Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the deadliest cancer. Clinical guidelines for the management of HCC endorse algorithms deriving from clinical variables whose performances to prognosticate HCC is limited. Liquid biopsy is the molecular analysis of tumor by-products released into the bloodstream. It offers minimally-invasive access to circulating analytes like DNA, RNA, exosomes and cells. This technology demonstrated promising results for various applications in cancers, including prognostication.

- liver cancer

- biomarkers

- precision medicine

- circulating

- prognosis

1. Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) shows a worrisome epidemiological trajectory [1]. The WHO predicts over 1 million HCC-related deaths in 2030 [2]. A particular feature of HCC is that it typically arises on a chronically damaged organ, mostly cirrhosis, for which viral hepatitis, alcohol use disorder and NAFLD are common causes. This facilitates the identification of patients at risk and has enabled successful surveillance programs for early cancer detection. However, having two potentially life-threatening diseases in the same patient (i.e., HCC and cirrhosis) complicates its clinical management and prognosis prediction. Numerous attempts have been pursued to reliably prognosticate HCC, using various strategies. The most widely used classifications, like the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) algorithm [3,4], relies on clinical variables. Other approaches investigate the contribution of tumor markers like α-fetoprotein (AFP) [5] and molecular markers derived from the tumor or adjacent non-tumor samples [6,7,8,9]. Regardless of the strategy, the prognostic performance of these algorithms needs to be improved. Following a ‘precision medicine’ perspective may be a way of improving HCC prognostication. This implies access to genomic data on a patient-basis, which requires biopsy or surgical specimens for tissue samples of the tumor. This is particularly difficult in HCC for which, unlike most solid tumors, diagnosis mostly relies on imaging and tissues samples are rarely available [10,11]. In addition, tissue biopsies are associated with potential complications and should not be sequentially repeated [12].

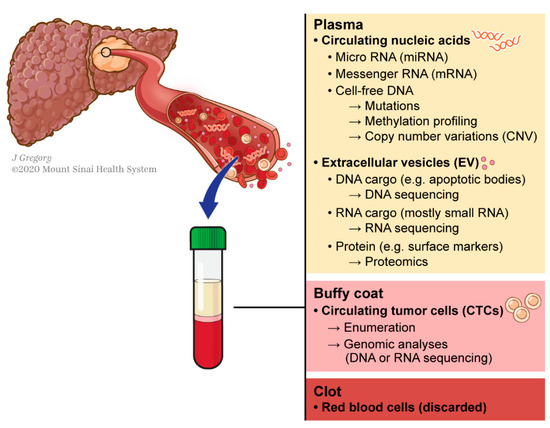

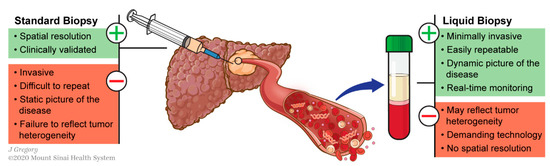

This can be circumvented using liquid biopsy, which refers to the molecular analysis of tumor components released from a solid tumor into biological fluids like blood. These analytes include circulating tumor nucleic acids (DNA and RNAs), cells (CTCs) and exosomes (Figure 1). This technology has shown promising results for various applications in the management of different types of cancers including HCC [13,14,15]: early diagnosis [16,17], detection of minimal residual disease [18], decision-making for systemic therapies [19,20] or even to decipher complex biological traits of cancers [21,22,23,24]. This technology offers a valuable alternative to standard biopsy. Tissue biopsy is indeed invasive and associated with potential risks such as pain, bleeding or even seeding of the cancer (PMID: 18669577). Conversely to standard biopsy, liquid biopsy displays the advantages of being easily repeatable and can thereby help for monitoring, providing a dynamic picture of the disease course. In addition, it may reflect different regions of the tumor and thus recapitulate eventual intra-tumoral heterogeneity (ITH) (Figure 2) [25].

2. Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

DNA fragments are released from solid tumors into the bloodstream via active and passive mechanisms. The latter seems to predominate, being partially driven by cell necrosis and apoptosis [26]. This occurs at any tumor stage and offers minimally-invasive access to key molecular information of the tumor including genomic (copy number variations (CNV) or point mutations) as well as epigenetic (DNA methylations changes) data. Numerous studies show the value of ctDNA as a polyvalent biomarker in cancer. For example, ctDNA allowed detection of minimal residual disease (MRD) in a prospective cohort of 230 patients undergoing surgical resection of stage II colon cancer. Postoperative detection of ctDNA outperformed prognostic factors such as TNM stage, for the prediction of recurrence-free survival [18].

In HCC, a pilot study demonstrated that detection of mutations in the plasma of HCC patients was feasible and recapitulated the ones detected in tumor tissue [27]. Table 1 summarizes reports investigating ctDNA in HCC prognostication.

Table 1. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA).

|

Number of Patients |

Treatment |

Biomarkers |

Technique |

Main Finding |

[Ref.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

CNV |

|||||

|

34 HCC |

Surgery |

ctDNA (harboring SNV or CNV) |

Targeted-sequencing and low coverage whole-genome sequencing |

ctDNA can detect minimal residual disease (MRD) and predict survival |

[28] |

|

151 HCC; 14 healthy controls |

Sorafenib |

VEGFA amplification |

Whole-genome sequencing |

High concentration of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was associated with poor outcomes but VEGFA ratio was not a prognostic factor. |

[29] |

|

Mutations |

|||||

|

46 HCC |

Surgery Transplant |

ctDNA |

Targeted-sequencing and exome-sequencing |

Detection of ctDNA was associated with increased recurrence |

[30] |

|

41 HCC; 10 controls |

Surgery |

TERT, TP53 and CTNNB1 |

Targeted-sequencing |

Detection of ctDNA predicted shorter recurrence-free survival |

[31] |

|

10 HCC |

Surgery TACE RFA |

Methylation of GSTP1 and RASSF1A or TP53 mutation |

Methylation-specific PCR and sanger sequencing |

Detecting ctDNA in urine was feasible and predicted recurrence |

[32] |

|

218 HCC; 81 cirrhotic |

NA |

TERT promoter mutation (C228T and C250T) |

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and sanger sequencing |

TERT promoter mutation can be used as an early biomarker of HCC and is associated with survival |

[33] |

|

34 HCC |

Surgery |

ctDNA (harboring SNV or CNV) |

Targeted-sequencing and low coverage whole-genome sequencing |

ctDNA can detect minimal residual disease (MRD) and predict survival |

[28] |

|

95 HCC; 45 cirrhotic |

Surgery |

TERT promoter mutation (C228T) |

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) |

Detection of mutated TERT promoter was associated with lower survival |

[34] |

|

59 HCC |

Surgery TACE RFA Systemic chemotherapy BSC |

Single nucleotide variant (SNV) in a panel of 69 genes |

Targeted-sequencing |

Mutated MLH1 in plasma was associated with lower survival |

[35] |

|

130 HCC |

TACE Systemic chemotherapy |

TERT promoter mutation |

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) |

Detection of mutated TERT promoter was associated with lower survival |

[36] |

|

895 HCC |

Surgery/NA |

TP53 mutation (R249S) |

Droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) |

Detection of mutated TP53 was associated with lower survival |

[37] |

|

22 HCC |

TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitors) |

Genes of the PI3K/MTOR pathway |

Targeted-sequencing and ddPCR |

Mutations of genes in the PI3K/MTOR pathway are associated with lower survival in patients treated with TKI |

