The present review mainly focuses on the anticancer efficacies, mechanisms of action and chemical structures of 236 cyclopeptides with natural origins. Additionally, studies of the structure–activity relationship, total synthetic strategies as well as bioactivities of natural cyclopeptides are also included in this article. Herein, we provide an overview of anticancer cyclopeptides that were discovered in the past 20 years. Full contents of the review report can be found in International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(8), 3973; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22083973.

- cyclopeptides

- anticancer

- natural products

1. Introduction

Cancer has become an enormous burden in society and a leading cause of death in the world. Apart from aging, the risk factors of modern daily life such as smoking, unhealthy diet and mental stress also play significant roles in the growing incidence of cancer [1]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 10 million of people were killed by cancer in 2020. New cancer cases reached to 18 million in 2018, and are expected to grow to up to 27.5 million in 2040 [2,3]. Conventional therapeutic approaches for the treatment of cancer include chemotherapy, radiotherapy and surgical resection. In recent years, advancement in cancer treatment has been applied with some novel therapies and choices for patients to improve their survival chances, such as immunotherapy, targeted therapy, hormone therapy, stem cell transplant and precision medicine [4]. However, low specificity to cancer cells, high toxicities to normal tissues as well as drug resistance are often the most problematic concerns [5,6,7]. Therefore, studies on the development of new drugs and therapies for cancer with higher efficacy are urgent and crucial.

From ancient times, taking Chinese Medicine as an example, people have been familiar with medicinal properties of natural resources and the benefits of using them to treat diseases [8]. Hence, due to their extraordinary chemical diversity with different origins, natural products are of great potential to be developed as new drugs for cancer prevention and treatment [9]. Natural cyclopeptides, due to their special chemical properties and therapeutic potency have attracted great attention from both academic researchers and pharmaceutical companies in recent years.

Cyclopeptides, also known as cyclic peptides, are polypeptides formed from amino acids arranged in a cyclic ring structure [10]. Most natural cyclopeptides are found to be assembled with 4–10 amino acids. However, some natural cyclopeptides can contain dozens of amino acids [11,12,13,14]. In the past 20 years, hundreds of ribosomally synthesized cyclopeptides have been isolated from a variety of living creatures with various biological activities. In fact, there are two biosynthetic mechanisms of cyclopeptides—ribosomal and non-ribosomal pathways. The ribosomal pathway merely requires the 21 basic proteinogenic amino acids for the synthesis of cyclopeptides, whereas the non-ribosomal pathway depends on non-ribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs) in incorporating functional groups, such as hydroxyl and N-methyl groups, to the existing peptides [15,16]. A large number of cyclopeptides have been isolated and demonstrated to deliver a wide spectrum of bioactivities. Very often, they can be served as antibiotics (e.g., microcin 25 from Escherichia coli) [17], protease inhibitors (e.g., SFTI-1 from Helianthus annuus) [18], boosting agents for the innate immune system (e.g., θ-defensins from Macaca mulatta) [19], anticancer agents (e.g., chlamydocin from Diheterospora chlamydosporia) [20] and so on. According to previous reports, cyclization is an important process for peptide stabilization [21]. Compared with linear peptides, cyclic peptides may have a better biological potency due to the rigidity of their conformation [22]. Moreover, the rigidity of cyclopeptides may also increase the binding affinity to their target molecules, allowing enhanced receptor selectivity as rigid structures often decrease the interaction entropy to a negative Gibbs free energy. Furthermore, cyclopeptides are resistant to exopeptidases because they contain no amino/carbonyl termini in their skeletons, so that they exert more stable binding capability than linear peptides do. Owing to the absence of the amino/carbonyl termini, the less flexible backbone of cyclopeptides even enhances their resistance to endopeptidases, and therefore, cyclopeptides are considered as useful biochemical tools with high specificity [23]. In particular, when serving as an anticancer agent, the cyclic structure of the peptide eliminates the effect of charged termini and thus increases membrane permeability [24]. As a result, cyclopeptides can penetrate to the tumors without much hurdle while exhibiting their anti-proliferative effect [25].

Overall, the structural rigidity, biochemical stability, binding affinity and membrane permeability are the predominant advantages of cyclopeptides in comparison of linear peptides and other chemicals for therapeutic purposes [10]. Owing to these exceptional characteristics, natural cyclopeptides are considered as promising lead compounds for the development of novel anticancer drugs. With the efforts from researchers around the world, a great number of cyclopeptides with anticancer effects have been identified from various living entities.

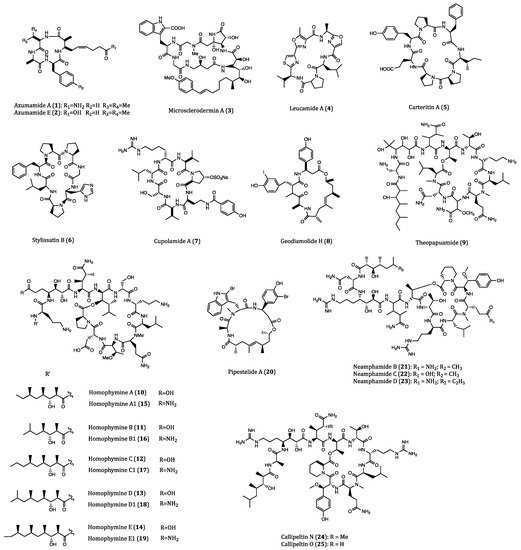

2. Marine-Derived Anticancer Cyclopeptides

2.1. Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Sponge

2.2. Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Ascidians/Tunicates

2.3. Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Mollusks

2.4. Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Marine Algae

| Name | Biological Source | Anticancer Activity | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Sponge | |||

