2.4.1. Metformin-Induced Inhibition of Hyperandrogenism and Normalization of the Steroid Hormones Balance

One of the main mechanisms of the restorative effect of MF on ovarian function, ovulation and pregnancy in PCOS women mediates through the pronounced antiandrogenic effect of MF, both in monotherapy and in combination with other drugs [

141,

152,

171,

172,

173,

174,

175,

176,

177,

178,

179]. One-year treatment of overweight PCOS women with MF (1700 mg/day) reduced the levels of free testosterone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and androstenedione, and significantly weakened the signs of hirsutism. This effect of MF was strongly associated with a decrease in the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) and an improvement in glucose tolerance, but was weakly associated with a decrease in the body weight, which indicates a main contribution of a decrease in IR and hyperinsulinemia to the antiandrogenic effect of MF [

180]. An antiandrogenic effect was demonstrated in the treatment of overweight and obese adolescents with MF (1000–2000 mg/day), and was accompanied by a significant decrease in IR [

152,

173,

174,

176,

177]. MF reduced both the basal and gonadotropin-stimulated testosterone levels, and these effects were observed even with short-term MF treatment. The administration of MF for two days to PCOS women caused a decrease in their testosterone levels stimulated by luteinizing hormone (LH). This effect was not due to a decrease in the body weight and the changes in metabolic indices, pointing to potential direct influence of MF on steroidogenic activity in ovarian cells [

181].

In PCOS, the severity of IR is positively correlated with the severity of HA and dysregulations of the ovulatory cycle. The PCOS women with oligomenorrhea and without HA usually do not have IR, while the PCOS women with oligomenorrhea and HA often show significant signs of IR [

182]. In turn, in PCOS women with regular ovulatory cycle, IR was less pronounced than in women with PCOS and irregular or no ovulation [

183].

The inhibitory effect of MF on the production of steroid hormones by ovarian cells was demonstrated in the in situ experiments using different cell lines [

94,

184,

185,

186]. Cultured human ovarian cells grown in the presence of MF, showed a decrease in production of basal and gonadotropin- or insulin-stimulated steroid hormones. Similar effects were shown for progesterone and estradiol in granulosa cells and androstenedione in theca cells. Inhibitory effect of MF was dose-dependent and most pronounced in the measure of suppression of hormone-stimulated steroidogenesis [

185]. MF (10 mM) treatment of bovine granulosa cells isolated from small follicles led to a decrease in both the basal and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH)- and IGF-1-stimulated production of progesterone and estradiol [

186].

When deciphering the mechanisms of the inhibitory effect of MF on steroidogenic activity in the ovaries, a key role is assigned to stimulation of AMPK, and the triggering of AMPK-dependent pathways in ovarian cells [

94,

186,

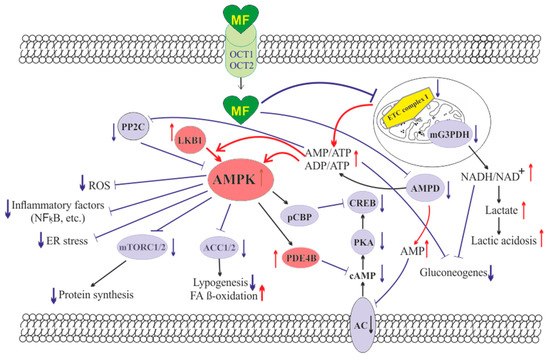

187] (). The mechanisms of AMPK activation in ovarian cells are the same as described in the

Section 2 above, and are triggered by MF-induced inhibition of electron transport chain in mitochondrial respiratory complex I [

188]. It is worth noticing that in humans, other mammals and birds (cows, goats, sheep, pigs, rats, mice, chicken), AMPK is widely expressed in different types of the ovarian cells (oocyte-cumulus complexes, granulosa cells, and theca cells) and in the corpus luteum [

186,

187,

189].

