The citizen-centric smart city is conceptualised from the citizenship perspective which stressed on the citizen's responsibilities and participatory governance practices in a smart city (Malek, Lim and Yigitcanlar, 2021). This conception argues that instead of the traditional view on fulfilling the citizen's needs, the citizens should co-produce, participate and contribute to building the smart city together with the government and corporates.

- citizen centrism

- citizen-centric smart cities

- urban studies

- participatory governance

- neoliberal urbanism

- public participation

- participatory planning

- right to the city

- smart city

- smart citizenship

- social inclusion indicator

- sustainable urban development

1. Introduction

To date, considering citizens’ perceptions about and perspectives of smart city development is seen as a sound strategy for many political and administrative leaders. Particularly, this has taken the form of promoting eGov (citizen centricity in e-government) that has been upheld in Europe since the mid-2000s [10] and is rooted in the perspective of “citizens as customers” under the new public management [11]. Based on this influence, apart from technological needs or smart cities, in recent years, city administrators have shifted their focus to co-creating smart cities with their citizens [12][13][14][15].

The rhetorical smart city visions in emerging and developing countries [16][17], such as the slogans of the federal government of Malaysia and the state government of Selangor’s “Peduli Rakyat” (literally care for citizens) [9], have rightly inspired and motivated the general public, who are entirely depending on government resources or actions. Nevertheless, the targeted passive users, beneficiaries, or the public are unaware of their responsibilities, even though “citizen-centric smart city initiatives are rooted in stewardship, civic paternalism, and a neoliberal conception of citizenship” [10]. These neoliberal conceptions “prioritized choice of consumption and individual autonomy within a framework of state and corporate-defined constraints that focused on market-led solutions to urban issues, rather than being grounded in civil, social, and political rights, and the common good” [10]. In other words, the market-led solutions put a high dependency on corporate technological sectors in most of the current forms of smart urban governance and tokenize the proactive response from users/citizens [11]. More so, [12] rightly pointed out that the citizen-centred idea is less compatible with neoliberalism because local governance needs to prioritize offering incentives to investors if it is to compete within the world system of cities.

Furthermore, in studies that investigated citizen centricity in smarter cities [13], the main interest was concentrated on measuring a citizen-centric approach by monitoring cities’ abilities to safeguard citizenship rights. However, in a more holistic view of the citizenship regime [14], citizenship should include rights, governance practices, and citizens’ responsibilities. Additionally, some recent studies [15][16] revealed that the current British Smart City Standards and the Malaysia Smart City Framework have an explicit citizenship rationale for guiding the standards and development of a smart city, although these guidelines displayed some substantial shortcomings and contradictions.

These shortcomings include superficial and unclear explanations of the citizenship regime in forming a citizen-centric smart city and contradictions in citizens’ priorities against the profit gained from technological markets and the legitimacy of paternity governance.

2. The Conception of Citizen Centricity in Smart City Development

The notion of citizen centricity in (smart) city development is not a novel one and is perceived as a continuous trend in the development of e-government, which started in the mid-2000s. It is in line with the concept derived from new public management, where citizens should be viewed as customers to improve public service delivery. As customers, the demands of services have implications that are likely to turn citizens into passive users or beneficiaries who receive and demand from public administrators. It was argued that in constructing a citizen-centric smart city (CCSC), there should be no generalizations in viewing citizens as customers. In fact, there is a need to seriously research and construct a CCSC from the perspectives of both citizenships (to explain the notion of citizen centricity) and literature on the conception of the smart city conception.