| Azumamide A (1) | Mycale izuensis | HDAC inhibitory activity against K562 cells (IC50 = 0.045 μM); Cytostatic effects on WiDr (IC50 = 5.8 μM) and K562 (IC50 = 4.5 μM) cells | [35,36,37,38,39] |

| Azumamide E (2) | Mycale izuensis | HDAC inhibitory activity against K562 cells (IC50 = 0.045 μM) | [35,36,37,38,39] |

| Microsclerodermin A (3) | Microscleroderma herdmani | Induction of apoptosis in AsPC-1 (IC50 = 2.3 µM), BxPC-3 (IC50 = 0.8 µM) and PANC-1 (IC50 = 4.0 µM) cells. | [40,41,42] |

| Leucamide A (4) | Leucetta microraphis | Inhibitory activities to HM02 (GI50 = 8.5 µM), HepG2 (GI50 = 9.7 µM) and Huh7 (GI50 = 8.3 µM) cells. | [43,44] |

| Carteritin A (5) | Sponge, Stylissa carteri | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 1.3 µM), RAW264 (IC50 = 1.5 µM) and HeLa (IC50 = 0.7 µM) cells | [45] |

| Stylissatin B (6) | Stylissa massa | Inhibitory effects on HCT116, HepG2, BGC823, NCI-H1650, A2780 and MCF7 cells. (IC50 = 2.3 to 10.6 µM) | [46] |

| Cupolamide A (7) | Theonella cupola | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 7.5 µM) cell. | [47] |

| Geodiamolide H (8) | Geodia corticostylifera | Anti-proliferative activitiy against T47D (EC50 = 38.36 nM) and MCF7 (EC50 = 89.96 nM) cells | [48,49,50] |

| Theopapuamide (9) | Theonella swinhoei | Cytotoxicity against CEM-TART (EC50 = 0.5 µM) and HCT116 (EC50 = 0.9 µM) cells. | [51] |

| Homophymines A-E (10–14) & A1-E1 (15–19) | Homophymia sp. | Anti-proliferative against several cancer cell lines (IC50 = 2 to 100 nM), among which PC3 and OV3 are the most sensitive. | [52,53] |

| Pipestelide A (20) | Pipestela candelabra | Cytotoxicity against KB (IC50 = 0.1 µM) cell. | [54] |

| Neamphamides B-D (21–23) | Neamphius huxleyi | Cytotoxicity against A549, LNCaP and PC3 cells. (IC50 = 91 to 230 nM) | [55,56] |

| Callipeltins N (24) and O (25) | Asteropus sp. | Cytotoxicity against A2058, HT29, MCF7 and MRC-5 cells. (IC50 = 0.16 to 0.21 µM and 0.48 to 2.08 µM, respectively) | [57] |

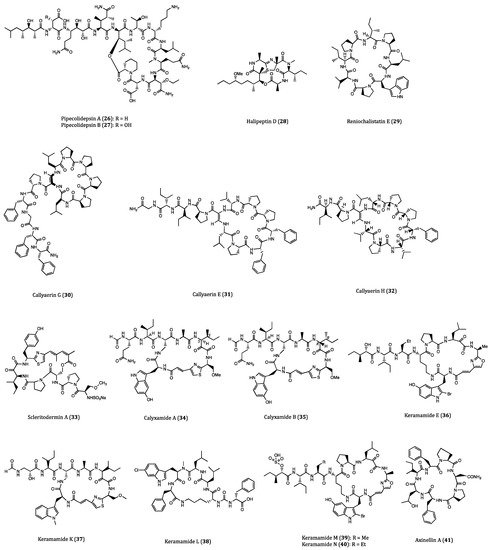

| Pipecolidepsins A (26) and B (27) | Homophymia lamellosa | Cytotoxicity against A549 (GI50 = 0.6 and 0.04 µM, respectively), HT29 (GI50 = 1.12 and 0.01 µM, respectively) and MDA-MB-231 (GI50 = 0.7 and 0.02 µM, respectively) cells. | [58,59,60,61] |

| Halipeptin D (28) | Leiosella cf. arenifibrosa | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 cell line (IC50 = 7 nM) and BMS ODCP with an average IC50 value of 420 nM. | [62,63] |

| Reniochalistatin E (29) | Reniochalina stalagmitis | Cytotoxicity against RPMI-8226 (IC50 = 4.9 μM) and MGC-803 (IC50 = 9.7 μM) cells. | [64,65] |

| Callyaerin G (30) | Callyspngia aerizusa | Cytotoxicity against L5178Y (ED50 = 4.1 mM) and HeLa (ED50 = 41.8 mM) cells. | [66] |

| Callyaerins E (31) and H (32) | Callyspngia aerizusa | Cytotoxicity against L5178Y (ED50 = 0.39 and 0.48 μM, respectively). | [67] |