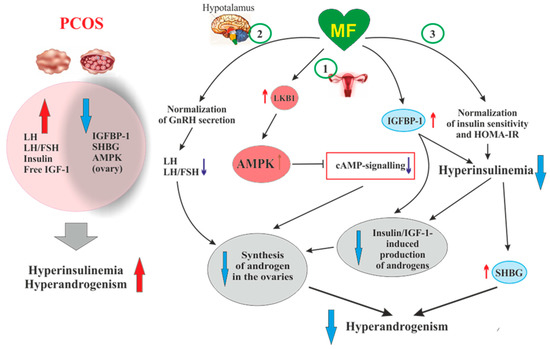

Figure 2. The pathways involved in the inhibitory effect of metformin on hyperandrogenism in PCOS. Hyperinsulinemia and HA are among the key pathogenetic factors in the development of PCOS, which is why, their attenuation by MF is the most important mechanism for improving effect of this drug on ovarian function in PCOS women. In PCOS, MF-induced increase in insulin sensitivity leads to a decrease in the HOMA-IR and a weakening of compensatory hyperinsulinemia. Another mechanism for lowering insulin levels may be an increase in the level of IGFBP-1, which specifically binds insulin and IGF-1. In PCOS, the expression of IGFBP-1 is generally reduced, and MF treatment may be one way to normalize it. A reduced hyperinsulinemia and an increase in IGFB-1 levels lead to a decrease in the stimulating effect of insulin and IGF-1 on the ovarian steroidogenesis and a weakening of HA. Hyperinsulinemia leads to a decrease in the production of SHBG, which provokes HA in PCOS. MF-induced reduction of hyperinsulinemia leads to the normalization of the SHBG levels, thereby preventing excess androgen levels in the blood. By improving the functionality of the hypothalamic signaling network responsible for the pulsatile secretion of GnRH, treatment with MF leads to the normalization of blood LH levels and the LH/FSH ratio, both of which are increased in PCOS. A decrease in blood LH levels results in a weakening of gonadotropin-induced androgen production by the ovaries. A direct regulatory effect of MF on ovarian steroidogenesis was also established. By inhibiting the mitochondrial ETC complex I, stimulating the LKB1 activity and, as a result, increasing the AMPK activity, MF reduces the synthesis of androstenedione in the ovarian cells and prevents HA. It can be assumed that the prevalence of some mechanisms of the inhibitory effect of MF on HA is due to the characteristic features of PCOS pathogenesis and the metabolic and hormonal status of the ovaries. Details and bibliographic references are presented in the

Section 2.4. Abbreviations: AMPK, AMP-activated protein kinase; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HA, hyperandrogenism; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; IGFBP-1, insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1; LH, luteinizing hormone; LKB1, liver kinase B1; SHBG, androgen and sex hormone-binding globulin.

There is a large body of experimental data that AMPK is essential for the regulation of folliculogenesis and meiotic activity, both control the maturation of oocytes [

186,

190,

191,

192,

193,

194], and that AMPK is involved in the regulation of steroidogenesis in ovarian granulosa cells [

187,

195]. Deletion of the AMPK α1-subunit in mouse oocytes leads to a 27% decrease in litter size, and after IVF, the number of embryos in these mutant mice decreases by 68% [

196]. In the ovaries of mutant mice, the levels of transmembrane connexin-37 and

N-cadherin, which mediate the intercellular communication and are involved in the formation of the oocyte-cumulus complexes, were significantly reduced. The activity level within cAMP-dependent cascade, which includes PKA and factor CREB, and the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) cascade are reduced, indicating weakening of cAMP- and MAPK-mediated signal transduction [

195,

196]. The components of these signaling pathways are involved in the junctional communication between the oocyte and the cumulus/granulosa cells. The MII oocytes in mice lacking the α1-AMPK have a significantly reduced intracellular ATP level and decreased levels of cytochrome

c and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α (PGC1α), which indicates the impaired mitochondrial biogenesis and the activation of apoptotic processes [

196].

