Early follicles' development, especially the activation of primordial follicles, is strictly modulated by a network of signaling pathways. Recent advance in ovarian physiology has been allowed the development of several therapies to improve reproductive outcomes by manipulating early folliculogenesis. Among these, in vitro activation (IVA) has been recently developed to extend the possibility of achieving genetically related offspring for patients with premature ovarian insufficiency and ovarian dysfunction. This method was established based on basic science studies of the intraovarian signaling pathways: the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt and the Hippo signaling pathways. These two pathways were found to play crucial roles in folliculogenesis from the primordial follicle to the early antral follicle. Following the results of rodent experiments, IVA was implemented in clinical practice. There have been multiple recorded live births and ongoing pregnancies. Further investigations are essential to confirm the efficacy and safety of IVA before used widely in clinics.

- in vitro activation

- hippo signaling pathway

- PI3K/Akt/FOXO3 pathway

1. Introduction

The majority of achievements in medical science practice are based on basic scientific research. Improved understanding of reproductive physiology has also allowed remarkable advances in artificial reproductive technologies, giving a higher chance to achieve parenthood for millions of infertile couples [1].

As a consequence of global modernization, a higher number of advanced aged infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) have been diagnosed in the last decades [2][3]. Due to innovations in oncological treatment, the number of cancer survivors at the reproductive age has been increasing, leading to a higher prevalence of premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) [4]. In addition, there is an increasing necessity for fertility preservation (FP).

During last decades, oocyte donation which cannot fulfill wishes of patients to give birth to genetically related offspring is often the option for patients with DOR and POI. To expand reproductive possibilities to DOR and POI patients, considerable efforts to investigate molecular mechanisms underlying folliculogenesis, leading to a variety of new approaches including follicle regeneration, rejuvenation, and activation [5].

Among these, the activation of early follicles (EFs) including primordial, primary, secondary, and early antral follicles has been recently achieved. For developing the efficient activation system, many basic studies using the animal-model were conducted to identify the signaling pathways governing the activation of early follicles.

IVA has been recently introduced and gradually implemented in clinical practice. This innovation was established from numerous animal experiments, including genetic manipulation studies illustrating the molecular mechanism of two involving signaling pathways in folliculogenesis. The first one is the PI3K/Akt/forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) pathway, which has a crucial role in the activation of primordial follicles (PFs) [6][7][8][9]. The other one is the Hippo signaling pathway which has been recently illustrated to modulate the progress of follicles from secondary to antral stage [10][11]. Based on results obtained from animal-model and in vitro experiments, IVA was implemented to treat POI and DOR women. Healthy babies and other encouraging outcomes have been reported from different groups [11][12][13][14][15][16][17]. Furthermore, several studies suggested the correlation between Hippo pathway’s genes abnormality and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) [18][19][20], leading to a possibility to ameliorate reproductive outcomes of PCOS patients by manipulating the Hippo signaling pathway [21].

