Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are emerging crystalline polymeric materials with highly ordered intrinsic and uniform pores.

- covalent organic frameworks

- synthesis

- functionalities

1. Introduction

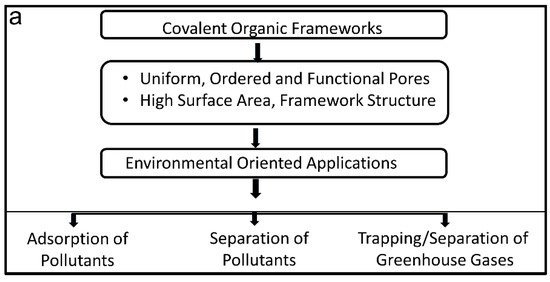

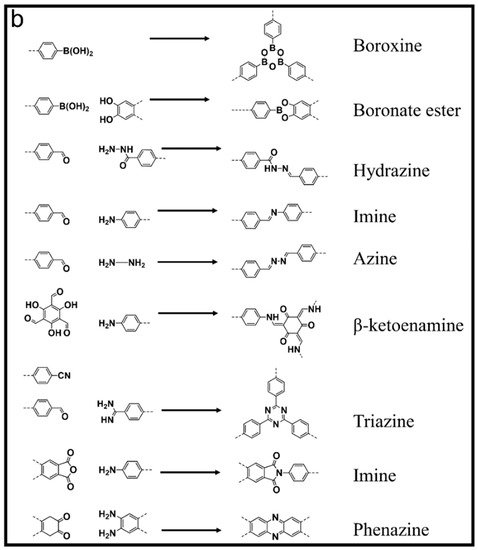

Purification processes such as distillation, evaporation, concentration, and crystallization are important in basic research as well as playing an important role in industries. These processes, however, operate at the expense of environmental deterioration by consuming an enormous amount of energy, further promoting global warming. Industrial effluents also contain a large amount of chemical and bio-chemical hazardous ingredients polluting the already scarce freshwater resources. Moreover, many industries waste a large amount of precious chemical compounds and organic solvents due to the lack of economical separation/purification materials. Therefore, purification processes with low energy requirements may benefit the environment by saving energy on one hand and saving important capital costs on the other. In recent years, adsorption- (entrapment) and membrane (size exclusion)-based purification have attracted immense research and industrial interest due to their low energy consumption as well as simple and environmentally friendly operation. Various amorphous materials such as hyper-cross-linked polymers (HCPs) [1,2], porous organic polymers (POPs) [3,4], conjugated microporous polymers (CMPs) [5,6,7], and activated carbon [8,9,10]; and crystalline materials such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [11,12,13,14] and zeolites [15,16,17,18,19], have shown excellent preliminary separation performance. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are a class of crystalline framework material synthesized from purely organic building blocks. Their synthesis involves reticular chemistry, which gives immense freedom of pre-design. Their pore geometry, size, and functionalities can be pre-determined by choosing building units from a large bank. Yaghi and co-workers first reported COFs based on boroxine and boronate ester rings [20]. These COFs, however, are prone to deformation in the presence of even trace amounts of humidity rendering them unsuitable in aqueous conditions. Later, imine-based COFs were reported to have superior chemical and solvent stability. Banerjee and co-workers prepared β-ketoenamine COFs with exceptional stability at high temperatures and in extreme acidic and basic conditions [21]. Similarly, Thomas and co-workers reported triazine-based COFs prepared at 400 °C, exhibiting excellent thermo-chemical stabilities [22]. Some of the important applications and various types of COFs are shown in Scheme 1 and Figure 1, respectively. Among many important aspects, COFs offer pore post-functionalization due to their organic nature, for specific desirable applications such as gas storage [23,24,25], catalysis [26,27], electronic devices [11,28], electrode material for batteries [29,30,31,32], etc.

The most attractive feature of COFs is their framework structure with uniform and extended porous channels, attracting the interest of scientists in the purification/separation field. Earth’s environment is under threat from the increasing disposal of hazardous ingredients such as heavy metals and poisonous organic and bio-organic chemicals [33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Due to their distinct features, COFs represent themselves as viable alternative materials to address these issues [40,41]. Suitable pore designs and functionalities can render COFs as adsorbents for trapping hazardous metals, organic and bio-pollutants, and greenhouse gases [39,42,43,44,45,46,47]. As adsorbents, COF pores attract and trap pollutants based on their affinity towards functional COFs. COFs are also touted as excellent robust materials to fabricate separation membranes [48,49]. In the membrane form, pollutants are separated based on diffusion rates relying on the size, geometry, or charge of permeate and retentate. COFs have been reported to remove toxic components from both gases and liquids. Moreover, functionally decorated COFs can facilitate catalytic degradation of pollutants and convert them to clean energy. Our group has extensively worked on metal oxides and their composites for the application of photo- and electro-catalytic process [50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], but recently we have shifted our focus towards COFs due to their excellent characteristic properties. Although COFs were first reported in 2005, their environmental applications have only attracted interest very recently [68]. Since then, COFs have been extensively explored for various environmentally related applications. We believe that an up-to-date account is urgently required for scientists in this field.

