Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) is an organic pollutant with persistence and carcinogenicity. They are universally present in the environment and food processing. Biological approaches toward remediating PAHs-contaminated sites are a viable, economical, and environmentally friendly alternative compared to conventional physical and/or chemical remediation methods. Recently, various strategies relating to low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs) have been developed to enhance the microbial degradation of PAHs. However, the remaining challenge is to reveal the role of LMWOAs in the PAHs biodegradation process, and the latter limits researchers from expanding the application scope of biodegradation.

- low molecular weight organic acids

- polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- bioremediation

1. Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), persistent organic pollutants, are widely distributed in the environment and food processing [1]. Over the past decades, increasing amounts of PAHs have been generated from the incomplete combustion of organic substances, such as coal, oil, wood, and tobacco [2][3]. The strong genotoxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties of PAHs pose a severe threat to human health and, therefore, raise global concerns [4][5][6]. In total, 16 widespread PAHs compounds were listed as priority pollutants by the US EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) [7][8]. The majority of PAHs are chemically stable with low solubility in water and worse adsorption towards solid particles [9]. Hence, universal and transferable approaches to degrading the PAHs are still demanded.

Conventional methods, including physical or chemical remediation approaches, have already been developed to overcome the PAHs pollution challenge. However, physical or chemical remediation approaches are often costly and may cause secondary environmental pollution [10][11][12]. Bioremediation provides a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable alternative [13][14]. Generally, soil organic matters, such as humins, low molecular weight organic acids, amino acids, are favorable for the biodegradation of pollutants [15][16][17]. For instance, electrochemically-reduced humins were able to enhance microbial denitrification. Solid-phase humins improve all reducing reactions from nitrate to nitrogen gas [18][19]. In addition, the degrading rate of petroleum hydrocarbons was significantly affected by soil organic content [20].

Among various dissolved soil organic matters, low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs, MW < 500 Da) also facilitate the degradation of pollutants by plants or microbes. LMWOAs can be discovered in the root exudates and the microbial decomposition of plant litter [21][22][23][24]. LMWOAs include mono-, di-, and tricarboxylic acids containing hydroxyl groups as well as unsaturated carbon and often exist as the dissociated anions (carboxylates) [25][26]. The release of LMWOAs from root exudates could be influenced through different factors, such as the acidity of the soil, the absence/presence of insoluble minerals, type of soil microorganisms, and plant developmental stage [17][27]. These produced soluble elements which are easily available for microbial growth [26][28][29]. The synthesis and/or secretion of LMWOAs by microbes play essential roles in the process of biotic or abiotic stress responses [30]. Furthermore, the root exudate organic acids are crucial for the rhizoremediation of heavy metals and PAHs. To date, although some excellent reviews thoroughly elucidate the importance of the root exudate in heavy metals and PAHs bioremediation ][26][31][32][33], few focused on investigating the role that individual compounds (such as carboxylates, amino acids) of root exudate in PAHs bioremediation [26].

Recently, the addition of LMWOAs has been an attractive and promising strategy to enhance the capacity of microbes to degrade organic pollutants, especially PAHs (Table 1). LMWOAs showed a powerful ability to chelate multivalent cations (e.g., Fe3+, Al3+) and thus significantly influenced the mobility, solubility, and fate of pollutants in nature [34]. In addition, glutaric acid and citric acid improve the growth rates and the vital enzymatic activities of microorganisms in the degradation process, resulting in increased organic pollutants biodegradation [25][35]. PAHs degradation research undoubtedly benefits from the occurrence of various LMWOAs towards microorganisms. Meanwhile, an in-depth understanding of how LMWOAs affect microbial bioremediation at the molecular level is in demand to view the comprehensive biodegradation landscape and inspire us to develop additional bio stimulation techniques for engineering the efficiency of bioremediation systems.