| Scleritodermin A (33) | Scleritoderma nodosum | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 1.9 μM), HCT116/VM46 (IC50 = 5.6 μM), A2780 (IC50 = 0.94 μM) and SKBR3 (IC50 = 0.67 μM) cells. | [68,69,70] |

| Calyxamides A (34) and B (35) | Discodermia calyx | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 3.9 and 0.9 μM, respectively) cell. | [71] |

| Keramamide E (36) | Theonella sp. | Cytotoxicity against L1210 (IC50 = 1.42 µM) and KB (IC50 = 1.38 µM) cells. | [72] |

| Keramamides K (37) and L (38) | Theonella sp. | Cytotoxicity against L1210 (IC50 = 0.77 and 0.5 µM, respectively) and KB (IC50 = 0.45 and 0.97 µM, respectively) cells. | [73] |

| Keramamides M (39) and N (40) | Theonella sp. | Cytotoxicity against L1210 (IC50 = 2.02 and 2.33 µM, respectively) and KB (IC50 = 5.05 and 6.23 µM, respectively) cells. | [74,75] |

| Axinellins A (41) and B (42) | Axinella carteri | Cytotoxicity against NSLC-N6 (IC50 = 16.7 and 29.8 µM, respectively) cell. | [76,77] |

| Stylopeptide 2 (43) | Stylotella sp. | Inhibition of 23% BT-549 cell growth and 44% Hs578T cell growth at one dose (10−5 M). | [78] |

| Stylissamide X (44) | Stylissa sp. | Anti-migration effects on HeLa cell. | [79,80] |

| Aciculitins A-C (45–47) | Aciculites orientalis | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 0.37 µM) cell. | [81] |

| Nazumazoles A-C (48–50) | Theonella swinhoei | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 0.83 µM) cell. | [82] |

| Theonellamide G (51) | Theonella swinhoei | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 6.0 µM) cell. | [83] |

| Koshikamide B (52) | Theonella sp. | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 3.62 µM) and P388 (IC50 = 0.22 µM) cells. | [84] |

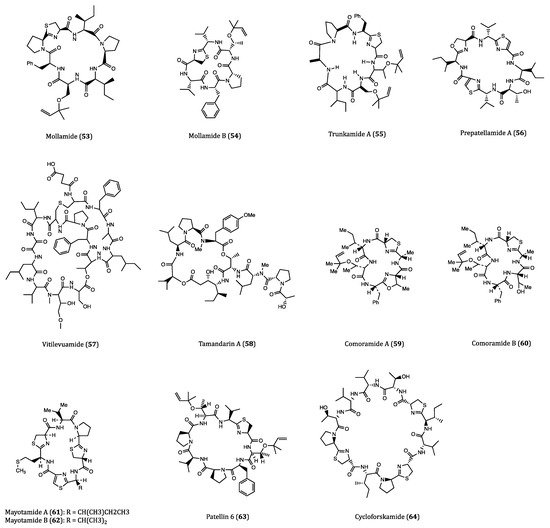

| Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Ascidians/Tunicates | |||

| Mollamide (53) | Ascidian, Didemnum molle | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 1.24 µM), A549 (IC50 = 3.1 µM), HT29 (IC50 = 3.1 µM) and CV1 (IC50 = 3.1 µM) cells. | [87,88] |

| Mollamide B (54) | Tunicate, Didemnum molle | Growth inhibition of H460, MCF7 and SF-268 cells. | [89] |

| Trunkamide A (55) | Ascidian, Lissoclinum sp. | Cytotoxicity against A549, P388, HT29 and MEL28 cells. (IC50 = 0.6 to 1.19 µM) | [90,91] |

| Prepatellamide A (56) | Ascidian, Lissoclinum patella | Cytotoxicity against P388 cells. (IC50~6.57 µM) | [92] |

| Vitilevuamide (57) | Ascidian, Didemnum cuculiferum | Cytotoxicity against HCT116 (IC50 = 6.24 nM), A549 (IC50 = 0.12 µM), SKMEL-5 (IC50 = 0.31 µM) and A498 (IC50 = 3.12 µM) cells. | [93,94] |

| Tamandarin A (58) | Ascidian, Didemnidae sp. | Cytotoxicity against BX-PC3 (IC50 = 1.69 nM), DU145 (IC50 = 1.29 nM), UM-SCC-10B (IC50 = 0.94 nM) cells. | [95,96,97] |

| Comoramides A-B (59–60) & Mayotamides A-B (61–62) | Ascidian, Didemnum molle | Cytotoxicity against A549, HT29 and MEL28 cells. (IC50 = 7.22 to 14.97 µM) | [98] |

| Patellin 6 (63) | Ascidian, Lissoclinum patella | Cytotoxicity against P388, A549, HT29 and CV1 cells. (IC50~2.08 µM) | [99] |

| Cycloforskamide (64) | Sea slug, Pleurobranchus forskalii | Cytotoxicity against P388 cell (IC50 = 5.8 µM). | [100] |

