Oxidative stress has been associated with many pathologies, in both human and animal medicine. Damage to tissue components such as lipids is a defining feature of oxidative stress and can lead to the generation of many oxidized products, including isoprostanes (IsoP).

- isoprostane

- oxidative stress

- lipid peroxidation

1. Introduction

Oxidative stress, the imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants leading to tissue damage, has been associated with many diseases in both humans and animals [1]. Oxidants are chemically reactive molecules that are responsible for the tissue damage associated with oxidative stress and are composed of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS). Produced in moderate amounts as a byproduct of energy generation, oxidants are used in numerous cell signaling and immune pathways under physiologic conditions [2]. Antioxidants are designed to counter oxidants and maintain homeostasis, contributing to what is termed redox balance. However, a disruption in the balance that favors excessive oxidant accumulation leads to oxidative stress [2]. Examples of human diseases with an oxidative stress-related component in their pathophysiology include Alzheimer’s disease, type II diabetes, and heart failure [3,4,5]. In veterinary species, oxidative stress has been associated with similar disorders such as canine counterpart of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type, metabolic stress in dairy cattle, and congestive heart failure in dogs [6,7,8]. Despite the evidence supporting oxidative stress as an important contributor to numerous pathologies, no clinical signs of the process are displayed [9]. Furthermore, it can be challenging to distinguish between redox balance and unchecked oxidants, thereby making it necessary to use specific measurements to determine if oxidative stress is occurring. In fact, the need for reliable oxidative stress biomarkers and an understanding of any physiologic roles they may play in disease pathogenesis has become a priority in the research community.

Broadly, a biomarker can be described as “a defined characteristic that is measured as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or responses to an exposure or intervention” [10]. Several biomarkers of oxidative stress can be identified due to the tissue damage that occurs as a function of increased interactions between ROS and biological molecules. Common biomarkers generated from the reactions between ROS and nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids include 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine, protein carbonyls, and isoprostanes (IsoP), respectively [11,12]. However, the most favorable biomarkers must be more than merely measurable; they should also show specificity for a particular process, have prognostic value, or correlate with pathology [13].

Since their discovery in the early 1990s, IsoP have become one of the most widely used biomarkers of in vivo oxidative stress because they are highly sensitive and specific, can be measured noninvasively from numerous biological tissues and fluids, and are chemically stable [14,15]. In addition to IsoP themselves, IsoP metabolites are also valuable biomarkers. The metabolite 2,3-dinor-5, 6-dihydro-8-iso-prostaglandin F2α, for instance, is only generated in the liver from plasma IsoP and has a longer half-life than its parent compound. Therefore, its presence is considered an accurate representation of systemic oxidative stress over time [16]. Indeed, increased IsoP and IsoP metabolites have been associated with many human oxidative stress-related pathologies, including metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease [17]. However, while IsoP continuously become more popular in human medicine, studies regarding their potential role in disease pathogenesis remain sparse. Furthermore, literature of IsoP in veterinary species is relatively limited. This review will discuss the history, biosynthesis, and detection of IsoP, followed by current use and knowledge gaps regarding their role in veterinary medicine. Finally, the review will conclude with thoughts on future considerations for IsoP to be used successfully in veterinary medicine.

2. History

Isoprostanes are a relatively new oxidative stress biomarker, having only been characterized in vivo in the last 30 years. However, the earliest evidence of IsoP formation surfaced from in vitro work completed by Pryor and Stanley in the 1970s. They found that when methyl linolenate was autoxidized, a bicyclic endoperoxide was formed as a precursor to prostaglandin-like compounds [18]. In the 1980s, it was shown that the lower side chains of prostaglandin D2 (PGD2) will isomerize in aqueous solutions to form isomers of 9α,11β-PGF2α when reduced by 11-ketoreductase [19]. Later attempts to describe the presence of these compounds in vivo lead to the discovery of what are now termed isoprostanes [20]. In the early 1990s, Morrow and colleagues used mass spectrometry to characterize the 9α,11β-PGF2α isomers discovered by Wendelborn et al. [19]. They were prompted by the fact that the peaks generated by the 9α,11β-PGF2α isomers increased around 50-fold when the plasma was analyzed after several months of storage at −20 °C when compared to the plasma that was analyzed immediately after collection [21]. Furthermore, the authors found that the addition of antioxidants to the plasma samples would reduce the formation of F-ring prostaglandin-like compounds. This suggested that the molecules were generated independently of enzymatic pathways. First was the discovery of prostaglandin (PG) F2-like compounds, termed the F2-isoprostanes [21]. Shortly thereafter, Morrow et al. determined that PGE- and PGD-isoprostanes could be generated in vivo as well [22].