[38] |

|

Methylation Changes |

|||||

|

72 HCC; 37 benign liver diseases; 41 healthy controls |

- |

APC, GSTP1, RASSF1A, and SFRP1 |

Methylation-specific PCR |

Methylation of RASSF1A was associated with poor survival |

[39] |

|

1098 HCC; 835 controls |

NA |

8-marker panel |

Targeted bisulfite sequencing |

Methylation-based classifier predicted survival |

[40] |

|

10 HCC |

TACE RFA Surgery |

Methylation of GSTP1 and RASSF1A or TP53 mutation |

Methylation-specific PCR and sanger sequencing |

Detecting ctDNA in urine was feasible and predicted recurrence |

[32] |

|

203 HCC; 104 chronic viral hepatitis B or C; 50 healthy controls |

NA |

APC, COX2, RASSF1A (+miR-203) |

Methylation-specific PCR |

Classifier predicted survival |

[41] |

|

172 HCC |

NA |

LINE-1 |

Methylation-specific PCR |

Hypomethylation of LINE-1 was associated with lower survival |

[42] |

|

155 HCC; 60 chronic HBV; 20 healthy controls |

Surgery |

IGFBP7 |

Methylation-specific PCR |

Methylation of IGFBP7 was associated with lower survival |

[43] |

|

43 HCC (+347 HCC from TCGA Atlas); 5 cirrhotic; 6 benign liver lesions |

- |

CTCFL |

Methylation-specific PCR |

Hypomethylation of CTCFL was associated with higher recurrence and lower survival |

[44] |

3. Circulating Free RNAs (cfRNAs)

RNAs include a large family of members: micro, long non-coding, messenger or exosomal RNAs. Herein, we will focus on the most commonly investigated circulating RNAs in liquid biopsies (Table 2).

Table 2. Circulating free RNAs (cfRNAs) and exosomes.

|

Number of Patients |

Treatment |

Biomarkers |

Technique |

Main Finding |

[Ref.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

miRNA |

|||||

|

195 HCC 54 cirrhotic |

Surgery Transplant TACE RFA sorafenib |

miR-1 and miR-12 |

qRT-PCR |

Low level of miR-1 was associated with lower survival |

[50] |

|

122 HCC |

Surgery |

miR-122 |

qRT-PCR |

Low level of miR-122 was associated with lower survival |

[51] |

|

120 HCC |

Surgery RFA |

MiR-21, miR-26a, and miR-29a |

qRT-PCR |

Low levels of miR-26a and miR-29a were associated with lower survival |

[52] |

|

30 HCC; 30 controls |

Surgery |

miR-155, miR-96 and miR-99a |

qRT-PCR |

High levels of miR-155 and miR-96 were associated with lower survival |

[53] |

|

116 HCC |

NA |

Circulating miR |

Whole miRNome profling |

Low levels of miR-424-5p, miR-101-3p or high levels of miR-128, miR-139-5p, miR-382-5p and miR410 were associated with lower survival |

[54] |

|

41 HCC; 20 controls |

Surgery transplant |

miR193a-5p |

qRT-PCR |

High level of miR193a-5p was associated with lower survival |

[55] |

|

70 HBV-related HCC 70 HBV 50 healthy controls |

Surgery |

miRNA-223-3p |

qRT-PCR |

Low level of miRNA-223-3p was associated with lower survival |

[56] |

|

mRNA |

|||||

|

50 HCC; 50 controls |

Surgery |

VEGF-165 |

qRT-PCR |

Detection of circulating VEGF mRNA (isoform 165) was associated with higher recurrence and recurrence-related mortality |

[57] |

|

38 HCC |

Surgery |

AFP |

qRT-PCR |

Detection of AFP mRNA was associated with extrahepatic recurrence and shorter disease-free survival |

[58] |

|

343 HCC |

Surgery TACE RFA Systemic chemotherapy Radiotherapy BSC |

AFP and hTERT |

qRT-PCR |

Detection of AFP mRNA or hTERT mRNA was not associated with survival |

[59] |

|

Exosomes |

|||||

|

59 HCC |

Transplant |

miR-718 |

qRT-PCR |

Recurrence was associated with higher level of exosomal miR-718 |

[60] |

|

30 HCC |

Surgery |

miR-665 |

qRT-PCR |

High level of exosomal miR-665 was associated with lower survival |

[61] |

|

79 HCC |

Surgery Transplant TACE RFA Sorafenib BSC |

miR-21 and lncRNA-ATB |

qRT-PCR |

High levels of exosomal miR-21 and lncRNA-ATB were associated with lower survival |

[62] |

|

126 HCC; 21 healthy controls |

Surgery |

miR-638 |

qRT-PCR |

Low level of exosomal miR-638 was associated with lower survival |

[63] |

|

31 HCC; 3 CLD; 11 healthy controls |

NA |

RN7SL1 S fragment |

qRT-PCR |

High expression of RN7SL1 S fragment was associated with lower survival |

[64] |

|

124 HCC; 100 healthy controls |

Surgery |

AKT3 |

qRT-PCR |

High level of exosomal circulating AKT3 was associated with higher recurrence and lower survival rates |

[65] |

|

104 HCC; 55 CLD; 50 healthy controls |

Surgery |

miR-320a |

qRT-PCR |

Low serum exosomal miR-320a was associated with lower survival |

[66] |

4. Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): Exosomes

Exosomes are a type of EV, nanoparticles encapsulating a variety of cargo including DNA and RNA fragments in a lipidic double-layer, which protects them from enzymatic degradation. With these unique features, circulating exosomes allow RNAs to circulate without being degraded plasma. Their nature and roles remain largely unknown but exosomes may not only be passively released from apoptotic cells into the bloodstream. Data suggested they may be actively secreted, acting as messengers in the cell-to-cell communication network, conferring them priceless values like accuracy and tissue-specificity [68,69,70,71].

In HCC, the data exploring the contribution of exosomes remain limited, particularly for prognosis. However, these analytes have demonstrated promising and polyvalent performance in other cancer types both for diagnosis and prognosis [72,73].

Several projects analyzed exosomal miRNAs. In a cohort of 59 HCC patients, authors found a correlation between tumor recurrence after liver transplantation and a higher level of miR-718 [60]. Similar signals were detected after liver resection and other exosomal miRNAs: high levels of miR-665 or low levels of miR-638 and miR-320a were identified as predictors of poor survival [61,63,66]. In a cohort of 79 HCC patients of different stages receiving various treatments, Lee et al. focused on two candidates: a miRNA (miR-21) and a long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) (lncRNA-ATB). On multivariable analysis, both markers were independently associated with disease progression [62]. A recent study profiled 57 plasma cell-free RNA transcriptomes and 20 exosomal RNA transcriptomes to test their diagnostic and prognostic performance. RN7SL1 and its S fragment were promising, showing a high diagnostic accuracy (AUC = 0.87). Furthermore, a higher concentration of RN7SL1 S fragment was an independent factor of worse survival [64]. The analyses of blood samples from 124 HCC patients treated with surgical resection and 100 healthy controls identified an exosomal circular RNA (circAKT3) as a prognostic factor; a high level of circAKT3 predicted both higher recurrence and lower survival [65].

5. Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

CTCs play a pivotal role during the hematogenous dissemination of cancers. Most technologies to analyze CTCs include two steps: enrichment (isolation) and detection (identification). The development of sensitive and specific technologies is challenging. Estimated to be released by cancers of intermediate and advanced stages, CTCs are probably more useful for prognostication than for early cancer detection. In this context, studies have demonstrated the prognostic value of CTC enumeration in different cancers including HCC [74,75]. More sophisticated technologies, like single-cell RNA sequencing, have allowed further characterization of CTC subtypes [76]. Studies exploring the value of CTCs for HCC prognostication are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs).

|

Number of Patients |

Treatment |

Technique of Detection |

Main Finding |

[Ref.] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

44 HCC 30 HCV 39 cirrhosis 38 healthy controls |

Surgery NA |

Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells (ISET) |

Presence and number of detected CTCs were associated with shorter survival |

[77] |

|

85 HCC 37 benign liver diseases 20 healthy volunteers 14 miscellaneous advanced cancers other than HCC |

Surgery NA |

Antibody-coated magnetic beads |

Presence and number of detected CTCs correlated with tumor size, portal vein tumor thrombus, differentiation status, TNM stage and Milan criteria |

[78] |

|

82 HCC |

Surgery |

Multicolor flow cytometry |

Circulating cancer stem cells (CSC) are associated with higher rates of intra- and extra-hepatic recurrence, decreased recurrence-free survival (RFS) and overall survival (OS) rates |

[79] |

|

96 HCC 31 healthy controls 21 viral hepatitis 8 cirrhosis |

Surgery |

Magnetic cell sorting (Lin28B) |

Detection of CTCs expressing Lin28B was associated with early recurrence |

[80] |

|

60 HCC |

Surgery NA |

Flow cytometry (ICAM-1) |

Detection of CTCs expressing ICAM-1 was associated with shorter disease-free survival |

[81] |

|

123 HCC |

Surgery |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Detection of CTCs (EpCAM+) was associated with higher recurrence |

[75] |

|

59 HCC 19 controls |

NA |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Detection of CTCs was associated with lower overall survival |

[82] |

|

122 HCC 120 controls |

Surgery TACE Radiotherapy |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Peri-treatment decrease of detected CTC reflected treatment response |

[83] |

|

109 HCC |

Surgery TACE RFA sorafenib |

Flow cytometry (ASGPR and CPS1) |

pERK+/pAkt-CTCs correlated with progression-free survival and predicted response to systemic therapy (sorafenib) |

[84] |

|

72 HCC |

Surgery |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic nanoparticals (MagVigen, Nvigen) |

Detection of CTCs expressing AFP was associated with metastatic disease |

[85] |

|

69 HCC 31 controls |

Surgery Transplant TACE RFA Sorafenib BSC |

Imaging flow cytometry (EpCAM, AFP, glypican-3 and DNA-PK together with analysis of size, morphology and DNA content) (ImageStream) |

Detection of CTCs was associated with lower survival |

[86] |

|

57 HCC |

Surgery |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

CTCs detection was associated with higher recurrence and lower recurrence-free survival after liver resection |

[87] |

|

14 HCC 16 CCA 4 GBC |

Surgery |

SE-iFISH |

Detection of small CTCs with CNV (chromosome 8) was associated with lower survival |

[88] |

|

199 HCC |

Surgery |

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) |

Anterior approach was associated with a decreased dissemination of CTCs compared to conventional approach, resulting in poorer outcomes. |

[89] |

|

73 HCC |

Surgery |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Analyzes of blood samples collected in different vessels revealed a spatial heterogeneity of CTCs distribution whose biology was associated with recurrence pattern. |

[90] |

|

130 HCC |

Surgery TACE |

qRT-PCR test platform |

CTCs detection was associated with recurrence after liver resection |

[91] |

|

112 HCC |

Surgery |

CanPatrolTM system (filtration by size) and Tri-color RNA-ISH assay |

The presence of CTCs and the proportion of mesenchymal-CTC (M-CTCs) were associated with recurrence |

[92] |

|

61 HCC 19 non-HCC |

TACE TARE RFA Systemic therapy |

Antibody-based platform |

Vimentin (VIM)-positive CTCs predicted OS and faster recurrence after curative-intent surgical or locoregional therapy in potentially curable early-stage HCC |

[93] |

|

139 HCC 23 controls |

Surgery |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Surgical resection induces a release of CTCs |

[94] |

|

105 HCC |

Surgery |

ISET |

ΔCTCs is an independent predictor of lower survival and higher recurrence in patients |

[95] |

|

85 HCC 27 non-HCC |

Surgery |

Flow cytometry (GPC3) |

GPC3 positive-CTCs detection was associated with lower survival |

[96] |

|

50 HCC |

Transplant |

Negative enrichment and immunofluorescence in situ hybridization (imFISH) |

CTCs detection was associated with early recurrence after liver transplant |

[97] |

|

137 HCC |

Surgery |

ISET |

CTCs detection was associated with early recurrence after liver resection |

[98] |

|

87 HCC 7 cirrhosis 8 healthy controls |

Transplant Surgery TACE TARE RFA Systemic therapy |

Antibody-based platform |

Detection of CTCs expressing PD-L1 were associated with shorter OS and predicted response to immunotherapy |

[99] |

|

128 HCC |

Surgery ± TACE |

EpCAM antibody-coated magnetic beads (CellSearch) |

Adjuvant TACE provided survival and recurrence benefits in patients with positive preoperative CTCs |

[100] |

|

193 HCC |

Transplant |

Antibody-based platform (ChimeraX®-i120) |

CTCs detection was associated with recurrence after liver transplant |

[101] |

Most studies investigating CTCs included HCC patients undergoing surgical resection. In 2004, Vona G et al. isolated and enumerated CTCs based on their size and morphology, showing that the presence and number of detected CTCs were associated with shorter survival [77]. CellSearch® is an isolation system that targets EpCAM positive cells. It was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and became the most commonly used technique for CTC enumeration. Its use remains debated in HCC as only around 30% of HCC cells express EpCAM [102]. Nonetheless, several studies utilized this approach in HCC, demonstrating that the detection of EpCAM positive CTCs was associated with higher tumor recurrence [75] or lower survival [82,87]. Thereafter, more sophisticated technologies for CTC isolation have been reported, like ImageStream flow cytometry. A study has provided the proof-of-concept of this technology, demonstrating its capacity to detect CTCs using a panel of markers. This technology also generates high-resolution images of isolated CTCs [103]. Its value in detecting CTCs was confirmed and the CTC count was further confirmed as an independent prognostic factor [86]. Other reports have aimed at exploring the impact of subgroups of CTCs, clustered based on cell surface markers, RNA expression or genomic aberrations. Studies using surface markers to detect CTCs with cancer stem cell-like [79,80,81] or mesenchymal [92] features, revealed their clinical value to predict tumor recurrence. CTCs expressing AFP were also associated with an increased risk of metastasis [85], whereas CTCs harboring CNV (chr 8) predicted worse survival [88]. Ha et al. used a simple isolation technique but introduced the concept of ΔCTC, referring to the perioperative fluctuation of detected CTCs, which appeared as an independent factor of lower survival and higher recurrence rates after partial hepatectomy [95]. Besides their intrinsic biological traits, CTC dissemination seemed to be impacted by treatment. Data suggested that surgery-induced manipulation of the liver is associated with a release of CTCs [94]. A comparison between anterior and conventional surgical approaches suggested that the latter was associated with a higher release of CTCs as well as poorer outcomes [89]. Toso et al. described five steps during orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) in HCC patients to minimize CTC dissemination and thereby the risk of recurrence [104].