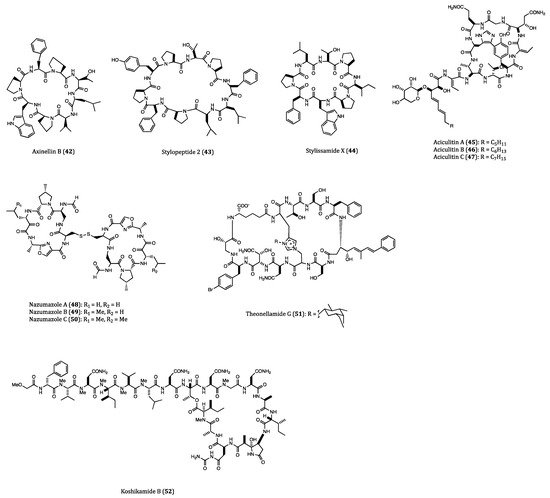

| Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Mollusks | |||

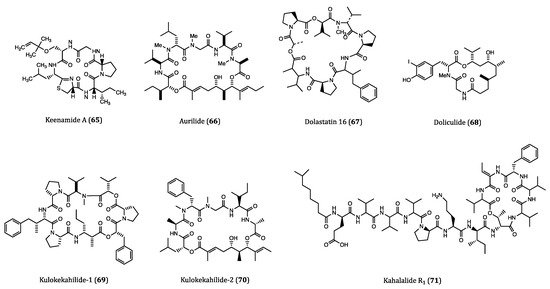

| Keenamide A (65) | Mollusk, Pleurobranchus forskali | Anti-proliferative activity against A549, P388, MEL20 and HT29 cells. (IC50 = 4.03 to 8.05 µM) | [103] |

| Aurilide (66) | Sea hare, Dolabella auricularia | Cytotoxicity against HeLa S3 (IC50 = 0.013 µM) cell. Inhibitory activity against ovarian, renal and prostate cancer cells in NCI 60 cell lines. | [104,105] |

| Dolastatin 16 (67) | Sea hare, Dolabella auricularia | Cytotoxicity against H460 (GI50 = 1.09 nM), KM20L2 (GI50 = 1.37 nM), SF-295 (GI50 = 5.92 nM) and SKMEL-5 (GI50 = 3.75 nM) cells. Anti-proliferative effects against 5 human leukemia cell lines | [106] |

| Doliculide (68) | Sea hare, Dolabella auricularia | Cytotoxicity against HeLa S3 (IC50 = 1.62 nM) cell. | [107,108,109,110] |

| Kulokekahilide-1 (69) | Mollusk, Philinopsis speciosa | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 2.2 µM) cell. | [111] |

| Kulokekahilide-2 (70) | Mollusk, Philinopsis speciosa | Cytotoxicity against P388 (IC50 = 4.2 nM), SK-OV-3 (IC50 = 7.5 nM), MDA-MB-435 (IC50 = 14.6 nM) and A-10 (IC50 = 59.1 nM) cells. | [112,113,114] |

| Kahalalide R1 (71) | Sea slug, Elysia grandifolia | Cytotoxicity against MCF7 (IC50 = 0.14 µM), L1578Y (IC50 = 4.26 nM) cells. | [117] |

| Anticancer Cyclopeptides Derived from Marine Algae | |||

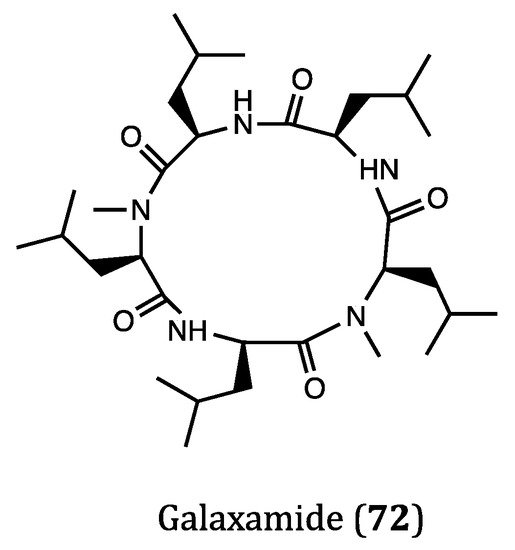

| Galaxamide (72) | Algae, Galaxaura filamentosa | Inhibitory activity against GRC-1 (IC50 = 7.18 μM) and HepG2 (IC50 = 7.81 μM) cells. | [119,120] |

3. Terrestrial Plant-Derived Anticancer Cyclopeptides

Plants are undeniably an important source for natural products. Nowadays, traditional plant-based medicines are still prevalently used for healthcare and medical treatment around the world. Over 28,000 species of plants have been recorded with differenct therapeutic purposes [121]. Therefore, plants constituents have long been regarded as the mainstream materials for drug discovery. In particular, over one third of current anticancer drugs are derived from plant natural products [122]. In this section, the recently isolated plant-derived cyclopeptides and their anticancer properties are discussed. The structures of these compounds are shown in Figure 5 and their activities are listed in Table 2.

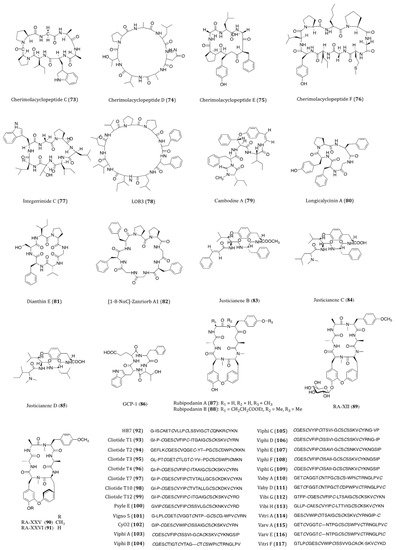

Cherimolacyclopeptides C-F (73–76) were cyclic heptapeptides obtained from the seeds of Annona cherimola in 2004 and 2005. All four compounds exhibited significant in vitro cytotoxicity against KB cells with IC50 values ranging from 0.017 to 0.97 μM [123,124,125]. Although these compounds showed anticancer potential, no further screening on other cancer cell lines or pharmacological investigations of these congeners have been reported thereafter.

