Industrial heritage reflects the development track of human production activities and witnessed the rise and fall of industrial civilization. As one of the earliest countries in the world to start the Industrial Revolution, Belgium has a rich industrial history. Over the past years, a set of industrial heritage renewal projects have emerged in Belgium in the process of urban regeneration. In this paper, we introduce the basic contents of the related terms of industrial heritage, examine the overall situation of protection and renewal in Belgium. The industrial heritage in Belgium shows its regional characteristics, each region has its representative industrial heritage types. In the Walloon region, it is the heavy industry. In Flanders, it is the textile industry. In Brussels, it is the service industry. The kinds of industrial heritages in Belgium are coordinate with each other. Industrial heritage tourism is developed, especially on eco-tourism, experience tourism. The industrial heritage in transportation and mining are the representative industrial heritages in Belgium.

- conservation

- cultural regeneration

1. Introduction

The genesis of the notion of the cultural landscape is more likely laid on the multi-layered dynamic interrelations—both spatially and historically—of human intervention and natural processes to adjust its function to the changing community demands. Its understanding provides a way to bring the tangible and the intangible qualities of a shared environment and to enable its regeneration[1]. Industrialization generated significant changes in the urban and social landscape, including greater densities and the urbanization of the natural and rural environment; population moves and demand for reorganization of modern communities. However, over the past decades’ phenomena, such as the globalization, deindustrialization, the urbanization and the economic (re)conversion had profound effects on traditional industrial areas leading to a vast array of obsolete and former industrial facilities generated by them[2].

During the last decades, several studies have analyzed and documented the remnants of the industrial society [3][4] and emphasized the necessity of considering post-industrial landscapes in the city planning and the industrial heritage as a resource and an integral part of collective identity, while its preservation as ‘vital’ and vector for the historical identity.

At the beginning of the 21st century, it has been acknowledged that industrial heritage is understood and interpreted at the level of the landscape and of societies. That broader interpretation of the industrial heritage “focusses on the remains of the industry—sites, structures, and infrastructure, machinery and equipment, housing, settlements, landscapes, products, processes, embedded knowledge and skills, documents and records, as well as the use and treatment of this heritage in the present”. It should comprise “not only the remains of the Industrial Revolution, but also the traditional precursors from earlier centuries that reflect increased technical specialization, intensified productive capacity, and distribution and consumption beyond local markets, hallmarks of the rise of industrialization”[5].

The Industrial Revolution represented one of the most significant evolution in the history of mankind[6], important technological advances being registered in that period. In fact, the emergence of the Industrial Revolution is dated dynamically for each country and it is an on-going process in the 20th century i.e., quantitatively approaching; United Kingdom (1750/60), France (1780), Belgium (1790), Germany (1795), United States (1800), Russia (1850), Japan (1860), Brazil (1929), India (1947), China (1953) and so on. (Albrecht 2012). Therefore, each country needs to define and document its sub-frames of the industrialization process, though in the general framework of the global periodization system[5].

2. Overview of the Development of the Industrial Heritage in Belgium

After a general overview of the main terms of the industrial heritage and its related issues, the motivation and significance of the conservation and renewal of the industrial heritage have been established. A particular focus is provided for the country, as one of the most important parts of the industrial system in the world, Belgium.

In Continental Europe, Belgium is the first country, which absorbs and imports the U.K.’s Industrial Revolution achievements, in 1802 starting with the textile’s industrialization (cotton) in the region of Ghent and the wool in Verviers[7] Before this period, the country had an important industrialized activity focussed mainly on trading; on the other hand, in the region of Flanders, the textile production had been flourished, while in the Walloon region we could observe mainly the coal mining; these two branches have been the keys for industrialization in Belgium for many years.

2.1. Overview of the Industrial Development in Belgium

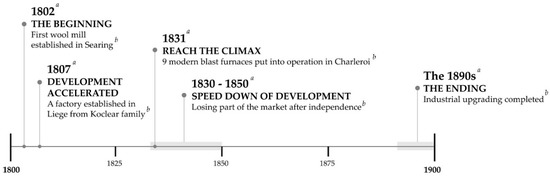

Belgium has a rich industrial past. An important landmark for Belgian heritage to mark out has been the first steal engine, inspired by T. Newcomen, which was succeeded by another one around the regions of Mons and Charleroi. During the period of the French domination (1795 to 1814), coal was mainly mined in the Borinage surroundings (province of Hainaut). From 1795 to 1814, coal was mined in the Borinage (southwest of Mons) to feed Paris via the river network, under the French administration. Based on the foundation of the French Revolution, the Industrial Revolution of Belgium was the engine[8]. Around the 1800s, William Koclear set up the first factory in Seraing, near Liege, from which the Belgian Industrial Revolution began (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Significant landmarks in the history of industrial development in Belgium (a. Date and event derived from Miklas Tich and Roy Porter (1996). b. Stage was defined by the author and references based on historical events).