Recent studies also underscored the relevance of CTC analysis in patients undergoing OLT for HCC, highlighting an association between CTC detection and recurrence [97,101].

Guiding decision-making would be another application of CTCs. For example, selection of patients who would benefit from adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) after surgery or to predict response to systemic therapies like tyrosine kinase inhibitors or immunotherapy [84,99,100]. An interesting study analyzed CTCs using samples collected from different vessels. By doing so, they were able to demonstrate spatial heterogeneity in the distribution of CTCs, with a predominance of epithelial status at release, which gradually switched to EMT-activated phenotype during hematogenous transit [90]. Overall, data consistently identified that the number of CTCs was a surrogate of poor prognosis, predicting higher recurrence and/or lower survival. A recent meta-analysis and data from experimental models corroborated these findings [105,106].

2. Challenges and Future Perspectives

The field of liquid biopsy has numerous challenges. Besides those related to cost and technology, there is a limited understanding of the fundamental mechanisms responsible for the release of tumor molecular components to the bloodstream. A better understanding of these mechanisms would provide new tools and targets to improve the diagnostic and prognostic performance of liquid biopsy analytes. Gasparello et al. performed one of the few studies of liquid biopsies in animal models, identifying potential gateways regulating the detection of ctDNA [107]. Experimental models will be instrumental to better understand these mechanisms. ITH has emerged as a major drawback for singlebiopsy biomarker development. The clinical impact of ITH is progressively recognized, even at early tumor stages [108]. Liquid biopsy can help address the clinical issues posed by ITH as it likely includes a molecular composite of tumor components released by any potential tumor area. Thus, it is not restricted by the specific tumor section sampled by a needle-biopsy. There are few data of integrative analysis of different analytes within the liquid biopsy space (e.g., simultaneous evaluation of ctDNA and CTCs). Finally, it is key to have prospective data to determine the exact role of liquid biopsy as a prognostic biomarker in HCC, and which is the clinical niche that will be better suited for this transformative technology.

3. Conclusions

While data on liquid biopsy in HCC remain scanter than for other malignancies, there has been numerous recent publications demonstrating its prognostic value in HCC patients. Potential contributions in HCC prognostication were detected for each of the tumor byproducts (e.g., DNA, RNA, exosomes and cells). The next step will be to determine the optimal way of integrating liquid biopsy in the clinical management of HCC patients and to modify current clinical practice guidelines accordingly.

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: I.L., A.V., O.D., N.D., E.M.; Acquisition of data:

I.L.; Analysis and interpretation of data: I.L., A.V., E.M.; Drafting of the manuscript: I.L.; Critical

revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: I.L., A.V., O.D., N.D., E.M. All authors

have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank Jill Gregory for the design of the figures.

Conflicts of Interest: AV has received consulting fees from Guidepoint, Fujifilm, Boehringer Ingelheim, FirstWord, and MHLife Sciences; advisory board fees from Exact Sciences, Nucleix, Gilead and

NGM Pharmaceuticals; and research support from Eisai.

References

1. Villanueva, A. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1450–1462. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

2. World Health Organization. Projections of Mortality and Causes of Death, 2016 to 2060. Available online: http://www.who.int/

healthinfo/global_burden_disease/projections/en/ (accessed on 14 October 2018).

3. Llovet, J.M.; Bru, C.; Bruix, J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: The BCLC staging classification. Semin. Liver. Dis. 1999, 19,

329–338. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

4. Bruix, J.; Sherman, M.; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: An

update. Hepatology 2011, 53, 1020–1022. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

5. He, C.; Peng, W.; Liu, X.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Wen, T.F. Post-treatment alpha-fetoprotein response predicts prognosis of patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e16557. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

6. Labgaa, I.; Torrecilla, S.; Martinez-Quetglas, I.; Sia, D. Genetics of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Risk Stratification, Clinical Outcome,

and Implications for Therapy. Digest. Disease Interv. 2017, 01, 055–065. [CrossRef]

7. Goossens, N.; Labgaa, I.; Villanueva, A. Nontumor Prognostic Factors in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. In Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

Current Clinical Oncology; Carr, B.I., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [CrossRef]

8. Hoshida, Y.; Villanueva, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Peix, J.; Chiang, D.Y.; Camargo, A.; Gupta, S.; Moore, J.; Wrobel, M.J.; Lerner, J.; et al.

Gene expression in fixed tissues and outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1995–2004. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

9. Villanueva, A.; Hoshida, Y.; Battiston, C.; Tovar, V.; Sia, D.; Alsinet, C.; Cornella, H.; Liberzon, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Kumada, H.;

et al. Combining clinical, pathology, and gene expression data to predict recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology

2011, 140, 1501–1512. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

10. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma.

J. Hepatol. 2018, 69, 182–236. [CrossRef]

11. Heimbach, J.K.; Kulik, L.M.; Finn, R.S.; Sirlin, C.B.; Abecassis, M.M.; Roberts, L.R.; Zhu, A.X.; Murad, M.H.; Marrero, J.A. AASLD

guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018, 67, 358–380. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

12. Silva, M.A.; Hegab, B.; Hyde, C.; Guo, B.; Buckels, J.A.; Mirza, D.F. Needle track seeding following biopsy of liver lesions in the

diagnosis of hepatocellular cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut 2008, 57, 1592–1596. [CrossRef]

13. Labgaa, I.; Villanueva, A. Liquid biopsy in liver cancer. Discov. Med. 2015, 19, 263–273.

14. von Felden, J.; Garcia-Lezana, T.; Schulze, K.; Losic, B.; Villanueva, A. Liquid biopsy in the clinical management of hepatocellular

carcinoma. Gut 2020, 69, 2025–2034. [CrossRef]

Cancers 2021, 13, 659 13 of 17

15. Labgaa, I.; Craig, A.J.; Villanueva, A. Diagnostic and Prognostic Performance of Liquid Biopsy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

In Liquid Biopsy in Cancer Patients. Current Clinical Pathology; Giordano, A., Rolfo, C., Russo, A., Eds.; Humana Press: Cham,

Switzerland, 2017. [CrossRef]

16. Cohen, J.D.; Li, L.; Wang, Y.; Thoburn, C.; Afsari, B.; Danilova, L.; Douville, C.; Javed, A.A.; Wong, F.; Mattox, A.; et al. Detection

and localization of surgically resectable cancers with a multi-analyte blood test. Science 2018, 359, 926–930. [CrossRef]

17. Bettegowda, C.; Sausen, M.; Leary, R.J.; Kinde, I.; Wang, Y.; Agrawal, N.; Bartlett, B.R.; Wang, H.; Luber, B.; Alani, R.M.; et al.

Detection of circulating tumor DNA in early- and late-stage human malignancies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2014, 6, 224. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

18. Tie, J.; Wang, Y.; Tomasetti, C.; Li, L.; Springer, S.; Kinde, I.; Silliman, N.; Tacey, M.; Wong, H.L.; Christie, M.; et al. Circulating

tumor DNA analysis detects minimal residual disease and predicts recurrence in patients with stage II colon cancer. Sci. Transl.