Integerrimide C (77), a novel cycloheptapeptide, has been recently isolated from the latex of Jatropha integerrima. The cytotoxicity bioassay indicated its inhibitory effect against KB cells was associated with an IC50 value of 1.7 μM [126]. The discovery of integerrimide C was actually the continuation of studies on the latex of J. integerrima. Previously reported cyclopeptides integerrimides A and B were also the isolates of this particular species and exhibited moderate inhibitory activities against human melanoma (IPC-298) cell proliferation (up to 40% at 50 μM) and human pancreatic carcinoma (Capan II) cell migration (30% and 20% at 50 μM, respectively) [127].

Linoorbitides (LOBs) are a group of cyclopeptides found in flaxseed oil. Actually, flaxseed and its oil have been considered and utilized as anticancer products for many years [128]. In order to investigate whether flaxseed-derived LOBs are cytotoxic to cancer cells, Denis et al. [129]. tested the cytotoxicity of four cyclopeptides derived from flaxseed against A375 (melanoma), SKBR3 and MCF7 cells. Their study showed that LOB3 (78) possessed the highest in vitro potency among the test compounds, yet the minimum concentration of LOBs in serum had to be reached about 400–500 μg/mL for the delivery of its effectiveness. Such concentration is unlikely to be used as a drug through oral administration in humans. Nevertheless, as topical medication, LOB3 could be a potential agent for the treatment of melanoma and other skin cancers. Although flaxseed is well known for its health benefits against cancer, searching for specific compounds derived from flaxseed with high potency is still under way.

Cambodine A (79) was a novel 14-membered ring cyclopeptide extracted from the root barks of Ziziphus cambodiana. The in vitro bioassay showed that it was moderately cytotoxic against the BC-1 (lymphoma) cells with an IC50 value of 11.1 µM, whilst no toxicity was shown against the non-cancerous Vero cells [130].

The species Dianthus superbus is an important anti-inflammatory and diuretic herb in traditional Chinese medicine. Longicalycinin A (80), a cytotoxic cyclopeptide, was first isolated from the extract of D. superbus several years ago. The natural compound showed a growth inhibitory activity against HepG2 cancer cells with an IC50 value of 22.13 µM [131]. This compound had been successfully synthesized by the solid-phase methodology. When acting against in vitro Dalton’s lymphoma ascites (DLA) and Enrlich’s ascites carcinoma (EAC) cells, CTC50 values were determined to be 2.62 and 6.17 µM, respectively [132]. In the study of Tehrani et al., they demonstrated that the synthesized linear and cyclic disulfide heptapeptides of longicalycinin A showed similar inhibitory effect against HepG2 (IC50 = 16.97 and 16.91 µM, respectively) and HT29 (IC50 = 20.38 and 27.68 µM, respectively) cells. However, considering their vulnerability and proapoptotic actions against normal cells (skin fibroblast cells), the linear disulfide heptapeptides were more tempting for promotion as novel anticancer agents [133]. Although longicalycinin A and its analogs can be totally synthesized, the mechanism of actions as well as the in vivo actions of these compounds are yet to be thoroughly studied.

Similar to longicalycinin A, dianthin E (81) is another cyclic peptide isolated from Dianthus superbus. With the IC50 values of >33.3 µM against Hep3B (human hepatic carcinoma), MCF7, A549 and MDA-MB-231 cells, this compound exhibited a selective in vitro cytotoxic activity against HepG2 cells (IC50 = 3.51 µM) [134].

Orbitides are a group of plant cyclic peptides possessing a signature short chain of 5 to 11 residues, they are biosynthesized by ribosomes and characterized by their N-to-C amide bonds, but not disulfide bonds [135]. [1-8-NαC]-Zanriorb A1 (82) was a novel orbitide isolated from the leaves of Zanthoxylum riedelianum with proapoptotic effects. This compound was found to be cytotoxic against Jurkat leukemia T cells with an IC50 value of 218 nM. Regarding its molecular mechanism, it induced remarkable cell death, which would be partially inhibited by the caspase inhibitor Z-VAD-FMK. Moreover, it also induced apoptosis via reducing the levels of mitochondrial membrane potential (Ψmit) and deactivating caspase-3 [136].

Three novel cyclopeptide alkaloids, justicianenes B-D (83–85) were isolated from the Justicia procumbens L. These three compounds were evaluated their cytotoxicity against human breast cancer MCF-7, cervix carcinoma HeLa, and lung cancer A549 and H460. However, only justicianene D displayed weak cyctotoxicity against MCF-7 cells with IC50 of 90 μM [137].