The regional distribution of the Industrial Revolution center in Belgium is presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Belgian Industrial Revolution centers.

| District | City a | Field b | Representative Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liege | Verviers | Industry promotion | Machinery |

| Charleroi | Mons | Industry promotion | Coal |

| - | Ghent | Industry promotion | Textile |

| - | Antwerp | Service | Port |

| - | Brussels | Service | Capital |

a. City and its representative industry derived from Miklas Tich and Roy Porter (1996). b. Field was defined by the authors.

But Belgian heavy industry took off during the Dutch rule of the country from 1815 to 1830. Notwithstanding, Belgian heavy industry took off during the Dutch rule of the country of the period 1815 to 1830. At the same period, William I, supported by J. Cockerill, exploited the activities around the textile machinery. At the end of the 18th century. Due to the introduction of the steam engine. Belgium was the first continental country into the Industrial Revolution. It started by industrializing the textile industry in Ghent (cotton) and Verviers (wool).

As the first industrialized country on the European continent, Belgium quickly followed in Britain’s footsteps. However, only by the end of the 19th century, did industry and industrialized work become more important than agriculture and artisanal production. This becomes clear when looking at the employment figures. In 1846, the industrial census noted 90,000 industrial workers, or 4% of the total working population, whereas, by 1910, the industry employed nearly half of the working population. This perception of Belgium being a rapidly industrializing country was mainly due to coal mining and the metal and textile industry; the remains of Belgium’s industrial past are characterized by a great diversity [9][22]. Before this period, Belgium was a traditional industrial country in Europe[10].

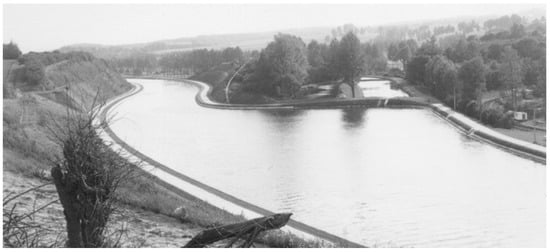

The first Industrial Revolution witnessed clusters of industrial activities located near the natural resources and raw materials. Liège already had exploited proto-industry with forges and gun manufacturing, while Charleroi was predominated in nail factories, so they were able to embrace coal mining, steel, and other metal activities extensively, which led to population movements from the countryside for job opportunities. From the other side, the canal of Brussels-Charleroi was inaugurated in 1832 by linking the mines to the North Sea through the city of Brussels (Figure 3)[11].

Figure 3. The Brussels-Charleroi canal, 1966.

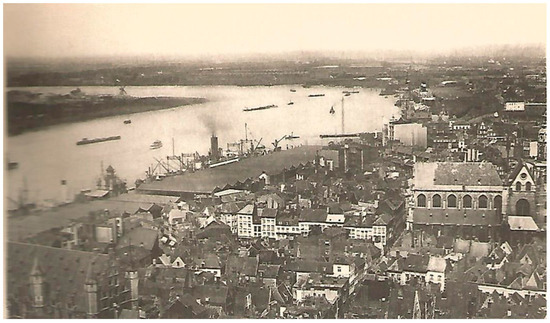

At the same time, the center of Belgium, and in particular the part of its connection with the city of Antwerp, was gaining momentum with new industrialized activity. Antwerp and the port of Liege were gradually becoming the key logistics pivot of Belgium even for the whole of Western Europe (Figure 4) [12][25].

Figure 4. Antwerp—an industrious historic city, 1863.

After the First World War, the arrival of Ford and General Motors to Antwerp and Renault to Brussels was an important step for the industrialized activities of Belgium, while in 1917 the coal finding in Limburg (eastern Belgium) marked a new era. However, this evolution was ceased during the internal crisis of the 1930s[11].

After the Second World War, the ‘heavy’ industrialized and intensive activities in the Walloon region seemed competitive; nonetheless, very soon the weaknesses and the need for modernization became apparent [11].

3.2. Inspection and Research Institutions for Industrial Heritage

The industry was engine by economic power primarily. However, the development path of industrial heritage was influenced by industrial heritage inspection and research institutions[13], for instance, the UNESCO assessed a set of industrial heritage list to protect the industrial sites in the range of the world. The industrial sites on the list can take higher-level protection than before. To have a comprehensive understanding of the development status of industrial heritage in each region, it is also necessary to understand the status quo of their own internal industrial heritage research institutions. The Industrial Revolution of the U.K. spends 50 years to spread into Belgium. Nonetheless, Belgium started an industry heritage investigation, followed by the U.K. tidy [14].

In 1970, Georges van den Abeelen created the industrial archaeology center, it was a trigger for industrial inspection and record subject in Belgium [12]. Meanwhile, it was where the exhibition man and machine were held in Brussels two years later supported by historians and archaeologists from different fields.

In Flanders, the VVIA (1978) had an important role on the national level and eventually represented the whole country at the issue of inspection and recording of the Belgian industrial heritage[15]. After an extensive analysis of research projects, and reports in 1984, based on the VVIA, the PIWB and TICCIH Belgium were established [16] as a triangular relationship. This is a unique situation in Western European countries (Table 2). Each institution is doing inspections and records for industrial heritages in their regionals.

