The cardiovascular system can be programmed by a diversity of early-life insults, leading to cardiovascular disease (CVD) in adulthood. This notion is now termed developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD). Emerging evidence indicates hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a crucial regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis, plays a pathogenetic role in CVD of developmental origins. Conversely, early H2S-based interventions have proved beneficial in preventing adult-onset CVD in animal studies via reversing programming processes by so-called reprogramming.

- hydrogen sulfide

- cardiovascular disease

- hypertension

- atherosclerosis

- cysteine

- developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD)

- N-acetylcysteine

Note:All the information in this draft can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death worldwide, accounting for almost one third of all global deaths [1]. CVD is a cluster of disorders of the heart and blood vessels and is comprised of coronary heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease and other conditions. Although CVD is most common in older adults, atherosclerosis can begin in childhood and progress slowly across the life span [2]. Therefore, reducing the global burden of CVD by identifying children at risk and providing preventive interventions early are extremely important. Noteworthy, CVD can originate from the early stages of life, not only childhood but tracing back into the fetal life. This theory is now termed the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) by observing how a suboptimal environment in utero has an adverse influence on offspring outcomes in later life [3].

The fetal cardiovascular system is vulnerable to adverse early-life environmental insults [4]. Developmental plasticity accommodates morphological and functional changes during organogenesis, leading to endothelial dysfunction, stiffer vascular tree, small coronary arteries, low nephron endowment, and fewer cardiomyocytes, through a process known as cardiovascular programming [4–6]. So far, several mechanisms underlying cardiovascular programming have been proposed, like oxidative stress, nitric oxide (NO) deficiency, activation of the renin–angiotensin system (RAS), dysregulated nutrient-sensing signals, and dysbiosis of gut microbiota [4–6].

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), the third gasotransmitter, has emerged as a crucial regulator of cardiovascular homeostasis [7–9]. H2S exerts multifaceted biological functions, including vasodilatation, angiogenesis, antioxidant, anti-inflammation, mitochondria bioenergetics, and antiapoptosis [10,11]. In this regard, H2S-releasing drugs have been considered as potential therapeutics for CVD [7,8]. It is noteworthy that the DOHaD concept provides a strategy termed reprogramming to reverse or postpone the programming processes in early life, accordingly protecting offspring against many adult diseases of developmental origins [12]. Emerging evidence suggests that H2S can be used as a reprogramming strategy in hypertension of developmental origins [13]. Although H2S has been shown to have beneficial effects on CVD [7,8], whether it could serve as a reprogramming intervention for developmental origins of CVD remains largely unclear.

2. Hydrogen Sulfide in the Cardiovascular System

2.1. H2S Signaling Pathway

H2S, a colorless gas with a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs, was first identified as an environmental toxin in the 1700s and opened three centuries of research into its biological roles [14]. In the late 1990s, H2S was reclassified as the third gaseous signaling molecule, alongside nitric oxide (NO) and carbon monoxide (CO) [10]. Currently, H2S is known as a ubiquitous second messenger molecule with important functions in cardiovascular physiology [10,15]. Much of the previous work investigating the actions of H2S has been directly focused on incident CVD; however, there is a growing need to better understand the mechanisms and pathways of H2S signaling in CVD of developmental origins.