2. The Activation of the EFs In Vitro

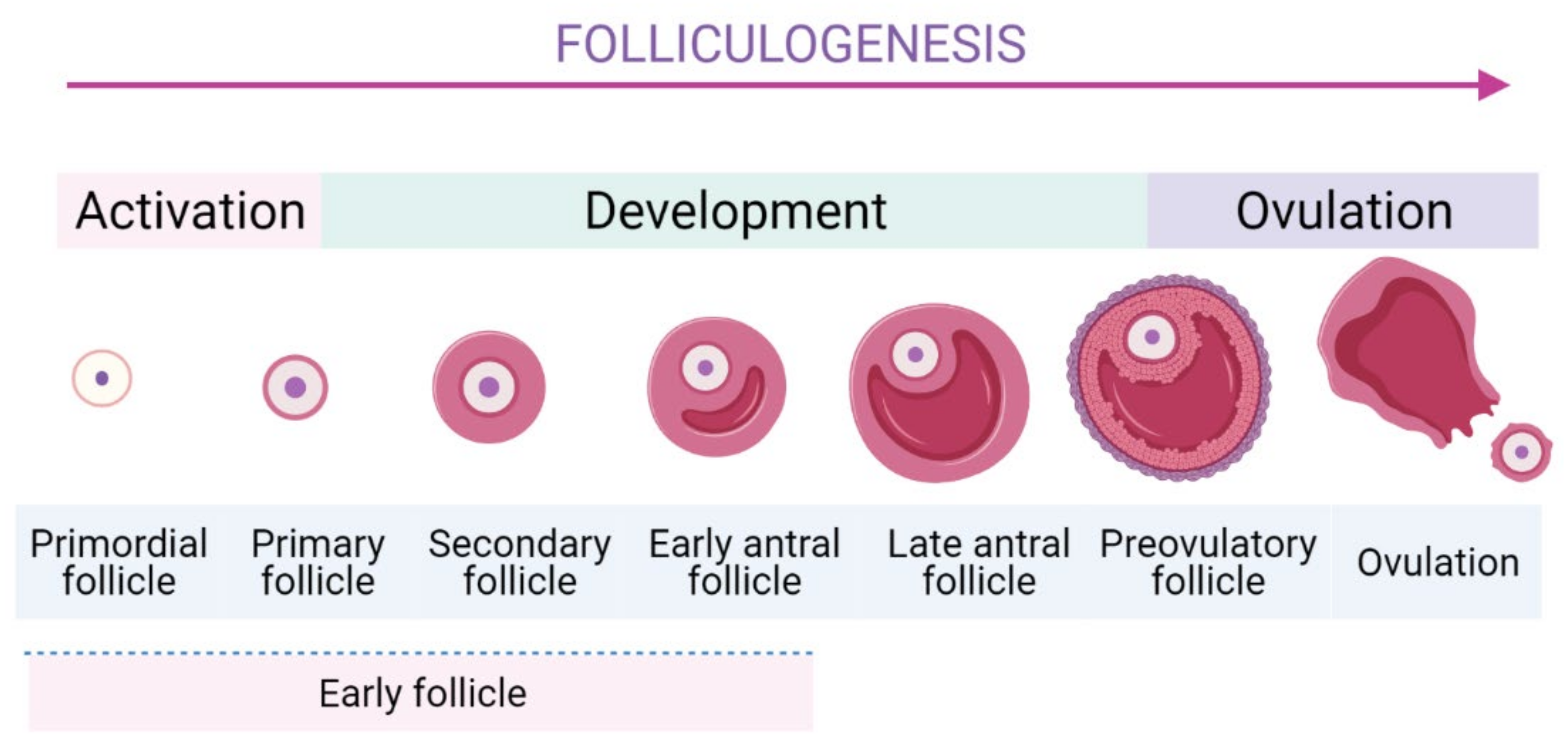

Folliculogenesis is a complicated process which is generally divided into two stages: the first one is early stage from the PFs to the early antral follicles stage, and the latter one is the early antral follicles to ovulatory stage (Figure 1) [22]. In mammalian ovaries, EFs are the largest population comprising of the PFs, primary follicles, secondary ones, and early antral follicles.

To form the growing follicles, a small number of PFs are cyclically and periodically recruited in the growing pool. The most specific feature of PFs is their long-term dormancy and survival for several decades, ensuring the longevity for female reproductive possibility. Thus, they represent a finite source of ovarian follicles and their recruitment is an indispensable step as it determines reproductive lifespan [23][24]. The activation of EFs is modulated strictly to ensure only a small number of PFs can be activated [10][25]. Subsequently, they undergo continuous folliculogenesis to develop to later stages of development until the ovulation occurs. In PF, a dormant oocyte is enveloped by a single layer of flattened granulosa cells (GCs). In response to stimulators of PI3K/Akt pathway, mTORC1 in GCs is activated [26] and then GCs start to proliferate, cuboidalize, and exclude SMADs proteins [26][27]. These dynamic changes are important signals to initiate the activation of PFs [27]. Moreover, several genes expressed in the GCs were identified to promote the PFs’ activation [26][28]. The internal communication between oocyte and GCs is crucial during follicle development [26].