Table 1. The predominant low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs) applied to enhance microbial degradation of pollutants.

| LMWOAs | Microorganism | Pollutants | Main Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citric, succinic, and aconitic acid | - | PAHs contaminated soil | Enhance PAHs degradation | [36] |

| Citric and malic acid | - | Phenanthrene | Enhance desorption | [37] |

| Oxalic acid | Microbial community | Agricultural field contaminated with PAHs | Promote PAHs dissipation, enhanced the microbial biomass and activity | [38] |

| Citric, lactic, malic, oxalic, and succinic acids mixture | Stenotrophomonas sp., Microbacterium sp., and Arthrobacter sp. | Benzo(a)pyrene and pyrene | Enhance biodegradation | [39] |

| Eight organic acids mixed: oxalic, formic, tartaric, lactic, acetic, malic, maleic, and citric acid | Microbial populations | Phenanthrene and pyrene | Influence the bioavailability of PAHs and microbial activity | [40] |

| Root exudates were prepared by mixing glucose, oxalic acid, malic acid, and serine | Soil microbial community | Pyrene | Enhance biodegradation | [41] |

| Glutaric acid | Pseudomonas aeruginosa NY3 | Hexadecanol | Increase strain growth rates, hexadecane monooxygenase activities, and enhance biodegradation | [35] |

| Citric and malonate acid | Microbial community | Petroleum hydrocarbons | Stimulate heterotrophic microbial activity | [25] |

| Citric acid, oxalic acid, malic acid | - | Phenanthrene and pyrene | Enhance bioavailability | [42] |

| Oxalic and malic acids | - | Phenanthrene | Favor photodegradation on Fe(III)–clay | [43] |

| Citric acid, oxalic acid, and malic acid | - | Naphthalene, acenaphthene, fluorene, phenanthrene, fluoranthrene, pyrene, benzo(a) anthrancene, and benzo fluoranthrene | Promote bound PAH residues release, and enhance the PAH availability in soils | [44] |

| Citric and malic acids | - | Phenanthrene and pyrene | Promote the release and enhanced the availability of PAHs in soil | [45] |

| Malic acid | - | Phenanthrene | Enhance desorption | [46] |

| Acetic acid, oxalic acid, tartaric acid, and citric acid | - | Phenanthrene | Enhance desorption | [47] |

| Citric and oxalic acid | - | Phenanthrene and pyrene | Enhance desorption | [48] |

| Citric, oxalic, and malic acid | - | Phenanthrene | Enhance desorption | [49] |

| Citric and oxalic acid | - | Phenanthrene and pyrene | Increase phenanthrene and pyrene availability | [50] |

| Succinic, tartaric, malic, malonic, oxalic, citric, or ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid | p,p′-DDE | Enhance desorption | [34] |

