Klebsiella pneumoniae is an opportunistic pathogen that causes nosocomial and community-acquired infections. The spread of resistant strains of K. pneumoniae represents a growing threat to human health, due to the exhaustion of effective treatments. K. pneumoniae releases outer membrane vesicles (OMVs). OMVs are a vehicle for the transport of virulence factors to host cells, causing cell injury. Previous studies have shown changes of gene expression in human bronchial epithelial cells after treatment with K. pneumoniae OMVs. These variations in gene expression could be regulated through microRNAs (miRNAs), which participate in several biological mechanisms. Thereafter, miRNA expression profiles in human bronchial epithelial cells were evaluated during infection with standard and clinical K. pneumoniae strains. Microarray analysis and RT-qPCR identified the dysregulation of miR-223, hsa-miR-21, hsa-miR-25 and hsa-let-7g miRNA sequences. Target gene prediction revealed the essential role of these miRNAs in the regulation of host immune responses involving NF-ĸB (miR-223), TLR4 (hsa-miR-21), cytokine (hsa-miR-25) and IL-6 (hsa-let-7g miRNA) signalling pathways. The current study provides the first large scale expression profile of miRNAs from lung cells and predicted gene targets, following exposure to K. pneumoniae OMVs. Our results suggest the importance of OMVs in the inflammatory response.

- Klebsiella pneumoniae

- outer membrane vesicles

- inflammatory

- miRNAs

- antibiotic resistance

Note:All the information in this draft can be edited by authors. And the entry will be online only after authors edit and submit it.

1. Introduction

K. pneumoniae is a significant opportunistic pathogen, mainly associated with hospital-acquired infections [1]. Studies have estimated that it causes 8% of all nosocomial bacterial infections in Europe and in the United States [2,3]. This bacterium is responsible for a broad spectrum of extraintestinal diseases such as sepsis, pneumonia, urinary tract, lungs, abdominal cavity and soft tissue infections [4]. K. pneumoniae has important virulence factors, such as lipopolysaccharides, a capsule, adhesins and siderophores, required for its mechanism of colonization, adherence, invasion and to enable the progression of infection [2,5]. In addition, hemolysins, tyrosine kinase, heat-stable enterotoxins and heat-labile exotoxins participate in the pathogenicity [6,7]. K. pneumoniae rapidly acquires antibiotic resistance mechanisms making the selection of the appropriate antibiotic treatment more challenging [1,8]. Carbapenem resistance appears to have the greatest impact on the effectiveness of the treatment. The European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDCP) assumed that 15.2% of K. pneumoniae strains are carbapenem resistant in Italy [9,10]. In this scenario, nosocomial K. pneumoniae infections reflect a 50% mortality rate if untreated [11,12]. Given the clinical significance of this pathogen, a better understanding of other mechanisms of virulence is fundamental for designing new strategies to treat Klebsiella infections. It is well established that one of the characteristics of Gram-negative bacteria is their ability to form vesicles from the outer membrane, called outer-membrane vesicles (OMVs) [13–15]. OMVs are lipid bilayer spherical nanostructures with a diameter of 20–250 nm that are released into the host environment [16–18]. The surface of these vesicles is composed of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), phospholipids and outer membrane proteins [19,20]. The vesicular lumen, however, contains periplasmic and cytoplasmic components, including genetic material and virulence factors, such as invasion associated factors, toxins, and immune response modulators [21–23]. Thermolabile toxins and cytolysin have been identified in OMVs produced by Escherichia coli [24–26]. Haemolytic phospholipase C and alkaline phosphates have been detected in the OMVs of Pseudomonas aeruginosa [27–29]. Keenan et al. have found vacuolating cytotoxin A in the OMVs produced by Helicobacter pylori [18,30,31]. Since OMVs consist of toxins and several virulence determinants, it was postulated that the vesicles play a crucial role in bacteria–host interactions [32]. Previously, we demonstrated that OMVs of K. pneumoniae induce a strong inflammatory response in human bronchial epithelial cells (BEAS-2B) [13–15]. In these cells, OMVs strongly upregulate the expression of genes, encoding cytokines and chemokines [32]. In addition, the effect of the inflammatory cascade leads to pathogen clearance and host homeostasis [33–35]. Therefore, understanding cellular and molecular factors in response to the exposure of OMVs could be highly relevant for susceptibility to infection.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small non-coding RNA molecules that are involved in the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression [36,37]. These molecules are essential in different biological processes, such as development, proliferation, differentiation, cell death and disease [38]. In infected epithelial cells, downregulation of miRNAs increases the expression of cytokines, chemokines, adhesion factors and costimulatory molecules [39–42]. Little is known about the function of miRNAs in the human bronchial epithelial cells after OMV interaction.

