz, K.; Rivera-Espinosa, L.; Ríos, C.; Montes, S. In vitro inhibition of brain phosphate-activated glutaminase by ammonia and manganese. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2020, 62, 126625.

- Guan, R.; Wang, T.; Chen, J.; Luo, W.; Liu, M. The activation of microglia caused by lead and manganese co-exposure induces activation of astrocytes and decrease of glutamine synthetase activity. Xi Bao Yu Fen Zi Mian Yi Xue Za Zhi 2016, 32, 313–318.

- Dimovasili, C.; Aschner, M.; Plaitakis, A.; Zaganas, I. Differential interaction of hGDH1 and hGDH2 with manganese: Implications for metabolism and toxicity. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 88, 60–65.

- Wang, L.; Fu, H.; Liu, B.; Liu, X.; Chen, W.; Yu, X. The effect of postnatal manganese exposure on the NMDA receptor signaling pathway in rat hippocampus. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2017, 31, 12.

- Ma, R.E.; Ward, E.J.; Yeh, C.L.; Snyder, S.; Long, Z.; Gokalp Yavuz, F.; Zauber, S.E.; Dydak, U. Thalamic GABA levels and occupational manganese neurotoxicity: Association with exposure levels and brain MRI. Neurotoxicology 2018, 64, 30–42.

- Edmondson, D.A.; Ma, R.E.; Yeh, C.L.; Ward, E.; Snyder, S.; Azizi, E.; Zauber, S.E.; Wells, E.M.; Dydak, U. Reversibility of neuroimaging markers influenced by lifetime occupational manganese exposure. Toxicol. Sci. 2019, 172, 181–190.

- Casjens, S.; Dydak, U.; Dharmadhikari, S.; Lotz, A.; Lehnert, M.; Quetscher, C.; Stewig, C.; Glaubitz, B.; Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Edmondson, D.; et al. Association of exposure to manganese and iron with striatal and thalamic GABA and other neurometabolites—Neuroimaging results from the WELDOX II study. Neurotoxicology 2018, 64, 60–67.

- Edmondson, D.A.; Yeh, C.L.; Hélie, S.; Dydak, U. Whole-brain R1 predicts manganese exposure and biological effects in welders. Arch. Toxicol. 2020, 94, 3409–3420.

- Ou, C.Y.; He, Y.H.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L.; Shi, W.X.; Li, S.J. Effects of Sub-Acute Manganese Exposure on Thyroid Hormone and Glutamine (Gln)/Glutamate (Glu)-γ- Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) Cycle in Serum of Rats. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2157.

- Li, S.J.; Ou, C.Y.; He, S.N.; Huang, X.W.; Luo, H.L.; Meng, H.Y.; Lu, G.D.; Jiang, Y.M.; Vieira Peres, T.; Luo, Y.N.; et al. Sodium p-Aminosalicylic Acid Reverses Sub-Chronic Manganese-Induced Impairments of Spatial Learning and Memory Abilities in Rats, but Fails to Restore γ-Aminobutyric Acid Levels. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 400.

- Ou, C.Y.; Luo, Y.N.; He, S.N.; Deng, X.F.; Luo, H.L.; Yuan, Z.X.; Meng, H.Y.; Mo, Y.H.; Li, S.J.; Jiang, Y.M. Sodium P-Aminosalicylic Acid Improved Manganese-Induced Learning and Memory Dysfunction via Restoring the Ultrastructural Alterations and γ-Aminobutyric Acid Metabolism Imbalance in the Basal Ganglia. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2017, 176, 143–153.

- Yang, X.; Tan, J.; Xu, X.; Yang, H.; Wu, F.; Xu, B.; Liu, W.; Shi, P.; Xu, Z.; Deng, Y. Prepubertal overexposure to manganese induce precocious puberty through GABAA receptor/nitric oxide pathway in immature female rats. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2020, 188, 109898.

- Aschner, M.; Erikson, K.M.; Herrero Hernández, E.; Tjalkens, R. Manganese and its role in Parkinson’s disease: From transport to neuropathology. Neuromol. Med. 2009, 11, 252–266.

- Robison, G.; Sullivan, B.; Cannon, J.R.; Pushkar, Y. Identification of dopaminergic neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta as a target of manganese accumulation. Metallomics 2015, 7, 748–755.

- Fan, X.M.; Luo, Y.; Cao, Y.M.; Xiong, T.W.; Song, S.; Liu, J.; Fan, Q.Y. Chronic Manganese Administration with Longer Intervals Between Injections Produced Neurotoxicity and Hepatotoxicity in Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 1941–1952.

- Gubert, P.; Puntel, B.; Lehmen, T.; Fessel, J.P.; Cheng, P.; Bornhorst, J.; Trindade, L.S.; Avila, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Soares, F.A.A. Metabolic effects of manganese in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans through DAergic pathway and transcription factors activation. Neurotoxicology 2018, 67, 65–72.

- Guilarte, T.R.; Yeh, C.L.; McGlothan, J.L.; Perez, J.; Finley, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wong, D.F.; Dydak, U.; Schneider, J.S. PET imaging of dopamine release in the frontal cortex of manganese-exposed non-human primates. J. Neurochem. 2019, 150, 188–201.