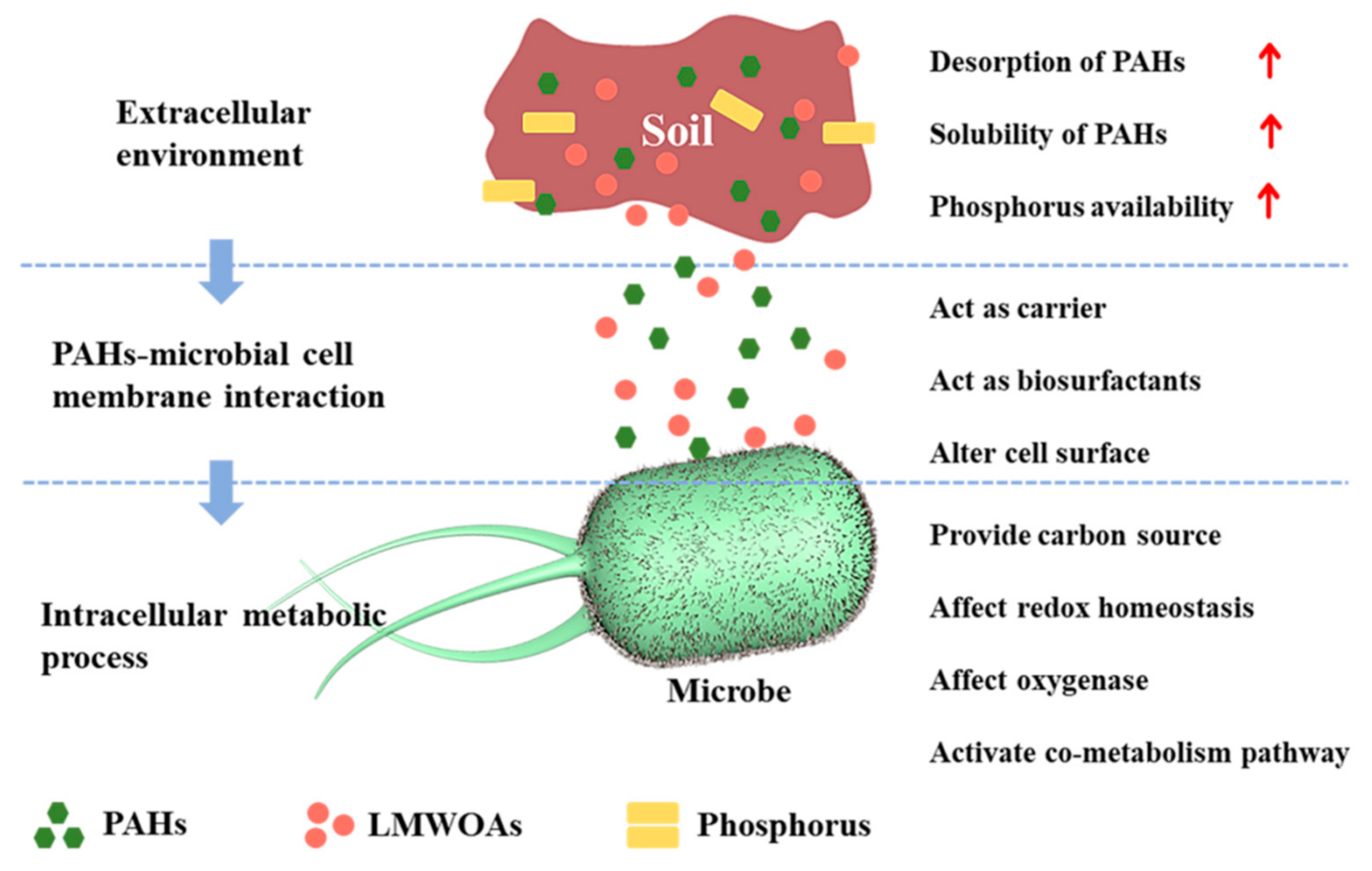

The influence of low molecular weight organic acids (LMWOAs) on the microbial degradation process of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) were shown in Figure 1).

2. The Application of LMWOAs in PAHs-Contamination Remediation

2.1. In Situ Remediation

In situ remediation is an approach to break down and purify contaminants by activating microorganisms present in the soil. Few studies have been reported about applying the LMWOAs toward in situ remediation of PAH. Through investigating the influence of LMWOAs on the in situ distribution of PAHs adsorption, Li et al. found that LMWOAs lead to the homogeneity of the PAHs in the mangrove sediment but also contribute to the enhancement of the particulate organic matter content [51]. Zhao et al. discovered that combining the nonionic surfactant (e.g., Tween80) with LMWOAs (e.g., citric acid) has improved performance compared to single surfactant in terms of in situ cleaning the PAHs contaminated soils [52]. Moreover, many LMWOAs, including citric acid, oxalic acid, and malic acid, are favorable for directly releasing the PAH-bound residues from soils [44].

