Cocoyam [Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott] also known as taro is regarded as an important staple crop in the Pacific Islands, Asia and Africa.

- Colocasia esculenta

- cocoyam

- food security

- Africa

- exports

- imports

1. Introduction

Taro (Cocoyam) [Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott] is an important tropical root crop grown purposely for its starchy corms or underground stem [1]. It is regarded as one of the most important staple crops in the Pacific Islands, Asia and Africa [1][2][3][4]. It is one of the oldest world’s food crops believed to have been first domesticated in Southeast Asia before its eventual spread to other parts of the world [5][6]. The two most commonly cultivated species of Taro (Colocasia esculenta and Xanthosoma sagittifolium) belong to the Araceae family and are extensively cultivated in Africa.

Taro is an herbaceous monocotyledonous plant of 1–2 m height. The plant consists of central corm (below the soil surface) making the leaves grow upwards, roots grown downwards, while cormels, daughter corms and runners (stolons) grow laterally. The root system is fibrous and lies mainly at a depth of up to one meter of soil [3][7].

In most Pacific Island countries (PICs) where taro is widely cultivated and consumed, two species of Colocasia are recognized. They are C. esculenta var. esculenta, commonly called dasheen, and C. esculenta var. antiquorum, often referred to as eddoe [3][8]. The dasheen variety possesses large central corms, with suckers and/or stolons, while eddoes have somewhat small central corm and a large number of smaller cormels [3][9][10].

In Africa, Taro is commonly produced by smallholder, resource-limited and mostly female farmers [3]. Taro ranks third in importance, after cassava and yam, among the class of root and tuber crops cultivated and consumed in most African countries [3]. The crop is underutilized in the areas of export, human consumption, industrial uses, nutritional and other health benefits in Africa. Thus, the objective of this review is to provide a critical assessment of the leading players in the taro sub-sector globally and continentally with the most recent datasets useful for policy intervention and planning. Also, this study explores the nutritional, health and economic benefits of taro highlighting the role it can play in enhancing sustainable livelihoods especially in Africa.

2. Taro [Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott] in Africa

In many parts of the world, (especially, African countries), roots and tubers such as cassava (Manihot esculenta), sweet potato (Ipoemea batatas), yam (Dioscorea sp), and cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta and Xanthosoma sagittifolium), are important staple crops commonly cultivated by smallholder farmers and used as food security and income crops [11][12]. Taro production in Africa (especially SSA) is commonly by smallholder, resource-limited and mostly female farmers [3]. However, the crop is mostly referred to as “poor man’s crop” because its consumption is mainly by the low income households in the society [3]. As mentioned above, Africa contributed to over 70% of global taro production consistently in the past two decades and accounted for about 76 percent of world share in 2000 but, witnessed a slight decline in production levels in two decades attaining 72.27% (7.6 million tonnes) share of world total production in 2019 (Table 10) [11]. Despite the global recognition of taro production in Africa, the crop has suffered serious neglect, receiving little attention from agricultural researchers and government policymakers [3][13][12][14][15].

The world is faced with enormous task of providing sufficient food for over seven billion people, with 690 million people suffering from hunger globally, Africa region accounted for 73 million out of the 135 million people suffering from acute food insecurity in 2019 [16][17][18][19][20][21][22]. Hunger and malnutrition continue to escalate as the world’s food system is being threatened by the emergence of COVID-19 pandemic in December 2019. The attendant total and partial lockdowns in many countries has led to increased level of hunger and food insecurity. The situation in Africa is the one referred to as “a crisis within a crisis” with very high prevalence of hunger and malnutrition in most Africa countries. African governments need to intensify efforts in boosting agricultural production and keeping the food value chain active in order to stem the tide of hunger and food insecurity in the continent [23][24][25][26][27][28][29].

However, one of the means of reducing the level of hunger and protein-energy malnutrition in Africa (especially SSA) is through increased production and consumption of indigenous staples of high energy content such as taro [30][31]. Taro is recognized as a cheaper yam substitute, notably during period of food scarcity (hunger season) among many households in SSA (especially Ghana and Nigeria) and its production remained an integral part of many smallholder farming households in many parts of West and Central African countries [3]. It is worthy of note that, most of the output that placed Nigeria as number one taro producer globally and other high producing African countries like Cameroon, Ghana, Madagascar and Burundi (Figure 3) are carried out by smallholder rural farmers employing primitive technology and traditional farming practices with limited intensive management system [3][11]. Taro leaves and tubers possess excellent nutraceutical and healing properties. Thus, its increased production and consumption should be encouraged because of these properties in addition to its usefulness as a food security staple.