Seven novel ginseng cyclopeptides (GCPs) were isolated and showed anti-proliferative activities in gastric cancer SGC-7901 cells, in which GCP-1 (86) showed the most potency with IC50 value of 37.8 μM. Regarding its molecular mechanism, it induces apoptosis by activating the caspases and regulating thioredoxin (Trx)-dependent pathways, including signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs)-p38 and JNK pathways [138].

Cyclotides are the macrocyclic cysteine-rich peptides derived from plants, and featured with three disulfide bonds, 28 to 37 amino acids and a head-to-tail cyclized backbone in a knotted arrangement [139]. The typical structure of cyclotides makes them broadly bioactive and remarkably stable against enzymatic and thermal degradation [140].

In traditional Chinese medicine, the roots and rhizomes of Rubia plants have been used for thousands of years to treat menoxenia, contusion, rheumatism and tuberculosis [141]. Rubiaceae-type cyclopeptides (RAs) are referred to as natural cyclopeptides derived from Rubia. Up to now, 56 RAs have been isolated from Rubia plants. Due to their characteristic bicyclic structures and significant anticancer activities, RAs have gained much attention in recent years [142]. Rubipodanin A (87), a novel cyclic hexapeptide obtained from the roots and rhizomes of R. podantha, is the first naturally identified N-desmonomethyl RA. This compound was tested to be cytotoxic against three cancer cell lines including HeLa, A549 and SGC-7901 (human gastric cancer cell), with IC50 values ranging from 3.80 to 7.22 μM. However, when compared to the previously known cyclopeptide RA-V, in which two N-methyl groups are present in its backbone skeleton, the cytotoxicity of rubipodanin A was considered much weaker. In regards to its mechanisms, rubipodanin A exhibited a down-regulating effect on the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway, which largely contributed to its anticancer activity [143]. Derived from the same plant species, another new RA with potent cytotoxicity was designated rubipodanin B (88). This compound showed IC50 values of 1.47 μM, 0.69 μM and 3.37 μM in MDA-MB-231, SW620 (human colorectal adenocarcinoma) and HepG2 cells respectively. Nevertheless, the anticancer activity of rubipodanin B was not associated with any down-regulation of the NF-κB signaling pathway [144]. Another cyclopeptide compound from RA family is RA-XII (89), which derived from R. yunnanensis, showed inhibitory effects on tumor growth and metastasis IC50 value of 606 nM and 96 nM on human breast cancer 4T1 cells for 24 and 48 h, respectively [145,146,147]. RA-XII also exerts antitumor activity by supressing autophagy via activating Akt-mTOR and NF-κB pathways in colocrectal cancer SW620 and HT29 cells [148]. RA-XXV (90) and RA-XXVI (91) are two new bicyclic hexapeptides, which isolated from the roots of R. cordifolia L. RA-XXV showed cytotoxic activity against human promyelocytic leukemia HL-60 and human colorectal carcinoma HCT 116 cells with IC50 of 62 nM and 28 nM, respectively. RA-XXVI showed cytotoxic activity agains HL-60 and HCT 116 cells with with IC50 of 66 nM and 51 nM, respectively [149]. To further determine RA compounds underlying mechanism, a wide screening of its molecular targets is desperately needed.

The intensive studies of famous traditional Chinese herb Hedyotis biflora had led to the isolation of HB7 (92), which is considered a potential anticancer cyclotide. By means of MTT assay, HB7 showed in vitro cytotoxicity against four pancreatic cancer cell lines BxPC3, Capan2, MOH-1 and PANC1 with IC50 values of 0.68, 0.45, 0.33 and 0.36 µM, respectively. At a non-toxic concentration of 0.05 µM, HB7 even inhibited cellular migration and invasion of Capan2 cells. When extrapolated to the in vivo xenograft mouse models, this cyclotide was observed to significantly suppress tumor growth without exhibiting any obvious organ injury or toxicity. Based on the results above, the cytotoxicity of HB7 was plausibly related to the different net charges of the cyclotide [150]. Because of its decent anticancer potential, the specific underlying mechanism of action of HB7 deserves further investigation.

Cliotides T1-T4 (93–96) were four novel cyclotides isolated from the tropical plant Clitoria ternatea, belonging to the Fabaceae family. With the prevalent distribution in almost every tissue of C. ternate, the extraction of these four cyclotides is rather efficient. These cyclotides have been confirmed to be heat-stable cysteine-rich peptides. When incubated with HeLa cells, all these four compounds yielded significant cytotoxicity with IC50 values ranging from 0.6 to 8.0 µM. Among the four, T1 and T4 were the most potent ones (IC50 = 0.6 µM) [151]. Cliotides T2 (94), T4 (96), T7 (97), T10 (98) and T12 (99) also exhibited significant cytotoxicity towards A549 cells (IC50 values ranging from 0.21 to 7.59 µM) as well as paclitaxel-resistant A549 cells (IC50 values ranging from 0.45 to 7.92 µM). Intriguingly, the IC50 values of these five test compounds were decreased by two to four folds when incubated with paclitaxel [152]. Nevertheless, the chemosensitizing ability of the cliotides became evidenced in drug-resistant cell lines, which deserves further studies on the aspects of compound charge status and in vivo efficacy. Apart from anticancer potential, cliotides, T1 to T4 in particular, also exhibited notable antimicrobial properties, particularly E. coli [152].