- Langley, M.R.; Ghaisas, S.; Ay, M.; Luo, J.; Palanisamy, B.N.; Jin, H.; Anantharam, V.; Kanthasamy, A.; Kanthasamy, A.G. Manganese exposure exacerbates progressive motor deficits and neurodegeneration in the MitoPark mouse model of Parkinson’s disease: Relevance to gene and environment interactions in metal neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicology 2018, 64, 240–255.

- Peres, T.V.; Ong, L.K.; Costa, A.P.; Eyng, H.; Venske, D.K.; Colle, D.; Gonçalves, F.M.; Lopes, M.W.; Farina, M.; Aschner, M.; et al. Tyrosine hydroxylase regulation in adult rat striatum following short-term neonatal exposure to manganese. Metallomics 2016, 8, 597–604.

- Altenhofen, S.; Wiprich, M.T.; Nery, L.R.; Leite, C.E.; Vianna, M.R.M.R.; Bonan, C.D. Manganese(II) chloride alters behavioral and neurochemical parameters in larvae and adult zebrafish. Aquat. Toxicol. 2017, 182, 172–183.

- Porte Alcon, S.; Gorojod, R.M.; Kotler, M.L. Kinetic and protective role of autophagy in manganese-exposed BV-2 cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2020, 1867, 118787.

- Pajarillo, E.; Rizor, A.; Son, D.S.; Aschner, M.; Lee, E. The transcription factor REST up-regulates tyrosine hydroxylase and antiapoptotic genes and protects dopaminergic neurons against manganese toxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 3040–3054.

- Kumasaka, M.Y.; Yajima, I.; Ohgami, N.; Ninomiya, H.; Iida, M.; Li, X.; Oshino, R.; Tanihata, H.; Yoshinaga, M.; Kato, M. Manganese-Mediated Decrease in Levels of c-RET and Tyrosine Hydroxylase Expression In Vitro. Neurotox. Res. 2017, 4, 661–670.

- Song, Q.; Deng, Y.; Yang, X.; Bai, Y.; Xu, B.; Liu, W.; Zheng, W.; Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Xu, Z. Manganese-Disrupted Interaction of Dopamine D1 and NMDAR in the Striatum to Injury Learning and Memory Ability of Mice. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 53, 6745–6758.

- Criswell, S.R.; Warden, M.N.; Searles Nielsen, S.; Perlmutter, J.S.; Moerlein, S.M.; Sheppard, L.; Lenox-Krug, J.; Checkoway, H.; Racette, B.A. Selective D2 receptor PET in manganese-exposed workers. Neurology 2018, 91, 1022–1030.

- Conley, T.E.; Beaudin, S.A.; Lasley, S.M.; Fornal, C.A.; Hartman, J.; Uribe, W.; Khan, T.; Strupp, B.J.; Smith, D.R. Early postnatal manganese exposure causes arousal dysregulation and lasting hypofunctioning of the prefrontal cortex catecholaminergic systems. J. Neurochem. 2020, 153, 631–649.

- Beaudin, S.A.; Strupp, B.J.; Lasley, S.M.; Fornal, C.A.; Mandal, S.; Smith, D.R. Oral methylphenidate alleviates the fine motor dysfunction caused by chronic postnatal manganese exposure in adult rats. Toxicol. Sci. 2015, 144, 318–327.

- Lasley, S.M.; Fornal, C.A.; Mandal, S.; Strupp, B.J.; Beaudin, S.A.; Smith, D.R. Early Postnatal Manganese Exposure Reduces Rat Cortical and Striatal Biogenic Amine Activity in Adulthood. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 173, 144–155.

- Moyano, P.; García, J.M.; Anadon, M.J.; Lobo, M.; García, J.; Frejo, M.T.; Sola, E.; Pelayo, A.; Pino, J.D. Manganese induced ROS and AChE variants alteration leads to SN56 basal forebrain cholinergic neuronal loss after acute and long-term treatment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 583–594.

- Adedara, I.A.; Ego, V.C.; Subair, T.I.; Oyediran, O.; Farombi, E.O. Quercetin Improves Neurobehavioral Performance Through Restoration of Brain Antioxidant Status and Acetylcholinesterase Activity in Manganese-Treated Rats. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 42, 1219–1229.

- Nkpaa, K.W.; Onyeso, G.I.; Kponee, K.Z. Rutin abrogates manganese-Induced striatal and hippocampal toxicity via inhibition of iron depletion, oxidative stress, inflammation and suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2019, 53, 8–15.

- Schetinger, M.R.C.; Peres, T.V.; Arantes, L.P.; Carvalho, F.; Dressler, V.; Heidrich, G.; Bowman, A.B.; Aschner, M. Combined exposure to methylmercury and manganese during L1 larval stage causes motor dysfunction, cholinergic and monoaminergic up-regulation and oxidative stress in L4 Caenorhabditis elegans. Toxicology 2019, 411, 154–162.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!