Пандемия коронавирусной инфекции 2019 года (COVID-19), вызванная высококонтагиозным вирусом SARS-CoV-2, спровоцировала глобальный кризис в области здравоохранения и экономики. Контроль над распространением болезни требует эффективной и масштабируемой лабораторной стратегии тестирования населения на основе нескольких платформ для обеспечения быстрой и точной диагностики.

- COVID-19

- SARS-CoV-2

- reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Примечание: следующее содержание является выдержкой из вашей статьи. Запись будет доступна онлайн только после того, как автор проверит и отправит ее.

1. Введение

В конце 2019 года в Китае были зафиксированы первые случаи новой вирусной инфекции, получившей название COVID-19. Возбудителем заболевания является ранее неизвестный и очень заразный тип коронавируса SARS-CoV-2 [1,2]. Последующее глобальное распространение инфекции стало катастрофической пандемией и спровоцировало серьезный кризис в мировой системе здравоохранения и экономике [1]. Этот вирус легко передается между людьми воздушно-капельным путем и поэтому быстро распространяется в густонаселенных районах. По данным Европейского центра профилактики и контроля заболеваний, количество случаев COVID-19 во всем мире в ноябре 2020 года составило более 62 миллионов, из которых более 1,4 миллиона умерли [2–4].

Сходство клинических проявлений инфекции с симптомами других ОРВИ, вероятность бессимптомной формы заболевания, а также относительно высокая контагиозность затрудняют эпидемиологический мониторинг распространения вируса. В связи с этим особую актуальность приобрели платформы, созданные для эффективной диагностики COVID-19, поскольку они обеспечивают своевременное выявление и лечение заболевших пациентов и мониторинг эпидемиологической ситуации, используя опыт борьбы с другими недавними вирусными эпидемиями [1,3, 4].

Появление в 21 веке трех новых типов патогенных для человека коронавирусов вызывает серьезные опасения. Это РНК-содержащие члены семейства Coronaviridae, включая MERS-CoV, ранее описанный возбудитель респираторного синдрома Ближнего Востока (MERS, Jordan, 2012), и SARS-CoV-1, возбудитель острого респираторного синдрома. (SARS, Китай, 2002 г.) [5–7]. Кроме того, некоторые штаммы α- и β-коронавирусов (HCoV-NL63, HCoV-OC43, HCoV-229E и HCoV-HKU1) также могут вызывать респираторные заболевания, кишечные или неврологические расстройства у людей [8].

A genome-wide sequencing and phylogenetic analysis showed that the causative agent of COVID-19 is a β-coronavirus of the same subgenus as the SARS-CoV that has a rounded shape with a diameter of 60 to 140 nm [5,9]. To successfully control a pandemic, in addition to studying the viral agent, it is necessary to identify the main mechanisms of infection and determine the key strategies for diagnosing the infection.

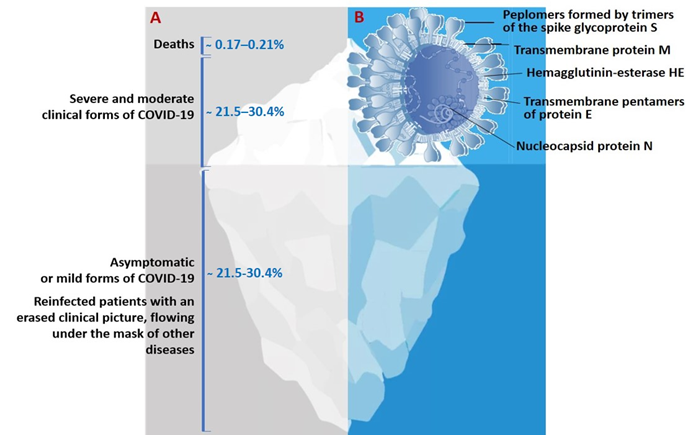

The genome of SARS-CoV-2 is a single-stranded positive-sense RNA of 29,903 nucleotides [10,11]. This genome encodes as many as 27 structural and non-structural proteins that provide transcription and replication of the virus (genes ORFlab and ORFla), as well as its pathogenic effects. The viral proteome includes polyproteins, structural and non-structural proteins. Some of the structural proteins such as, primarily, the spike glycoprotein (S) exposed on the phospholipid membrane, as well as the envelope protein (E), membrane protein (M), and nucleocapsid (N), are of particular biotechnological, pharmacological, and biomedical interest [6,7,9–12] (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. (A)The actual picture of the spread of COVID-19, resembling an iceberg and (B) some of the SARS-CoV-2 structural proteins of biotechnological and pharmacological interest.