In ovarian cells, through the activation of AMPK, MF inhibits the cAMP signaling pathways, decreases the expression and activity of the steroidogenic enzymes and the production of androstenedione, a precursor of testosterone (). When exposed to cultured human theca cells, both in the basal and forskolin-stimulated state, application of MF (50 and 200 μM) caused the AMPK stimulation and reduced androstenedione synthesis in dose-dependent manner. In theca cells stimulated by forskolin, a non-hormonal AC activator, MF suppressed the expression of

StAR and

Cyp171a genes encoding StAR protein, which carries out cholesterol transport into mitochondria (the first, rate-limiting stage of steroidogenesis), and cytochrome P450c17α, which catalyzes the synthesis of androstenedione [

184]. The inhibitory effect of MF on steroidogenesis in the rat and bovine granulosa cells was also due to AMPK activation, as indicated by an increase of Thr

172 phosphorylation of AMPK α-subunit, as well as an increase of Ser

79 phosphorylation and inhibition of the main target of AMPK, the enzyme acetyl-CoA-carboxylase [

186,

197]. The involvement of AMPK in the antiandrogenic action of MF is supported by the data on a similar effect of 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide ribonucleotide (AICAR), the pharmacological activator of AMPK [

186]. The MF-induced stimulation of AMPK in granulosa cells results in a decrease in the activity of MAPK cascade, primarily the kinases ERK1/2, and inhibition of phosphorylation of MAPK-activated protein kinase-1, also referred to as ribosomal s6 kinase (p90

RSK) [

186,

197,

198]. Therefore, through the AMPK-dependent mechanisms, MF not only reduces the excessive steroidogenic activity in ovarian cells, but also suppresses and/or modulates the cell growth and intracellular protein synthesis.

An important role of AMPK-dependent mechanisms in the antiandrogenic action of MF in PCOS is supported by the data on the relationship between the androgen production and the activity of LKB1 in the ovaries of mice with experimental HA [

199]. The LKB1 expression in the ovaries of hyperandrogenic mice is inhibited by high concentrations of androgens through activation of intracellular androgen receptors. In opposite, LKB1 activation leads to a decrease in the androgens production by theca cells, but increases the estrogen production by granulosa cells. Transgenic mice overexpressing LKB1 are characterized by the increased resistance to the development of HA [

199]. Mice with a functionally inactive ovarian gene

Lkb1 have significantly enlarged ovaries and activated entire pool of primordial follicles, but without further maturation and ovulation, which results in the premature ovarian failure and severely reduced fertility [

200]. The data indicates that MF-induced activation of LKB1/AMPK pathway in PCOS ovaries normalizes ovarian steroidogenesis and counteracts HA ().

Another, very important mechanism of antiandrogenic action of MF is largely due to an MF-induced increase in insulin sensitivity and consequent weakening of compensatory hyperinsulinemia, the main pathogenic factor in PCOS, also closely associated with HA [

201,

202,

203] ().

It is generally accepted that the stimulating effect of hyperinsulinemia on the production of androgens by ovarian cells is based on low affinity binding of insulin with IGF-1 receptors [

203,

204,

205]. In the 1990s, it was shown that insulin in vitro and in vivo activates the IGF-1 receptor in the ovaries, which leads to an increase in the synthesis and secretion of androgens. This is supported by the data on the increased secretion of androstenedione and the elevated basal and LH-stimulated production of testosterone in cultured ovarian theca and stroma cells incubated in the presence of insulin [

204,

206]. A decrease in insulin secretion induced by MF (500 mg three times daily) in obese PCOS women led to inhibition of cytochrome P450c17α activity in the ovaries, decreasing the basal levels of 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and the levels of this hormone stimulated by leuprolide, a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) analogue [

171].

Along with the activation of IGF-1 receptor, hyperinsulinemia reduces the production of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1) by ovarian granulosa cells [

204] (). This protein specifically binds IGF-1, decreasing the concentration of free IGF-1 and weakening its stimulating effect on the IGF-1 receptor and steroidogenesis in the ovarian theca and stromal cells. The result of insulin-induced decrease in IGFBP-1 level is overproduction of androgens and the impaired folliculogenesis and ovulatory cycle [

207]. It should be noted that IGF-1, like insulin, reduces the IGFBP-1 production in ovarian cells, while FSH stimulates the IGFBP-1 production, preventing IGF-1-induced stimulation of androgen production [

207]. The blood IGFBP-1 levels in PCOS women are significantly lower compare to than in healthy women, which may indicate suppression of IGFBP-1 production under the conditions of hyperinsulinemia [

201,

203]. At the same time, there is no strong correlation between the IGFBP-1 deficiency and the severity of hyperinsulinemia and IR, which suggests the presence of additional mechanisms mediating the inhibition of IGFBP-1 production in PCOS [

203]. There are no data for the MF effect on blood IGFBP-1 levels in PCOS, but there is evidence of its significant increase in MF-treated women with GDM [

208]. MF caused an increase in both phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated forms of IGFBP-1, thereby reducing the negative effect of IGFBP-1 deficiency on the course and outcomes of pregnancy [

208].