Med. 2016, 8, 346. [CrossRef]

19. Tie, J.; Cohen, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Christie, M.; Simons, K.; Lee, M.; Wong, R.; Kosmider, S.; Ananda, S.; McKendrick, J.; et al.

Circulating Tumor DNA Analyses as Markers of Recurrence Risk and Benefit of Adjuvant Therapy for Stage III Colon Cancer.

JAMA Oncol. 2019. [CrossRef]

20. Lee, B.; Lipton, L.; Cohen, J.; Tie, J.; Javed, A.A.; Li, L.; Goldstein, D.; Burge, M.; Cooray, P.; Nagrial, A.; et al. Circulating tumor

DNA as a potential marker of adjuvant chemotherapy benefit following surgery for localized pancreatic cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2019,

30, 1472–1478. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

21. Parikh, A.R.; Leshchiner, I.; Elagina, L.; Goyal, L.; Levovitz, C.; Siravegna, G.; Livitz, D.; Rhrissorrakrai, K.; Martin, E.E.; Van

Seventer, E.E.; et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting acquired resistance and tumor heterogeneity in gastrointestinal

cancers. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 1415–1421. [CrossRef]

22. Russo, M.; Misale, S.; Wei, G.; Siravegna, G.; Crisafulli, G.; Lazzari, L.; Corti, G.; Rospo, G.; Novara, L.; Mussolin, B.; et al.

Acquired Resistance to the TRK Inhibitor Entrectinib in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 36–44. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

23. Russo, M.; Siravegna, G.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Corti, G.; Crisafulli, G.; Ahronian, L.G.; Mussolin, B.; Kwak, E.L.; Buscarino, M.;

Lazzari, L.; et al. Tumor Heterogeneity and Lesion-Specific Response to Targeted Therapy in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Discov.

2016, 6, 147–153. [CrossRef]

24. Siravegna, G.; Mussolin, B.; Buscarino, M.; Corti, G.; Cassingena, A.; Crisafulli, G.; Ponzetti, A.; Cremolini, C.; Amatu, A.;

Lauricella, C.; et al. Clonal evolution and resistance to EGFR blockade in the blood of colorectal cancer patients. Nat. Med. 2015,

21, 795–801. [CrossRef]

25. De Rubis, G.; Rajeev Krishnan, S.; Bebawy, M. Liquid Biopsies in Cancer Diagnosis, Monitoring, and Prognosis. Trends Pharmacol.

Sci. 2019, 40, 172–186. [CrossRef]

26. Jiang, P.; Chan, C.W.; Chan, K.C.; Cheng, S.H.; Wong, J.; Wong, V.W.; Wong, G.L.; Chan, S.L.; Mok, T.S.; Chan, H.L.; et al.

Lengthening and shortening of plasma DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112,

E1317–E1325. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

27. Labgaa, I.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; D’Avola, D.; Craig, A.J.; von Felden, J.; Martins-Filho, S.N.; Sia, D.; Stueck, A.; Ward, S.C.;

Fiel, M.I.; et al. A pilot study of ultra-deep targeted sequencing of plasma DNA identifies driver mutations in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Oncogene 2018, 37, 3740–3752. [CrossRef]

28. Cai, Z.; Chen, G.; Zeng, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, Z.; Huang, Y.; Xin, F.; Qiu, L.; Xu, H.; Zhang, W.; et al. Comprehensive Liquid Profiling of

Circulating Tumor DNA and Protein Biomarkers in Long-Term Follow-Up Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer

Res. 2019, 25, 5284–5294. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

29. Oh, C.R.; Kong, S.Y.; Im, H.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, M.K.; Yoon, K.A.; Cho, E.H.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, J.; Kang, J.; et al. Genome-wide copy

number alteration and VEGFA amplification of circulating cell-free DNA as a biomarker in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma

patients treated with Sorafenib. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 292. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

30. Ono, A.; Fujimoto, A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Akamatsu, S.; Hiraga, N.; Imamura, M.; Kawaoka, T.; Tsuge, M.; Abe, H.; Hayes, C.N.; et al.

Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis for Liver Cancers and Its Usefulness as a Liquid Biopsy. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 1,

516–534. [CrossRef]

31. Liao, W.; Yang, H.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Ge, P.; Ren, J.; Xu, W.; Lu, X.; Sang, X.; Zhong, S.; et al. Noninvasive detection of tumorassociated mutations from circulating cell-free DNA in hepatocellular carcinoma patients by targeted deep sequencing. Oncotarget

2016, 7, 40481–40490. [CrossRef]

32. Hann, H.W.; Jain, S.; Park, G.; Steffen, J.D.; Song, W.; Su, Y.H. Detection of urine DNA markers for monitoring recurrent

hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatoma Res. 2017, 3, 105–111. [CrossRef]

33. Jiao, J.; Watt, G.P.; Stevenson, H.L.; Calderone, T.L.; Fisher-Hoch, S.P.; Ye, Y.; Wu, X.; Vierling, J.M.; Beretta, L. Telomerase reverse

transcriptase mutations in plasma DNA in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma or cirrhosis: Prevalence and risk factors.

Hepatol. Commun. 2018, 2, 718–731. [CrossRef]

34. Oversoe, S.K.; Clement, M.S.; Pedersen, M.H.; Weber, B.; Aagaard, N.K.; Villadsen, G.E.; Gronbaek, H.; Hamilton-Dutoit,

S.J.; Sorensen, B.S.; Kelsen, J. TERT promoter mutated circulating tumor DNA as a biomarker for prognosis in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 1433–1440. [CrossRef]

35. Kim, S.S.; Eun, J.W.; Choi, J.H.; Woo, H.G.; Cho, H.J.; Ahn, H.R.; Suh, C.W.; Baek, G.O.; Cho, S.W.; Cheong, J.Y. MLH1 singlenucleotide variant in circulating tumor DNA predicts overall survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2020,

10, 17862. [CrossRef]

Cancers 2021, 13, 659 14 of 17

36. Hirai, M.; Kinugasa, H.; Nouso, K.; Yamamoto, S.; Terasawa, H.; Onishi, Y.; Oyama, A.; Adachi, T.; Wada, N.; Sakata, M.; et al.

Prediction of the prognosis of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma by TERT promoter mutations in circulating tumor DNA.

J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

37. Shen, T.; Li, S.F.; Wang, J.L.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, S.; Chen, H.T.; Xiao, Q.Y.; Ren, W.H.; Liu, C.; Peng, B.; et al. TP53 R249S

mutation detected in circulating tumour DNA is associated with Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with or without

hepatectomy. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 2834–2847. [CrossRef]

38. von Felden, J.; Craig, A.J.; Garcia-Lezana, T.; Labgaa, I.; Haber, P.K.; D’Avola, D.; Asgharpour, A.; Dieterich, D.; Bonaccorso,

A.; Torres-Martin, M.; et al. Mutations in circulating tumor DNA predict primary resistance to systemic therapies in advanced

hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene 2020. [CrossRef]

39. Huang, Z.H.; Hu, Y.; Hua, D.; Wu, Y.Y.; Song, M.X.; Cheng, Z.H. Quantitative analysis of multiple methylated genes in plasma for

the diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2011, 91, 702–707. [CrossRef]

40. Xu, R.H.; Wei, W.; Krawczyk, M.; Wang, W.; Luo, H.; Flagg, K.; Yi, S.; Shi, W.; Quan, Q.; Li, K.; et al. Circulating tumour DNA

methylation markers for diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Mater. 2017, 16, 1155–1161. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

41. Lu, C.Y.; Chen, S.Y.; Peng, H.L.; Kan, P.Y.; Chang, W.C.; Yen, C.J. Cell-free methylation markers with diagnostic and prognostic

potential in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 6406–6418. [CrossRef]

42. Yeh, C.C.; Goyal, A.; Shen, J.; Wu, H.C.; Strauss, J.A.; Wang, Q.; Gurvich, I.; Safyan, R.A.; Manji, G.A.; Gamble, M.V.; et al. Global

Level of Plasma DNA Methylation is Associated with Overall Survival in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Ann. Surg.