The results of a molecular phylogenetic analysis showed that the genomes of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV, are related with an approximately 80% similarity. In particular, they share the largest of the structural proteins, glycoprotein S, which protrudes from the surface of mature virions. The S-protein plays key roles in virus attachment, fusion, and entry into human cells. For this purpose, the virus uses receptor-binding domain (RBD), which mediates binding to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) [11,13–15]. The highly immunogenic receptor-binding domain (RBD) of this protein is the main target for the neutralizing activity of antibodies and serves as a basis for the development of vaccines [16–18].

2. Laboratory Testing as A Basis for the Diagnosis, Treatment, and Monitoring of COVID-19

One of the most important issues in the strategy to control the new infection has been the necessity of mass laboratory-based screening of populations exposed to high risk of infection. The timely and high-quality laboratory-based diagnostics of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 has become the top priority in eliminating the pandemic and taking quarantine measures [1,4,5,16]. Under these conditions, the creation of fast, effective, and inexpensive diagnostic tools is a necessary part of the fight against the new infection. When diagnosing COVID-19, the major challenge that the healthcare system faces is to identify the role and place of various diagnostic platforms for screening, diagnosing, and monitoring new coronavirus infections [8,9,19].

The results of the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing have become a basis for the development of vaccines and test systems to provide diagnosis and epidemic monitoring of the infection [19]. However, with lack of experience in eliminating the COVID-19 pandemic, the healthcare system now faces new issues and problems such as timeliness, frequency, and choice of testing tools, as well as identification of the place and role of their results in decision-making. These questions can be answered through solving the issues of availability of certain types of laboratory tests, timeliness of testing and their informativeness, and also the clinical, epidemiological and economic feasibility of their use in the rapidly changing and unprecedented pattern of the spread of the pandemic in recent history [15,20–22].

To date, there are substantial differences in the choice of optimal diagnostic tools and effective methods for testing patients with COVID-19, their contacts, asymptomatic vectors of the virus, medical specialists and other representatives of emergency medical services [1,2,19,22]. After nearly a year of fighting COVID-19, healthcare efforts are still measured in terms of number of tests performed [19,22].

The dynamics and sensitivity of laboratory tests for this category of patient remains unstudied, and they can become a source of infection for others [23]. This suggests that laboratory-based diagnostic strategies aimed at patients with symptoms are not sufficient to prevent the spread of the virus [20–22].

Negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests and the detection of presence of specific antibodies are considered the criteria signifying a recovered patient, without considering the consequences on their health and quality of life. Nevertheless, levels of antibodies in those who have recovered are not further investigated, and the intensity of immunity and the possibility of re-infection by COVID-19 also remain unstudied [17,21]. This is probably due to the lack of understanding of the immune signaling pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2, as well as the general immunopathology of this infection [2,3,22].

Consequently, a rapid, complete, and most accurate assessment of the spread of the virus requires laboratory-based tests for total screening of the population, which will allow rapid identification and isolation of infected patients. In addition, there is a necessity for a long-term strategy for preventing recurrent outbreaks of infection, which would imply repeated and regular mass testing of the immune response in the population to determine the effectiveness of vaccination [6,9,21,24].

The situation regarding the diagnostics of COVID-19 is further complicated by the lack of awareness in society, the mass media, among medical officials and some biomedical specialists concerning the differences between the existing types of diagnostic tests for this infection. Therefore, it is not surprising that neither a unified methodology with clear goals and objectives, nor an agreed interpretation of the results obtained yet exists [2,3,25].