2.2. Soil Flushing/Washing

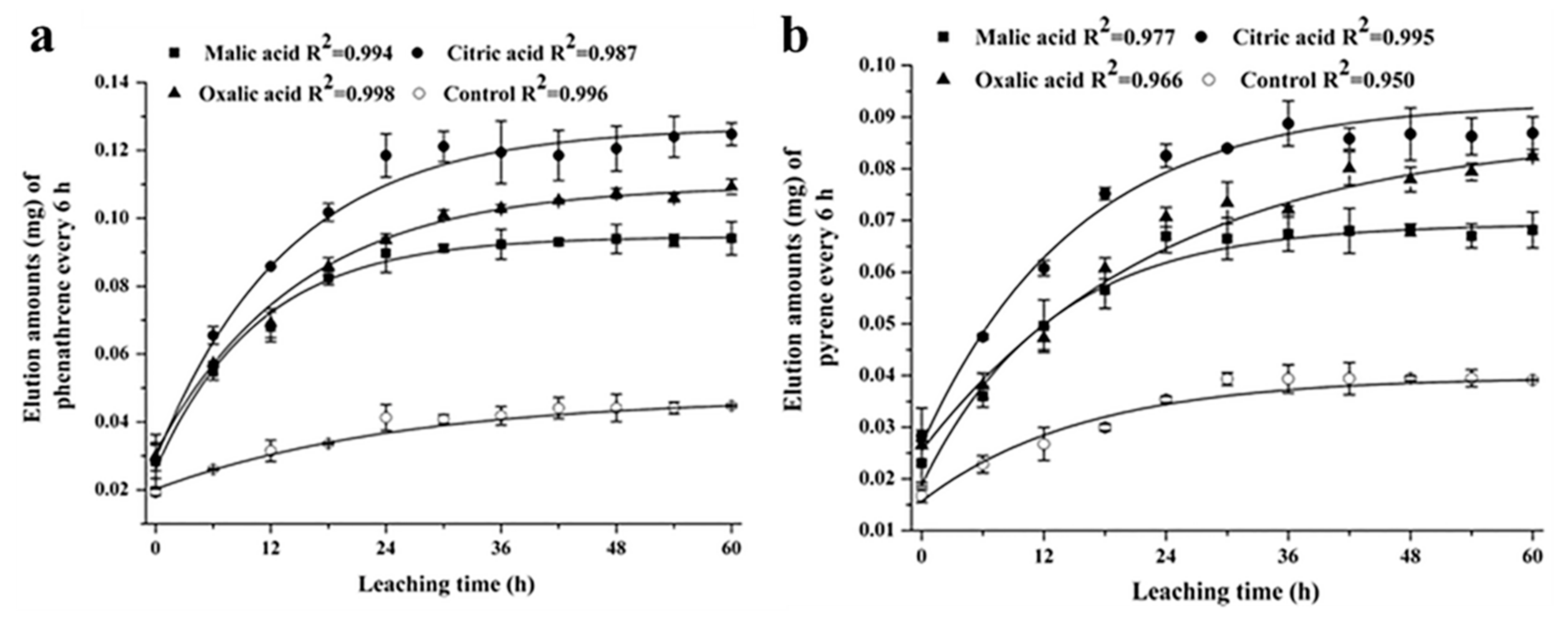

Soil flushing/washing, as an in situ chemical method of soil remediation, involves the extraction of PAHs via a fluid that was injected into the contaminated soil. LMWOAs as additives have been employed to remediate PAHs polluted soils through integrating into the soil flushing/washing technology [42][47][53]. For instance, Jia et al. observed that LMWOAs markedly promoted the release of phenanthrene and pyrene from sediment columns and, therefore, led to bioavailability enhancement (Figure 2). In detail, citric acid showed the best elution strength. With the increase in the concentration of citric acid from 0 to 160 mmol/L, the phenanthrene and pyrene in leachates enhanced from 0.045 and 0.039 mg to 0.125 and 0.087 mg, respectively [42]. Moreover, LMWOAs (e.g., acetic acid, oxalic acid, tartaric acid, and citric acid) promoted phenanthrene desorption in the soil–water system. Falciglia et al. applied citric acid as enhancers to break up calcium carbonate on the surface and thus accelerate the washing step to remove PAHs from seabed sediments [53]. These studies stressed the importance of LMWOAs involved in soil washing technologies to deal with the PAH-contaminated sites [47].

2.3. Others

In addition, LMWOAs have markedly influenced PAHs photolysis. Jia et al. pointed out that oxalic and malic acids favor the phenanthrene photodegradation on the photocatalytic material Fe(III)–smectite [43]. Applying LMWOAs oxalic acid with maize straw biochar also amended the dissipation of PAHs in soil, accompanying enhanced PAH degradation related to genera and functional genes [38][54]. The latter suggested that combining biochar with LMWOAs might be a feasible strategy for promoting PAHs biodegradation.

3. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

In brief, the strategy to apply LMWOAs in PAHs bioremediation is a cost-effective and environmentally sustainable approach, which is supported by considerable evidence. To improve LMWOAs’ performance and make them more competitive for industrial applications, we believe that more exciting results will be obtained if more efforts are made in the following directions:

(1) More detailed and direct evidence about how humic acids influence the apparent solubility and PAHs-microorganisms interactions are still required to investigate whether all LMWOAs have a similar function with humic acids.

