Diabetes and its vascular complications affect an increasing number of people. This disease of epidemic proportion nowadays involves abnormalities of large and small blood vessels, all commencing with alterations of the endothelial cell (EC) functions.

- diabetes

- hyperglycemia

- glycated lipoproteins

- endothelial cell dysfunction

- atherosclerosis

- molecular mechanisms

1. Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes mellitus (DM) is rapidly increasing worldwide[1]. The decreased quality of life of diabetic patients and the social and economic burden of this disease emphasize the need to establish the causative mechanisms of DM that will finally allow the identification of new therapies to cure diabetes and its associated vascular complications. Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the clinical manifestations of atherosclerosis, which represents one of the main vascular threats of diabetes. Published data show that the risk of acute cardiovascular events (such as stroke or myocardial infarction) is seven to ten times higher in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic subjects[2]. In addition, microvascular afflictions, including retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy and limb ischemia, occur at a very high rate in diabetic patients compared to non-diabetic individuals[2].

The primary cause of the pathophysiologic alterations of the diabetic patient’s vasculature is the exposure to high levels of blood glucose. It is well known that high glucose (HG) can induce vascular complications in diabetic patients by affecting the normal function of the vessel wall’s cells. Unfortunately, large-scale clinical studies have shown that despite good glycemic control, the vascular complications persist and even evolve[3][4]. This phenomenon is known as the “metabolic memory” of the cells[5]. The first cells of the vessel wall exposed to plasma HG are the endothelial cells (EC). Constant plasma hyperglycemia or intermittent HG due to poor glycemic control induces EC dysfunction (ECD)[6][7][8]. ECD is considered a critical step in the initiation and evolution of atherosclerosis[9]. It favors an increased trans-endothelial transport of plasma proteins and lipoproteins (Lp), stimulates the adhesion and sub-endothelial transmigration of blood monocytes, supports the migration and proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (SMC) from the media to the intima and impedes the fibrinolytic processes, finally increasing the risk of cardiovascular events in diabetic patients[10]. Prolonged plasma HG induces also the formation of advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which by non-enzymatic attachment to proteins compromise their proper functioning. The interaction between the receptor for AGE (RAGE) and AGE proteins activates numerous signaling pathways and represents a powerful determinant of ECD[11]. Glycated lipoproteins (gLp), which are formed in excess in the plasma of diabetic patients, are ligands for RAGE and contribute substantially to ECD.

2. Endothelial Cell Dysfunction in Diabetes

ECs are instrumental for maintaining the homeostasis of the vascular system due to their multiple functions. It is known that ECs participate in the regulation of the vascular tone by secreting different vasodilators (such as nitric oxide, prostacyclin) and vasoconstrictors (endothelin, thromboxanes). They act as a selective barrier to control the exchange of macromolecules between the blood and tissues, control the extravasation and the traffic of pro-inflammatory leucocytes by regulating the expression of the cell adhesion molecules and cytokines and keep the balance between the pro-thrombotic and pro-fibrinolytic factors[12][13].

In diabetes, the primary metabolic modification is the chronically elevated blood glucose. ECs are the first cells of the vascular wall that interact with the blood-increased glycemia and suffer structural and functional alterations[14][12]. The structural modifications of EC in diabetes start with the switch to a secretory phenotype, as demonstrated by the overdevelopment of the rough endoplasmic reticulum (RER) and Golgi complexes, the enrichment of the intermediary filaments and Weibel–Palade bodies, the enlargement of the inter-endothelial junctions, and the increase in the number of plasmalemmal vesicles favoring the formation of transendothelial channels[15][16]. These modifications determine the formation of a hyperplasic basal lamina and the increase in EC permeability, favoring the subendothelial accumulation of native and modified LDLs, which contribute to atheroma formation[14].