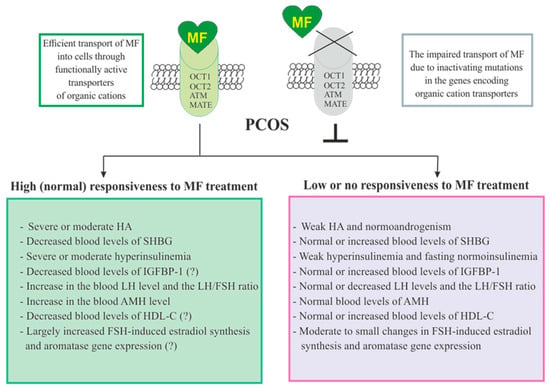

In PCOS, the blood levels of androgen and sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) are reduced, which leads to an increase in free testosterone level and free androgen index. As early as the 1990s, hyperinsulinemia was found to be an important factor for the suppression of SHBG production in PCOS [

171,

209,

210]. Overweight plays a key role in this process, as supported by observation that weight loss in obese PCOS women induced by a low-calorie diet leads to a restoration of SHBG levels, which may be due to a decrease in IR and insulin levels [

211]. MF administration increases the production of SHBG, by reducing body weight and hyperinsulinemia, and, thereby, reduces the signs of HA in PCOS women [

171,

212,

213] (). Blood SHBG levels are also increased in MF-treated obese women without clear signs of PCOS [

214]. The PCOS women with low SHBG levels are more sensitive to MF therapy, while the effectiveness of MF in patients with normal or high SHBG levels and, as a consequence, without signs of HA is significantly less noticeable. The PCOS women with an average SHBG level in the blood of 37.5 nmol/L respond well to MF treatment, while in PCOS women with an average SHBG level of 56.0 nmol/L, the response to MF was weak [

215]. Therefore, the assessment of the blood SHBG concentration is an important prognostic factor for predicting the effectiveness of MF therapy in PCOS. Thus, a MF-induced decrease in the level of insulin should lead to a weakening of the stimulating effect of insulin on the ovarian IGF-1 receptors, prevent their stimulation by an excess of free IGF-1, and reduce the blood level of free androgens by restoring the SHBG production.

Of great importance for normalization of the steroidogenic function in the ovaries can be MF-induced decrease in the blood LH level and the LH/FSH ratio, which are significantly increased in PCOS [

216,

217,

218,

219] (). An increase in the LH/FSH ratio due to abnormal gonadotropin pulsatility and hypersecretion of LH by the pituitary is a significant factor responsible for the deterioration of folliculogenesis and oogenesis in PCOS [

219,

220,

221,

222,

223,

224]. In most cases, gonadotropin imbalance is found in PCOS women with obesity, and level of increase in LH is correlated with the severity of obesity [

220]. The restoration of this ratio leads to normalization of the ovulatory cycle and triggers the development of the dominant follicle, improving the rate and outcomes of pregnancy [

222,

225]. Eight-week treatment of PCOS women with MF (1500 mg/daily) results in a 32% decrease in the blood LH levels and a 42% decrease in the LH/FSH ratio [

218]. There is reason to believe that, as in the case of SHBG, the sensitivity of PCOS women to MF therapy depends on the LH level and the LH/FSH ratio. The MF treatment of PCOS women with severely impaired gonadotropin secretion and significantly increased LH level is more effective than the same treatment of PCOS women without gonadotropin imbalance [

226].

