Studies suggest that migraine pain has a vascular component. The prevailing dogma is that peripheral vasoconstriction activates baroreceptors in central, large arteries. Dilatation of central vessels stimulates nociceptors and induces cortical spreading depression. Studies investigating nitric oxide (NO) donors support the indicated hypothesis that pain is amplified when acutely administered. We provide an alternate hypothesis which, if substantiated, may provide therapeutic opportunities for attenuating migraine frequency and severity. We suggest that in migraines, heightened sympathetic tone results in progressive central microvascular constriction. Suboptimal parenchymal blood flow, we suggest, activates nociceptors and triggers headache pain onset. Administration of NO donors could paradoxically promote constriction of the microvasculature

as a consequence of larger upstream central artery vasodilatation. Inhibitors of NO production are reported to alleviate migraine pain. We describe how constriction of larger upstream arteries, induced by NO synthesis inhibitors, may result in a compensatory dilatory response of the microvasculature. The restoration of central capillary blood flow may be the primary mechanism for pain relief. Attenuating the propensity for central capillary constriction and promoting a more dilatory phenotype may reduce frequency and severity of migraines. We propose consideration of two dietary nutraceuticals for reducing migraine risk: L-arginine and aged garlic extracts.

- aged garlic extract

- calcium

- L-arginine

- migraine

- nitric oxide

- vasodilation

- vasoconstriction

1. Introduction

Migraine is the most common and one of the costliest neurological disorders to treat [1][2]. Migraines are described to occur through a stress-induction pathway and may, in some individuals, represent a continuum of tension headaches [3]. As a global health burden, migraines have an estimated worldwide prevalence of 1.04 billion with a staggering disability-adjusted life burden of approximately 45.1 million years per annum [4]. The aetiology of migraines is not entirely clear; however, there is a body of opinion which suggests that pain in migraine is associated with vasodilatation of large cerebral arteries [5]. This hypothesis is paradoxical, as dilatation of large cerebral arteries is not suggested by studies examining net change in cerebral blood flow in migraine sufferers. Rather, the latter would suggest that, along with dilatation of large arteries, there is downstream vasoconstriction of the cerebral microcirculation, raising an alternate consideration of causation [6].

2. A Revised Hypothesis for the Pathophysiology of Vascular-Based Migraines

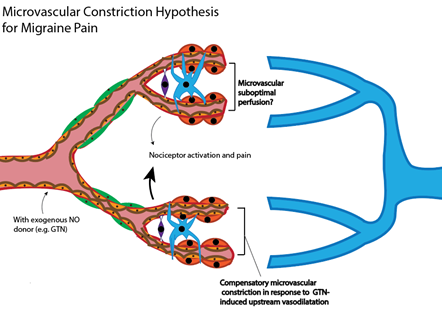

We present an alternate hypothesis with respect to purported cerebrovascular changes in the aetiology of migraines. The hypothesis reconciles the vascular paradoxes described. We propose that as a consequence of stress-induced heightened sympathetic tone, or as a consequence of endocrine mediators (such as depletion of plasma oestrogen during menorrhoea), microvascular blood flow is compromised, not only in peripheral vascular beds, but also within the central microvasculature (Figure 1). Suboptimal central parenchymal blood flow, or indeed pseudo-hypoxia, may activate cranial nociceptors and cause headache. The acute intravenous provision of exogenous NO donors, such as GTN, will promote upstream central larger artery dilatation (Figure 1). To respond to upstream vasodilatation and critically maintain parenchymal perfusion pressure within the central microvasculature, capillaries must further constrict. The microvascular response of constriction would exacerbate the pre-existing suboptimal parenchymal flow in regional areas of high energy demand, effectively amplifying nociceptor activation and pain intensity [7]. The acute provision of NOS inhibitors to treat migraine will result in central large artery constriction, concomitant with increased heart rate. In response, downstream parenchymal microvessels would need to vasodilate in order to maintain perfusion pressure within an optimal range. The latter would restore microvascular blood flow. The restoration of flow provides nutrients and oxygen, and there is alleviation of pain.

Figure 1. Alternate hypothesis for vascular changes in migraine. Stress-induced heightened sympathetic tone results in a chronically constrictive microvascular phenotype, both centrally and within the periphery. Suboptimal central parenchymal blood flow (potential hypoxia) could activate nociceptors and cause headache pain onset. Traditional NO donors (such as GTN) principally modulate upstream larger central arteries, and would only exacerbate downstream vasoconstriction. Provision of eNOS inhibitors will reduce blood flow to the brain through larger arteries, requiring compensatory downstream dilatation of capillaries. The latter restores the provision of nutrients and oxygen.