2. Characterization of K. pneumoniae-Derived OMVs

In order to define the structural and functional characteristics of OMVs produced by K. pneumoniae, vesicles were purified from three different strains: K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae (clinical isolate) and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (clinical isolate). The strains were cultured to stationary phase and their OMVs were collected. To guarantee precise accuracy of the analyses, three independent purifications of the OMVs were performed for each strain. All vesicles were analysed in terms of diameter and size distribution, through DLS. DLS analysis showed that most OMVs of K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 presented a diameter of 273.3 ± 1.3 nm and were characterized by a slightly heterogeneous size distribution, confirmed by the polydispersity index of 0.329 ± 0.021. OMV vesicles from isolated clinical strains showed an increase in size and a greater heterogeneity of vesicular populations. The OMVs of MS K. pneumoniae predominately exhibited a diameter of 427.1 ± 0.9 nm and the vesicle population showed a high heterogeneity, demonstrated by a polydispersity index of 0.417 ± 0.017. Similar results were obtained for OMVs produced by KPC-producing K. pneumoniae. The majority of these vesicles presented with a diameter of 483.3 ± 1.7 nm and a polydispersity index of 0.333 ± 0.132, suggesting a heterogeneous population in size distribution (Table 2). All purified OMVs were quantified based on protein yield. Protein concentrations of 0.08 ± 0.06 mg/mL, 0.14 ± 0.03 mg/mL and 0.21 ± 0.01 mg/mL had been generated by K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae, respectively, for 600 mL of LB culture (Table 3).

Table 2. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis measurements of the Z-average size (Z-ave) and polydispersity index (PDI) of the outer membrane vesicles (OMVs).

|

Bacterial Strain |

Z-Ave (d.nm) |

PDI |

|

K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 |

273.3 ± 1.3 |

0.329 ± 0.021 |

|

MS K. pneumoniae |

427.1 ± 0.9 |

0.417 ± 0.017 |

|

KPC-producing K. pneumoniae |

483.3 ± 1.7 |

0.333 ± 0.132 |

Table 3. Protein concentration of OMVs purified from different strains of K. pneumoniae.

|

Bacterial Strain |

Protein Concentration[mg/mL] |

|

K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 |

0.08 ± 0.06 |

|

MS K. pneumoniae |

0.14 ± 0.03 |

|

KPC-producing K. pneumoniae |

0.21 ± 0.01 |

3. SDS-PAGE and LC-MS/MS Analysis of OMVs

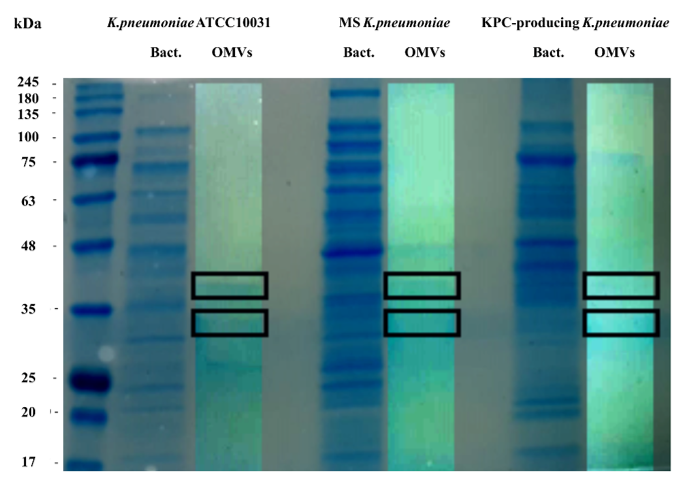

To evaluate the protein profile of the OMVs purified from K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae, 3.3 μg of protein was subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE (Figure 1). Two major bands, in the range of 30–40 KDa, were detected in the OMVs from K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae, with a clear difference from the bacterial lysate protein profile, confirming the absence of bacterial contaminants. The main protein bands were digested with trypsin and mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis was performed. Mass spectra analysis identified eight proteins common to all purified OMVs. The list of OMV proteins is reported in Table 4 in which identification name, function, molecular weight, and the total score values are indicated.

Figure 1. Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE (10%) protein profiles of K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae and relative OMVs. Molecular mass marker (MW) is expressed in kilodaltons (kDa). The rectangles indicate the bands subjected to trypsin digestion and MS and MS/MS analysis.