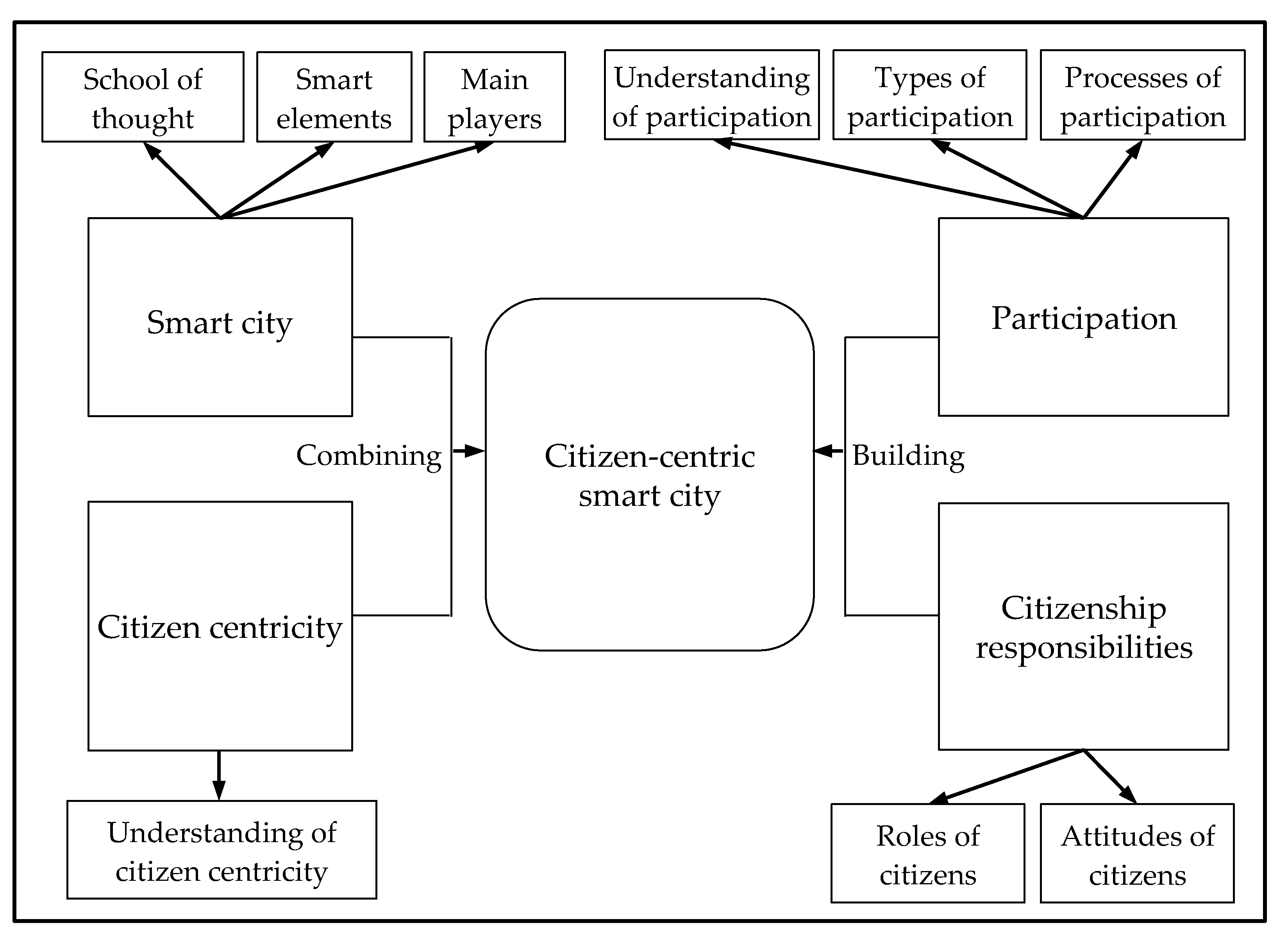

The theoretical framework of a CCSC formed by Malek et al. (2021) is the first structured framework of its kind in the literature on smart cities (Figure 1). This CCSC theoretical framework thoroughly explains the original combination of the source of references for the notion of citizen centricity and the smart city concept. From these combinations, it was revealed that the construction of such detailed indicators and citizenship conception should include three major components, namely, citizens’ rights (not included in this study, as it was already detailed by [13][17]), citizens' responsibilities, and the practices of citizen participation in governance. This framework is unique, as the framework is viewed from a fundamental perspective of what citizens can contribute to the formation of a CCSC. The focus of the indicators originated from the perspective of the citizens rather than the government’s point of view. Such a perspective would make the role of citizens proactive and similar to the conception of self-organizing cities [18][19][20], which developed beyond the current neoliberal smart cities.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework (source: authors). Smart city [21][22]; Participation [23][24][25]; Citizen-centric smart city [26]; Citizen centricity [1][27]; Citizenship responsibilities [14][28].