Although the number of PFs decreases gradually through apoptosis and recruitment, the pool of PFs is not completely exhausted even at the age of menopause [24]. Additionally, it is reported that three out of four POI patients have residual dormant PFs remaining in their ovaries [29]. PFs are the ideal population for PF as they could resist chemotherapies and are well-preserved during cryopreservation [30]. Therefore, consideration to develop an in vitro approach to control the activation of PFs has attracted extensive interest in the past decades [24]. Recently, a number of innovative approaches have been suggested to promote the EFs’ development by using key agents to imitate the physiology ovarian environment.

The first in vitro experiment of PFs was conducted on mice by culturing the whole intact ovaries in serum-containing medium. The spontaneous activation of a small number of PFs in the medulla region, which is similar to the first wave of physiologic PFs activation, was noted. Additionally, the addition of epidermal growth factor (EGF) could enhance the follicle recovery [31]. In bovine and ovine species, culturing ovarian cortex with serum-free medium was also found to activate the PFs [32][33][34]. In human ovary, PFs activated spontaneously in the cultured ovarian cortex regardless of the presence of serum [35][36][37]. The two-step culture procedure using activin comprised of ovarian cortical strips culture in human followed by isolation and culture of the acquired secondary follicles was reported to yield antral stage follicles from the PFs. However, as the timing of follicle growth in this system is highly irregular, the finding has yet to be repeated [37].

These findings suggested that the PFs could be suppressed under the physiological environment, or there are in vitro factors stimulating the PF activation [9]. Although the number of activated PFs was limited in these studies, these encouraging findings placed the important foundation for the development of the activation of EFs in vitro controlled environment. Subsequently, accumulated understanding in mechanisms modulating the activation of EFs has been achieved, leading to a step closer to its potential clinical applicability. The activation of EFs is strictly governed by a number of signaling pathways and components as discussed in the following sections.

3. Summary

Numerous researches provided scientific evidence for pathways underlying the IVA approach. IVA offered encouraging outcomes to the poor prognostic infertile women in the clinic. Individualization in treatment is a crucial aspect of clinical practice. In patients with DOR or early stage of POI, drug-free IVA is more beneficial compared to conventional IVA as it decreases the invasiveness of surgical approach and avoids the unfavorable effects of tissue culture on follicles. In terms of FP, IVA should be applied to only patients with low ovarian reserve and the requirement for motherhood achievement is urgent.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22073785

References

- Niederberger, C.; Pellicer, A.; Cohen, J.; Gardner, D.K.; Palermo, G.D.; O’Neill, C.L.; Chow, S.; Rosenwaks, Z.; Cobo, A.; Swain, J.E.; et al. Forty years of IVF. Fertil. Steril. 2018, 110, 185–324.e5.

- Martin, J.A.; Hamilton, B.E.; Osterman, M.J.K.; Driscoll, A.K. Births: Final Data for 2018. Natl. Vital. Stat. Rep. 2019, 68, 1–47.

- Mathews, T.J.; Hamilton, B.E. Mean Age of Mothers is on the Rise: United States, 2000–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2016, 232, 1–8.

- Suhag, V.; Sunita, B.S.; Sarin, A.; Singh, A.K.; Dashottar, S. Fertility preservation in young patients with cancer. South Asian J. Cancer 2015, 4, 134–139.

- Griesinger, G.; Fauser, B. Drug-free in-vitro activation of ovarian cortex; Can it really activate the ‘ovarian gold reserve’? Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 187–189.