It is suggested that the restoration of normal LH secretion by the pituitary gland may be due to MF-induced normalization of AMPK-dependent signaling in hypothalamic neurons secreting GnRH [

227] (). This is due to the ability of MF to cross the blood-brain barrier and reach the hypothalamus and the other brain regions [

228]. The secretion of GnRH is under the control of neuropeptides, such as kisspeptin, melanocortins, agouti-related peptide and neuropeptide Y, as well as γ-aminobutyric acid and the other biogenic amines [

229], and the neurons producing these neurohormones may also be pharmacological targets for MF. The restoration of functional interaction between GnRH-expressing neurons and the other components of the neuronal network responsible for hypothalamic control of the HPG axis can prevent PCOS-associated HA and provide a balance between steroid hormones, thereby normalizing the functionality of feedback loops in this axis. Our group and other authors have demonstrated the restoring effect of MF on leptin signaling pathways in the hypothalamus of animals with metabolic disorders and IR [

230,

231,

232,

233], and the improvement of hypothalamic leptin signaling can also make a significant contribution to the restoration the reproductive functions in PCOS. It should be noted that MF, both at the periphery and in the CNS, acts on the signaling and effector systems synergistically with leptin. It is generally accepted that leptin is the most important regulator of the female and male reproductive systems, which stimulates the activity of hypothalamic GnRH-expressing neurons, and affects the other links of the HPG axis [

234,

235].

2.4.3. Effects of Metformin on FSH-Activated Signaling in the PCOS Ovaries

Another mechanism of the MF restoring effect on ovarian function in PCOS is the inhibition of expression of the

Cyp19a1 gene encoding aromatase. Reduced levels of aromatase result in a decrease in estrogen response to FSH, insulin and IGF-1 in the ovaries [

185,

244,

245,

246]. A large number of PCOS patients have increased sensitivity of granulosa cells to stimulation with FSH, insulin, or IGF-1. This is due to the fact that in granulosa cells of PCOS women, the expression of the FSH and IGF-1 receptors and the IRS1 and IRS2 proteins are significantly increased [

247,

248,

249,

250,

251,

252]. In addition, the expression of PTEN, a negative regulator of signaling pathway involving insulin/IGF-1 receptors, IRS proteins, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K) and Akt-kinase, is reduced, which leads to hyperactivation of Akt-kinase by insulin and IGF-1 [

251]. In the PCOS ovaries, the important mechanism of suppression of PTEN expression and hyperactivation of the insulin and IGF-1 signaling pathways is an increase in the expression of two microRNAs of miR-200 family, miR-200b and miR-200c, which negatively affect the expression of the

PTEN gene [

252]. In addition, a decrease in the expression of miR-99a, a negative regulator of IGF-1 receptor expression, leads to an increase in the sensitivity of granulosa cells to IGF-1 [

218]. An increase in the expression and activity of the receptor and postreceptor components of the FSH-, insulin- and IGF-1-regulated signaling systems in PCOS results in the accelerated growth and proliferation of the ovarian cells, primarily granulosa cells, in the response to the stimulating effect of these hormones. Moreover, this potentiates already pre-existing increased ovarian reactivity and premature luteinization [

207,

253,

254].

MF reduces the expression of FSH receptors thereby weakening the stimulating effects of FSH on steroidogenesis and proliferation of granulosa cells, increased in PCOS, which leads to the normalization of folliculogenesis and ovulation. Under the conditions of ovarian dysfunctions in PCOS, MF treatment postpones the triggering of processes that ensure the normal growth of antral follicles, thus providing more appropriate window of time required for their differentiation and development (on average about three months) [

245]. By reducing the ovarian sensitivity to FSH, MF prevents the OHSS, the most common complication of gonadotropin-stimulated induction of ovulation [

135,

136,

138,

255,

256].

The inhibitory and modulating effects of MF on the effector components of gonadotropin-stimulated cascades in ovarian cells can be realized through both AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent pathways, including the MAPK cascade [

244,

245]. Through AMPK-independent pathways, MF reduces FSH-induced increases in aromatase activity and estradiol synthesis in granulosa cells, and this effect is not reproduced when using AICAR [

245]. The inhibitory effect of MF on the expression and activity of aromatase can be elicited through at least three well understood mechanisms.