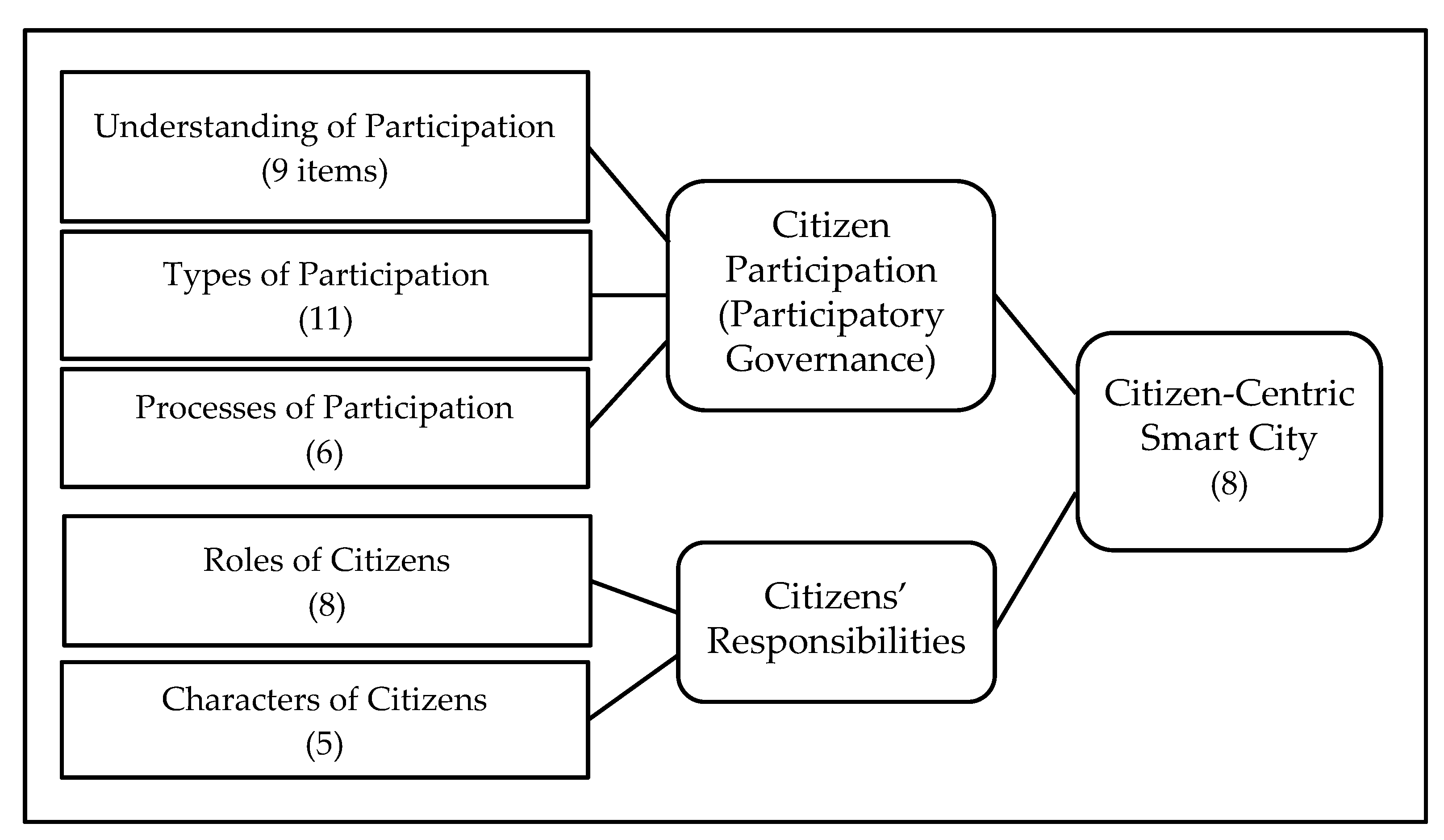

From such a theoretical framework, Malek et al. (2021) has attempted to construct a conceptual framework consisting of six constructs and 47 items (Figure 2). All the constructs were verified carefully by 38 practitioners in the fields of smart city development and community participation. The first stage of the formation of indicators was derived from the majority of literature reviews from scholars in developed Western countries, hence outlining the holistic scope of citizenship notions. Moreover, practitioners from emerging and developing countries with comparatively lower democracy and citizenship conceptions, such as Malaysia, tended to agree with all the indicators from the Western literature and included additional examples from the local context to gain a better understanding of the residents. Thus, the design of such indicators could be said to suit both developed and developing countries. Concerning future implementations, the examples of particular items should be altered with caution to suit other local contexts.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework for a citizen-centric smart city (source: authors).