2.1. Recent Taro Productivity and Yield Potential in Africa

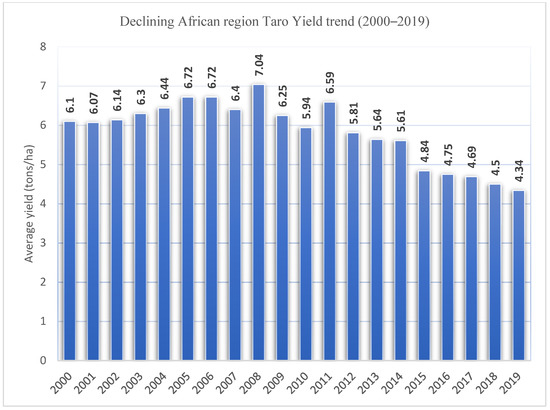

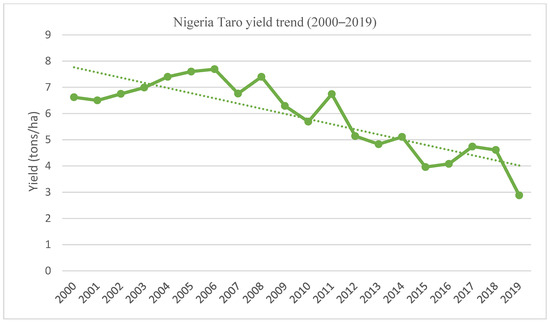

Total output of taro has witnessed significant increase in Africa, (mostly in West and Central Africa) where total production level in 2019 reached 7.62 million tonnes (the highest in 2 decades) (Table 1). However, these were largely due to increased harvested area rather than increase in yield per land area [11]. The average yield per land area (tons/ha) in Africa has consistently remained relatively low (Figure 4), from 6.10 tons/ha in 2000 to abysmally low 4.34 tons/ha in 2019 while Nigeria (Figure 5) the leading taro producer was not spared in the declining trend of taro yield per land area in Africa, decreasing from 6.62 tons/ha in 2000 to 2.88 tons/ha in 2019 [11]. Consequently, while other taro producing regions experienced significant increase in their yield per land area from 2000 to 2019, Africa recorded a monumental decrease in taro yield per land area in this period (Table 11 & Figure 4) [11]. African region recorded the lowest taro yield per land area in 2019 (Table 11) when compared with other regions such as Asia (16.50 tons/ha), America (10.41 tons/ha), and Oceania (8.73 tons/ha). This unprecedented yield difference in Africa is indicative of the fact that current yield of taro (cocoyam) in the region (especially West and Central Africa) is far below its potential yield. This could be attributed to the fact that taro production in Africa is largely with limited input and mostly cultivated on marginal lands. The culture of merely increasing production level through increased area of farmland is obviously unsustainable, because it resulted in high demand for available land.

Figure 4. Declining African region Taro (Cocoyam) yield with trend line (2000–2019), Source: Authors’ graph using data from FAOSTAT 2021 [11]. The vertical lines are the average of Taro and the horizontal axis represents the year of production.

Figure 5. Nigeria’s declining Taro yield with trend line (2000–2019); Source: Authors’ graph using data from FAOSTAT 2021 [11]. Note: The dotted line is the trend line; the solid line is the declining Nigeria Taro yield.

| Africa | America | Asia | Oceania | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Prod (1000 t) | Area Harvested (1000 ha) | Yield (t/ha) | Prod (tons) | Area Harvested (ha) | Yield (t/ha) | Prod (1000 t) | Area Harvested (ha) | Yield (t/ha) | Prod (tons) | Area Harvested (ha) | Yield (t/ha) |

| 2000 | 7435 | 1219 | 6.10 | 78,815 | 7621 | 10.34 | 1931 | 128,872 | 14.98 | 318,753 | 44,362 | 7.19 |

| 2001 | 7598 | 1251 | 6.07 | 81,871 | 8118 | 10.09 | 1947 | 139,676 | 15.01 | 321,062 | 45,321 | 7.08 |

| 2002 | 8112 | 1322 | 6.14 | 85,195 | 8571 | 9.94 | 1977 | 129,322 | 15.29 | 351,476 | 48,664 | 7.22 |