The first mechanism is MF-induced inhibition of the expression of FSH receptor in granulosa cells, which reduces the stimulatory effect of FSH on the intracellular signaling pathways through which FSH controls the expression of aromatase and steroidogenic enzymes [

245]. As noted above, in granulosa cells of women with PCOS, the expression of the

Fshr gene is often significantly increased, which causes the elevated responsiveness of the ovaries to FSH [

247,

248,

249]. The polymorphisms in the

Fshr gene can have a significant role in modulating the responsiveness to FSH in both, positive and negative way, although in PCOS the data on the interrelation between

Fshr isoforms and the activity of FSH receptor are contradictory [

257]. At the same time, there is evidence that some polymorphisms can lead to an increase in the sensitivity of FSH receptor to gonadotropin [

258,

259]. The second mechanism of the inhibitory effect of MF on aromatase activity is due to a decrease in FSH-induced phosphorylation of the transcription factor CREB, which positively regulates the expression of the aromatase gene, as well as the

Star,

CYP11a1 and

HSD3b genes encoding the cholesterol-transporting protein StAR, cytochrome P450scc (CYP11A1), which catalyzes the synthesis of pregnenolone, and 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β-HSD), which converts pregnenolone to progesterone [

245]. The third mechanism involves inhibition of FSH-induced dephosphorylation of the CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 2 (CRTC2) and its translocation into the nucleus, where CRTC2 is involved in the assembly of CREB containing activating transcriptional complex [

245]. Thus, MF inhibits the formation of the CREB-CBP-CRTC2 activation complex, which is capable of binding to the CRE regulatory elements in the promoter of the genes encoding aromatase and some steroidogenic proteins, and prevents their overexpression by FSH.

The FSH- and insulin/IGF-1-activated signaling pathways in ovarian cells are closely interrelated due to cross-talk between them, including their interaction through the PKA/PI 3-K/Akt pathway [

260,

261]. The functional activity of Akt kinase is increased as a result of these pathways activation in the conditions of overstimulation of FSH receptor and FSH-mediated activation of IRS1 protein. This leads to an increase in the survival of ovarian cells, suppresses atresia of the follicles and impairs maturation of the dominant follicle.

The FSH-dependent pathways are also regulated by the members of the transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) family, including activins, inhibins, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH). Activins increase the FSH receptor expression and enhance the stimulatory effects of FSH on ovarian steroidogenesis [

262,

263]. In contrast, AMH and inhibins suppress the stimulatory effects of FSH on folliculogenesis [

249,

262,

264,

265]. The regulatory effects of the protein members of the TGF-β-family on the FSH-dependent signaling pathways can be realized through both Akt- and cAMP-dependent mechanisms [

266,

267,

268,

269], but the effect of MF on the TGF-β-mediated regulation of the FSH signaling pathways in granulosa cells remains poorly understood.

2.4.4. The Effect of Metformin on the Production of Anti-Müllerian Hormone in PCOS

In PCOS, one of the targets of MF therapy is AMH, a dimeric glycoprotein that is produced by the granulosa cells of the primary, preantral and small antral follicles [

270,

271]. AMH concentration in the blood of women positively correlates with the follicular reserve and, as a result, in PCOS, the blood levels of AMH are usually increased by two or more fold [

251,

271,

272,

273,

274]. Excess levels of AMH lead to an impaired folliculogenesis, preventing the recruitment of primordial follicles into the pool of growing follicles and reducing the responsiveness of growing follicles to FSH [

249,

275,

276,

277]. The increased levels of AMH may be due to HA and hyperinsulinemia, which are characteristic features of PCOS and are closely interrelated [

249,

273,

278,

279,

280], as well as to an increase in blood LH levels or the sensitivity of granulosa cells to LH, typical for PCOS patients [

280,

281,

282,

283]. In in vitro experiments using lutein granulosa cells obtained from oligo/anovulatory PCOS women, the LH increases the AMH production, while the expression of type II AMH receptors in these cells does not change significantly. In the case of lutein granulosa cells obtained from healthy women and normo-ovulatory PCOS women, the stimulating effect of LH on AMH production is almost completely inhibited, but the inhibiting effect of LH on the expression of type II AMH receptors is preserved. This effect was reproduced with the use of cAMP analogs, which indicates the participation of cAMP-dependent mechanisms in it [

281]. All this indicates that PCOS women with an impaired ovulatory cycle have an increase in both the LH-induced AMH production and the responsiveness of lutein granulosa cells to this factor.