Among the cyclotides isolated from Psychotria leptothyrsa var. longicarpa, psyle E (100) was the most cytotoxic one. The IC50 value of psyle E against human lymphoma cell line U937-GTB was determined to be 0.76 µM. According to the reported SAR assessment, the linear structure of psyle E was required to maintain its potent cytotoxicity [153].

Vigno 5 (101) was a cyclotide discovered in Viola ignobilis [154]. This compound showed its in vitro cytotoxicity against HeLa cells with an IC50 value around 2.5 µM. Due to the complexity of its chemical structure and technical limitation, only the primary structure of vigno 5 had been elucidated so far. In the study of Esmaeili el al., vigno 5 induced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner accompanied by nuclear shrinkage, DNA fragmentation, caspase activation and the cleavage of PARP. The vigno 5 induced-apoptosis was found to be caspase-dependent, explicitly caspase-3. To the induction of apoptotic events and mitochondrial dysfunction, a decreased level of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and an increased level of pro-apoptotic Bax were observed in the vigno 5-treated HeLa cells [155].

Cycloviolacin O2 (CyO2, 102), a potent cytotoxic cyclotide, was first isolated from the plant Viola odorata L. (Violaceae). The presence of glutamic acid in cycloviolacin O2 contributed much to its cytotoxic activity against U937 GTB (human lymphoma) cells with an IC50 value of 0.75 μM [156]. Besides, CyO2 also exhibited concentration-dependent cytotoxicities towards CCRF-CEM (leukemia cell line), NCI-H69 (small cell lung cancer) and HT29 cells with IC50 values of 0.3, 1.2 and 5.3 μM, respectively [157]. Disruption of the U937 cell membranes by CyO2 further indicated its membrane-disrupting activity while exerting cytotoxicity [158]. Gerlach et al. even demonstrated that CyO2 induced pore formation specifically in highly proliferating tumor cells [159]. In addition, CyO2 was also reported to exhibit bioactivities against gram-negative bacteria and HIV-1 virus via multipleregulatory mechanisms [153,160]. However, another study on the evaluation of toxicity and antitumor activity of CyO2 in mice showed that its antitumor effects were little or even absent at sublethal doses. It is worth noting that quick lethality of CyO2 was observed at 2 mg/kg whilst no abnormal signs were seen at the dose of 1.5 mg/kg in the experimental mice [157]. Thus, there is a great disparity between the results of the in vitro and in vivo experiments. For further investigation of this cyclotide, problems such as low in vivo efficacy need to be addressed.

Characterized by the macrocyclic backbones, cyclotides viphis A-G (103–109) were isolated from Viola philippica. These eight compounds were cytotoxic to human melanoma (MM96L), HeLa and human gastric adenocarcinoma (BGC-823) cells and human normal fibroblast cells (HFF-1). When applied at 3.24 and 3.17 µM, viphis D-E showed no activity against BGC-823 cell; however all these eight cyclotides displayed cytotoxicities against many cancer cell lines with IC50 values ranging from 1.03 to 15.5 µM. From the results of SAR assessments, hydrophobicity and glutamic acid residue of loop 1 are suggested of great importance for their cytotoxic activities. Further biochemical assays revealed that these viphis could be influenced by minimal sequential changes for alterations of their bioactivities [161].

Vabys A (110) and D (111) were two cyclotides derived from Viola abyssinica, a plant growing at an altitude over 3400 m. Both compounds contain charged residues; however different net charges lead to different bioactivities. Vabys A and D exhibited cytotoxicities against U-937 lymphoma cells in a dose-dependent manner, with IC50 values of 2.6 and 7.6 µM, respectively [162].

Isolated from the alpine violet Viola biflora, vibis G (112) and H (113) were two bracelet cyclotides. These two compounds showed similar cytotoxic potency (IC50 = 0.96 and 1.6 µM, respectively) against lymphoma U-937 GTB cells [163].

A bioactivity-guided fractionation of Viola tricolor led to the isolation of a cluster of highly similar cyclotides, among which vitri A (114), varv A (115) and varv E (116) were found to be cytotoxic agents. Two human cancer cell lines, U-937 GTB (IC50 = 0.6, 6 and 4 µM, respectively) and myeloma RPMI-8226/s (IC50 = 1, 3 and 4 µM, respectively) were used in the cytotoxicity assays. Sequence determination and SAR analysis demonstrated that differences in the net charges and cationic amino acid residues in these cyclotides are extremely crucial for their cytotoxicities [164]. Assessment of the cytotoxic activities against human malignant glioblastoma (U251), MDA-MB-231, A549, DU145 and human hepatoma (BEL7402) cell lines showed the inhibitory activities of vitri A (114) with IC50 values ranging from 0.97 to 1.91 µM and vitri F (117) with IC50 values ranging from 0.85 to 1.97 µM. Importantly, the distribution of highly hydrophobic residues on the surface was highlighted for the cytotoxic activities of these cyclotides [165]. Undeniably, plant-derived cyclotides are the intriguing candidates for drug development as anticancer therapeutics. Owing to the abundant source of cyclotides, V. tricolor warrants further studies for the identification of new bioactive compounds and their anticancer mechanism of actions.