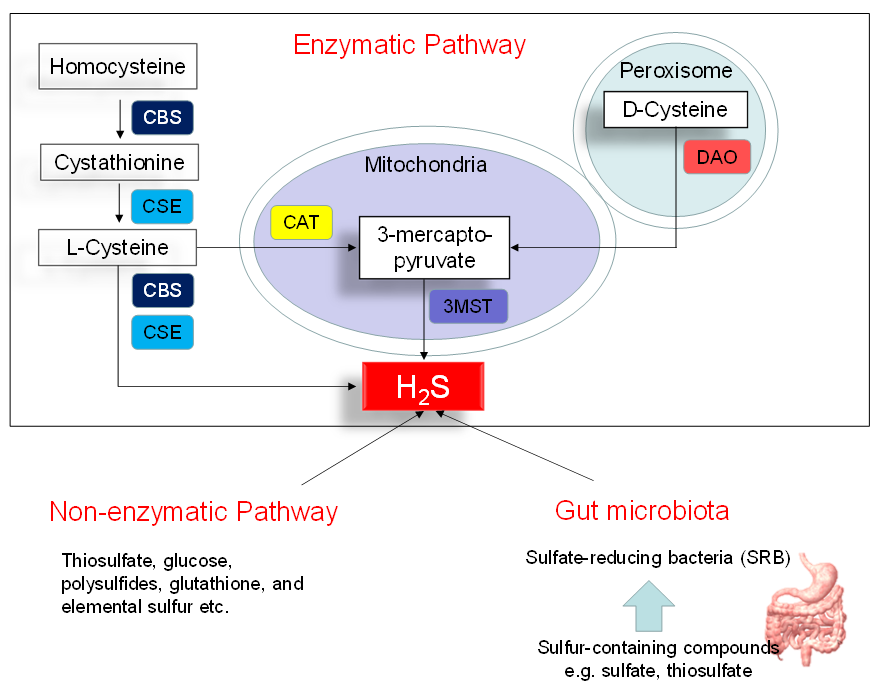

Figure 1 illustrates three major pathways of H2S synthesis, including enzymatic pathway, nonenzymatic pathway, and bacteria origins. Three enzymes have been identified to enzymatically generate H2S, cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulphurtransferase (3MST) [10]. CBS and CSE are cytosolic enzymes, but 3-MST is mainly existing in the mitochondria. l-cysteine is the principal substrate for both CBS and CSE to generate H2S. CBS and CSE can also produce H2S using other substrates. Homocysteine can be catalyzed by CBS to generate cystathionine, followed by CSE to produce l-cysteine. All of the above-mentioned H2S-generating enzymes are expressed in the heart and blood vessels [10,16]. In an alternative pathway, 3-mercaptopyruvate, the substrate for 3-MST to produce H2S, is provided by cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and D-amino acid oxidase (DAO). In the peroxisome, d-cysteine can be catabolized by DAO to generate H2S [17]. Besides the enzymatic pathway, H2S can be nonenzymatically produced through thiosulfate, glucose, polysulfides, glutathione, and elemental sulfur.

Another source of H2S is coming from the gut microbiota. Approximately fifty percent of fecal H2S is derived from bacteria. In the gut, sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB) obtain energy from the oxidation of organic compounds, reducing sulfate to H2S. Desulfovibrio account for 66% of all SRB in the human colon [18]. Other gut bacteria may also produce H2S by sulfite reduction, including species E. coli, Enterobacter, Salmonella, Klebsiella, Bacillus, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, and Rhodococcus [19]. Conversely, sulfur-oxidizing bacteria (SOB) reduces H2S via sulfur oxidation. The SOB members include genera Acidithiobacillus, Bacillus, Paracoccus, Pseudomonas, and Xanthobacter. In the gut, a huge quantity of H2S is oxidized by colonocytes to thiosulfate. The existence of thiosulfate in cecal venous blood not only reflects the detoxification of H2S but also the recycling of H2S.

In the circulation and tissues, free H2S can be scavenged and stored in the bound-sulfate and sulfane sulfur pools. Methylation and oxidation are two major mechanisms of H2S metabolism. H2S can be excreted in urine and flatus as free sulfate, free sulfide or thiosulfate.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of three major sources of H2S: enzymatic pathway, nonenzymatic pathway, and bacterial origins. Cystathionine β-synthase (CBS) catalyzes homocysteine to produce Cystathionine. Cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE) catalyzes cystathionine to form l-cysteine or l-cysteine to generate H2S. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (3MST) produces H2S from 3-mercaptopyruvate, which is generated by cysteine aminotransferase (CAT) and d-amino acid oxidase (DAO) from l-cysteine and d-cysteine, respectively. Another source of endogenous H2S is coming from nonenzymatic processes. The other source of H2S is derived from gut microbes, mainly by the sulfate-reducing bacteria (SRB).

2.2. The Role of H2S in the Pathophysiology of CVD

Multiple lines of evidence indicate that H2S plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of CVD. The first are reports on knockout mice lacking genes encoding for CSE, CBS, and 3-MST. CSE is the most relevant H2S-producing enzyme in the cardiovascular system. Mutant mice lacking CSE had decreased H2S levels in the serum, heart, vessels, and other tissues [20]. CSE knockout mice displayed hypertension, endothelial dysfunction, and accelerated atherosclerosis [20,21]. CBS-deficient mice developed endothelial dysfunction [22] and cerebral vascular dysfunction [23]. 3-MST knockout mice developed hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy [17]. Second, are observations that impaired H2S-generating pathways were found in CVDs, including atherosclerosis [24], coronary artery disease [25], stroke [26], and peripheral vascular disease [15].