Malek et al. (2021) predict that further studies on empirical survey results could yield a less significant result on some indicators, as the mindset and acceptance of democracy and the rights in emerging and developing countries, such as Malaysia, could be lower compared to developed countries. Hence, the full acceptance of the indicators is not possible, as the democratic innovations of developing countries are faced with challenges and restrictions [30]. The proposed democratic innovation includes expanding the role of citizens as co-producers [31], which is rarely practised in developing countries. Furthermore, with regard to the usage of political slogans in building a CCSC, leaders may appear insincere if people are tokenized as customers with needs to fulfil but not cultivated and given the opportunities to participate in governance practices. Thus, Malek et a. (2021) are fully aware of the challenges and costs of participatory and deliberative governance [29]. However, to intervene in such neoliberal smart urbanism [32] and realize the possibility of “self-organizing” smart cities, these CCSC indicators are worthy of reference and can be modified in different contexts.

The potential self-organizing cities led by local stakeholders could emerge as responses to unsatisfactory government-driven processes, market failures [33], the intention to legitimize a government’s retreat from sectors that have traditionally played a vital role [33], or the intervention of e-participation through digital technologies [34][35]. This self-organizing and more democratic realm of a CCSC has led to three levels of discussion. The first level is the democratic culture of a country, the leaders’ understanding, and the delegation of decision-making power in governance. The second level is society’s perception of citizenship, the participative culture of societies, and the lack of links to decision-making [36]. The third level is the individual citizens’ discipline and contributions to the country or city.

For an emerging and developing country like Malaysia, the dual forms of Islamic and secular administrations and constitutions are often criticized by scholars in the context of democracy [37][38][39]. Such a context hints that the highest constitution is not as open to democracy as practised by Western countries. Canada, for example, has the Citizenship Act, the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the Multiculturalism Act [40][41][42], as opposed to Malaysia. Another example is the Nordic welfare society in the context of a democratic culture, welfarism, and redistributive policies that provide support to the development of participatory and innovative platforms by strengthening social inclusion, regulating the growth mechanisms, and easing the tensions between pro-growth and anti-growth coalitions [43].

In Malaysia, “participatory governance practice” is a tokenized term under the current top-down policy governance practices. The majority of government administrators “listen” and act according to political masters, but less focus is given to grassroots suggestions [44][45]. The lack of participatory governance practices was also similar to other developing countries, such as India, China, and Egypt [46][47]. In developing India’s 100 smart cities, [46] questioned the liberal electoral democracy in India on the exten[48]t to which a smart city can deliver de facto inclusion and participation. [49] added that, instead of testing Indian smart cities as the grounds for democratic participation, smart citizens were nudged as subaltern citizens in urban governance. In China’s smart-eco city projects, [50] reported that citizen input in the decision-making phase was quite limited, hence suggesting legislative reforms and the professionalization of Chinese officials in dealing with bottom-up input. In Egypt, [47] recommended that the Egyptian government focus specifically on smart people, such as giving citizens equal opportunity to participate in public decision-making.

Suppose the future survey results of the proposed indicators in this study receive high acceptance. In that case, participatory governance may become a new norm in local governance and mark a transition from party politics, expert dominance, and siloed bureaucracy to citizen participation, consequently supporting citizens’ efforts to co-produce public services and build potential self-organizing smart cities.

At the level of society, the culture of participation in government programs is considered to be low [9][48]. From studies based on the Petaling Jaya and Cyberjaya smart city cases [9], the low level of participation was not interpreted based on the moderate quantity of participative programs involving citizens in the implementation stages, but the interpretation was based on the particularly low (even none) quantity of programs that empowered citizens at the initial stage of decision-making. The situation in Malaysia resembles making “decision by decision,” where the community has no liberty to decide, is constrained by decisions from authorities, and is at the mercy of the authorities [9]. Furthermore, as described by [51], in the context of Amsterdam and Amersfoort, The Netherlands, “self-organization seems to take place in the shadow of a government hierarchy: either a fear-based one or a benevolent one,” particularly in the context of meta-governance. In the context of Helsinki, Finland, self-organization also lacked links to decision-making, thus constraining new solutions and creative actions [36].

Such contexts indicated that society’s mindset is still conservative, with a vague understanding of the citizenship’s regime, leading to a possibly high dependency of people on the government. The evidence in Malaysia, such as the withdrawal of participation from the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court [52] and the human rights issues evoked by racially and religiously motivated political parties, had correctly signalled the relatively low appreciation of equality in human rights when race- and religion-based interests are challenged.