Oncol. 2017, 24, 3788–3795. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

43. Li, F.; Qiao, C.Y.; Gao, S.; Fan, Y.C.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, K. Circulating cell-free DNA of methylated insulin-like growth factorbinding protein 7 predicts a poor prognosis in hepatitis B virus-associated hepatocellular carcinoma after hepatectomy. Free Radic.

Res. 2018, 52, 455–464. [CrossRef]

44. Chen, M.M.; Zhao, R.C.; Chen, K.F.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Z.J.; Wei, Y.G.; Jian, Y.; Sun, A.M.; Qin, L.; Li, B.; et al. Hypomethylation

of CTCFL promoters as a noninvasive biomarker in plasma from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasma 2020, 67,

909–915. [CrossRef]

45. Chiang, D.Y.; Villanueva, A.; Hoshida, Y.; Peix, J.; Newell, P.; Minguez, B.; LeBlanc, A.C.; Donovan, D.J.; Thung, S.N.; Sole, M.;

et al. Focal gains of VEGFA and molecular classification of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 6779–6788. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

46. Schulze, K.; Imbeaud, S.; Letouze, E.; Alexandrov, L.B.; Calderaro, J.; Rebouissou, S.; Couchy, G.; Meiller, C.; Shinde, J.;

Soysouvanh, F.; et al. Exome sequencing of hepatocellular carcinomas identifies new mutational signatures and potential

therapeutic targets. Nat. Genet. 2015, 47, 505–511. [CrossRef]

47. Totoki, Y.; Tatsuno, K.; Covington, K.R.; Ueda, H.; Creighton, C.J.; Kato, M.; Tsuji, S.; Donehower, L.A.; Slagle, B.L.; Nakamura, H.;

et al. Trans-ancestry mutational landscape of hepatocellular carcinoma genomes. Nat. Genet. 2014, 46, 1267–1273. [CrossRef]

48. Hernandez-Meza, G.; von Felden, J.; Gonzalez-Kozlova, E.E.; Garcia-Lezana, T.; Peix, J.; Portela, A.; Craig, A.J.; Sayols, S.;

Schwartz, M.; Losic, B.; et al. DNA methylation profiling of human hepatocarcinogenesis. Hepatology 2020. [CrossRef]

49. Villanueva, A.; Portela, A.; Sayols, S.; Battiston, C.; Hoshida, Y.; Mendez-Gonzalez, J.; Imbeaud, S.; Letouze, E.; Hernandez-Gea, V.;

Cornella, H.; et al. DNA methylation-based prognosis and epidrivers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2015, 61, 1945–1956.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

50. Koberle, V.; Kronenberger, B.; Pleli, T.; Trojan, J.; Imelmann, E.; Peveling-Oberhag, J.; Welker, M.W.; Elhendawy, M.; Zeuzem, S.;

Piiper, A.; et al. Serum microRNA-1 and microRNA-122 are prognostic markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur. J.

Cancer 2013, 49, 3442–3449. [CrossRef]

51. Xu, Y.; Bu, X.; Dai, C.; Shang, C. High serum microRNA-122 level is independently associated with higher overall survival rate in

hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Tumour. Biol. 2015, 36, 4773–4776. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

52. Cho, H.J.; Kim, S.S.; Nam, J.S.; Kim, J.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, B.; Wang, H.J.; Kim, B.W.; Lee, J.D.; Kang, D.Y.; et al. Low levels of

circulating microRNA-26a/29a as poor prognostic markers in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent curative

treatment. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2017, 41, 181–189. [CrossRef]

53. Ning, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, B.; Wei, W.; Yang, A.; Li, J.; Zhang, L. miR-155, miR-96 and miR-99a as potential diagnostic and prognostic

tools for the clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 18, 3381–3387. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

54. Jin, Y.; Wong, Y.S.; Goh, B.K.P.; Chan, C.Y.; Cheow, P.C.; Chow, P.K.H.; Lim, T.K.H.; Goh, G.B.B.; Krishnamoorthy, T.L.; Kumar, R.;

et al. Circulating microRNAs as Potential Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9,

10464. [CrossRef]

55. Loosen, S.H.; Wirtz, T.H.; Roy, S.; Vucur, M.; Castoldi, M.; Schneider, A.T.; Koppe, C.; Ulmer, T.F.; Roeth, A.A.; Bednarsch, J.; et al.

Circulating levels of microRNA193a-5p predict outcome in early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239386.

[CrossRef]

56. Pratedrat, P.; Chuaypen, N.; Nimsamer, P.; Payungporn, S.; Pinjaroen, N.; Sirichindakul, B.; Tangkijvanich, P. Diagnostic and

prognostic roles of circulating miRNA-223-3p in hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232211.

[CrossRef]

Cancers 2021, 13, 659 15 of 17

57. Jeng, K.S.; Sheen, I.S.; Wang, Y.C.; Gu, S.L.; Chu, C.M.; Shih, S.C.; Wang, P.C.; Chang, W.H.; Wang, H.Y. Prognostic significance of

preoperative circulating vascular endothelial growth factor messenger RNA expression in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma:

A prospective study. World J. Gastroenterol. 2004, 10, 643–648. [CrossRef]

58. Morimoto, O.; Nagano, H.; Miyamoto, A.; Fujiwara, Y.; Kondo, M.; Yamamoto, T.; Ota, H.; Nakamura, M.; Wada, H.; Damdinsuren,

B.; et al. Association between recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and alpha-fetoprotein messenger RNA levels in peripheral

blood. Surg. Today 2005, 35, 1033–1041. [CrossRef]

59. Kong, S.Y.; Park, J.W.; Kim, J.O.; Lee, N.O.; Lee, J.A.; Park, K.W.; Hong, E.K.; Kim, C.M. Alpha-fetoprotein and human telomerase

reverse transcriptase mRNA levels in peripheral blood of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2009,

135, 1091–1098. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

60. Sugimachi, K.; Matsumura, T.; Hirata, H.; Uchi, R.; Ueda, M.; Ueo, H.; Shinden, Y.; Iguchi, T.; Eguchi, H.; Shirabe, K.; et al.

