Paroxysmal movement disorders (PMDs) are rare neurological diseases typically manifesting with intermittent attacks of abnormal involuntary movements. Two main categories of PMDs are recognized based on the phenomenology: Paroxysmal dyskinesias (PxDs) are characterized by transient episodes hyperkinetic movement disorders, while attacks of cerebellar dysfunction are the hallmark of episodic ataxias (EAs). From an etiological point of view, both primary (genetic) and secondary (acquired) causes of PMDs are known. Recognition and diagnosis of PMDs is based on personal and familial medical history, physical examination, detailed reconstruction of ictal phenomenology, neuroimaging, and genetic analysis. Neurophysiological or laboratory tests are reserved for selected cases. Genetic knowledge of PMDs has been largely incremented by the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies. The wide number of genes involved in the pathogenesis of PMDs reflects a high complexity of molecular bases of neurotransmission in cerebellar and basal ganglia circuits. In consideration of the broad genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity, a NGS approach by targeted panel for movement disorders, clinical or whole exome sequencing should be preferred, whenever possible, to a single gene approach, in order to increase diagnostic rate. This review is focused on clinical and genetic features of PMDs with the aim to (1) help clinicians to recognize, diagnose and treat patients with PMDs as well as to (2) provide an overview of genes and molecular mechanisms underlying these intriguing neurogenetic disorders.

- hyperkinetic movement disorders

- dyskinesia

- ataxia

- cerebellum

- basal ganglia

- therapy

- acetazolamide

- epilepsy

- whole exome sequencing

- functional movement disorders

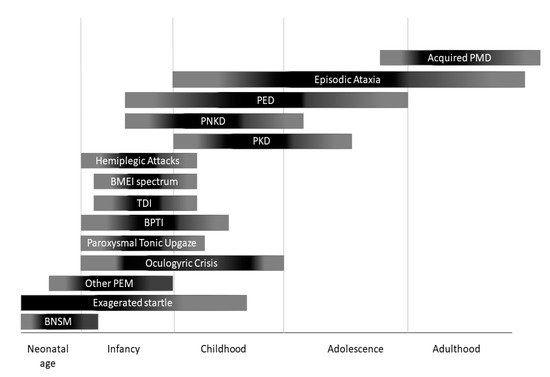

Paroxysmal movement disorders (PMDs) are rare neurological diseases typically manifesting with intermittent attacks of abnormal involuntary movements[1]. The term “paroxysmal” indicates a well-defined onset and termination of clinical manifestations. Two main categories of PMDs are recognized based on phenomenology: Paroxysmal dyskinesias (PxDs) are characterized by transient episodes hyperkinetic movement disorders, while attacks of cerebellar dysfunction are the hallmark of episodic ataxias (EAs)[2]. From an etiological point of view, both primary (genetic) and secondary (acquired) causes of PMDs are recognized. Some aspects of clinical history may help to distinguish primary from secondary PMDs: Most primary forms occur as sporadic or familial cases with autosomal dominant inheritance, and most often onset of manifestations is set in childhood or adolescence (Figure 1), and interictal neurological examination is unremarkable; secondary forms occur sporadically, more usually begin after the second decade of life (Figure 1), and clinical examination is frequently abnormal also outside of attacks.

Figure 1. Onset of different paroxysmal movement disorders (PMDs) according with age. BNSM: benign neonatal sleep myoclonus; BMEI: benign myoclonus of early infancy; BPTI: Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy; PEM: paroxysmal eye movements; PED: paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesia; PKD: paroxysmal kynesigenic dyskinesia; PNKD: paroxysmal non-kynesigenic dyskinesia.

A further category that may manifest as PMDs are functional (psychogenic) movement disorders (FMDs). Patients with FMDs may show tremor, dystonia, myoclonus, parkinsonism, speech and gait disturbances, or other movement disorders whose patterns are usually incongruent with that observed in organic diseases, although sometimes diagnosis may be challenging. Diagnosis of FMDs is based on positive clinical features (e.g., variability, inconsistency, suggestibility, distractibility, and suppressibility) during physical examination and should be considered in presence of some clues such as intra-individual variability of phenomenology, duration and frequency of attacks, and/or precipitation of the disorder by physical or emotional life events. Other supporting information can be helpful (i.e., neurophysiologic and imaging studies)[3].