Table 2. Schedule of main industrial heritage inspection and research institutions in Western European countries.

| Location | Organization | Abbreviation a | Established Time a |

|---|---|---|---|

| The U.K. | Association for Industrial Archaeology | AIA | 1973 |

| German | The International Committee for the Conservation of the Industrial Heritage Deutsch | TICCIH Deutsch | 1978 |

| France | Le Comité d’information et de liaison pour l’archéologie, l’étude et la mise en valeur du patrimoine industriel | CILAC | 1979 |

| The Netherlands | Federatie Industrieel Erfgoed Nederland | FIEN | 1984 |

Take the PIWB as an example, it was established at the time of the rise of industrial heritage protection in Belgium. In the early stage, its work mainly focused on the publicity of the restored sites and promoting the social protection of potential sites. With the advancement of research and the development of industrial tourism, the work of the PIWB has become diversified and the related fields have become wider. They began to pay attention to the relationship between industry and human beings. Meanwhile, the concept of industrial archaeology was expanding considerably, calling for vigilance extended to other fields—ancestral technologies and proto-industries, tangible as well as intangible heritage, oral history.

3.3. Industrial Heritage in Belgium

As previously mentioned, ‘industrialization’ has had different impacts leading to significant changes in the urban, social and cultural environment (for instance, greater density and more compact urban areas, population moves, etc.)., thus contributing to the typical 20th-century urban settlement[17]. The classification of territory as ‘industrial’ implied a qualitative perception, in which territory and industrial infrastructures were analyzed from a functional, cultural, and historic angle[18]. In this sense, and according to Borsi [19] the industrial landscape is “the landscape resultant from a thoughtful and systematic activity of man in the natural or agricultural landscape with the aim of developing activities related to the industry”. This definition enabled the recognition of an entire landscape as a single “element”, allowing the expansion of the conception of its conservation to accommodate “recognized patterns of activity in time and place” [20].

Based on the ERIH, this research categorized the industrial heritage of Belgium (Table 3). Listing the most important elements of the Belgian industrial heritage, we observe that Belgium scatters its heritage in every corner with a variety of categories (Table 4).

Table 3. Main categories of the Belgian industrial heritage.

| Heritage Category |

|---|

| Industry and War |

| Iron and Steel |

| Landscape |

| Mining |

| Production and Manufacturing |

| Water |

| Communication |

| Textiles |

| Service and Leisure Industry |

| Paper |

| Transport |

Table 4. Main elements of the Belgian industrial heritage.

| dustrial Heritage | Description | Illustration |

|---|---|---|

| Blégny Mine | Located between Liège and Maastricht, Blegny-Mine is one of the four authentic coal mines in Europe with underground galleries accessible for the visitors through the original shaft |  |

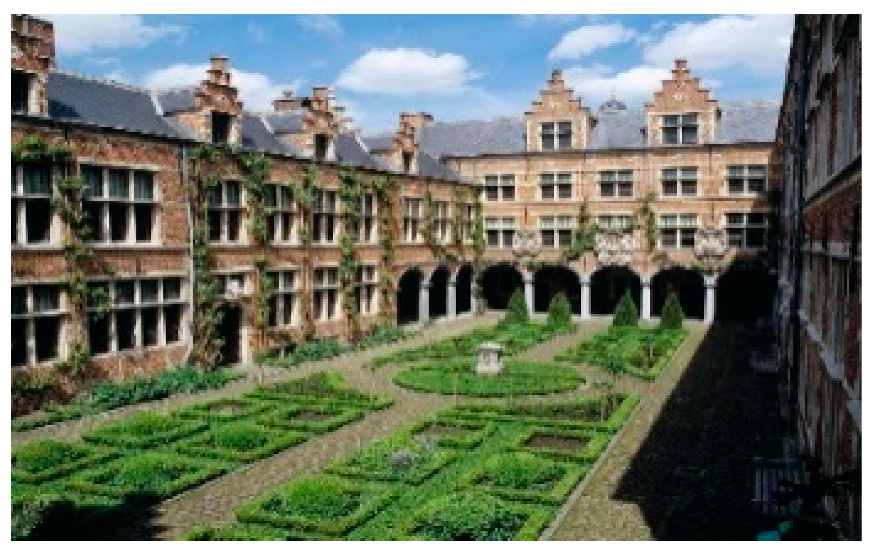

| Museum Plantin-Moretus | The world’s oldest surviving printing works is a work of art in itself |  |

| Val St-Lambert | The Belgian glassware that took the world by storm a century ago |  |

| Speelkaartmuseum | The huge scale of machines once required to make playing cards |  |