Third, are studies of protein S-sulfhydration, a vital post-translational modification induced by H2S [9]. S-sulfhydration usually increases the reactivity of target proteins via formation of a cysteine persulfide to target proteins [9]. H2S is able to S-sulfhydrate Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1 (Keap1), specificity protein-1 (SP-1), nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) and interferon regulatory factor-1 (IRF-1) to regulate target gene transcription, which is crucial for the regulation of endothelial phenotypes, myocardial hypertrophy, mitochondrial biogenesis, oxidative stress, apoptosis and inflammation [9].

Fourth, several H2S-releasing drugs have demonstrated considerable promise for beneficial effects against CVDs in various animal models [7,8]. As reviewed elsewhere [7], several cytoprotective actions of H2S have been reported in the heart and vasculature. In the heart, the protective effects of H2S signaling was related to anti-inflammation, antiapoptosis, reduction of oxidative stress, and antifibrosis that leads to cardiac remodeling and functional improvements. In the vessels, H2S signaling can preserve endothelial NO synthase (eNOS)-derived NO production, while reducing oxidative stress, inflammation, fibrosis, and smooth muscle cell proliferation.

2.3. H2S Signaling in Various CVDs

Endothelial dysfunctions are associated with various CVDs, including hypertension, atherosclerosis, myocardial infarction, and the cardiovascular complications of diabetes. H2S can prime endothelial cells toward angiogenesis and contribute to relax vascular smooth muscle cells, and thereby reducing BP [27]. A deficit in H2S homeostasis is involved in the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction, while the application of H2S-releasing drugs to increase endogenous H2S level can restore endothelial function and antagonize the progression of CVDs.

Hypertension is a key risk factor for multiple CVDs. Like NO, H2S is a vasodilator. H2S has been reported to relax various blood vessels, such as the rat thoracic aorta, portal vein, and peripheral resistance vessels [28–30]. The involvement of H2S deficiency in hypertension has been examined in various animal models of hypertension, including the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) [31], the renovascular hypertensive model [32], Dahl salt-sensitive rats [33], and NO-deficient rats [34]. Conversely, several prior studies have shown the beneficial effects of exogenous and endogenous H2S on hypertension, as reviewed elsewhere [35]. However, little is known about whether these H2S-based therapies could be used as reprogramming interventions perinatally to reduce the vulnerability to developing cardiovascular programming in offspring.

ApoE knockout mice developed advanced atherosclerosis related to a decreased plasma H2S level and vascular CSE expression/activity, suggesting disturbance of the vascular CSE/H2S pathway plays a role in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis [36]. Additionally, a reduction in circulating H2S has also been noted in diabetic animal models and diabetic patients [37]. Conversely, H2S therapy proved beneficial in diabetes-accelerated atherosclerosis in diabetic mice [38]. In a rat model of myocardial ischemia–reperfusion (I/R), pharmacologic inhibition of CSE resulted in an increase in infarct size, whereas H2S replacement displayed myocardial protection [39]. Likewise, cardiac-specific overexpression of CSE in mice protects against myocardial I/R injury [40]. Summarizing, in clinical and preclinical studies of various CVDs, endogenous H2S production is diminished in these pathological conditions and H2S deficiency contributes to the progression of disease [7].

References

- World Health Organization. Cardiovascular Diseases (CVDs). 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds) (accessed on 27 December 2020).

- McGill, H.C., Jr.; McMahan. C.A.; Herderick, E.E.; Malcom, G.T.; Tracy, R.E.; Strong, J.P. Origin of atherosclerosis in child-hood and adolescence. J. Clin. Nutr. 2000, 72, 1307S–1315S.

- Hanson, M. The birth and future health of DOHaD. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2015, 6, 434–437.

- Thornburg, K.L. The programming of cardiovascular disease. Dev. Orig. Health Dis. 2015, 6, 366–376, doi:10.1017/s2040174415001300.

- Blackmore, H.L.; Ozanne, S.E. Programming of cardiovascular disease across the life-course. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 83, 122–130, doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.12.006.

- Tain, Y.-L.; Hsu, C.-N. Interplay between Oxidative Stress and Nutrient Sensing Signaling in the Developmental Origins of Cardiovascular Disease. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 841, doi:10.3390/ijms18040841.

- Li, Z.; Polhemus, D.J.; Lefer, D.J. Evolution of Hydrogen Sulfide Therapeutics to Treat Cardiovascular Disease. Res. 2018, 123, 590–600, doi:10.1161/circresaha.118.311134.

