Thirty to fifty percent of hepatocellular carcinomas (HCC) display an immune class genetic signature. In this type of tumor, HCC-specific CD8 T cells carry out a key role in HCC control. Those potential reactive HCC-specific CD8 T cells recognize either HCC immunogenic neoantigens or aberrantly expressed host’s antigens, but they become progressively exhausted or deleted. These cells express the negative immunoregulatory checkpoint programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) which impairs T cell receptor signaling by blocking the CD28 positive co-stimulatory signal. The pool of CD8 cells sensitive to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 treatment is the PD-1dim memory-like precursor pool that gives rise to the effector subset involved in HCC control.

- hepatocellular carcinoma

- immunotherapy

- PD-1

- PD-L1

- immune check-point inhibitor

- combination therapy

- CD8 T cell response

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and has an incidence of approximately 850,000 new cases per year. HCC accounts for approximately 90% of malignant liver tumors and is one of the most aggressive types of cancer, with few and unsatisfactory therapeutic options [1]. Since current therapies are limited and recurrence of HCC is common in patients treated with the standard therapeutic arsenal, immunotherapy presents itself as a promising possible response to the real need for new treatments [2]. The new emergence of treatments based on the modulation of inhibitory immune checkpoint (IC) opens new opportunities for the control of hepatocarcinoma [3,4,5]. Blockade of the programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD-ligand(L)1 pathway is the paradigm of this type of treatment to counteract T cell response exhaustion [6,7], but we still do not have predictive variables to forecast a favorable response, and in many cases the initial response disappears [8,9]. The HCC-specific CD8 T cell response can be essential in HCC control due to its ability to recognize tumor cells and destroy them by cytolytic and no cytolytic mechanisms [10]. Nevertheless, these cells become exhausted during cancer progression [11,12] but can be temporally restored by immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). To enhance and extend the effect of this approach, the synergy of this therapy with other strategies acting at different levels (blocking other negative ICs, triggering positive co-stimulatory pathways, blocking vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway, reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism, or adding loco-regional therapies) is being explored [13]. This work revises the types of HCC potentially sensitive to immunotherapy, the role of PD-1 expressing CD8 T cells in HCC treatment, the target population for CD8 T cell immunotherapy and the effect of PD-1 based treatment combinations on the restauration of HCC-specific cytotoxic T cell response.

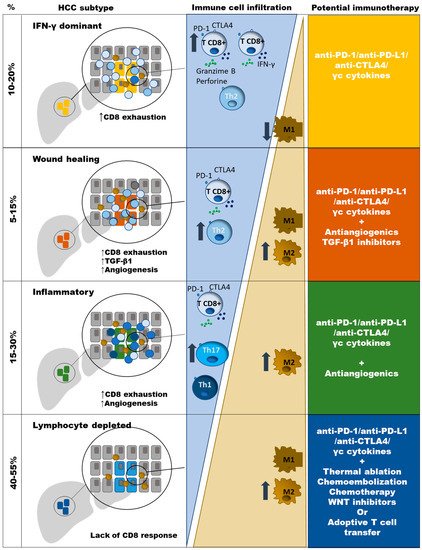

2. Types of HCC According to Potential Sensitivity to PD-1 Based Immunotherapy

3. Role of PD-1-Expressing HCC-Specific CD8 T Cell Response in HCC Control

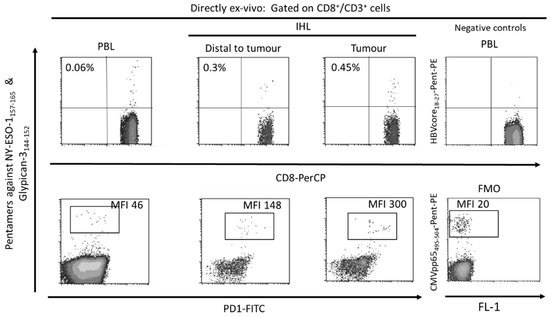

The tumor-associated antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response is essential for the control of solid tumors due to their ability to recognize tumor cells and to destroy them [40,41]. Exhausted CD8+ T cells are the main subset of TILs that perform anti-tumor effector functions [10,42]. Specifically, in HCC it is possible to find a high number of T cells infiltrating the tumor (Figure 2) and there is a correlation between the density of infiltrating lymphocytes and the prognosis of the disease [43]. Furthermore, after loco-regional treatment of HCC, a longer survival has been observed in those subjects in whom a specific CD8+ T response against HCC associated antigens is detected [44]. Therefore, large numbers of CD8+ TILs in HCC correlate with improved OS, longer relapse-free survival, and diminished disease progression [10,45,46]. HCC associated antigens comprise a heterogeneous set of autologous proteins that are rendered immunogenic in tumors by mutation [35] or aberrant expression [10,47] (Figure 2). The development of an effector cytotoxic T cell immune response against these antigens may provide a barrier to tumor progression. Nevertheless, most of the T cells targeting autologous aberrantly expressed epitopes are deleted or in a tolerogenic state [33,48], although some studies have shown a positive effect after PD-1 blockade in T cells targeting these kind of antigens [7]. Anyhow, the response to ICI could be more effective in T cells targeting HCC neo-antigens. A previous study has suggested that searching for host’s human leukocyte antigen (HLA) restricted tumoral neoantigens will permit to find T cells that after the appropriate treatment will exert tumor control [35]. HCC will commit mutations that will give rise to new epitopes that will be recognized as exogen antigens by T cells. Unfortunately, these cells will become exhausted during HCC progression, not being able to keep the tumor under control. These exhausted CD8+ T cells show a gene signature that is completely different from those of memory and effector T cells [49,50,51]. During the exhaustion process, T cell response progressively loses the effector functions and finally undergoes apoptosis [11,52]. The exhausted CD8 T cells are featured by the expression of different inhibitory IC, such as PD-1, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4), T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain (Tim3), and lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG3) that can be modulated to rescue T cell reactivity [21,53]. The ligands of these IC are expressed by resident liver cells. In fact, PD-L1 is expressed on hepatocytes [22], hepatic stellate cells [54], liver sinusoidal endothelial cell (LSEC) [55], and Kupffer cells [56,57], while PD-L2 expression is restricted to dendritic cells [58]. PD-1 and PD-L1 upregulation promotes CD8+ T-cell apoptosis and postoperative recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients [59]. The in-vitro treatment of these T cells with antibodies against these myriad of inhibitory IC increases T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion.