| Le Bois du Cazier | A slag heap in archetypal post-industrial Charleroi |  |

| Canals of the Borinage | Remarkable ship-lifts, old and new |  |

| Centre Touristique de la Laine et de la Mode | A fascinating textile museum |

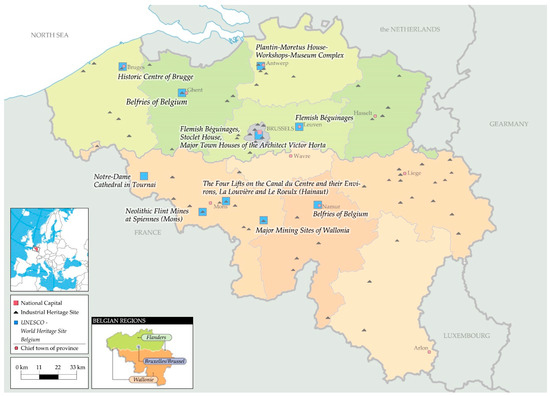

Most of them were renewed properly and 6 of them were added to the world heritage (UNESCO) (Figure 5)[21]. On the one hand, redeveloping these heritages to cultural or other types of activities through adaptable architectonic interventions, while on the other hand, surveying and analyzing their conservation and renewal paths are a benefit for urban regeneration and the science of human settlement. UNESCO promotes at the same time the identification, conservation, and preservation of the world heritage as an outstanding value to humanity. Europe is particularly well represented on the list of heritage sites, as is Belgium (Figure 6)[22].

Figure 5. The UNESCO-world heritage and Industrial heritage landmarks in Belgium.

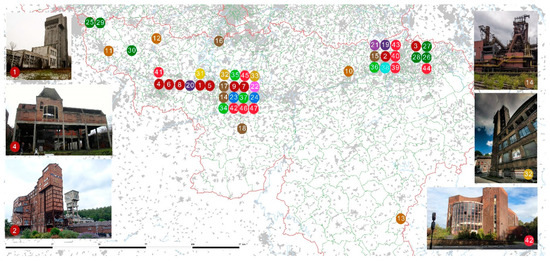

Figure 6. Industrial heritage in Wallonia counting.

In addition, we can identify many industrial wastelands in the Walloon territory. Yet, there has not been a detailed existing inventory of an architectural and heritage interest but only according to several categories resulting from past production. We can easily see that the latter is located on the Croissant Houiller with the major urban centers of Charleroi and Mons (Figure 6).

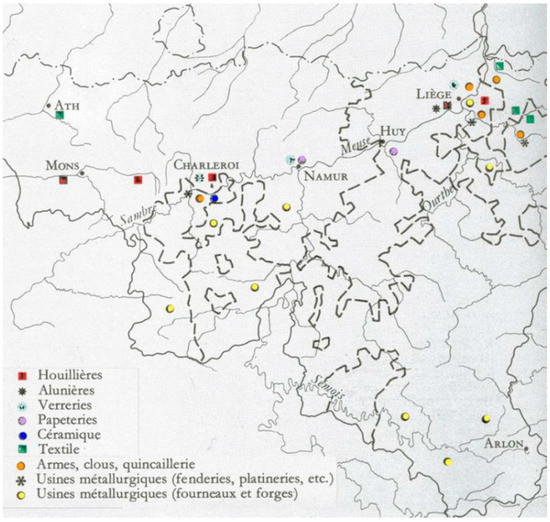

3.3.1. Pre-Industrialization Heritage

The origins of the industrialized activities in Belgium find their earliest traces already back to the late Middle Ages, where industries prosper with some of the resulting production exported outside the Walloon territory, for instance, Dinant, which was an important center for brass working, and focused on the raw materials trade from England and Germany. From the other side, in Nivelles and in the west of the Comté de Hainaut, the linen industry was experienced, as well. Furthermore, master ironworkers developed new processes with records back to 1320. During the 16th century (noticed as the ‘metalworking period’), the prosperity, especially in Wallonia continued, where one of the densest steel regions of the western Europe was established; during the same period, two hundred factories operated in Wallonia (Figure 7), while the coal production was increased considerably in Liège. At the same time, the textile industry began its expansion in the region of Verviers and new glass industrial activity was developed in Hainaut and part of Brabant. Later, during the 17th century, the war struck all business activities, and with its end, the manufacture of nails, gunpowder, weapons, and coal export were increased, while the glass industry from 1650 and onwards was developed around Charleroi and Jumet[23].

Figure 7. Geographical distribution of Walloon industries, 1680.

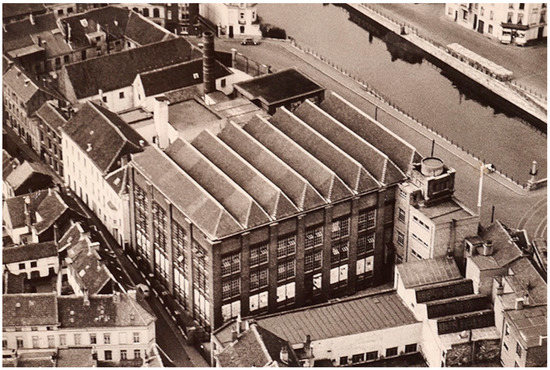

The earlier industry heritage was called pre-industrialization heritage, the representation in Belgium is the wool textile factory heritage [8][24]. During this period, the country has developed a vibrant trading tradition focused basically on the textile production, which flourished in Flanders and the iron processing in Wallonia. These key branches had been the prerequisites for the industrialization era, which followed. Indeed, Belgians maintained intensively the connection with Great Britain and in 1720 the first steam engine went into action near the region of Liège, a model inspired by T. Newcomen which used to draw out wastewater from coal mining. This engine was succeeded later by another one around the areas of Mons and Charleroi boosting rapidly the coal and steel industrial activity. Later, in 1792, the country was dominated by Napoleon, who introduced the trade freedom and the market was flourished up in France[25].In the middle ages, the regions of Flanders and Brabant were the centers of the production of wool fabrics, and the division of labor was very meticulous. After the 16th century, Belgium’s cottage industry became more and more prosperous and became the real foundation of Belgium’s industrial development in the 18th century, for instance, the museum of industry (Ghent) (Figure 8)[26].