- Wen, Y.-D.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.Z. The Drug Developments of Hydrogen Sulfide on Cardiovascular Disease. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 1–21, doi:10.1155/2018/4010395.

- Meng, G.-L.; Zhao, S.; Xie, L.; Han, Y.; Ji, Y. Protein S-sulfhydration by hydrogen sulfide in cardiovascular system. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 175, 1146–1156, doi:10.1111/bph.13825.

- Kimura, H. The physiological role of hydrogen sulfide and beyond. Nitric Oxide 2014, 41, 4–10, doi:10.1016/j.niox.2014.01.002.

- Olas, B. Medical Functions of Hydrogen Sulfide. Advances in Applied Microbiology 2016, 74, 195–210, doi:10.1016/bs.acc.2015.12.007.

- Tain, Y.-L.; Joles, J.A. Reprogramming: A Preventive Strategy in Hypertension Focusing on the Kidney. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 17, 23, doi:10.3390/ijms17010023.

- Hsu, C.-N.; Tain, Y.-L. Hydrogen Sulfide in Hypertension and Kidney Disease of Developmental Origins. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1438, doi:10.3390/ijms19051438.

- Szabo, C. A timeline of hydrogen sulfide (H2S) research: From environmental toxin to biological mediator. Pharmacol. 2018, 149, 5–19, doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2017.09.010.

- Kanagy, N.L.; Szabo, C.; Papapetropoulos, A. Vascular biology of hydrogen sulfide. J. Physiol. Physiol. 2017, 312, C537–C549, doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00329.2016.

- Peleli, M.; Bibli, S.-I.; Li, Z.; Chatzianastasiou, A.; Varela, A.; Katsouda, A.; Zukunft, S.; Bucci, M.; Vellecco, V.; Davos, C.H.; et al. Cardiovascular phenotype of mice lacking 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. Pharmacol. 2020, 176, 113833, doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2020.113833.

- Shibuya, N.; Kimura, H. Production of hydrogen sulfide from d-cysteine and its therapeutic potential. Endocrinol. 2013, 4, 87.

- Linden, D.R. Hydrogen Sulfide Signaling in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2014, 20, 818–830, doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5312.

- Blachier, F.; Davila, A.-M.; Mimoun, S.; Benetti, P.-H.; Atanasiu, C.; Andriamihaja, M.; Benamouzig, R.; Bouillaud, F.; Tomé, D. Luminal sulfide and large intestine mucosa: Friend or foe? Amino Acids 2009, 39, 335–347, doi:10.1007/s00726-009-0445-2.

- Yang, G.; Wu, L.; Jiang, B.; Yang, W.; Qi, J.; Cao, K.; Meng, Q.; Mustafa, A.K.; Mu, W.; Zhang, S.; et al. H2S as a physiologic vasorelaxant: Hypertension in mice with deletion of cystathionine gamma-lyase. Science 2008, 322, 587–590.

- Mani, S.; Li, H.; Untereiner, A.; Wu, L.; Yang, G.; Austin, R.C.; Dickhout, J.G.; Lhoták, Šárka; Meng, Q.H.; Wang, R. Decreased Endogenous Production of Hydrogen Sulfide Accelerates Atherosclerosis. Circulation 2013, 127, 2523–2534, doi:10.1161/circulationaha.113.002208.

- Dayal, S.; Bottiglieri, T.; Arning, E.; Maeda, N.; Malinow, M.R.; Sigmund, C.D.; Heistad, D.D.; Faraci, F.M.; Lentz, S.R. Endothelial dysfunction and elevation of S-adenosylhomocysteine in cystathionine beta-synthase-deficient mice. Res. 2001, 88, 1203–1209.

- Dayal, S.; Arning, E.; Bottiglieri, T.; BöH.; Sigmund, C.D.; Faraci, F.M.; Lentz, S.R. Cerebral Vascular Dysfunction Mediated by Superoxide in Hyperhomocysteinemic Mice. Stroke 2004, 35, 1957–1962, doi:10.1161/01.str.0000131749.81508.18.

- Sun, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Yan, H.; Wan, H.; Li, X.; Chen, S.; Li, H.; Tang, C.-S.; Du, J.; Liu, G.; et al. Plasma H 2 S predicts coronary artery lesions in children with Kawasaki disease. Int. 2015, 57, 840–844, doi:10.1111/ped.12631.