By lowering insulin and androgen levels and normalizing gonadotropin levels, MF attenuates ovarian AMH secretion, which leads to a decrease of its inhibitory effect on folliculogenesis and a weakening of the signs of PCOS [

270,

271,

284,

285,

286,

287,

288]. Eight-week treatment of PCOS women with MF (1500 mg/day) reduced the blood AMH levels from 10 ± 3.75 to 7.8 ± 3.7 ng/mL [

271]. Six-month treatment with MF at the same dose led to a decrease in AMH, ovarian volume and antral follicle number in PCOS women [

270]. The treatment of PCOS women with MF at the doses of 850 mg/day (first week), 850 mg/12 h (second week) and 850 mg/8 h (next six weeks), along with the restoration of ovulation and the normalization of LH and testosterone levels, caused a decrease in the blood AMH levels, from 8.99 ± 0.99 to 6.28 ± 0.46 ng/mL [

286]. The combined therapy with MF and resveratrol of rats with DHEA-induced PCOS reduced ovarian size, improved ovarian follicular cell architecture, and decreased AMH production [

217]. It is assumed that in PCOS, a decrease in the blood AMH level to control values can be considered as one of the prognostic factors of the effectiveness of MF therapy [

285,

286,

289].

However, there are clinical studies that showed a weak suppressive effect of MF therapy on AMH production in PCOS [

290], or the absence of this effect [

291,

292]. This may be due to differences in the MF doses, the duration of MF treatment, and the peculiarities of the hormonal status in PCOS patients. MF treatment of PCOS women for 8 months led to a decrease in the blood AMH level, while four-month MF therapy had a little effect on AMH concentration, although it significantly reduced the blood level of androstenedione and normalized the regularity of the menstrual cycle [

284]. It is possible, that normalization of the AMH level at the first stage requires normalization of androgens, insulin and gonadotropins levels, which in turn affects the expression and secretion of AMH. On the other hand, Iraqi scientists showed that the treatment of PCOS women with MF (500 mg three times daily) for three or six months significantly reduced the blood AMH levels, but in the case of six-month therapy, the MF effect became less pronounced [

289]. There is reason to believe that the severity of obesity, as well as the degree of an increase in AMH levels, can have a significant effect on the inhibitory effect of MF on ovarian AMH production. The most pronounced inhibitory effect of MF on AMH production was demonstrated in PCOS women with a higher body mass index, as well as with a higher level of AMH [

285].

Based on the above results, as well as on the available data on the molecular mechanisms mediating the regulation of AMH production by granulosa cells [

249,

293], it can be assumed that the main mechanism for the improving effect of MF on AMH levels in PCOS is the weakening of HA. Under normal conditions, the androgens produced by theca cells induce a decrease in AMH levels, which leads to inhibition of the antral follicle development and precedes ovulation. With prolonged exposure to high concentrations of androgens, which are comparable to those in PCOS, the response of granulosa cells to androgens is impaired, resulting in the absence of an androgen-induced fall in AMH levels and dysregulation of follicular development [

293]. When PCOS patients are treated with MF, their androgen levels are normalized, and hyperinsulinemia, which is usually associated with HA, is reduced, which leads to the restoration of the granulosa cell response to androgens. Accordingly, the low efficacy of MF in reducing AMH levels and restoring follicular maturation in patients with PCOS may be due to initially mild HA and IR. It is impossible to exclude the direct effects of MF on the production of AMH by follicular cells, including through AMPK-dependent mechanisms, as well as through weakening the stress of the endoplasmic reticulum, stimulated by high concentrations of androgens [

237]. However, this issue has not yet been studied.

There are only two clinical studies on the MF effect on the levels of other TGF-β family factors. One of them showed the normalization of the TGF-β level in the blood of PCOS women with MF and cyproterone acetate/ethinyloestradiol treatment [

294]. The other authors demonstrated that a long-term therapy with MF (more than three months) led to a significant decrease in the blood level of inhibin-B in PCOS patients [

289].