Although these earliest discovered IsoP were derived from arachidonic acid, it was soon determined that other polyunsaturated fatty acids could also generate IsoP in the face of interactions with free radicals. Later in the 90s, the omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) were found to produce F3-IsoP and F4-neuroprostanes, respectively [23,24,25]. Within a decade of the omega-3 IsoP discoveries, the omega-6 fatty acid, adrenic acid, was found to produce its own class of IsoP when undergoing interactions with free radicals [26]. Furthermore, IsoP are not exclusive to animals. Indeed, the plant-based omega-3 fatty acid α-linolenic acid will generate phytoprostanes (PhytoP) [27]. As the name suggests, IsoP are isomers of PG; however, they are synthesized by different mechanisms.

3. Use and Physiological Roles

3.1. Biomarkers of Lipid Peroxidation

3.2. Vascular Regulation

3.3. Inflammatory Effects

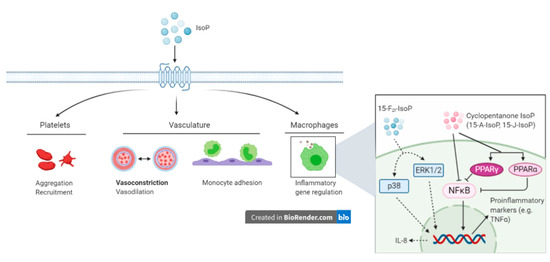

Outside the scope of vascular regulation, a limited number of studies have investigated other biological roles of IsoP. The intimate relationship between inflammation and oxidative stress suggests that IsoP may serve as an inflammatory mediator. Indeed, 15-F2t-IsoP is capable of inhibiting monocyte adhesion to human dermal microvascular endothelial cells, with maximal inhibition being noted at a concentration of 1 µM. However, in human umbilical vein endothelial cells, 15-F2t-IsoP enhanced monocyte adhesion at 10−10 to 10−8 M [101]. To characterize the mechanism by which 15-F2t-IsoP caused the suppression of monocyte adhesion to endothelial cells, the authors investigated several direct and indirect effects the IsoP may have. Of the proposed mechanisms, 15-F2t-IsoP inhibited monocyte adhesion induced by tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), had inhibitory effects comparable to those seen with a TP agonist, and appeared to be working through the p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK) pathway via a TP-mediated mechanism. Furthermore, 15-F2t-IsoP appears to encourage the production of a secondary inhibitor of monocyte adhesion, which acts in a TP-independent manner [101]. Scholz and coworkers discovered that 8-isoP also increase interleukin-8 expression in human macrophages [102]. Cyclopentenone IsoP (15-A2-IsoP and 15-J2-IsoP) are also capable of modulating macrophage inflammatory actions. The cyclopentenone IsoP abrogated inflammatory responses in both RAW 267.4 murine macrophages and primary macrophages via blocking translocation of nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) to the nucleus. Downstream effects of this blockade included inhibition of nitrite production, which was abrogated by performing glutathione adduction [103]. Interestingly, F2-IsoP does not inhibit nitrite production, which implicates the cyclopentenone moiety as being responsible for the anti-inflammatory responses. The cyclopentenone IsoP diverge in their actions under some circumstances though, highlighted by the potent activation of PPARγ by 15-J2-IsoP but not 15-A2-IsoP [103]. Additional evidence for the anti-inflammatory effects of IsoP has been offered for 15-A3t-IsoP, 14-A4t-NeuroP, and 4-F4t-NeuroP [104,105]. Given the impact IsoP have demonstrated in macrophages, it would likely be beneficial to investigate their effects on other cells that participate in the inflammatory response, such as other leukocytes and endothelial cells.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox10020145