At the level of individual Malaysian citizens, people’s self-discipline would increase with the realization of a CCSC. For example, the role of volunteers, local champions, and co-producers with characteristics of proactiveness and awareness of CCSC development are all important responsibilities that a citizen has to contribute to building a CCSC. In a potential majority of highly responsible citizens, this contributes to the building of sustainable and inclusive societies, cities, and a wider scope of progressiveness in Malaysia.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13010376

References

- Lim, S.B. Membina Model Bandar Pintar Berpusatkan Rakyat di Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cardullo, P.; Kitchin, R. Being a ‘citizen’ in the smart city: Up and down the scaffold of smart citizen participation in Dublin, Ireland. GeoJournal 2019, 84, doi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kummitha, R.K.R. Entrepreneurial urbanism and technological panacea: Why Smart City planning needs to go beyond corporate visioning? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 137, 330–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, S. The Just City; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Marsal-Llacuna, M.-L. City indicators on social sustainability as standardization technologies for smarter (citizen-centered) governance of cities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2016, 128, 1193–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, J. Redesigning citizenship regimes after Neoliberalism. Moving towards Social Investment. In What Future for Social Investment? Morel, N., Palier, B., Palme, J., Eds.; Institute for Future Studies: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, S.; Cook, M.; Dayot, Y. Smart cities: Towards a new citizenship regime? A discourse analysis of the British Smart City Standard. J. Urban Technol. 2017, 24, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.B.; Jalaluddin, A.M.; Mohd Yusof, H.; Zurinah, T. Malaysia Smart City Framework: A trusted framework for shaping smart Malaysian citizenship? In Handbook of Smart Cities; Augusto, J.C., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsal-Llacuna, M.-L. Building universal socio-cultural indicators for standardizing the safeguarding of citizens’ rights in smart cities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 130, 563–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Undheim, T.A.; Blakemore, M. A Handbook for Citizen-Centric eGovernment; Version 2.1; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hood, C. The “New Public Management” in the 1980s: Variations on a theme. Account. Organ. Soc. 1995, 20, 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Hoogen, A.; Scholtz, B.; Calitz, A.P. Using theories to design a value alignment model for smart city initiatives. In International Federation for Information Processing; Hattingh, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG). Executive Summary of Co-creating the Urban Future: The Agenda of Metropolises, Cities and Territories; UCLG: Barcelona, Spain, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nabatchi, T.; Sancino, A.; Sicilia, M. Varieties of participation in public services: The who, when, and what of Coproduction. Public Adm. Rev. 2017, 77, 766–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allwinkle, S.; Cruickshank, P. Creating smart-er cities: An overview. J. Urban Technol. 2011, 18, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, V. The allure of ‘smart city’ rhetoric: India and Africa. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2015, 36–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, A. A 100 smart cities, a 100 utopias. Dialogues Hum. Geogr. 2015, 5, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savini, F. Self-organization and urban development: Disaggregating the city-region, deconstructing urbanity in Amsterdam. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 1152–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterlynck, S.; González, S. “Don’t waste a crisis”: Opening up the city yet again for neoliberal experimentation. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2013, 37, 1075–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabannes, Y.; Douglass, M.; Padawangi, R. Cities by and for the People; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giffinger, R.; Fertner, C.; Kramar, H.; Kalasek, R.; Pichler, N.; Meijers, E. Smart Cities: Ranking of European Medium-Sized Cities; TU Vienna: Wien, Astria, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nam, T.; Pardo, T. Conceptualizing smart city with dimensions of technology, people & institutions. In Proceedings of the 12th Annual International Conference on Digital Government Research, College Park, MD, USA, 12–15 June 2011; pp. 282–291. [Google Scholar]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcox, D. The Guide to Effective Participation; Delta Press: Brighton, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bovaird, T. Beyond engagement and participation: User and community coproduction of public services. Public Adm. Rev. 2007, 67, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardullo, P.; Kitchin, R. Being a ‘Citizen’ in the Smart City: Up and down the Scaffold of Smart Citizen Participation; Programmable City Working Paper No. 30; National University of Ireland Maynooth: County Kildare, Ireland, 15 May 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen, L.; Johannesen, M.R.; Ødegård, A. A citizen-centric public sector: Why citizen centricity matters and how to obtain it. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Advances in Human-oriented and Personalized Mechanisms, Technologies, and Services (AHPMTS), Rome, Italy, 21–25 August 2016; pp. 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen, L.; Johannessen, M.R. The role of citizens in “smart cities”. In Proceedings of the Management International Conference, University of Presov; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Jalaluddin, A.M.; Lim, S.B.; Zurinah, T. Understanding the issues of citizen participation. J. Nusant. Stud. 2019, 4, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikami, N. Trends in democratic innovation in Asia. In Handbook of Democratic Innovation and Governance; Elstub, S., Escobar, O., Eds.; Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; pp. 421–434. [Google Scholar]