| 2003 | 8330 | 1322 | 6.30 | 82,214 | 8628 | 9.53 | 2026 | 133,626 | 15.16 | 361,416 | 50,192 | 7.20 |

| 2004 | 8557 | 1329 | 6.44 | 82,252 | 8669 | 9.49 | 1952 | 131,050 | 14.89 | 390,886 | 53,390 | 7.32 |

| 2005 | 9099 | 1354 | 6.72 | 82,994 | 8915 | 9.31 | 1914 | 127,935 | 14.96 | 413,900 | 55,658 | 7.44 |

| 2006 | 9510 | 1413 | 6.72 | 81,946 | 8731 | 9.39 | 1912 | 128,569 | 14.87 | 402,449 | 54,061 | 7.44 |

| 2007 | 9129 | 1426 | 6.40 | 80,343 | 7297 | 11.01 | 2014 | 129,513 | 15.55 | 395,889 | 52,735 | 7.51 |

| 2008 | 9617 | 1367 | 7.04 | 80,878 | 7227 | 11.19 | 2023 | 130,721 | 15.47 | 413,645 | 57,708 | 7.17 |

| 2009 | 7035 | 1125 | 6.25 | 81,350 | 7207 | 11.29 | 2082 | 133,211 | 15.63 | 412,859 | 54,574 | 7.57 |

| 2010 | 6904 | 1161 | 5.94 | 55,662 | 4883 | 11.40 | 2080 | 132,285 | 15.72 | 402,545 | 52,463 | 7.67 |

| 2011 | 6993 | 1062 | 6.59 | 46,999 | 3937 | 11.94 | 2074 | 131,868 | 15.72 | 421,634 | 54,973 | 7.67 |

| 2012 | 7196 | 1238 | 5.81 | 92,574 | 9884 | 9.37 | 2180 | 133,298 | 16.35 | 383,583 | 47,503 | 8.07 |

| 2013 | 6879 | 1219 | 5.64 | 103,142 | 10,638 | 9.70 | 2213 | 134,017 | 16.51 | 432,174 | 51,472 | 8.40 |

| 2014 | 7368 | 1312 | 5.61 | 101,393 | 8830 | 11.48 | 2388 | 147,551 | 16.18 | 417,198 | 51,031 | 8.18 |

| 2015 | 7366 | 1522 | 4.84 | 133,046 | 7785 | 17.09 | 2367 | 147,251 | 16.07 | 416,183 | 48,309 | 8.62 |

| 2016 | 7472 | 1574 | 4.75 | 74,274 | 7359 | 10.09 | 2440 | 152,588 | 15.99 | 392,197 | 46,725 | 8.39 |

| 2017 | 7646 | 1630 | 4.69 | 72,755 | 6930 | 10.50 | 2409 | 148,133 | 16.26 | 396,564 | 46,566 | 8.52 |

| 2018 | 7575 | 1682 | 4.50 | 43,865 | 4408 | 9.95 | 2438 | 148,380 | 16.43 | 403,122 | 46,595 | 8.65 |

| 2019 | 7619 | 1756 | 4.34 | 54,111 | 5200 | 10.41 | 2463 | 149,256 | 16.50 | 406,386 | 46,559 | 8.73 |

Source: Authors’ Compilation using data from FAOSTAT 2021 [11]; Note: t = Tonnes, ha = Hectare, Prod = Production.

Increased taro production is a worthwhile venture. There are industrial, nutraceutical and healing uses for the crop both within and outside any of the producing countries. Exporting taro to other countries will boost the revenue base of the producing countries; livelihoods of the smallholder farmers and other actors along the value chain would also be enhanced.

2.2. Taro Trade Potentials in Africa

The unprecedented increase in total output of taro in Africa (especially, West and Central Africa) in the last two decades indicated that there could be further increase in another decade to come. The estimate from Tridge [32] in 2018 indicated that China (with export value of $417.18 million) remained the number one exporter of taro, followed by Mexico ($264.49 million), USA ($161.01 million) and Canada ($141.96 million) (Figure 1). However, no top taro producing countries from sub-Saharan Africa, which accounted for over 70% of global share of taro production in two decades (2000–2019), was listed among the top 20 cocoyam exporting countries (Figure 1). This may be due to the difficulty in obtaining consistent and reliable data on taro import and export for most African countries. Although 65% of the global taro production is accounted for by Africa in 2019 [11], there is insufficient information on the contribution of taro from these top producing countries to the international taro market. Apart from poor data on trade in taro in Africa, it could also be due to the fact that taro production in SSA is mainly for meeting local needs for food security [3].