Because of its developed textile industry, Ghent developed from the end of the eighteenth century into an important center of the textile industry in Belgium [27]. During this period, the factory buildings were almost re-built from monasteries. Because the textile machine needs a bright and spacious space for running.

3.3.2. Industrialized Period from 1802 to the 1890s

The year 1802 is generally regarded as the beginning of the modern industry in Belgium[28]. After that, trade volume and production capacity stimulated each other and entered a period of rapid growth. At the end of the 19s, Belgium appeared numerous beer factories, giant bridges, transportation hubs, and so on, for instance, before the First World War, Belgium had more than 3000 beer factories [29]. Nonetheless, due to the large-scale expansion in this period, the design and construction of industrial buildings had not gone through too much serious thinking and deliberation. Almost no one studies what materials should be used and what forms should be adopted for these buildings. Therefore, in this period, the industrial buildings had a similar appearance to general public buildings[28].

After the Belgian Independence Movement. The Belgian government attempted to raise the level for Antwerp in international cross-border trade, compared with Rotterdam and Hamburger[30][31]. They built several transportation connection facilities with other central industrial cities in Antwerp. Established a sea transportation base and raw material import center for Wallonie’s heavy industry.

According to this condition, Antwerp has a large number of industrial constructions, including warehouses, canals, railways, shipyards, dockyards, and so on. In the first half of the 20th century, two World Wars broke out, which objectively promoted the rapid discrepancy transformation of the Belgian industry between Wallonie and Flanders[32]. After the end of this period, the Belgian industry building got a wide range of influence from internationalization. It began to try to use new building materials, including prestressed reinforced concrete, steel, glass, and so on. The style of industrial buildings and the use of materials began to connect with the world.

3. Conservation and Renewal of the Industrial Heritage and Its Importance towards the Cultural Regeneration

An important reflection of the industrial heritage is its conservation and the strategies towards its renewal. In the protection of the transportation facilities, a few of them were redeveloped into experiential museums for the public. To ensure the integrity and authenticity of the railway heritage, and to keep it in a stable environment without over modernization. The care for the conservation and the capitalization of the cultural resources indicates a given society’s degree of interest and an important connection with its past and history. Urban regeneration of former industrialized areas is also meant to avoid derelict areas and to promote strategies towards their conversion and exploitation aiming to display them as patrimony assets. Arguably, the conversion of industrial sites is a complex and an intangible aspect, which demands knowledge, expertise, and understanding of the efficient strategies of heritage conservation towards the sustainable revitalization of these sites. It is important to study the perspectives of the reconversion and the reuse of the formerly industrialized structures obtaining a new and multi-dimensional role as a source of economic stability and unique cultural identity. In this section, we provide an overview of interesting reconversion stories with a particular focus on our case-study of Belgium.

3.1. An European Overview of Interesting Examples

As we already explained, during the decade of the ‘70s the continuous and rigid decline of the industrial activities in many European countries left a significant number of buildings, sites, and former working places abandoned. Nonetheless, the idea towards their urbanization renewal has developed across Europe recently aiming to improve their living conditions and redevelop them through a gentrification process.

In this sub-section, some emblematic projects of famous rejuvenations around Europe are discussed[33]:

-

Matadero (Madrid, Spain): formerly a slaughterhouse and meat market inaugurated in 1924 and it remains an interesting architectural reference of industrial’s site transformation in Spain along with a renovation process towards its transformation into parks and promenades. Nowadays, Matadero is dedicated basically to art, design, and literature and it accommodates exhibitions of a great variety.

-

Wuk (Vienna, Spain): former locomotive factory (in 1855), turned into a cultural place (beginning of the 80s) promoting basically cultural activities with a variety of activities dedicated to contemporary art, etc.

-

Kaapeli (Helsinki, Finland): former cable factory and a production site for Nokia Corporation. Today, the site has the function of a multimodal cultural center and accommodates three museums, twelve galleries, theatres, art schools, and other artistic disciplines.

Other interesting study areas of similar cases, such as the mining-related heritage tourism are found in Germany (Mining Museum with approximately 40,000 visitors); in Austria (Mine at Eisenerz opened in 1986 operated by a local company accommodates around 80,000 visitors per year) or in Italy the Talc and Graphine mine (Scopriminiera, 70 km from Turin) which is transformed into a museum, as well. Other examples of European cases and their renewal are found in textile industry heritage, for instance, the Audax Museum in the Netherlands, which became a ‘bridge’ of the past textile production, the present, and the future and receives many visitors throughout the year; or even the railway heritage tourism, which is quite widespread, especially for countries, such as the England[34][35].