- Rotta, M.J.R.; Sell, D.; dos Santos Pacheco, R.C.; Yigitcanlar, T. Digital commons and citizen coproduction in smart cities: Assessment of Brazilian municipal e-government platforms. Energies 2019, 12, 2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardullo, P.; Di Feliciantonio, C.; Kitchin, R. The Right to the Smart City; Emerald: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonstra, B.; Boelens, L. Self-organization in urban development: Towards a new perspective on spatial planning. Urban Res. Pract. 2011, 4, 99–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, P.M. Cities and Regions as Self-Organizing Systems: Models of Complexity; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portugali, J. Self-Organization and the City; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horelli, L.; Saad-Sulonen, J.; Wallin, S.; Botero, A. When self-organization intersects with urban planning: Two cases from Helsinki. Plan. Pract. Res. 2015, 30, 286–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsul, A.B. Nations-of-Intent in Malaysia. In Asian Forms of Nations; Tonnesson, S., Antlov, H., Eds.; Curzon: London, UK, 1996; pp. 323–347. [Google Scholar]

- Abdul Mutalib, M.F.M.; Wan Zakaria, W.F.A. Pasca-Islamisme dalam PAS: Analisis terhadap kesan Tahalluf Siyasi. Int. J. Islam. Thought. 2015, 8, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Attas, S.M.N. Islam and Secularism; Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Canada Government. Canadian Citizenship Act. 1947. Available online: https://pier21.ca/research/immigration-history/canadian-citizenship-act-1947#footnote-6 (accessed on 10 December 2019).

- Goodman, N.; Zwick, A.; Spicer, Z.; Carlsen, N. Public engagement in smart city development: Lessons from communities in Canada’s Smart City Challenge. Can. Geogr./Le Géographe. Can. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenson, J. Fated to live in interesting times: Canada’s changing citizenship regimes. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 1997, 30, 627–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anttiroiko, A. City-as-a-platform: The rise of participatory innovation platforms in Finnish cities. Sustainability 2016, 8, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.S.; Kalianan, M. From customer satisfaction to citizen satisfaction: Rethinking local government service delivery in Malaysia. Asian Soc. Sci. 2008, 4, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, J. History and context of public administration in Malaysia. In Public Administration in Southeast Asia: Thailand, Philippines, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Macao; Berman, E.M., Ed.; Taylor & Francis: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011; pp. 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoelscher, K. The evolution of the smart cities agenda in India. Int. Area Stud. Rev. 2016, 19, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, K. Smart city implementation framework for developing countries: The case of Egypt. In Smarter as the New Urban Agenda; A Comprehensive View of the 21st Century City; Gil-Garcia, J.R., Pardo, T.A., Nam, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland; pp. 171–187. [CrossRef]

- Mariana, M.O. Stakeholder Participation in the Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in Malaysia. Ph.D. Thesis, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Seri Kembangan, Malaysia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, A. The digital turn in postcolonial urbanism: Smart citizenship in the making of India’s 100 smart cities. Trans Inst Br Geogr. 2018, 43, 405–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Hu, Y. Planning for sustainability in China’s urban development: Status and challenges for Dongtan eco-city project. J. Environ. Monit. 2010, 12, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nederhand, J.; Bekkers, V.; Voorberg, W. Self-organization and the role of government: How and why does self-organization evolve in the shadow of hierarchy? Public Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 1063–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, E. Foreign and Security Policy in the New Malaysia. Available online: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/foreign-and-security-policy-new-malaysia#sec41256 (accessed on 8 September 2020).

- Noor, E. Foreign and Security Policy in the New Malaysia. Available online: https://www.lowyinstitute.org/publications/foreign-and-security-policy-new-malaysia#sec41256 (accessed on 8 September 2020).