- Liu, K.; Rajareddy, S.; Liu, L.; Jagarlamudi, K.; Boman, K.; Selstam, G.; Reddy, P. Control of mammalian oocyte growth and early follicular development by the oocyte PI3 kinase pathway: New roles for an old timer. Dev. Biol. 2006, 299, 1–11.

- Adhikari, D.; Liu, K. Molecular mechanisms underlying the activation of mammalian primordial follicles. Endocr. Rev. 2009, 30, 438–464.

- Kawamura, K.; Kawamura, N.; Hsueh, A.J. Activation of dormant follicles: A new treatment for premature ovarian failure? Curr. Opin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 28, 217–222.

- Reddy, P.; Zheng, W.; Liu, K. Mechanisms maintaining the dormancy and survival of mammalian primordial follicles. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010, 21, 96–103.

- Hsueh, A.J.; Kawamura, K.; Cheng, Y.; Fauser, B.C. Intraovarian control of early folliculogenesis. Endocr. Rev. 2015, 36, 1–24.

- Kawamura, K.; Cheng, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Deguchi, M.; Sato, Y.; Takae, S.; Ho, C.H.; Kawamura, N.; Tamura, M.; Hashimoto, S.; et al. Hippo signaling disruption and Akt stimulation of ovarian follicles for infertility treatment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 17474–17479.

- Suzuki, N.; Yoshioka, N.; Takae, S.; Sugishita, Y.; Tamura, M.; Hashimoto, S.; Morimoto, Y.; Kawamura, K. Successful fertility preservation following ovarian tissue vitrification in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod. 2015, 30, 608–615.

- Zhai, J.; Yao, G.; Dong, F.; Bu, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Sato, Y.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Dai, S.; et al. In Vitro Activation of Follicles and Fresh Tissue Auto-transplantation in Primary Ovarian Insufficiency Patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016, 101, 4405–4412.

- Fabregues, F.; Ferreri, J.; Calafell, J.M.; Moreno, V.; Borrás, A.; Manau, D.; Carmona, F. Pregnancy after drug-free in vitro activation of follicles and fresh tissue autotransplantation in primary ovarian insufficiency patient: A case report and literature review. J. Ovarian Res. 2018, 11, 76.

- Lunding, S.A.; Pors, S.E.; Kristensen, S.G.; Landersoe, S.K.; Jeppesen, J.V.; Flachs, E.M.; Pinborg, A.; Macklon, K.T.; Pedersen, A.T.; Andersen, C.Y.; et al. Biopsying, fragmentation and autotransplantation of fresh ovarian cortical tissue in infertile women with diminished ovarian reserve. Hum. Reprod. 2019, 34, 1924–1936.

- Kawamura, K.; Ishizuka, B.; Hsueh, A.J.W. Drug-free in-vitro activation of follicles for infertility treatment in poor ovarian response patients with decreased ovarian reserve. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 245–253.

- Ferreri, J.; Fàbregues, F.; Calafell, J.M.; Solernou, R.; Borrás, A.; Saco, A.; Manau, D.; Carmona, F. Drug-free in-vitro activation of follicles and fresh tissue autotransplantation as a therapeutic option in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency. Reprod. Biomed. Online 2020, 40, 254–260.

- Maas, K.; Mirabal, S.; Penzias, A.; Sweetnam, P.M.; Eggan, K.C.; Sakkas, D. Hippo signaling in the ovary and polycystic ovarian syndrome. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2018, 35, 1763–1771.

- Chen, Z.J.; Zhao, H.; He, L.; Shi, Y.; Qin, Y.; Li, Z.; You, L.; Zhao, J.; Liu, J.; Liang, X.; et al. Genome-wide association study identifies susceptibility loci for polycystic ovary syndrome on chromosome 2p16.3, 2p21 and 9q33.3. Nat. Genet. 2011, 43, 55–59.

- Louwers, Y.V.; Stolk, L.; Uitterlinden, A.G.; Laven, J.S. Cross-ethnic meta-analysis of genetic variants for polycystic ovary syndrome. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, E2006–E2012.