(2) At present, since few research pieces have examined the mechanism of LMWOAs playing in PAHs’ intracellular metabolism within the anaerobic process, it is necessary to explore such direction to improve the application of LMWOAs in the actual PAHs pollution treatment process with a better understanding.

(3) Proteomics and metabolomics technologies are potential tools for elucidating PAHs degradation process mechanisms with microbes at the molecular level [55]. High throughput “omics” technologies would help researchers reveal the complicated effect of LMWOAs in detail, from gene expression to whole-cell metabolic pathways.

(4) Advanced genetic tools, especially CRISPR/Cas9, can be employed to modify and optimize the target microbes’ PAH degradation capacity. Better microbial remediation strategies are required to be developed by integrating genetically edited microbial cells with optimal LMWOAs.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/w13040446

References

- Gao, Y.Z.; Ling, W.T. Comparison for plant uptake of phenanthrene and pyrene from soil and water. Biol. Fert. Soils 2006, 42, 387–394.

- Gao, Y.Z.; Zhu, L.Z. Plant uptake, accumulation and translocation of phenanthrene and pyrene in soils. Chemosphere 2004, 55, 1169–1178.

- Kim, T.J.; Lee, E.Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Cho, K.-S.; Ryu, H.W. Degradation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons by Burkholderia cepacia 2A-12. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 19, 411–417.

- Haritash, A.; Kaushik, C. Biodegradation aspects of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs): A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 1–15.

- Sayara, T.; Borras, E.; Caminal, G.; Sarra, M.; Sanchez, A. Bioremediation of PAHs-contaminated soil through composting: Influence of bioaugmentation and biostimulation on contaminant biodegradation. Int. Biodeter. Biodegr. 2011, 65, 859–865.

- Hu, J.; Aitken, M.D. Desorption of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons from field-contaminated soil to a two-dimensional hydrophobic surface before and after bioremediation. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 542–547.

- Lamichhane, S.; Krishna, K.B.; Sarukkalige, R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) removal by sorption: A review. Chemosphere 2016, 148, 336–353.

- Zhang, Z.Z.; Hou, Z.W.; Yang, C.Y.; Ma, C.Q.; Tao, F.; Xu, P. Degradation of n-alkanes and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in petroleum by a newly isolated Pseudomonas aeruginosa DQ8. Bioresource Technol. 2011, 102, 4111–4116.

- Peng, R.H.; Xiong, A.S.; Xue, Y.; Fu, X.Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, W.; Tian, Y.S.; Yao, Q.H. Microbial biodegradation of poly-aromatic hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2008, 32, 927–955.

- Li, H.; Qu, R.; Li, C.; Guo, W.; Han, X.; He, F.; Ma, Y.; Xing, B. Selective removal of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) from soil washing effluents using biochars produced at different pyrolytic temperatures. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 163, 193–198.

- Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Chen, B. Adsorption of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons by Graphene and Graphene Oxide Nanosheets. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 4817–4825.

- Antosova, B.; Hrabak, P.; Antos, V.; Waclawek, S. Chemical oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbins in water by ferrates (VI). Ecol. Chem. Eng. S. Inz. Ekol. S 2020, 27, 529–542.

- Bisht, S.; Pandey, P.; Bhargava, B.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, V.; Sharma, K.D. Bioremediation of polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) using rhizosphere technology. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2015, 46, 7–21.

- Chaillan, F.; le Fleche, A.; Bury, E.; Phantavong, Y.H.; Grimont, P.; Saliot, A.; Oudot, J. Identification and biodegradation potential of tropical aerobic hydrocarbon-degrading microorganisms. Res. Microbiol. 2004, 155, 587–595.

- Gao, H.; Ma, J.; Xu, L.; Jia, L. Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin extractability and bioavailability of phenanthrene in humin and humic acid fractions from different soils and sediments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 8620–8630.

- Zhang, J.; He, M.; Lin, C.; Shi, Y. Phenanthrene sorption to humic acids, humin, and black carbon in sediments from typical water systems in China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2009, 166, 445–459.

- Adeleke, R.; Nwangburuka, C.; Oboirien, B. Origins, roles and fate of organic acids in soils: A review. South Afr. J. Bot. 2017, 108, 393–406.