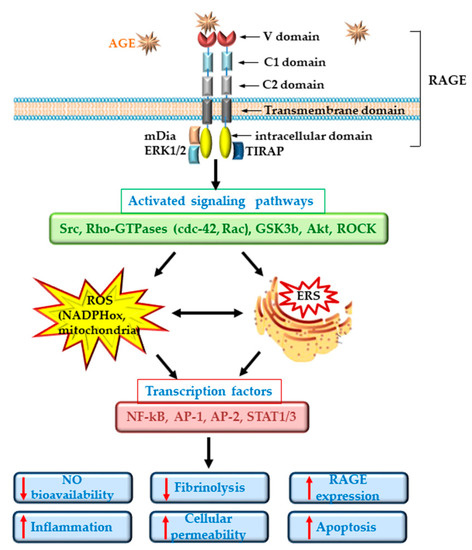

ECD in diabetes is well documented and is regarded as an important player in the pathogenesis of CVD[17]. Dysfunctional ECs suffer a shift to a vasoconstrictor, pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory phenotypes. RAGE plays an important role in the development of the vascular complications associated with diabetes. It was demonstrated that deletion of RAGE in different animal models determines a significant attenuation of the atherosclerotic process[18][19]. The specific deletion of the cytoplasmic domain of RAGE of EC in transgenic mice was associated with a decrease in the inflammatory stress, revealing a prominent role for RAGE in ECD[18]. Studies in cultured EC have demonstrated that the interaction of different AGEs with RAGE determines the development of oxidative stress by activation of NADPH oxidase or induction of mitochondrial dysfunction[11][20][21] and lowers the bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO)[12]. In addition, series of intracellular phosphorylation reactions leading to the activation of MAPK (such as ERK1/2, p38), the enhancing of Jak/Stat signaling pathway and the activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) are induced[22]. These effects result in the stimulation of the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including interleukin-6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) and the overexpression of adhesion molecules, such as vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) or intracellular cell adhesion molecule (ICAM-1), exacerbating the atherosclerotic process in diabetes[23][24][25]. Of great importance, it was demonstrated that AGEs increase the endothelial hyper-permeability by dissociating the adherens junctions through RAGE-mDia1 binding[26]. Interestingly, active NF-kB is also involved in the transcription of RAGE and of some of its ligands (such as HMGB1). Thus, the primary activation of RAGE unfortunately generates a positive feedback loop of self-sustained activation cycle, through NF-kB, amplifying the deleterious effects of AGE/RAGE interactions[27] (Figure 1).

In diabetic patients, the alteration of EC function was measured as: decreased forearm blood flow[28][29], increased levels of soluble adhesion molecules such as E-selectin, soluble VCAM-1 or soluble ICAM-1[30][31], elevated plasma levels of von Willebrand factor (vWF) and PAI-1[29][32][33]. More than being just a consequence of diabetes, ECD plays an important role in the development of microvascular (nephropathy, retinopathy, neuropathy) and macrovascular (ischemic heart disease, stroke, peripheral vascular disease) complications of diabetes[17].

3. Conclusion

Reversal of endothelial dysfunction is an open and exciting field of investigation, of fundamental relevance for many diseases, and in particular for diabetes and atherosclerosis. The progress of biotechnology field will permit the use of targeted nanosystems such as nanoliposomes or nanoemulsions, or the specific regulation of different proteins based on the new CRISP/Cas9 technology to reverse endothelial dysfunction in diabetes, as well as other pathologies. In the future, these and other promising therapies focused on EC-based translational approaches will provide powerful tools to increase the life quality of diabetic patients.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines9010018

References

- Oguntibeju, O.O. Type 2 diabetes mellitus, oxidative stress and inflammation: examining the links. International journal of physiology, pathophysiology and pharmacology 2019, 11, 45-63

- Gregg, E.W.; Williams, D.E.; Geiss, L. Changes in diabetes-related complications in the United States. The New England journal of medicine 2014, 371, 286-287, doi:10.1056/NEJMc1406009.

- Nathan, D.M.; Cleary, P.A.; Backlund, J.Y.; Genuth, S.M.; Lachin, J.M.; Orchard, T.J.; Raskin, P.; Zinman, B.; Diabetes, C.; Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes, I., et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. The New England journal of medicine 2005, 353, 2643-2653, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052187.

- Holman, R.R.; Paul, S.K.; Bethel, M.A.; Matthews, D.R.; Neil, H.A. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. The New England journal of medicine 2008, 359, 1577-1589, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0806470.

- Ceriello, A. The emerging challenge in diabetes: the "metabolic memory". Vascular pharmacology 2012, 57, 133-138, doi:10.1016/j.vph.2012.05.005.

- An, H.; Wei, R.; Ke, J.; Yang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, G.; Hong, T. Metformin attenuates fluctuating glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction through enhancing GTPCH1-mediated eNOS recoupling and inhibiting NADPH oxidase. Journal of diabetes and its complications 2016, 30, 1017-1024, doi:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2016.04.018.