3.2. A Focus in the Case of Belgium

In Belgium, not only locomotives and carriages, but also railways and stations were got a reservation, for instance, the Tramway Historique Lobbes-Thuin railway heritage which is one of the most aging tourism railways in Western Europe. Managing by ASVI. It includes trains, railways, stations, and service facilities. Tourists to the line can inspect the vehicles not currently in use in a large showroom (Figure 9)[36].

Figure 9. Showroom for vehicles display.

They can also take an old train through picturesque wooded countryside, passing the notable churches and terraced gardens and a belfry at Thuin (Figure 10)[36].

Figure 10. Train experience.

When talking about industrial heritage in Belgium, the mining heritage is an inextricable part. In this study, Wallonie is the representative case in Belgium. In 1720, a new air pressure pump was installed in the Liege coal mine area for the first time [37]. In 1814, Mons-Charleroi had an extraordinarily burgeoning in mining with more than 400 mining areas. The annual output had reached 1 million tons. This situation brought oceans of mining heritages after the industry-transforming[38]. Nonetheless, due to its huge area of land, and the lack of decoration outside, this phenomenon led to the rejection of the people for a long period. A typical mining heritage influences people is even more than that of a medieval church because this mining played an important role in promoting social development and economic prosperity.

Instead of demolishing these heritages, it is better to transform and renewal them, retain the imprint of industrial development, and make them continue to serve modern life. Therefore, the Belgian society reusing and conserving them selectively and gradually. Some of their pits have formed their microclimate, and many are rich in animal and plant life[39]. It is a route to preserve and develop ecotourism projects. Tourists can explore their unique landscape and eco-system while climbing the pit, and also experience the industry history in Belgium by tourists themselves [40]. Such as the project the trail of the pit in the Walloon region, a kind of reusing in eco-tourism for industrial heritage, which became very popular in Belgium[41].

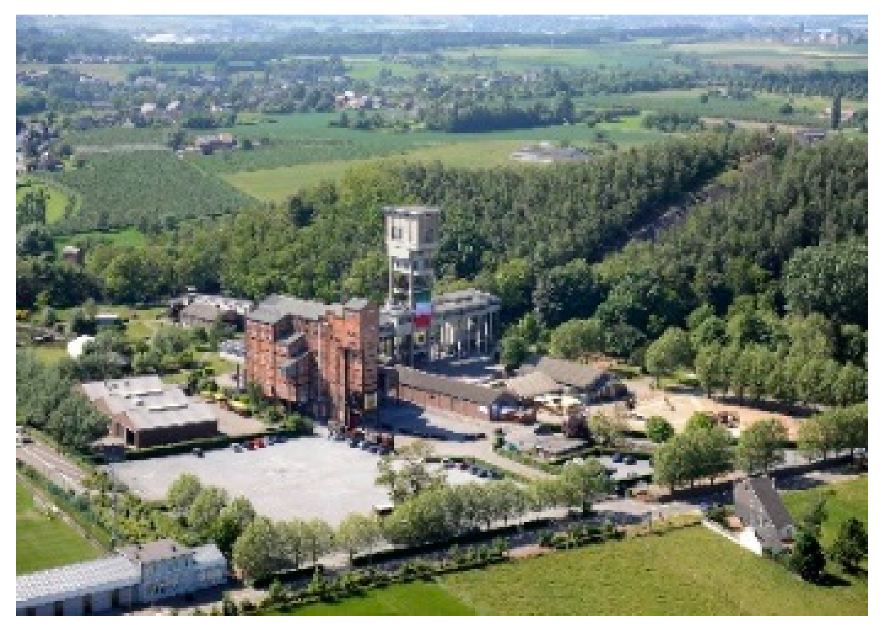

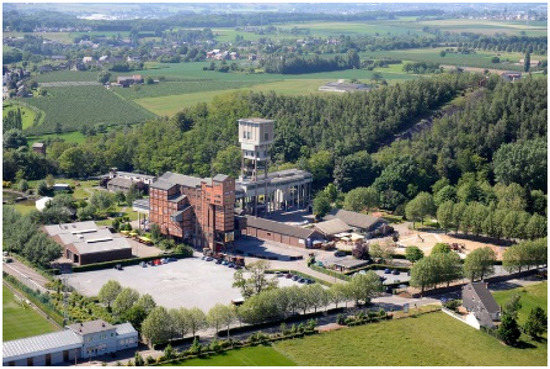

Complementary to the common status of the conservation brownfield, the reconstruction of the ecological environment. There are also challenging and bold attempts. A large number of mines, tunnels, factories, and industrial facilities have become the material evidence for reserving the history of Belgium, for instance, the Blegny-Mine world heritage site museum which has been listing in the UNESCO world heritage sites (Figure 11)[42][43].

Figure 11. Aerial view of Blegny-Mine.