Recognition and diagnosis of PMDs are based on personal and familial medical history, physical examination, detailed reconstruction of ictal phenomenology (possibly including video-recording of at least one attack), brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and genetic analysis. Neurophysiological (i.e., standard electroencephalogram or long-term monitoring) or laboratory tests are reserved for cases in which an epileptic origin of the attack cannot be excluded, or brain MRI reveals alterations that are compatible with genetic-metabolic or secondary causes. Genetic knowledge of PMDs has been largely incremented by the advent of next generation sequencing (NGS) methodologies, which allowed to increase both molecular diagnosis and identification of ultra-rare or new genes. The wide number of genes involved in the pathogenesis of PMDs (Table 1) reflects a high complexity of molecular bases of neurotransmission in cerebellar and basal ganglia circuits (Figures 2–4). This comprehensive review is focused on clinical and genetic features of PMDs according to current nosology (Table 2). As this review is mainly targeted on genetic causes of PMDs, functional PMDs will not be discussed further.

Table 1. Main genetic causes of paroxysmal movement disorders. A question mark follows treatment options that: have been proposed basing on pathophysiological assumptions, are under investigation or have been shown to be beneficial only in single-case reports.

|

Gene |

OMIM |

Inheritance |

Age at onset |

PMDs subtype |

Attack duration |

Isolated versus |

Allelic disorders |

Other possible features |

MRI |

Treatment |

|

PRRT2 |

614386 |

AD |

<18 years |

PKD |

Very brief (<1 |

I/C |

BFIS, ICCA, |

|

Normal |

CBZ (PKD) ACZM (EA) |

|

PNKD |

609023 |

AD |

<18 years |

PNKD |

Long (>1 |

I |

Migraine |

|

|

BDZ (Attacks relief) |

|

SLC2A1 (GLUT-1) |

138140 |

AD |

Variable |

PED, EA, HA, PEM |

Intermediate |

I/C |

Classic GLUT1-DS, HSP, |

Anaemia, |

|

Ketogenic diet, triheptanoin |

|

PDH complex (PDHA1/PDHX /DLAT) |

300502/608769/608770 |

AR |

Infancy |

PED/PNKD |

Variable |

I/C |

Leigh |

Developmantal delay/ID, Seizures, progressive dystonia |

Pallidal hyperintensities, Callosal agenesis |

Ketogenic diet |

|

ECHS1 |

602292 |

AR |

Infancy |

PED |

Variable |

I/C |

|

Leigh |

From Pallidal hyperintensities to Leigh-like abnormalities |

Valine-restricted diet? detoxifying drugs? |

|

HIBCH |

610690 |

AR |

Infancy |

PED |

Variable |

I/C |

Leigh |

ID, Seizures, progressive dystonia |

From Pallidal hyperintensities to Leigh-like abnormalities |

Valine-restricted diet? detoxifying drugs? |

|

ATP1A3 |

182350 |

AD |

Variable |

PNKD ([hemi]dystonic attacks), HA, PEM |

Variable |

C |

EIEE, AHC, CAPOS, RECA, RDP |

Seizures, dysautonomic paroxysms, nonparoxysmal |

|

Flunarizine (HA prophylaxis), BDZ (HA relief) |

|

ADCY5 |

600293 |

AD |

Variable |

PKD/PNKD/PED/PND |

Brief |

C |

PNKD |

Axial |

|

Caffeine? |

|

TBC1D24 |

613577 |

AR |

Childhood |

PED |

Variable |

C |

Deafness, DOORS syndrome, Rolandic Epilepsy, EIEE16, Myoclonic epilepsy |

Sizures, Developmental delay/ID, myoclonus, ataxia, extraneurological abnormalities |