- Liu, T.; Gong, J.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, S. Periodic vs constant high glucose in inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Inflammation research : official journal of the European Histamine Research Society ... [et al.] 2013, 62, 697-701, doi:10.1007/s00011-013-0623-2.

- Liu, T.S.; Pei, Y.H.; Peng, Y.P.; Chen, J.; Jiang, S.S.; Gong, J.B. Oscillating high glucose enhances oxidative stress and apoptosis in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Journal of endocrinological investigation 2014, 37, 645-651, doi:10.1007/s40618-014-0086-5.

- Widlansky, M.E.; Hill, R.B. Mitochondrial regulation of diabetic vascular disease: an emerging opportunity. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine 2018, 202, 83-98, doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2018.07.015.

- Coco, C.; Sgarra, L.; Potenza, M.A.; Nacci, C.; Pasculli, B.; Barbano, R.; Parrella, P.; Montagnani, M. Can Epigenetics of Endothelial Dysfunction Represent the Key to Precision Medicine in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, doi:10.3390/ijms20122949.

- Fishman, S.L.; Sonmez, H.; Basman, C.; Singh, V.; Poretsky, L. The role of advanced glycation end-products in the development of coronary artery disease in patients with and without diabetes mellitus: a review. Molecular medicine 2018, 24, 59, doi:10.1186/s10020-018-0060-3.

- Meza, C.A.; La Favor, J.D.; Kim, D.H.; Hickner, R.C. Endothelial Dysfunction: Is There a Hyperglycemia-Induced Imbalance of NOX and NOS? International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, doi:10.3390/ijms20153775.

- Yau, J.W.; Teoh, H.; Verma, S. Endothelial cell control of thrombosis. BMC cardiovascular disorders 2015, 15, 130, doi:10.1186/s12872-015-0124-z.

- Simionescu, M.; Popov, D.; Sima, A. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. In Vascular involvement in diabetes – clinical, experimental and beyond, Cheta, D.M., Ed. Romanian Academy Publishing House and Karger: 2005; pp. 15-34.

- Mompeo, B.; Popov, D.; Sima, A.; Constantinescu, E.; Simionescu, M. Diabetes-induced structural changes of venous and arterial endothelium and smooth muscle cells. Journal of submicroscopic cytology and pathology 1998, 30, 475-484.

- Suganya, N.; Bhakkiyalakshmi, E.; Sarada, D.V.; Ramkumar, K.M. Reversibility of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes: role of polyphenols. The British journal of nutrition 2016, 116, 223-246, doi:10.1017/S0007114516001884.

- Shi, Y.; Vanhoutte, P.M. Macro- and microvascular endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Journal of diabetes 2017, 9, 434-449, doi:10.1111/1753-0407.12521.

- Harja, E.; Bu, D.X.; Hudson, B.I.; Chang, J.S.; Shen, X.; Hallam, K.; Kalea, A.Z.; Lu, Y.; Rosario, R.H.; Oruganti, S., et al. Vascular and inflammatory stresses mediate atherosclerosis via RAGE and its ligands in apoE-/- mice. The Journal of clinical investigation 2008, 118, 183-194, doi:10.1172/JCI32703.

- Sun, L.; Ishida, T.; Yasuda, T.; Kojima, Y.; Honjo, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Ishibashi, S.; Hirata, K.; Hayashi, Y. RAGE mediates oxidized LDL-induced pro-inflammatory effects and atherosclerosis in non-diabetic LDL receptor-deficient mice. Cardiovascular research 2009, 82, 371-381, doi:10.1093/cvr/cvp036.

- Dobi, A.; Bravo, S.B.; Veeren, B.; Paradela-Dobarro, B.; Alvarez, E.; Meilhac, O.; Viranaicken, W.; Baret, P.; Devin, A.; Rondeau, P. Advanced glycation end-products disrupt human endothelial cells redox homeostasis: new insights into reactive oxygen species production. Free radical research 2019, 53, 150-169, doi:10.1080/10715762.2018.1529866.

- Wang, C.C.; Lee, A.S.; Liu, S.H.; Chang, K.C.; Shen, M.Y.; Chang, C.T. Spironolactone ameliorates endothelial dysfunction through inhibition of the AGE/RAGE axis in a chronic renal failure rat model. BMC nephrology 2019, 20, 351, doi:10.1186/s12882-019-1534-4.