Table 2. Terrestrial plant-derived anticancer cyclopeptides.

|

Name |

Biological Source |

Anticancer Activity |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Cherimolacyclopeptides C-F (73–76) |

Seeds of Annona cherimola |

Cytotoxicity against KB cell. (IC50 = 0.017 to 0.97 µM) |

|

|

Integerrimide C (77) |

Latex of Jatropha integerrima |

Cytotoxicity against KB (IC50 = 1.7 µM) cell. |

[126] |

|

LOB3 (78) |

Flaxseed oil |

Cytotoxicty against A375, SKBR3 and MCF7 cells. |

|

|

Cambodine A (79) |

Root bark of Ziziphus cambodiana |

Cytotoxicity against BC-1 (IC50 = 11.1 µM) cell. |

[130] |

|

Longicalycinin A (80) |

Dianthus superbus |

Growth inhibitory activity against HepG2 (IC50 = 22.13 μM) cell. |

|

|

Dianthin E (81) |

Dianthus superbus |

Cytotoxicity against HepG2 (IC50 = 3.51 μM) cell. |

[134] |

|

[1-8-NαC]-Zanriorb A1 (82) |

Leaves of Zanthoxylum riedelianum |

Cytotoxicity against Jurkat leukemia T cell (IC50 = 218 nM). |

[136] |

|

Justicianenes B-D (83–85) |

Justicia procumbens L. |

Justicianene D displayed cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells (IC50 = 90 μM). |

[137] |

|

GCP-1 (86) |

Ginseng |

Cytotoxicity against SGC-7901 cells (IC50 = 37.8 μM). |

[138] |

|

Rubipodanin A (87) |

Roots and rhizomes of Rubia podantha |

Cytotoxicity against HeLa, A549 and SGC-7901 cells. (IC50 = 3.80 to 7.22 μM) |

[143] |

|

Rubipodanin B (88) |

Rubia podantha |

Cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 (IC50 = 1.47 μM), SW620 (IC50 = 0.69 μM) and HepG2 (IC50 = 3.37 μM) cells. |

[144] |

|

RA-XII (89) |

Rubia yunnanensis |

Inhibitory effects on 4T1 ((IC50 = 606 nM and 96 nM for 24 and 48 h, respectively), SW260 and HT29 cells. |

|

|

RA-XXV (90) |

Roots of Rubia cordifolia L. |

Cytotoxicity against HL-60 ((IC50 = 62 nM) and HCT116 cells ((IC50 = 28 nM). |

[149] |

|

RA-XXVI (91) |

Roots of Rubia cordifolia L. |

Cytotoxicity against HL-60 ((IC50 = 66 nM) and HCT116 cells ((IC50 = 51 nM). |

[149] |

|

HB7 (92) |

Hedyotis biflora |

Cytotoxicity against BxPC3 (IC50 = 0.68 μM), Capan2 (IC50 = 0.45 μM), MOH-1 (IC50 = 0.33 μM) and PANC1 (IC50 = 0.36 μM) cells. |

[150] |

|

Cliotides T1-T4 (93–96), cliotide T7 (97), cliotide T10 (98), cliotide T12 (99) |

Clitoria ternatea |

Cliotides T1-T4: cytotoxicity against HeLa (IC50 = 0.6 to 8.0 μM) cell. Cliotides T2, T4, T7, T10 and T12: cytotoxicity against A549 (IC50 = 0.21 to 7.59 μM) and A549/paclitaxel (IC50 = 0.45 to 7.92 μM) cells. |

|

|

psyle E (100) |

Psychotria leptothyrsa var. longicarpa |

Cytotoxicity against U937-GTB IC50 = 0.76 μM) cell. |

[153] |

|

Vigno 5 (101) |

Viola ignobilis |

Pro-apoptotic activity on HeLa cell. |

|

|

Cycloviolacin O2 (CyO2) (102) |

Viola odorata L. |

Cytotoxicity against U937 GTB (IC50 = 0.75 μM), CCRF-CEM, NCI-H69 and HT29 cells. |

|

|

Viphi A-G (103–109) |

Viola philippica |

Cytotoxicity against MM96L, HeLa, BGC-823, HFF-1 cells, but viphi D and E showed no activity against BGC-823 cell. (IC50 = 1.03 to 7.92 μM) |

[161] |

|

Vaby A (110) and D (111) |

Viola abyssinica |

Cytotoxicity against U-937 (IC50 = 2.6 and 7.6 μM, respectively) cell. |

[162] |

|

Vibi G (112) and H (113) |

Viola biflora |

Cytotoxicity against U-937 GTB (IC50 = 0.96 and 1.6 μM, respectively) cell. |

[163] |

|

Vitri A (114) |

Viola tricolor |

Cytotoxicity against U-937 GTB (IC50 = 0.6 µM) and RPMI-8226/s (IC50 = 1 µM) cells. Cytotoxicity against U251, MDA-MB-231, A549, DU145 and BEL7402 cells (IC50 = 3.07 to 6.03 μM). |

|

|

Varv A (115) and E (116) |

Viola tricolor |

Cytotoxicity against U-937 GTB (IC50 = 6 and 4 µM, respectively) and RPMI-8226/s (IC50 = 3 and 4 µM, respectively) cells. |

[164] |

|

Vitri F (117) |

Viola tricolor |

Cytotoxicity against U251, MDA-MB-231, A549, DU145 and BEL7402 cel ls (IC50 = 2.74 to 6.31 μM) |

[165] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22083973