In 2018, the three major importers of taro are USA ($768.68 million), Japan ($227.10 million) and United Kingdom ($157.17 million) (Figure 3). Like taro exports, no top producing African countries was listed among the top 20 importers of taro in 2018. There is enormous trade potentials for taro markets in Africa both within (between countries in Africa) and outside the region. There is urgent need to improve taro production and marketing structures in Africa in order to maximize of its gains for economic empowerment [3][32].

2.3. Challenges of Taro in Africa

The non-existent of effective research and policy interventions for the increased production and marketing (international trade) of taro in most African countries (especially SSA) has left the crop as an unpopular and under-utilized root and tuber crop when compared with other root and tuber crops such as cassava, yam and potato. The consistent increase in production levels (although with increasing reduction in yield per land area—Figure 4) of taro in most high producing Africa countries (Nigeria, Cameroon and Ghana) has not attracted the international market for more than three decades [3][6][33][34]. Taro production in most major African growing areas has remained at subsistence level with farmers depending mainly on traditional farming inputs [3][26][27][28].

To further worsen the challenges of taro production, consumption and commercialization in Africa, is the emergence of taro leaf blight (TLB) (Phytophthora colocasiae) in West Africa in 2009 [3][34]. The outbreak of TLB was opined to have accounted for more than US$1.4 billion economic loss annually with enormous impact on the genetic erosion of gene pool in the region [3]. Taro production is facing continuous decline due to rapid prevalence of TLB. This has resulted in continuous low yield, poor quality corms and reduced commercialization in most taro producing countries [3][35].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13084483

References

- Si, H.; Zhang, N.; Tang, X.; Yang, J.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhou, X. Transgenic Research in Tuber and Root Crops. Genet. Eng. Hortic. Crop. 2018, 225–248.

- Kreike, C.M.; Van Eck, H.J.; Lebot, V. Genetic diversity of taro, Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott, in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2004, 109, 761–768.

- Onyeka, J. Status of Cocoyam (Colocasia esculenta and Xanthosoma spp) in West and Central Africa: Production, Household Importance and the Threat from Leaf Blight; CGIAR Research Program on Roots, Tubers and Bananas (RTB): Lima, Peru, 2014; Available online: (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Aguegui, A.; Fatokun, C.A.; Haln, S.K. Protein analysis of ten cocoyam, Xanthosoma sagittifolium (L). Schott and Colocasia esculenta (L.) Schott genotypes. In Root Crops for Food Security in Africa, Proceedings of the 5th Triennial Symposium; International Society for Tropical Roots Crops-Africa Branch (ISTRC-AB): Kampala, Uganda, 1992; p. 348.

- Ramanatha, R.V.; Matthews, P.J.; Eyzaguirre, P.B.; Hunter, D. (Eds.) The Global Diversity of Taro: Ethnobotany and Conservation; Bioversity International: Rome, Italy, 2010.

- Ubalua, A.O.; Ewa, F.; Okeagu, O.D. Potentials and challenges of sustainable taro (Colocasia esculenta) production in Nigeria. J. Appl. Biol. Biotechnol. 2016, 4, 053–059.

- Onwueme, I.C. Tropical Root and Tuber Crops—Production, Perspectives and Future Prospects; FAO Plant Production & Protection Paper 126; FAO: Rome, Italy, 1994.

- Lebot, V. Biomolecular evidence for plant domestication in Sahul. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 1999, 46, 619–628.

- Wagner, W.L.; Herbst, D.R.; Sohmer, S.H. Manual of the Flowering Plants of Hawaii; Revised Edition; University of Hawaii Press/Bishop Museum Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 1999.

- Purseglove, J.W. Tropical Crops. Monocotyledons; Longman: London, UK, 1972.

- FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations Statistical Database; Statistical Division; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2021; Available online: (accessed on 5 February 2021).

- Owusu-Darko, P.G.; Paterson, A.; Omenyo, E.L. Cocoyam (corms and cormels)—An underexploited food and feed resource. J. Agric. Chem. Environ. 2014, 3, 22–29.

- Rashmi, D.R.; Raghu, N.; Gopenath, T.S.; Pradeep, P.; Bakthavatchalam, P.; Karthikeyan, M.; Gnanasekaran, A.; Ranjith, M.S.; Chandrashekrapp, G.K.; Basalingappa, K.B. Taro (Colocasia esculenta): An Overview. J. Med. Plants Stud. 2018, 6, 156–161.