- Ott, C.; Jacobs, K.; Haucke, E.; Navarrete Santos, A.; Grune, T.; Simm, A. Role of advanced glycation end products in cellular signaling. Redox biology 2014, 2, 411-429, doi:10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.016.

- Schmidt, A.M.; Yan, S.D.; Wautier, J.L.; Stern, D. Activation of receptor for advanced glycation end products: a mechanism for chronic vascular dysfunction in diabetic vasculopathy and atherosclerosis. Circulation research 1999, 84, 489-497, doi:10.1161/01.res.84.5.489.

- Zhao, R.; Ren, S.; Moghadasain, M.H.; Rempel, J.D.; Shen, G.X. Involvement of fibrinolytic regulators in adhesion of monocytes to vascular endothelial cells induced by glycated LDL and to aorta from diabetic mice. Journal of leukocyte biology 2014, 95, 941-949, doi:10.1189/jlb.0513262.

- Toma, L.; Sanda, G.M.; Deleanu, M.; Stancu, C.S.; Sima, A.V. Glycated LDL increase VCAM-1 expression and secretion in endothelial cells and promote monocyte adhesion through mechanisms involving endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2016, 417, 169-179, doi:10.1007/s11010-016-2724-z.

- Zhou, X.; Weng, J.; Xu, J.; Xu, Q.; Wang, W.; Zhang, W.; Huang, Q.; Guo, X. Mdia1 is Crucial for Advanced Glycation End Product-Induced Endothelial Hyperpermeability. Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 2018, 45, 1717-1730, doi:10.1159/000487780.

- Li, J.; Schmidt, A.M. Characterization and functional analysis of the promoter of RAGE, the receptor for advanced glycation end products. The Journal of biological chemistry 1997, 272, 16498-16506, doi:10.1074/jbc.272.26.16498.

- Caballero, A.E.; Arora, S.; Saouaf, R.; Lim, S.C.; Smakowski, P.; Park, J.Y.; King, G.L.; LoGerfo, F.W.; Horton, E.S.; Veves, A. Microvascular and macrovascular reactivity is reduced in subjects at risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 1999, 48, 1856-1862, doi:10.2337/diabetes.48.9.1856.

- Carrizzo, A.; Izzo, C.; Oliveti, M.; Alfano, A.; Virtuoso, N.; Capunzo, M.; Di Pietro, P.; Calabrese, M.; De Simone, E.; Sciarretta, S., et al. The Main Determinants of Diabetes Mellitus Vascular Complications: Endothelial Dysfunction and Platelet Hyperaggregation. International journal of molecular sciences 2018, 19, doi:10.3390/ijms19102968.

- Thorand, B.; Baumert, J.; Chambless, L.; Meisinger, C.; Kolb, H.; Doring, A.; Lowel, H.; Koenig, W.; Group, M.K.S. Elevated markers of endothelial dysfunction predict type 2 diabetes mellitus in middle-aged men and women from the general population. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology 2006, 26, 398-405, doi:10.1161/01.ATV.0000198392.05307.aa.

- Lim, S.C.; Caballero, A.E.; Smakowski, P.; LoGerfo, F.W.; Horton, E.S.; Veves, A. Soluble intercellular adhesion molecule, vascular cell adhesion molecule, and impaired microvascular reactivity are early markers of vasculopathy in type 2 diabetic individuals without microalbuminuria. Diabetes care 1999, 22, 1865-1870, doi:10.2337/diacare.22.11.1865.

- Festa, A.; D'Agostino, R., Jr.; Tracy, R.P.; Haffner, S.M.; Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis, S. Elevated levels of acute-phase proteins and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 predict the development of type 2 diabetes: the insulin resistance atherosclerosis study. Diabetes 2002, 51, 1131-1137, doi:10.2337/diabetes.51.4.1131.

- Vischer, U.M.; Emeis, J.J.; Bilo, H.J.; Stehouwer, C.D.; Thomsen, C.; Rasmussen, O.; Hermansen, K.; Wollheim, C.B.; Ingerslev, J. von Willebrand factor (vWf) as a plasma marker of endothelial activation in diabetes: improved reliability with parallel determination of the vWf propeptide (vWf:AgII). Thrombosis and haemostasis 1998, 80, 1002-1007.