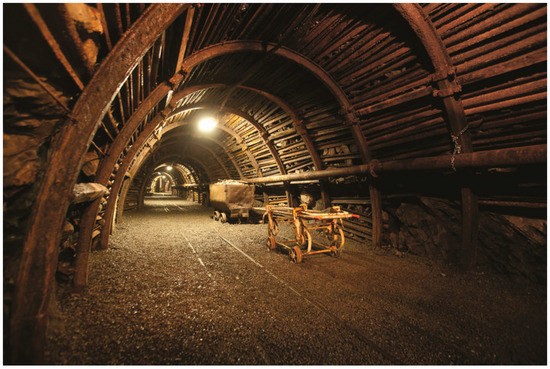

When it closed in 1980, the Blegny-Mine was the oldest and last remaining mine in the Liege district. The famous feature of that is tourists can experience the whole mining progress by old facilities. Like how workers did before 200 years. The museum has an intact mining assembly line. Tourists can go underground by a cage (Figure 12)[43].

Figure 12. The underground operation area of Blegny-Mine.

Understanding the whole mining process by various forms of tour introductions, for instance, infrared-guided audio tours, lighting effects, animations, authentic reconstructions, and an exciting media show that stages the origin of the coal. The museum has multifaction facilities, tourists can not only take a scientific tour but also can take a walk on the stone heap, playgrounds, a petting zoo, a mini-train, or even a boat trip to Liege. It offers various tourism choices for families. As one of the 4 major mining sites of Wallonia recognized the UNESCO world heritage, and a site of regional industrial route “Route of Fire”, Blegny-Mine plays an important role in the industrial heritage system in Belgium.

Belgium’s industrial heritage protection takes various types of industrial museums as an important way of protection, preserving the original state of industrialization, reflecting and inheriting the achievements of industrial civilization. As a new form of special tourism with historical nostalgia and popular science experience as the main motivation and the integration of industry and tourism, industrial tourism in Belgium has not developed for a long time and has the smallest area of territory. However, compared with the traditional industrial tourism powers surrounding, Belgium has the highest density of industrial heritage tourism projects (Table 5).

Table 5. Industrial tourism case density ranking of Belgium’s surrounding countries in ERIH.

| Ranking | Country | Case | Area of the Territory (km2) | Case Density (Case/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Belgium | 68 | 30,528 | 0.00222 |

| 2 | The Netherlands | 66 | 41,865 | 0.00157 |

| 3 | The U.K. | 380 | 244,100 | 0.00155 |

| 4 | Germany | 375 | 357,022 | 0.00105 |

| 5 | Portugal | 37 | 92,212 | 0.00040 |

| 6 | Italy | 105 | 301,333 | 0.00034 |

| 7 | France | 146 | 672,834 | 0.00021 |

| 8 | Spain | 102 | 506,000 | 0.00020 |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/info12010027

References

- Antrop, M. Why landscapes of the past are important for the future. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 70, 21–34.

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T. Recovering derelict industrial landscapes in Portugal: Past interventions and future perspectives. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Energy, Environment, Ecosystems & Sustainable Development, Agios Nikolaos, Greece, 24–26 July 2007; pp. 116–121.

- Vogt, K.C. The post-industrial society: from utopia to ideology. Work Employ. Soc. 2016, 30, 366–376.

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018.

- Zacharopoulou, G. Diachronic exploitation of landscape resources‒tangible and intangible industrial heritage and their synthesis suspended step. In Proceedings of the XVIth International TICCIH Congress, Lille, France, 6–11 September 2015.

- Andrei, R. Industrial building conversion-The Poaching of an already poached reality. Bul. Inst. Politeh. Din Lasi. Sect. Constr. Arhit. 2012, 58, 157.

- Dhondt, J.; Bruwier, M. The Industrial Revolution in the Low Countries 1700–1914. In The Emergence of Industrial-1 The Fon-tana Economic History of Europe; Fontana Publisher: Roermond, The Netherlands, 1973.

- Guoxue, F. On the industrial revolution in Belgium in the 19th century. J. Anhui Univ. 2004, 31-36. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2004&filename=ADZS200402005&v=unxC0DyvvaJo3v4hKrmPvvtqTDMZm9PCmd7eHNGNyY1HcjhD8SvizoizOf5zassU (accessed on 25.May.2020).

- Vander Stichele, A.; Januarius, J.; Vereenooghe, T.; Debo, R.; De Vooght, D. Industrial Heritage in Flanders (Belgium): Public Perception and Participation Rates. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/download/41039469/paper_TICCIH.pdf (accessed on 11.August.2020).

- Alter, G. Work and income in the family economy: Belgium, 1853 and 1891. J. Interdiscip. Hist. 1984, 15, 255–276.

- Galindo, G. How 200 Years of Industry Shaped Belgium’s Identity. Availabe online: https://www.brusselstimes.com/news/eu-affairs/139811/europol-takes-europe-wide-action-against-online-hate-speech/ (accessed on 15.July.2020)

- Van den Abeelen, G. Industrial Archeology; The Federation of Belgian Enterprises: Burssels, Belgium, 1973.