- Hsueh, A.J.W.; Kawamura, K. Hippo signaling disruption and ovarian follicle activation in infertile patients. Fertil. Steril. 2020, 114, 458–464.

- Telfer, E.E.; Zelinski, M.B. Ovarian follicle culture: Advances and challenges for human and nonhuman primates. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 1523–1533.

- Nagamatsu, G.; Shimamoto, S.; Hamazaki, N.; Nishimura, Y.; Hayashi, K. Mechanical stress accompanied with nuclear rotation is involved in the dormant state of mouse oocytes. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaav9960.

- Fabbri, R.; Zamboni, C.; Vicenti, R.; Macciocca, M.; Paradisi, R.; Seracchioli, R. Update on oogenesis in vitro. Minerva Ginecol. 2018, 70, 588–608.

- Devenutto, L.; Quintana, R.; Quintana, T. In vitro activation of ovarian cortex and autologous transplantation: A novel approach to primary ovarian insufficiency and diminished ovarian reserve. Hum. Reprod. Open 2020, 2020, hoaa046.

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, H.; Xu, J.; Su, Y. Current mechanisms of primordial follicle activation and new strategies for fertility preservation. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 27, gaab005.

- Hardy, K.; Mora, J.M.; Dunlop, C.; Carzaniga, R.; Franks, S.; Fenwick, M.A. Nuclear exclusion of SMAD2/3 in granulosa cells is associated with primordial follicle activation in the mouse ovary. J. Cell Sci. 2018, 131, jcs218123.

- Meinsohn, M.C.; Hughes, C.H.K.; Estienne, A.; Saatcioglu, H.D.; Pépin, D.; Duggavathi, R.; Murphy, B.D. A role for orphan nuclear receptor liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1, NR5A2) in primordial follicle activation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1079.

- De Vos, M.; Devroey, P.; Fauser, B.C. Primary ovarian insufficiency. Lancet 2010, 376, 911–921.

- Devos, M.; Grosbois, J.; Demeestere, I. Interaction between PI3K/AKT and Hippo pathways during in vitro follicular activation and response to fragmentation and chemotherapy exposure using a mouse immature ovary model. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 102, 717–729.

- Eppig, J.J.; O’Brien, M.J. Development in vitro of mouse oocytes from primordial follicles. Biol. Reprod. 1996, 54, 197–207.

- Wandji, S.A.; Srsen, V.; Voss, A.K.; Eppig, J.J.; Fortune, J.E. Initiation in vitro of growth of bovine primordial follicles. Biol. Reprod. 1996, 55, 942–948.

- Fortune, J.E.; Kito, S.; Wandji, S.A.; Srsen, V. Activation of bovine and baboon primordial follicles in vitro. Theriogenology 1998, 49, 441–449.

- Silva, J.R.; van den Hurk, R.; Costa, S.H.; Andrade, E.R.; Nunes, A.P.; Ferreira, F.V.; Lôbo, R.N.; Figueiredo, J.R. Survival and growth of goat primordial follicles after in vitro culture of ovarian cortical slices in media containing coconut water. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2004, 81, 273–286.

- Hovatta, O.; Silye, R.; Abir, R.; Krausz, T.; Winston, R.M. Extracellular matrix improves survival of both stored and fresh human primordial and primary ovarian follicles in long-term culture. Hum. Reprod. 1997, 12, 1032–1036.

- Hovatta, O.; Wright, C.; Krausz, T.; Hardy, K.; Winston, R.M. Human primordial, primary and secondary ovarian follicles in long-term culture: Effect of partial isolation. Hum. Reprod. 1999, 14, 2519–2524.

- Telfer, E.E.; McLaughlin, M.; Ding, C.; Thong, K.J. A two-step serum-free culture system supports development of human oocytes from primordial follicles in the presence of activin. Hum. Reprod. 2008, 23, 1151–1158.