2. Evolution of COF Synthesis through Time

3. Important Aspects of COF Materials towards Cleaner Environment

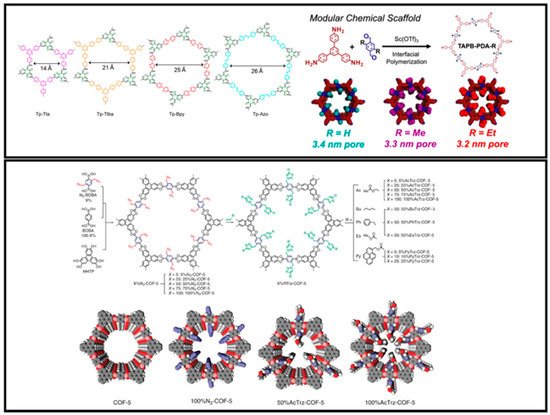

Industries are polluting our environment in two ways: (i) disposal of hazardous chemicals in water reservoirs; (ii) and greenhouse gases into the air. Materials with advanced functionalities to trap these hazardous chemicals and gases are urgently required to address these issues [91]. COFs are materials that have intrinsic, uniform, ordered and tailorable pores along with high surface area, making them very attractive for trapping and separating these hazardous molecules. COFs with multi-functional pores have extended their applicability in environmental cleansing. Due to their high surface area and ordered porous channels, they can not only be used to trap/store gas molecules but can also function as separating media to remove unwanted chemicals from the waste solution. This application can reduce environmental pollution as well as help in the recovery of precious solvents to be re-used in industries, rendering the whole operation environmentally and economically friendly. Recent development has yielded COFs with extraordinary stability in harsh acidic and basic conditions, rendering them highly desirable in industrial purification and trapping applications [21,92]. The rational design of COFs needs careful consideration of many aspects for intended purification applications. In this section, we will discuss some important aspects of COFs such as structure, morphology, and charge of their pores, as well as their stability, which makes them ideal alternative materials for environmental applications.

3.1. Pore Structure

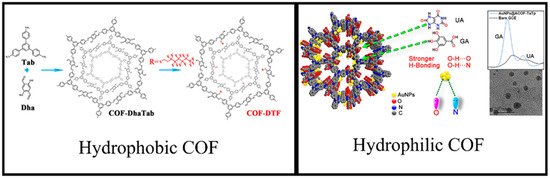

3.2. Hydrophobicity/Hydrophilicity of COFs

3.3. Structural Stability

3.4. Pore Charge

Pore charge is a crucial factor in the separation or trapping of hazardous chemicals through electrostatic interactions. According to Donnan’s theory, a negative charge-separating barrier will repulse divalent anions whereas divalent cations will be attracted. Therefore, if the negatively charged separating barrier is an adsorption agent then the cations will be trapped inside the matrix, but if the barrier is a membrane then the positively charged ions will transport more efficiently leaving anions in the feed. The same phenomenon is applied to the oppositely charged separating barrier. So far, very little attention has been given to design-charged COFs. Ma and co-workers introduced cationic sites in the COF (EB-COF:Br) by reacting 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucnol and ethidium bromide (EB) (3,8-diamino-5-ethyl-6-phenylphenanthridinium bromide) [106]. Similarly, Oakey et al. prepared a negatively charged COF by introducing carboxyl functional groups in the COF’s backbone and introduced them as fillers in the preparation of mixed matrix membranes [107]. In addition to the narrow size distribution of COF pores, the deprotonated -COOH− enhanced the rejection of bovine serum albumin (negatively charged protein) to as high as 81% at a COF loading of 0.8%. A similar approach was adopted to prepare a COF with modifiable carboxyl functional groups to prepare 12 COFs with variable aperture size and was self-assembled as continuous membranes [108]. It is expected that the synthesis of COFs based on charged pores for environmental application will attract more attention in coming years by incorporating functional groups such as hydroxyl, sulfonic acid, amine, etc.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en14082267