- Chukwu, G.O. Euology for Nigeria’s giant crop. Adv. Agric. Sci. Eng. Res. 2011, 1, 9–13.

- Chukwu, G.O.; Okoye, B.C.; Agugo, B.A.; Amadi, C.O.; Madu, T.U. Cocoyam Rebirth: A Structural Transformation Strategy to Drive Cocoyam Value Chain in Nigeria. In (ASURI, NRCRI Book of Readings) Structural Transformation in Root and Tuber Research for Value Chain Development and Employment Generation in Nigeria; ASURI, NRCRI: Umudike, Nigeria, 2017; pp. 216–227.

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. In Transforming Food Systems for Affordable Healthy Diets; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020.

- Food Security Information Network (FSIN). 2020 Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC 2020). 2020. Available online: (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Ayinde, I.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Akinbode, S.O.; Otekunrin, O.A. Food Security in Nigeria: Impetus for Growth and Development. J. Agric. Econ. 2020, 6, 808–820.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. Healthy and Sustainable Diets: Implications for Achieving SDG2. In Zero Hunger. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–17.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Sawicka, B.; Ayinde, I.A. Three decades of fighting against hunger in Africa: Progress, challenges and opportunities. World Nutr. 2020, 11, 86–111.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Momoh, S.; Ayinde, I.A. How far has Africa gone in achieving the Zero Hunger Target? Evidence from Nigeria. Glob. Food Secur. 2019, 22, 1–12.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Momoh, S.; Ayinde, I.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. How far has Africa gone in achieving the Sustainable Development Goals? Exploring the African dataset. Data Brief 2019, 27, 1–7.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Fasina, F.O.; Omotayo, A.O.; Akram, M. Assessing the zero hunger target readiness in Africa in the face of COVID-19 pandemic. Caraka Tani J. Sustain. Agric. 2020, 35, 213–227.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Ogodo, A.C.; Fasina, F.O.; Akram, M.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Egbuna, C. Coronavirus Disease in Africa: Why the Recent Spike in Cases of COVID-19? In Coronavirus Drug Discovery: SARS-Cov-2 (COVID-19) Impact, Pathogenesis, Pharmacology and Treatment 2020; in press.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Momoh, S.; Ayinde, A.I. Assessing the Zero Hunger Target Readiness in Africa: Global Hunger Index (GHI) patterns and Indicators. In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual National Conference of the Farm Management Association of Nigeria (FAMAN), Abeokuta, Nigeria, 7–10 October 2019; pp. 456–464.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Fasina, F.O.; Omotayo, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A.; Akram, M. COVID-19 in Nigeria: Why continuous spike in cases? Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2021, 14, 1–4.

- Kalu, B. COVID-19 in Nigeria: A disease of hunger. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 556–557.

- Cucinotta, D.; Vanelli, M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Med. Atenei Parm. 2020, 91, 157–160.

- Otekunrin, O.A.; Otekunrin, O.A. COVID-19 and Hunger in Africa: A crisis within a crisis. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Food Science and Technology, Vienna, Austria, 16–17 October 2020; pp. 27–28.

- Ogundahunsi, G.A. Estimation of Digestive Energy of Cocoyam Foods: (i) Roasted (ii) Peeled and Boiled (iii) Peeled, Ground and Steamed. Master’s Thesis, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria, 1981; 105p.

- Agbelemoge, A. Utilization of cocoyam in rural households in South Western Nigeria. Afr. J. Food Agric. Nutr. Dev. 2013, 13, 7944–7956.

- Tridge. 2020. Available online: (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Boakye, A.A.; Wireko-Manu, F.D.; Oduro, I.; Ellis, W.O.; Gudjónsdóttir, M.; Chronakis, I.O. Utilizing cocoyam (Xanthosoma sagittifolium) for food and nutrition security: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2018, 6, 703–713.

- Acheampong, P.; Osei-adu, J.; Amengo, E.; Sagoe, R. Cocoyam Value Chain and Benchmark Study in Ghana; CSIR: Accra, Ghana, 2015.

- Mbong, G.A.; Fokunang, C.N.; Fontem, L.A.; Bambot, M.B.; Tembe, E.A. An overview of Phytophthora colocasiae of cocoyams: A potential economic disease of food security in Cameroon. Discourse J. Agric. Food Sci. 2013, 1, 140–145.