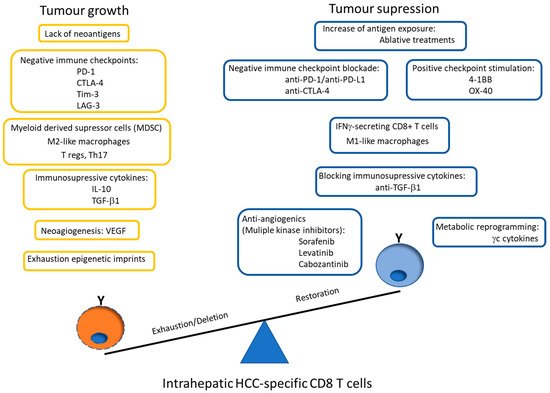

Nevertheless, these exhausted CD8+ cells develop epigenetic imprints that steadily maintain the functional impairment, which is transmitted to the progeny, making temporary the effects of immunomodulatory treatments [49]. Even in the context of a PD-1 knockdown HCC-specific CD8 T cell model, although a tumor killing enhancement is initially observed, this effect is limited by compensatory engagement of alternative co-inhibitory and senescence programs upon repetitive antigen stimulation [60]. These epigenetic imprints induce the expression of specific transcription factors, such as the thymocyte selection-associated high mobility group box protein (TOX) that is up-regulated on CD8+ T cells in HCC and promotes their exhaustion by regulating endocytic recycling of PD-1 [61]. Additionally, the up-regulation of the ligands of these negative IC is induced in the HCC microenvironment. The regulation of PD-L1 expression could be related with the level of M2 macrophages that are recruited by the tumor cell-intrinsic osteopontin secretion. In HCC animal models, the level of M2 macrophages decreases after osteopintin blockade, which correlates with an increased CD8 effector response to PD-L1 blockade [62]. M2-like macrophages favor an immunosuppressive landscape by depleting CD8 T cells and inducing CD4+ T regulatory cells (Tregs) [63]. Additionally, M1 macrophages can induce PD-L1 expression on hepatocarcinoma cells by IL-1β effect [64]. These data suggest an important role of macrophages in modulating CD8 T cell exhaustion in HCC by promoting a immunotolerant environment [65] and by up-regulating themselves both PD-L1 and PD-L2 expression [66]. However, PD-L1 expression on macrophages could also have a positive input because it correlates with CD8 T cell infiltration and increased OS after treatment [67], probably in the case of M1-like macrophage infiltration [17]. Moreover, HCC-specific CD8 T cell itself induces PD-L1 up-regulation on hepatocytes, linked to a subsequent impairment of IFN-γ secretion by T cells [68]. There is a gradient of PD-1 expression on intra-tumoral CD8+ cells, which probably defines the progenitor (PD-1dim) and effector (PD-1high) pools [69]. The PD-1high population can co-express positive co-stimulatory checkpoints, such as 4-1BB, that can be triggered to rescue these cells from exhaustion [70,71]. Nevertheless, to target the PD-1dim subset could be more operative to get a more efficient response to ICI. The PD-1 level of the intrahepatic resident CD8+ cells inversely correlates with the expression of the transcription factor T-bet [72], which has been correlated with a late dysfunctional phenotype in the PD-1high pool, since the effector late dysfunctional pool expresses the transcription factor Eomes and loses T-bet expression [73]. On the contrary, PD-1dim expression is a marker of the progenitor pool, which is the subset that provides the proliferative burst after anti-PD-1 treatment [69]. Therefore, T cell restoration should focus on PD-1dim CD8+ T cells. In order to improve both the precursor and the effector pools, searching for PD-1/PD-L1 based combinatory therapies, such as modulation of suppressive soluble mediators (interleukin (IL)-10, IL-17, TGF-β1), blocking suppressive cells (Tregs, myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSC), M2 tumor associated macrophages (TAM)), triggering positive co-stimulation (tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9, 4-1BB), mitochondrial metabolic reprogramming, impairing neo-angiogenesis, inducing expression of HCC neo-antigens or epigenetic modulation by gamma-chain (γc) cytokines [11,12,14,74] could improve the response to PD-1/PD-L1 blocking monotherapy. Figure 3 summarizes the potential mechanisms involved in HCC-specific CD8 T cell impairment.

Figure 3. Scheme showing the potential mechanisms involved in HCC-specific CD8 T cell impairment. The graph also highlights the possible PD-1/PD-L1 blockade-based combination therapies to rescue effector and precursor HCC-specific cytotoxic T cell response. PD-1: programmed cell death protein 1, CTLA-4: cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4, Tim-3: T cell immunoglobulin domain and mucin domain, LAG-3: lymphocyte-activation gene 3, T regs: CD4 T regulatory cells, Th: T helper, IL: interleukin, TFG: tumor growth factor, VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor, 4-1BB: tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 9, OX-40: Tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 4, γc: gamma-chain.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13081922