3. L-arginine and Aged Garlic Extract as Parenchymal Vasodilators

L-arginine is a precursor for the vasodilator NO [8], and studies have shown an association between vascular tone and plasma concentrations of L-arginine [9]. In physiological conditions, the L-arginine molecule consists of a protonated α-amino group, a deprotonated α-carboxylic acid group, a 3-carbon aliphatic straight side chain, and ends with a protonated guanidino group [10]. NO production by vascular endothelial cells is enhanced by L-arginine, as NO is formed from the terminal guanidino-N atoms in L-arginine [10]. This involves two steps: mobilisation of L-arginine and conversion to NO—both of which are activated by bradykinin and the calcium ionophore A23187 [10]. In particular, it is the extracellular L-arginine which induces endothelial NO synthesis, not intracellular abundance.

Aged garlic extract (AGE, Kyolic, Allium sativum) is a capillary inflammation inhibitor [11] with the relevant active component, S-allyl-cysteine ((R)-2-amino-3-prop-2-enylsulfanylpropanoic acid; S-2-propenyl-L-cysteine; S-allyl-laevo-cysteine; S-allylcysteine) [12], which comprises the amino acid cysteine with an allyl group attached to its sulphur atom. AGE is prepared by extracting sliced raw garlic and storing it in 15–20% ethanol at room temperature for 20 months, increasing antioxidant activity [11]. There are ~1000 micrograms per gram of S-allyl-cysteine in AGE, but only 20 micrograms per gram of S-allyl-cysteine in raw garlic [12]. AGE enhances NO synthesis, promoting vasodilatation[13]; however, indirect positive effects on vessel diameter have been proposed because of its potent antioxidant, antithrombotic, and antiatherosclerotic effects [14]. Despite AGE demonstrating antiplatelet effects, there has been no increased bleeding risk in patients concurrently taking blood-thinning medication [15].

4. Vasodilatory Effects of L-arginine

We found no studies that reported on the effects of L-arginine in the context of migraine. We reviewed animal studies to ascertain the reported vascular effects of L-arginine. To determine whether these effects extended to humans, we then conducted a search of completed clinical studies from 2009 to 2019 using L-arginine. Similar effects were noted. Moreover, only mild gastrointestinal effects were reported in humans. In summary, L-arginine is worth investigating as a prophylactic migraine medication, due to its potential role in the NO vasodilatory pathway. Doses of 3–8 g per day appear safe in humans [8]. However, individual patient response also depends on endogenous asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) levels, as it competes with (and therefore inhibits) NO synthase, which synthesises NO from L-arginine [16]. In patients with high ADMA, L-arginine seems to restore endothelial function to a vasodilating normal by increasing NO synthesis via NO synthase [16]. A study showed a linear correlation between L-arginine:ADMA ratio and pain-free walking distance [9]. Upon the addition of L-arginine, the L-arginine:ADMA ratio is normalised [16]. As with most disease conditions, earlier treatment has been recommended for better results, measured by changes in vascular function [8]. According to our proposed alternate hypothesis, dietary L-arginine should reduce blood pressure and promote tissue perfusion by promoting microvascular dilatation via enhanced biosynthesis of endothelial NO. By extension, provision of dietary L-arginine might be an effective strategy for attenuating frequency/severity of vascular-based migraines.

5. Vasodilatory Effects of Aged Garlic Extract

We found no studies that reported on the effects of AGE in the context of migraine. Nonetheless, we first looked at animal studies to ascertain the vascular effects of AGE. To see if these effects extended to humans, we then conducted a search of completed clinical studies during the same period. In summary, the body of evidence suggests that AGE could be a suitable candidate for vascular-induced migraine therapy; however, this would need to be tested, preferably through randomised controlled trials. As seen here, garlic extracts have been investigated widely as potential treatments for cardiovascular diseases [17]. Moreover, garlic-derived therapeutics have minimal adverse effects, with the major ones being limited to halitosis and bromhidrosis [18]. Halitosis applies when the raw form of garlic is used [19], whereas AGE is odourless [12]. Potential side effects of AGE include nausea and vomiting [19]. Due to its fibrinolytic property, bleeding events can potentially occur [20], so its dose has to be monitored [21]. Only 3 studies mentioned adverse side effects of AGE[15][22][23]. However, these gastrointestinal symptoms were minor, short-lived, and readily managed by the subjects [15][22][23]. One study even reported improved digestion [15]. According to our proposed alternate hypothesis, dietary AGE should reduce blood pressure and promote tissue perfusion by promoting microvascular dilatation by inhibiting vasoconstrictive factors. By extension, provision of dietary AGE might be an effective strategy for attenuating frequency/severity of migraines.