- Xiao, Z.; Awata, T.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Katayama, A. Enhanced denitrification of Pseudomonas stutzeri by a bioelectrochemical system assisted with solid-phase humin. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2016, 122, 85–91.

- Xiao, Z.; Awata, T.; Zhang, D.; Katayama, A. Denitrification by Pseudomonas stutzeri coupled with CO2 reduction by Sporomusa ovata with hydrogen as an electron donor assisted by solid-phase humin. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2016, 122, 307–313.

- Chen, C.-H.; Liu, P.-W.G.; Whang, L.-M. Effects of natural organic matters on bioavailability of petroleum hydrocarbons in soil-water environments. Chemosphere 2019, 233, 843–851.

- Xiao, M.; Wu, F. A review of environmental characteristics and effects of low-molecular weight organic acids in the surface ecosystem. J. Environ. Sci. 2014, 26, 935–954.

- Carson, K.C.; Holliday, S.; Glenn, A.R.; Dilworth, M.J. Siderophore and organic-acid production in root nodule bacteria. Arch. Microbiol. 1992, 157, 264–271.

- Strobel, B.W. Influence of vegetation on low-molecular-weight carboxylic acids in soil solution—A review. Geoderma 2001, 99, 169–198.

- Tedetti, M.; Kawamura, K.; Charrière, B.; Chevalier, N.; Sempéré, R. Determination of low molecular weight dicar-boxylic and ketocarboxylic acids in seawater samples. Anal. Chem. 2006, 78, 6012–6018.

- Martin, B.C.; George, S.J.; Price, C.A.; Shahsavari, E.; Ball, A.S.; Tibbett, M.; Ryan, M.H. Citrate and malonate increase microbial activity and alter microbial community composition in uncontaminated and diesel-contaminated soil microcosms. Soil 2016, 2, 487–498.

- Martin, B.C.; George, S.J.; Price, C.A.; Ryan, M.H.; Tibbett, M. The role of root exuded low molecular weight organic anions in facilitating petroleum hydrocarbon degradation: Current knowledge and future directions. Sci. Total. Environ. 2014, 472, 642–653.

- Badri, D.V.; Vivanco, J.M. Regulation and function of root exudates. Plant Cell Environ. 2009, 32, 666–681.

- Balogh-Brunstad, Z.; Keller, C.K.; Dickinson, J.T.; Stevens, F.; Li, C.; Bormann, B.T. Biotite weathering and nutrient uptake by ectomycorrhizal fungus, Suillus tomentosus, in liquid-culture experiments. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 2601–2618.

- Morgan, J.A.W.; Bending, G.D.; White, P.J. Biological costs and benefits to plant–microbe interactions in the rhizosphere. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 1729–1739.

- Brimecombe, M.; Lelj, F.D.; Lynch, J. The effect of root exudates on rhizosphere microbial populations. Rhizosphere 2001, 46, 9780429116698.

- Ryan, P.R.; Delhaize, E.; Jones, D.L. Function and mechanism of organic anion exudation from plant roots. Annu. Rev. Plant Phys. 2001, 52, 527–560.

- Sokolova, T.A. Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids in Soils: Sources, Composition, Concentrations, and Functions: A Review. Eurasian Soil Sci. 2020, 53, 580–594.

- Dinh, Q.T.; Dongli, L.; Tran, T.A.T.; Wang, D.; Liang, D. Role of organic acids on the bioavailability of selenium in soil: A review. Chemosphere 2017, 184, 618–635.

- White, J.C.; Mattina, M.I.; Lee, W.-Y.; Eitzer, B.D.; Iannucci-Berger, W. Role of organic acids in enhancing the desorption and uptake of weathered p,p′-DDE by Cucurbita pepo. Environ. Pollut. 2003, 124, 71–80.

- Nie, H.; Nie, M.; Xiao, T.; Wang, Y.; Tian, X. Hexadecane degradation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa NY3 promoted by glutaric acid. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 1423–1428.

- Sivaram, A.K.; Logeshwaran, P.; Lockington, R.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. The impact of low molecular weight organic acids from plants with C3 and C4 photosystems on the rhizoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contaminated soil. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100957.