- Alfrey, J.; Putnam, T. The Industrial Heritage: Managing Resources and Uses; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003.

- lubeckett, R. History of Industrialization; Shanghai Translation Press: Shanghai, China, 1983; Volume 2.

- Cenci, J. From factory to symbol: Identity and resilience in the reuse of abandoned industrial sites of Belgium. Hist. Environ. Policy Pract. 2018, 9, 158–174.

- Patrimoine Industriel Wallonie-Bruxelles; Genicot, L.-F.; Hendrickx, J.-P. Wallonie-Bruxelles: Berceau de L’Industrie sur le Continent Européen; Patrimoine Industriel Wallonie-Bruxelles: Charleroi-Marcinelle, Belgium, 1990.

- Loures, L. Industrial Heritage: the past in the future of the city. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2008, 4, 687–696.

- Tandy, C. Industria y Paisaje; Instituto de Estudios de Administración Local: Madrid, Spain, 1979.

- Borsi, F. Le Paysage de L’Industrie; Archives d’Architecture Moderne: Bruxelles, Belgium, 1975.

- Meinig, D.W. The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes: Geographical Essays; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1979.

- Lusiani, M.; Zan, L.; Swensen, G.; Stenbro, R. Urban planning and industrial heritage–a Norwegian case study. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 3, 175–190, doi:10.1108/JCHMSD-10-2012-0060.

- Hospers, G.-J. Industrial heritage tourism and regional restructuring in the European Union. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2002, 10, 397–404.

- First Transformations and Expansion (18th Century). Available onlie: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/193995/1/978-90-485-4448-6.pdf (accessed on 15.December.2020).

- Abad, C.J.P.; Pino, J.M. Conservation, management and tourist use of pre-industrial heritage. Identification of Spanish experiences from a territorial analysis. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–22, doi:10.15640/jthm.v3n1a1. Availabe online: http://jthmnet.com/vol-3-no-1-june-2015-abstract-1-jthm (accessed on 01.June.2020.).

- On the industrial history of belgium. European route of industrial heritage. Available from: https://www.erih.net/how-it-started/industrial-history-of-european-countries/belgium (accessed on 07.June.2020).

- Munsters, W. Cultural tourism in Belgium. In Cultural tourism in Europe; CAB International: Wallingford, UK, 1996; pp. 109–126.

- Boussauw, K. City profile: Ghent, Belgium. Cities 2014, 40, 32–43.

- Jacobs, S.; Notteboom, B. Photography and the spatial transformations of Ghent, 1840–1914. J. Urban Hist. 2018, 44, 203–218.

- Shiyan, H. Overall of the beer industry in Belgium. Liquor-Mak. Sci. Technol. 1996, 1, 65.

- Winter, A. Migrants and Urban Change: Newcomers to Antwerp, 1760–1860; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015.

- Loyen, R.; Buyst, E.; Devos, G. Struggling for Leadership: Antwerp-Rotterdam Port Competition Between 1870–2000; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Eichengreen, B. 2 Institutions and economic growth: Europe after World War II. In Economic Growth in Europe since 1945; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 38–72.

- A Second Life for Industrial Heritage Sites in EUROPE. ASEF Culture360, 18 June 2015.

- Bernard Lane. Industrial Heritage and_AgriRural Tourism in Europe a review of their development socio-economic systems and future policy issues. Available online:

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/etudes/join/2013/495840/IPOL-TRAN_ET(2013)495840_EN.pdf (accessed on 07.June.2020).

- Wikipedia. ASVi Museum—Tramway Historique Lobbes-Thuin. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.og/wiki/ASVi_museum (accessed on 05.June.2020)

- Lintsen, H.; Steenaard, R. Steam and Polders. Belgium and the Netherlands, 1790–1850. Tractrix: Yearb. Hist. Sci. Med. Technol. Math. 1991, 3, 121–147.

- Teich, M.; Porter, R.; Gustafsson, B. The Industrial Revolution in National Context: Europe and the USA; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996.

- Lemoine, G. Development of germignies-nord slag heap (north), and the preservation of its fauna, flora and habitats by extensive grazing. Bull. Soc. Bot. N. Fr. 2011, 64, 17–26.

- Melin, H. Loos-en-Gohelle, du noir au vert. Multitudes 2013, 52, 59–67.

- Zhang, J.; Cenci, J.; Becue, V.; Koutra, S.; Ioakimidis, C.S. Recent evolution of research on industrial heritage in Western Europe and China based on bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5348.

- Nyns, S.; Bedoret, J.; Crespin-Noël, E.; Saint-Viteux, F. Le site du Gosson, de la friche minière à un parc urbain et pédagogique nature admise? In Les Friches Minières: Paysage Culturel et Enjeu de Développement Rural. Regards Croisés Entre Bucovine et Wallonie; Atelier des Presses: Liège, Belgium, 2017; pp. 161–183.

- Blegnymine.be. Available online: https://www.blegnymine.be/en/multimedia/coal-mine (accessed on 29.June.2020).