Obviously, one of the major issues in the development of a testing strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic is associated with the existing types of diagnostic tool and their fundamental difference, clinical practicability, and uselessness for certain categories of patients at different stages of the disease. Other widely discussed issues are timing of testing, frequency, and correct interpretation of results obtained [2,3,5,7].

3. Laboratory-Based Tests to Diagnose COVID-19

Data obtained from routine laboratory examinations are non-specific (leukopenia, lymphopenia, mild thrombocytopenia, increased levels of acute phase proteins, decreased partial pressure of oxygen in the blood, and, in severe cases, identification of markers of cytokine storm in the form of increased levels of cytokines IL2, IL4, IL6, IL7, IL10, and TNF-α). These tests are helpful in treatment of patients diagnosed as COVID-19 positive [12,14,17,18].

All currently existing types of special laboratory tests for diagnosing COVID-19 can be divided into two categories: those that directly detect the virus (its genome or antigens) and those that detect the human immune response to its presence (antibodies IgM, IgA, and IgG).

Laboratory-based tests for COVID-19 are used for a variety of purposes. A diagnostic examination is carried out for patients with clinical symptoms (complaints) in order to confirm the diagnosis. A screening study is carried out for people who feel healthy in order to identify disease among them (including the asymptomatic form of infection). At last, monitoring is carried out for patients undergoing treatment in order to assess the effectiveness or dynamics of the latter [19,21,24].

With the lack of specific symptoms and lack of proven effectiveness of etiotropic treatment and vaccination methods, the results of special laboratory diagnostics are the only source of data to confirm the presence and provide monitoring of the progress of COVID-19 [3,23,24,26].

The main analytical characteristics of laboratory-based tests are their sensitivity (which is evaluated as the probability of positive result in a patient with the disease) and specificity (negative test results in a healthy person). In addition, the effectiveness of tests is evaluated by their predictive value: the post-test probability of the disease in persons with a positive test result and its absence in persons with a negative test result.

Most test system manufacturers report high analytical performance (90%–100%) in cases in which their test systems are used under ideal conditions. However, in an actual situation, the diagnostic efficiency of a test depends on a number of factors (such as the clinical form of COVID-19, the duration of the disease, the quality of collection and the type of biomaterial, the conditions of its storage, transportation, etc.).

In an ideal (hypothetical) case, when using a test that detects SARS-CoV-2 and has 100% sensitivity and specificity, it would be possible to survey the entire world’s population. Depending on the results obtained, all infected patients can be sorted out and divided into the following categories: asymptomatic carriage and, depending on the clinical manifestation, mild, moderate and severe COVID-19. Accordingly, all patients with positive tests, depending on the clinical signs, are isolated either for quarantine, or home treatment, or treatment at a medical unit.

Alternatively, in another hypothetical case, the entire population is screened for the presence of IgG antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using another test that has a 100% sensitivity and specificity to identify patients who were previously infected but had the asymptomatic form or were immune to the virus. These categories of the population, with their antibody level regularly monitored, could be recruited as volunteer to provide social or medical assistance to diseased people.

The actual pattern of distribution of COVID-19 resembles an iceberg, where the categories of seriously ill and hospitalized patients are in the smaller, above-water, part, and those who die from infection are at the very top (Figure 1). The largest proportion of the underwater part of the iceberg is represented by patients who have had an infection in an asymptomatic form of the disease which, depending on gender and age, account for more than 78%, or the mild form, without specific clinical manifestation, or with symptoms of acute respiratory or other flu-like infections [4,7,19,22,27] (Figure 1A). In this case, asymptomatic patients bear the same viral load for the same period of time as those with the pronounced form of infection and are considered as the main source of infection spread [3,4,7,19,22].

Рассмотренные выше случаи, будучи все гипотетическими, помогают определить положение и оценить диагностическую ценность доступных тестов, а также практическую возможность их использования, особенно при отсутствии необходимых терапевтических агентов или вакцин.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jpm11010042