- Vázquez-Cuevas, G.M.; Lag-Brotons, A.J.; Ortega-Calvo, J.J.; Stevens, C.J.; Semple, K.T. The effect of organic acids on the behaviour and biodegradation of 14C-phenanthrene in contaminated soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2020, 143, 107722.

- Li, X.; Song, Y.; Wang, F.; Bian, Y.; Jiang, X. Combined effects of maize straw biochar and oxalic acid on the dissipation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and microbial community structures in soil: A mechanistic study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 364, 325–331.

- Sivaram, A.K.; Logeshwaran, P.; Lockington, R.; Naidu, R.; Megharaj, M. Low molecular weight organic acids enhance the high molecular weight polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons degradation by bacteria. Chemosphere 2019, 222, 132–140.

- Jiang, S.; Xie, F.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Yan, C. Response of low-molecular-weight organic acids inmangrove root exudates to exposure of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 12484–12493.

- Lu, H.; Sun, J.; Zhu, L. The role of artificial root exudate components in facilitating the degradation of pyrene in soil. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 7130.

- Jia, H.; Lu, H.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; Dai, M.; Yan, C. Effects of root exudates on the leachability, distribution, and bioavailability of phenanthrene and pyrene from mangrove sediments. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 5566–5576.

- Jia, H.Z.; Chen, H.X.; Nulaji, G.; Li, X.Y.; Wang, C.Y. Effect of low-molecular-weight organic acids on pho-to-degradation of phenanthrene catalyzed by Fe(III)-smectite under visible light. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 266–271.

- Gao, Y.; Yuan, X.; Lin, X.; Sun, B.; Zhao, Z. Low-molecular-weight organic acids enhance the release of bound PAH residues in soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2015, 145, 103–110.

- Kong, H.; Sun, R.; Gao, Y.; Sun, B. Elution of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Soil Columns Using Low-Molecular-Weight Organic Acids. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2013, 77, 72–82.

- Sun, B.; Gao, Y.; Liu, J.; Sun, Y. The Impact of Different Root Exudate Components on Phenanthrene Availability in Soil. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2012, 76, 2041–2050.

- An, C.; Huang, G.; Wei, J.; Yu, H. Effect of short-chain organic acids on the enhanced desorption of phenanthrene by rhamnolipid biosurfactant in soil-water environment. Water Res. 2011, 45, 5501–5510.

- Gao, Y.Z.; Ren, L.L.; Ling, W.T.; Gong, S.S.; Sun, B.Q.; Zhang, Y. Desorption of phenanthrene and pyrene in soils by root exudates. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101, 1159–1165.

- Gao, Y.Z.; Ren, L.L.; Ling, W.T.; Kang, F.X.; Zhu, X.Z.; Sun, B.Q. Effects of low-molecular-weight organic acids on sorption-desorption of phenanthrene in soils. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2010, 74, 51–59.

- Ling, W.; Ren, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, X.; Sun, B. Impact of low-molecular-weight organic acids on the availability of phenanthrene and pyrene in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2009, 41, 2187–2195.

- Li, R.L.; Zhu, Y.X.; Zhang, Y. In situ visualization and quantitative investigation of the distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the micro-zones of mangrove sediment. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 219, 245–252.

- Zhao, B.; Che, H.; Wang, H.; Xu, J. Column Flushing of Phenanthrene and Copper (II) Co-Contaminants from Sandy Soil Using Tween 80 and Citric Acid. Soil Sediment Contam. Int. J. 2016, 25, 50–63.

- Falciglia, P.P.; Catalfo, A.; Finocchiaro, G.; Vagliasindi, F.G.A.; Romano, S.; de Guidi, G. Chemically assisted 2.45 GHz microwave irradiation for the simultaneous removal of mercury and organics from contaminated marine sediments. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 655–666.

- Li, X.N.; Song, Y.; Yao, S.; Bian, Y.R.; Gu, C.G.; Yang, X.L.; Wang, F.; Jiang, X. Can biochar and oxalic acid alleviate the toxicity stress caused by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil microbial communities? Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 695, 133897.

- Seo, J.-S.; Keum, Y.-S.; Li, Q.X. Bacterial Degradation of Aromatic Compounds. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2009, 6, 278–309.