|

|

|

SLC16A2 (MCT8) |

300095 |

X linked |

<1–2 months |

PKD (triggered by passive movements) |

Very brief |

C |

|

Mental |

|

TRIAC? |

|

SCN8A |

600702 |

AD |

Infancy |

PKD |

Brief |

C |

Epilepsy |

Mental |

|

CBZ, oxcarbazepine |

|

KCNMA1 |

600150 |

AD |

Childhood |

PNKD |

Long (>1 |

C |

|

epilepsy, developmental delay, progressive HSP, ataxia |

|

|

|

GCH1 |

600225 |

AD |

<18 years |

PED |

Variable |

I/C |

DRD |

Non paroxysmal dystonia and parkinsonism |

|

L-DOPA |

|

PDE10A |

610652 |

AR/AD |

Childhood |

PNKD |

NR |

C |

Chorea without paroxysms |

Dystonia, Parkinsonism, marked fluctuations |

Striatal hyperintensities (in AD cases) |

|

|

KCNA1 |

176260 |

AD |

Childhood (2–15) |

EA1 |

Minutes |

I |

EIEE, PKD, EDE (AR) |

interictal Myokymia; progressive ataxia (20%), epilepsy (10%) |

Normal ore cerebellar atrophy (10%) |

CBZ, PHT, ACZM |

|

CACNA1A |

601011 |

AD |

Childhood (0–20) |

EA2/PTU/BPT |

Variable |

I/C |

FHM1, SCA6, CA |

progressive ataxia, Developmental delay |

Normal or cerebellar atrophy |

ACZM, 4-APD, LEV |

|

CACNB4 |

601949 |

AD |

Young-adult onset |

EA5 |

several hours |

I |

JME, IGE, CND (AR) |

Epilepsy, permanent ataxia |

Normal |

ACZM |

|

SLC1A3 (EAAT1) |

600111 |

AD |

infancy or childhood (rarely adulthood) |

EA6 |

several hours |

I |

Adult-onset progressive ataxia |

Seizures (rare) |

Nornmal; rarely cerebellar atrophy |

ACZM |

|

UBR4 |

609890 |

AD |

around age 2 years |

EA8 |

minutes to hours |

I |

|

nystagmus, myokymia, tremor |

|

Clonazepam |

|

FGF14 |

601515 |

AD |

late-childhood to early adulthood |

EA9 |

minutes |

I/C |

SCA27, CA |

progressive ataxia, nystagmus, postural upper limb tremor, ID |

|

|

|

BCKD Complex |

608348/248611 |

AR |

Variable |

EA/PNKD |

Minutes to hours |

C |

Classic MSUD |

developmental delay, progressive psychomotor retardation, seizures, ataxia, |

T2 hypersignal in in the brainstem, globus pallidus, thalami, and dentate nuclei |

BCAA restricted diet |

|

KCNA2 |

176262 |

AD |

Infancy or childhood |

EA |

Seconds to hours |

C |

EIEE32, SCA, PME |

Epilepsy |

|

ACZM (variable) |

|

SCN2A |

182390 |

AD |

infancy or childhood |

EA |

minutes to days |

C |

EIEE11, BFIS3 |

Seizures +/- encephalopathy, developmental delay/ID |

Normal or cerebellar atrophy |

ACZM (variable) |

4-APD: 4-amynopiridine; ACZM: acetazolamide; AHC: alternating hemiplegia of childhood; AR: autosomic recessive; AD autosomic dominant; BDZ: benzodiazepines; BFIS: benign familial infantile seizures; BPTI: Benign paroxysmal torticollis of infancy; C. Combined; CA: congenital ataxia; CAPOS: cerebellar ataxia, pes cavus, optic atrophy, sensorineural hearing loss; CBZ: carbamazepine; CND: complex neurodevelopmental disorder; DOORS: deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, mental retardation, and seizures; DRD: Dopa-Responsive Dystonia EA: episodic ataxia; EDE: epileptic dyskinetic encephalopathy; EIEE: early infantile epileptic encephalopathy; FHM: familiar hemiplegic migraine; HA: hemiplegic attacks; I: Isolated; ID: Intellectual disability; JME: juvenile myoclonic epilepsy; LEV: levetiracetam; MSUD: maple syrup urine disease; PED: paroxysmal exercise-induced dyskinesia; PEM: paroxysmal eye movements; PHT: phenytoin; PKD: paroxysmal kynesigenic dyskinesia; PNKD: paroxysmal non-kynesigenic dyskinesia; PME: progressive myoclonic epilepsy; PTU: paroxysmal tonic upgaze, RECA: recurrent encephalopathy with cerebellar ataxia; RDP: rapid onset dystonia-parkinsonism; SCA: spinocerebellar ataxia; VPA: Valproic Acid.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms21103603

References

- Roberto Erro; Kailash P. Bhatia; Unravelling of the paroxysmal dyskinesias. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 2018, 90, 227-234, 10.1136/jnnp-2018-318932.

- Aurélie Méneret Md; E. Roze; Paroxysmal movement disorders: An update. Revue Neurologique 2016, 172, 433-445, 10.1016/j.neurol.2016.07.005.

- Mary Ann Thenganatt; Joseph Jankovic; Psychogenic (Functional) Movement Disorders. CONTINUUM: Lifelong Learning in Neurology 2019, 25, 1121-1140, 10.1212/con.0000000000000755.