Identification of a bona fide microRNA biomarker in serum exosomes that predicts hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after

liver transplantation. Br. J. Cancer 2015, 112, 532–538. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

61. Qu, Z.; Wu, J.; Wu, J.; Ji, A.; Qiang, G.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Ding, Y. Exosomal miR-665 as a novel minimally invasive biomarker for

hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis and prognosis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 80666–80678. [CrossRef]

62. Lee, Y.R.; Kim, G.; Tak, W.Y.; Jang, S.Y.; Kweon, Y.O.; Park, J.G.; Lee, H.W.; Han, Y.S.; Chun, J.M.; Park, S.Y.; et al. Circulating

exosomal noncoding RNAs as prognostic biomarkers in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 2019, 144, 1444–1452.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

63. Shi, M.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, L.; Yan, S.; Wang, Y.G.; Lu, X.J. Decreased levels of serum exosomal miR-638 predict poor prognosis in

hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Cell Biochem. 2018, 119, 4711–4716. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

64. Tan, C.; Cao, J.; Chen, L.; Xi, X.; Wang, S.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, L.; Wang, D.; Yin, J.; et al. Noncoding RNAs Serve as Diagnosis

and Prognosis Biomarkers for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Chem. 2019, 65, 905–915. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

65. Luo, Y.; Liu, F.; Gui, R. High expression of circulating exosomal circAKT3 is associated with higher recurrence in HCC patients

undergoing surgical treatment. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 33, 276–281. [CrossRef]

66. Hao, X.; Xin, R.; Dong, W. Decreased serum exosomal miR-320a expression is an unfavorable prognostic factor in patients with

hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519896144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

67. Lin, X.J.; Chong, Y.; Guo, Z.W.; Xie, C.; Yang, X.J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, S.P.; Xiong, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Min, J.; et al. A serum microRNA

classifier for early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma: A multicentre, retrospective, longitudinal biomarker identification

study with a nested case-control study. Lancet Oncol. 2015, 16, 804–815. [CrossRef]

68. Maisano, D.; Mimmi, S.; Russo, R.; Fioravanti, A.; Fiume, G.; Vecchio, E.; Nistico, N.; Quinto, I.; Iaccino, E. Uncovering the

Exosomes Diversity: A Window of Opportunity for Tumor Progression Monitoring. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 180. [CrossRef]

69. Hoshino, A.; Costa-Silva, B.; Shen, T.L.; Rodrigues, G.; Hashimoto, A.; Tesic Mark, M.; Molina, H.; Kohsaka, S.; Di Giannatale, A.;

Ceder, S.; et al. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature 2015, 527, 329–335. [CrossRef]

70. Hoshino, A.; Kim, H.S.; Bojmar, L.; Gyan, K.E.; Cioffi, M.; Hernandez, J.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Rodrigues, G.; Molina, H.; Heissel, S.;

et al. Extracellular Vesicle and Particle Biomarkers Define Multiple Human Cancers. Cell 2020, 182, 1044–1061.e1018. [CrossRef]

71. Costa-Silva, B.; Aiello, N.M.; Ocean, A.J.; Singh, S.; Zhang, H.; Thakur, B.K.; Becker, A.; Hoshino, A.; Mark, M.T.; Molina, H.;

et al. Pancreatic cancer exosomes initiate pre-metastatic niche formation in the liver. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 816–826. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

72. Iaccino, E.; Mimmi, S.; Dattilo, V.; Marino, F.; Candeloro, P.; Di Loria, A.; Marimpietri, D.; Pisano, A.; Albano, F.; Vecchio, E.;

et al. Monitoring multiple myeloma by idiotype-specific peptide binders of tumor-derived exosomes. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 159.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

73. Nistico, N.; Maisano, D.; Iaccino, E.; Vecchio, E.; Fiume, G.; Rotundo, S.; Quinto, I.; Mimmi, S. Role of Chronic Lymphocytic

Leukemia (CLL)-Derived Exosomes in Tumor Progression and Survival. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 244. [CrossRef]

74. Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen,

L.W.; et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351,

781–791. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

75. Sun, Y.F.; Xu, Y.; Yang, X.R.; Guo, W.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, S.J.; Shi, R.Y.; Hu, B.; Zhou, J.; Fan, J. Circulating stem cell-like epithelial cell

adhesion molecule-positive tumor cells indicate poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. Hepatology

2013, 57, 1458–1468. [CrossRef]

76. D’Avola, D.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Martins-Filho, S.N.; Craig, A.; Labgaa, I.; von Felden, J.; Kimaada, A.; Bonaccorso, A.; Tabrizian,

P.; Hartmann, B.M.; et al. High-density single cell mRNA sequencing to characterize circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular

carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11570. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

77. Vona, G.; Estepa, L.; Beroud, C.; Damotte, D.; Capron, F.; Nalpas, B.; Mineur, A.; Franco, D.; Lacour, B.; Pol, S.; et al. Impact of

cytomorphological detection of circulating tumor cells in patients with liver cancer. Hepatology 2004, 39, 792–797. [CrossRef]

78. Xu, W.; Cao, L.; Chen, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.F.; Qian, H.H.; Kang, X.Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, J.; Shi, L.H.; et al. Isolation of circulating

tumor cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma using a novel cell separation strategy. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 3783–3793.

[CrossRef] [PubMed]

79. Fan, S.T.; Yang, Z.F.; Ho, D.W.; Ng, M.N.; Yu, W.C.; Wong, J. Prediction of posthepatectomy recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma

by circulating cancer stem cells: A prospective study. Ann. Surg. 2011, 254, 569–576. [CrossRef]

Cancers 2021, 13, 659 16 of 17

80. Cheng, S.W.; Tsai, H.W.; Lin, Y.J.; Cheng, P.N.; Chang, Y.C.; Yen, C.J.; Huang, H.P.; Chuang, Y.P.; Chang, T.T.; Lee, C.T.; et al.

Lin28B is an oncofetal circulating cancer stem cell-like marker associated with recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE

2013, 8, e80053. [CrossRef]

81. Liu, S.; Li, N.; Yu, X.; Xiao, X.; Cheng, K.; Hu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, S.; Liu, S. Expression of intercellular adhesion

molecule 1 by hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells and circulating tumor cells. Gastroenterology 2013, 144, 1031–1041.e1010.

[CrossRef]

82. Schulze, K.; Gasch, C.; Staufer, K.; Nashan, B.; Lohse, A.W.; Pantel, K.; Riethdorf, S.; Wege, H. Presence of EpCAM-positive

circulating tumor cells as biomarker for systemic disease strongly correlates to survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 2165–2171. [CrossRef]

83. Guo, W.; Yang, X.R.; Sun, Y.F.; Shen, M.N.; Ma, X.L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, B.; et al. Clinical significance

of EpCAM mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma by an optimized negative enrichment and

qRT-PCR-based platform. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 4794–4805. [CrossRef]

84. Li, J.; Shi, L.; Zhang, X.; Sun, B.; Yang, Y.; Ge, N.; Liu, H.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Qian, H.; et al. pERK/pAkt phenotyping in

circulating tumor cells as a biomarker for sorafenib efficacy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 2016,

7, 2646–2659. [CrossRef]

85. Jin, J.; Niu, X.; Zou, L.; Li, L.; Li, S.; Han, J.; Zhang, P.; Song, J.; Xiao, F. AFP mRNA level in enriched circulating tumor cells

from hepatocellular carcinoma patient blood samples is a pivotal predictive marker for metastasis. Cancer Lett. 2016, 378, 33–37.