6. Conclusions

Given the positive action on vasodilatation exerted by L-arginine and AGE in the above cardiovascular studies, we surmise that these agents should be investigated in future randomised controlled trials for prevention of migraines induced by cerebral microvascular constriction. To assess and confirm regional vasoconstriction of cerebral arterioles and capillaries, we recommend imaging of the cerebral microvasculature directly using functional imaging techniques [24]. L-arginine is also present as a minor component in AGE. Although new treatments and preventions are being explored for migraine treatment [25][26], L-arginine and AGE have not been clinically considered. One limitation is that presently, no studies investigated the effects of L-arginine and AGE in the context of gender or ageing. These variables are established risk factors for headaches, concomitant with decreased endogenous biosynthesis of NO. We did not address the effects of L-arginine and AGE on inflammation or oxidative damage, lipids, or thrombotic activity, which can also affect vessel diameter. However, all studies showed an alleviating effect of both L-arginine and AGE in all 3 aspects: decreased inflammation and oxidative damage markers, decreased triglycerides and low-density lipoproteins, increased high-density lipoproteins, decreased atherosclerosis, and decreased thrombotic events. The fact that neither L-arginine nor AGE have been tried in randomised controlled trials, specifically for the prevention of migraine, is a current shortcoming. Reported well-tolerated doses of L-arginine and AGE, considered for cardiovascular disease risk, serve as a useful guide to explore the putative efficacy of L-arginine and AGE for prevention/treatment of vascular-associated migraine.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu12082487

References

- Patrik Andlin-Sobocki; Bengt Jonsson; Hans-Ulrich Wittchen; Jamie D. Olesen; Cost of disorders of the brain in Europe. European Journal of Neurology 2005, 12, 1-27, 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2005.01202.x.

- Matilde Leonardi; T. J. Steiner; Ann I Scher; R. B. Lipton; The global burden of migraine: measuring disability in headache disorders with WHO's Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). The Journal of Headache and Pain 2005, 6, 429-440, 10.1007/s10194-005-0252-4.

- Sara C. Crystal; Matthew S. Robbins; Epidemiology of Tension-type Headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2010, 14, 449-454, 10.1007/s11916-010-0146-2.

- Lars Jacob Stovner; Emma Nichols; Timothy J Steiner; Foad Abd-Allah; Ahmed Abdelalim; Rajaa M Al-Raddadi; Mustafa Geleto Ansha; Aleksandra Barac; Isabela M Bensenor; Linh Phuong Doan; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 2018, 17, 954-976, 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3.

- Patrick P.A. Humphrey; Wasyl Feniuk; Mode of action of the anti-migraine drug sumatriptan. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 1991, 12, 444-446, 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90630-b.

- Jamie D. Olesen; Nitric oxide-related drag targets in headache. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 183-190, 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.006.

- Simon Akerman; David J Williamson; Holger Kaube; Peter J. Goadsby; The effect of anti-migraine compounds on nitric oxide-induced dilation of dural meningeal vessels. European Journal of Pharmacology 2002, 452, 223-228, 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02307-5.

- Rainer H Böger; The pharmacodynamics of L-arginine.. Alternative therapies in health and medicine 2014, 20, 48-54, .

- R H Böger; Stefanie M. Bode-Böger; Wolfgang Thiele; Andreas Creutzig; Klaus Alexander; Jürgen C Frölich; Restoring vascular nitric oxide formation by L-arginine improves the symptoms of intermittent claudication in patients with peripheral arterial occlusive disease.. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 1998, 32, 1336-1344, 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00375-1.

- R. M. J. Palmer; D. S. Ashton; S. Moncada; Vascular endothelial cells synthesize nitric oxide from L-arginine. Nature 1988, 333, 664-666, 10.1038/333664a0.

- Ryu Takechi; Menuka M Pallebage-Gamarallage; Virginie Lam; Corey Giles; John Mamo; Nutraceutical agents with anti-inflammatory properties prevent dietary saturated-fat induced disturbances in blood–brain barrier function in wild-type mice. Journal of Neuroinflammation 2013, 10, 842-73, 10.1186/1742-2094-10-73.

- Carmia Borek; Antioxidant health effects of aged garlic extract.. The Journal of Nutrition 2001, 131, 1010S-1015S, 10.1093/jn/131.3.1010s.

- Naoaki Morihara; Isao Sumioka; Toru Moriguchi; Naoto Uda; Eikai Kyo; Aged garlic extract enhances production of nitric oxide. Life Sciences 2002, 71, 509-517, 10.1016/s0024-3205(02)01706-x.

- Naoaki Morihara; Mitsuyasu Ushijima; Naoki Kashimoto; Isao Sumioka; Takeshi Nishihama; Minoru Hayama; Hidekatsu Takeda; Aged Garlic Extract Ameliorates Physical Fatigue. Biological and Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2006, 29, 962-966, 10.1248/bpb.29.962.