- Zhang, M.; Wu, X.; Xu, Y.; Guizhen, A.; Yang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ao, G.; Cheng, J.; Jiaying, Y. The cystathionine β-synthase/hydrogen sulfide pathway contributes to microglia-mediated neuroinflammation following cerebral ischemia. Brain, Behav. Immun. 2017, 66, 332–346, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.07.156.

- Altaany, Z.; Moccia, F.; Munaron, L.; Mancardi, D.; Wang, R. Hydrogen sulfide and endothelial dysfunction: Relationship with nitric oxide. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 3646–3661, doi:10.2174/0929867321666140706142930.

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Wang, R. The vasorelaxant effect of H(2)S as a novel endogenous gaseous K(ATP) channel opener. EMBO J. 2001, 20, 6008–6016.

- Hosoki, R.; Matsuki, N.; Kimura, H. The Possible Role of Hydrogen Sulfide as an Endogenous Smooth Muscle Relaxant in Synergy with Nitric Oxide. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 237, 527–531, doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.6878.

- Cheng, Y.; Ndisang, J.F.; Tang, G.; Cao, K.; Wang, R. Hydrogen sulfide-induced relaxation of resistance mesenteric artery beds of rats. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2004, 287, H2316–H2323, doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00331.2004.

- Yan, H.; Du, J.; Tang, C. The possible role of hydrogen sulfide on the pathogenesis of spontaneous hypertension in rats. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004, 313, 22–27, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.081.

- Xiao, L.; Dong, J.-H.; Jing-Hui, D.; Xue, H.-M.; Guo, Q.; Teng, X.; Wu, Y.-M. Hydrogen Sulfide Improves Endothelial Dysfunction via Downregulating BMP4/COX-2 Pathway in Rats with Hypertension. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 1–10, doi:10.1155/2016/8128957.

- Huang, P.; Chen, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Yao, Q.; Huang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhu, M.; Wang, S.; Li, L.; et al. Down-regulated CBS/H2S pathway is involved in high-salt-induced hypertension in Dahl rats. Nitric Oxide 2015, 46, 192–203, doi:10.1016/j.niox.2015.01.004.

- Zhong, G.; Chen, F.; Cheng, Y.; Tang, C.-S.; Du, J. The role of hydrogen sulfide generation in the pathogenesis of hypertension in rats induced by inhibition of nitric oxide synthase. Hypertens. 2003, 21, 1879–1885, doi:10.1097/00004872-200310000-00015.

- Van Goor, H.; Born, J.C.V.D.; Hillebrands, J.-L.; Joles, J.A. Hydrogen sulfide in hypertension. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016, 25, 107–113, doi:10.1097/mnh.0000000000000206.

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Jin, H.; Wei, H.; Li, W.; Bu, D.; Tang, X.; Ren, Y.; Tang, C.; Du, J. Role of Hydrogen Sulfide in the Development of Atherosclerotic Lesions in Apolipoprotein E Knockout Mice. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2009, 29, 173–179, doi:10.1161/atvbaha.108.179333.

- Durante, W. Hydrogen Sulfide Therapy in Diabetes-Accelerated Atherosclerosis: A Whiff of Success. Diabetes 2016, 65, 2832–2834, doi:10.2337/dbi16-0042.

- Xie, L.; Gu, Y.; Wen, M.; Zhao, S.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Meng, G.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Hydrogen Sulfide Induces Keap1 S-sulfhydration and Suppresses Diabetes-Accelerated Atherosclerosis via Nrf2 Activation. Diabetes 2016, 65, 3171–3184, doi:10.2337/db16-0020.

- Zhuo, Y.; Chen, P.F.; Zhang, A.Z.; Zhong, H.; Chen, C.Q.; Zhu, Y.Z. Cardioprotective effect of hydrogen sulfide in ischemic reperfusion experimental rats and its influence on expression of surviving gene. Pharm. Bull. 2009, 32, 1406–1410.

- Calvert, J.W.; Jha, S.; Gundewar, S.; Elrod, J.W.; Ramachandran, A.; Pattillo, C.B.; Kevil, C.G.; Lefer, D.J. Hydrogen sulfide mediates cardioprotection through Nrf2 signaling. Res. 2009, 105, 365–374.Schulz, L.C. The Dutch Hunger Winter and the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 16757–16758.

- Stanner, S.A.; Yudkin, J.S. Fetal programming and the Leningrad Siege study. Twin Res. 2001, 4, 287–292.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/antiox10020247