[CrossRef]

86. Ogle, L.F.; Orr, J.G.; Willoughby, C.E.; Hutton, C.; McPherson, S.; Plummer, R.; Boddy, A.V.; Curtin, N.J.; Jamieson, D.; Reeves,

H.L. Imagestream detection and characterisation of circulating tumour cells—A liquid biopsy for hepatocellular carcinoma?

J. Hepatol. 2016, 65, 305–313. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

87. von Felden, J.; Schulze, K.; Krech, T.; Ewald, F.; Nashan, B.; Pantel, K.; Lohse, A.W.; Riethdorf, S.; Wege, H. Circulating tumor

cells as liquid biomarker for high HCC recurrence risk after curative liver resection. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 89978–89987. [CrossRef]

[PubMed]

88. Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, A.; Wang, X.; Tang, R.; Zhang, X.; Yin, H.; Liu, M.; Wang, D.D.; et al. Quantified postsurgical small

cell size CTCs and EpCAM(+) circulating tumor stem cells with cytogenetic abnormalities in hepatocellular carcinoma patients

determine cancer relapse. Cancer Lett. 2018, 412, 99–107. [CrossRef]

89. Hao, S.; Chen, S.; Tu, C.; Huang, T. Anterior Approach to Improve the Prognosis in HCC Patients Via Decreasing Dissemination

of EpCAM(+) Circulating Tumor Cells. J. Gastrointest Surg. 2017, 21, 1112–1120. [CrossRef]

90. Sun, Y.F.; Guo, W.; Xu, Y.; Shi, Y.H.; Gong, Z.J.; Ji, Y.; Du, M.; Zhang, X.; Hu, B.; Huang, A.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells

from Different Vascular Sites Exhibit Spatial Heterogeneity in Epithelial and Mesenchymal Composition and Distinct Clinical

Significance in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 547–559. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

91. Guo, W.; Sun, Y.F.; Shen, M.N.; Ma, X.L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, C.Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xu, Y.; Hu, B.; Zhang, M.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells

with Stem-Like Phenotypes for Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapeutic Response Evaluation in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin.

Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 2203–2213. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

92. Qi, L.N.; Xiang, B.D.; Wu, F.X.; Ye, J.Z.; Zhong, J.H.; Wang, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; Chen, Z.S.; Ma, L.; Chen, J.; et al. Circulating Tumor

Cells Undergoing EMT Provide a Metric for Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res.

2018, 78, 4731–4744. [CrossRef]

93. Court, C.M.; Hou, S.; Winograd, P.; Segel, N.H.; Li, Q.W.; Zhu, Y.; Sadeghi, S.; Finn, R.S.; Ganapathy, E.; Song, M.; et al. A novel

multimarker assay for the phenotypic profiling of circulating tumor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2018, 24,

946–960. [CrossRef]

94. Yu, J.J.; Xiao, W.; Dong, S.L.; Liang, H.F.; Zhang, Z.W.; Zhang, B.X.; Huang, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Zhang, W.G.; Luo, H.P.; et al. Effect of

surgical liver resection on circulating tumor cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2018, 18, 835. [CrossRef]

95. Ha, Y.; Kim, T.H.; Shim, J.E.; Yoon, S.; Jun, M.J.; Cho, Y.H.; Lee, H.C. Circulating tumor cells are associated with poor outcomes in

early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: A prospective study. Hepatol. Int. 2019, 13, 726–735. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

96. Hamaoka, M.; Kobayashi, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Mashima, H.; Ohdan, H. Clinical significance of glypican-3-positive circulating tumor

cells of hepatocellular carcinoma patients: A prospective study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0217586. [CrossRef]

97. Chen, Z.; Lin, X.; Chen, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, L.; Wang, D.; Ma, Y.; Ju, W.; Chen, M.; et al. Analysis of preoperative

circulating tumor cells for recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020,

8, 1067. [CrossRef]

98. Zhou, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, H.; Leng, C.; Hou, B.; Zhou, C.; Hu, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Preoperative circulating tumor cells to

predict microvascular invasion and dynamical detection indicate the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2020, 20,

1047. [CrossRef]

99. Winograd, P.; Hou, S.; Court, C.M.; Lee, Y.T.; Chen, P.J.; Zhu, Y.; Sadeghi, S.; Finn, R.S.; Teng, P.C.; Wang, J.J.; et al. Hepatocellular

Carcinoma-Circulating Tumor Cells Expressing PD-L1 Are Prognostic and Potentially Associated With Response to Checkpoint

Inhibitors. Hepatol. Commun. 2020, 4, 1527–1540. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

100. Wang, P.X.; Sun, Y.F.; Zhou, K.Q.; Cheng, J.W.; Hu, B.; Guo, W.; Yin, Y.; Huang, J.F.; Zhou, J.; Fan, J.; et al. Circulating tumor cells

are an indicator for the administration of adjuvant transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-center,

retrospective, propensity-matched study. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e137. [CrossRef]

Cancers 2021, 13, 659 17 of 17

101. Wang, P.X.; Xu, Y.; Sun, Y.F.; Cheng, J.W.; Zhou, K.Q.; Wu, S.Y.; Hu, B.; Zhang, Z.F.; Guo, W.; Cao, Y.; et al. Detection of circulating

tumour cells enables early recurrence prediction in hepatocellular carcinoma patients undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Int.

2020. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

102. Yamashita, T.; Forgues, M.; Wang, W.; Kim, J.W.; Ye, Q.; Jia, H.; Budhu, A.; Zanetti, K.A.; Chen, Y.; Qin, L.X.; et al. EpCAM and

alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 1451–1461.

[CrossRef]

103. Dent, B.M.; Ogle, L.F.; O’Donnell, R.L.; Hayes, N.; Malik, U.; Curtin, N.J.; Boddy, A.V.; Plummer, E.R.; Edmondson, R.J.;

Reeves, H.L.; et al. High-resolution imaging for the detection and characterisation of circulating tumour cells from patients with

oesophageal, hepatocellular, thyroid and ovarian cancers. Int. J. Cancer 2016, 138, 206–216. [CrossRef]

104. Toso, C.; Mentha, G.; Majno, P. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Five steps to prevent recurrence. Am. J.

Transplant. 2011, 11, 2031–2035. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

105. Cui, K.; Ou, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, S.; Sun, Z. Clinical value of circulating tumor cells for the diagnosis and prognosis of hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020, 99, e22242. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

106. Yan, J.; Fan, Z.; Wu, X.; Xu, M.; Jiang, J.; Tan, C.; Wu, W.; Wei, X.; Zhou, J. Circulating tumor cells are correlated with disease

progression and treatment response in an orthotopic hepatocellular carcinoma model. Cytometry A 2015, 87, 1020–1028. [CrossRef]

107. Gasparello, J.; Allegretti, M.; Tremante, E.; Fabbri, E.; Amoreo, C.A.; Romania, P.; Melucci, E.; Messana, K.; Borgatti, M.; Giacomini,

P.; et al. Liquid biopsy in mice bearing colorectal carcinoma xenografts: Gateways regulating the levels of circulating tumor DNA

(ctDNA) and miRNA (ctmiRNA). J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 124. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

108. Losic, B.; Craig, A.J.; Villacorta-Martin, C.; Martins-Filho, S.N.; Akers, N.; Chen, X.; Ahsen, M.E.; von Felden, J.; Labgaa, I.;

D’Avola, D.; et al. Intratumoral heterogeneity and clonal evolution in liver cancer. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 291. [CrossRef]

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers13040659