- Michael J.A. Williams; Wayne H. F Sutherland; Maree P. McCormick; David J. Yeoman; Sylvia A. De Jong; Aged garlic extract improves endothelial function in men with coronary artery disease. Phytotherapy Research 2005, 19, 314-319, 10.1002/ptr.1663.

- Stefanie M. Bode-Böger; Jochen Muke; Andrzej Surdacki; Georg Brabant; Rainer H Böger; Jürgen C Frölich; Oral L-arginine improves endothelial function in healthy individuals older than 70 years.. Vascular Medicine 2003, 8, 77-81, 10.1191/1358863x03vm474oa.

- Kerstin Breithaupt-Grögler; Michael Ling; Harisios Boudoulas; Gustav G. Belz; Protective Effect of Chronic Garlic Intake on Elastic Properties of Aorta in the Elderly. Circulation 1997, 96, 2649-2655, 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2649.

- S. K. Banerjee; Pulok K. Mukherjee; S. K. Maulik; Garlic as an antioxidant: the good, the bad and the ugly. Phytotherapy Research 2003, 17, 97-106, 10.1002/ptr.1281.

- Ronald T. Ackermann; Cynthia D. Mulrow; Gilbert Ramirez; Christopher D. Gardner; Laura Morbidoni; Valerie A. Lawrence; Garlic shows promise for improving some cardiovascular risk factors.. Archives of Internal Medicine 2001, 161, 813-824, 10.1001/archinte.161.6.813.

- Bongiorno, P.B.; Potential health benefits of garlic (Allium sativum): A narrative review . J. Complement. Integr. Med. 2008, 5, 1, .

- Larisa Chagan; Anna Ioselovich; Liya Asherova; Judy W M Cheng; Use of alternative pharmacotherapy in management of cardiovascular diseases.. The American Journal of Managed Care 2002, 8, 286-278, .

- Vahid Nabavi Larijani; Naser Ahmadi; Irfan Zeb; Faraz Khan; Ferdinand Flores; Matthew J. Budoff; Beneficial effects of aged garlic extract and coenzyme Q10 on vascular elasticity and endothelial function: the FAITH randomized clinical trial.. Nutrition 2012, 29, 71-5, 10.1016/j.nut.2012.03.016.

- Karin Ried; Nikolaj Travica; Avni Sali; The Effect of Kyolic Aged Garlic Extract on Gut Microbiota, Inflammation, and Cardiovascular Markers in Hypertensives: The GarGIC Trial. Frontiers in Nutrition 2018, 5, 122, 10.3389/fnut.2018.00122.

- Van Zijl, P.C.; Eleff, S.M.; Ulatowski, J.A.; Oja, J.M.; Uluǧ, A.M.; Traystman, R.J.; Kauppinen, R.A. Quantitative assessment of blood flow, blood volume and blood oxygenation effects in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 159–167.

- Allison, G.L.; Lowe, G.M.; Rahman, K. Aged garlic extract and its constituents inhibit platelet aggregation through multiple mechanisms. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 782S–788S.

- Schuster, N.M.; Rapoport, A.M. New strategies for the treatment and prevention of primary headache disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 635.

- Sara C. Crystal; Matthew S. Robbins; Epidemiology of Tension-type Headache. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2010, 14, 449-454, 10.1007/s11916-010-0146-2.

- Lars Jacob Stovner; Emma Nichols; Timothy J Steiner; Foad Abd-Allah; Ahmed Abdelalim; Rajaa M Al-Raddadi; Mustafa Geleto Ansha; Aleksandra Barac; Isabela M Bensenor; Linh Phuong Doan; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet Neurology 2018, 17, 954-976, 10.1016/s1474-4422(18)30322-3.

- Patrick P.A. Humphrey; Wasyl Feniuk; Mode of action of the anti-migraine drug sumatriptan. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 1991, 12, 444-446, 10.1016/0165-6147(91)90630-b.

- Jamie D. Olesen; Nitric oxide-related drag targets in headache. Neurotherapeutics 2010, 7, 183-190, 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.006.

- Van Zijl, P.C.; Eleff, S.M.; Ulatowski, J.A.; Oja, J.M.; Uluǧ, A.M.; Traystman, R.J.; Kauppinen, R.A. Quantitative assessment of blood flow, blood volume and blood oxygenation effects in functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 159–167.

- Allison, G.L.; Lowe, G.M.; Rahman, K. Aged garlic extract and its constituents inhibit platelet aggregation through multiple mechanisms. J. Nutr. 2006, 136, 782S–788S.

- Schuster, N.M.; Rapoport, A.M. New strategies for the treatment and prevention of primary headache disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2016, 12, 635.