Table 4. Protein concentration of OMVs purified from different strains of K. pneumoniae.

|

Protein |

Function |

Theoretical MW (Da) |

Score |

|

Outer membrane protein A |

Action of colicins K and L |

37,152 |

1501 |

|

Outer membrane porin C |

Passive diffusion across the outer membrane |

39,639 |

1298 |

|

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Fragment) |

Enzyme in glycolysis |

32,457 |

680 |

|

Nucleoside-specific channel-forming protein |

Receptor for colicin K |

33,486 |

348 |

|

Malate dehydrogenase |

Enzyme in Krebs cycle |

32,549 |

180 |

|

Glucokinase |

Enzyme in glycolysis |

34,756 |

106 |

|

2-dehydro-3-deoxyphosphooctonate aldolase |

Enzyme in aminoacids synthesis |

31,033 |

97 |

|

Aminomethyltransferase |

enzyme in the glycine cleavage complex |

39,904 |

88 |

|

L-threonine 3-dehydrogenase |

Enzyme in L-threonine catabolism |

37,559 |

33 |

|

Elongation factor Ts |

Protein biosynthesis |

30,545 |

18 |

4. K. pneumoniae-Derived OMVs Affect miRNA Expression Profile in BEAS-2B Cells

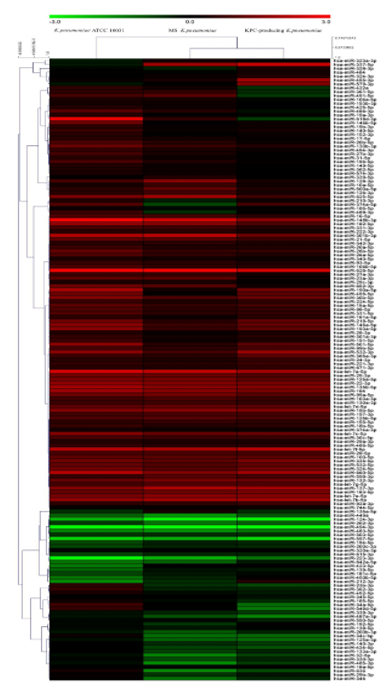

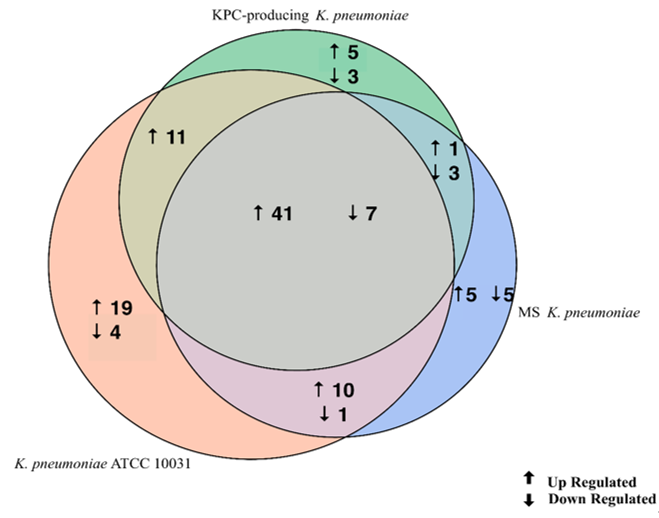

The evaluation of the expression profiles of miRNAs was carried out after treating BEAS 2B cells with OMVs purified from K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae. Using the TaqMan miRNA Array CARD, we screened the expression level of 384 miRNA sequences [45]. Raw microarray data were filtered and analysed. To give an illustrative and informative depiction, the results are shown via heatmap, using MeV software (MultiExperiment Viewer) (Figure 2). Transcripts with upregulated expression are indicated in red, while downregulated transcripts are indicated in green. In particular, the analysis revealed 115 miRNA sequences that were differentially regulated in treated samples compared to untreated controls (p < 0.05; cut-off > 1.5 or < −0.5). K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 derived OMVs induced the upregulation of 81 and downregulation of 13 miRNAs. In cells treated with MS K. pneumoniae derived OMVs, 57 miRNAs were upregulated and 16 were downregulated. Incubation with KPC-producing K. pneumoniae derived OMVs altered the expression of 71 miRNAs (58 upregulated and 13 downregulated). The differential analysis of miRNome profiling in response to each of the three treatments was compared and shown in the Venn diagram in Figure 3. The dysregulated miRNAs were common to all the three samples and the individually dysregulated miRNAs in each sample were used for gene ontology, biological function, and pathway analysis.

Figure 2. Heat map and hierarchical analysis of clusters. Heat map based on microarray results filtered and processed by bioinformatics analysis. Red indicates a greater expression than the control and green indicates a lower expression.

Figure 3. Venn diagram of differentially expressed miRNAs in three samples. The Venn diagram shows the different expressions of miRNAs after exposure of BEAS-2B cells to OMVs purified from three different strains of K. pneumoniae (ATCC 10031, MS and KPC-producing) compared to the control sample. The numbers in the intersecting circles represent the miRNA sequences commonly dysregulated in the different samples.

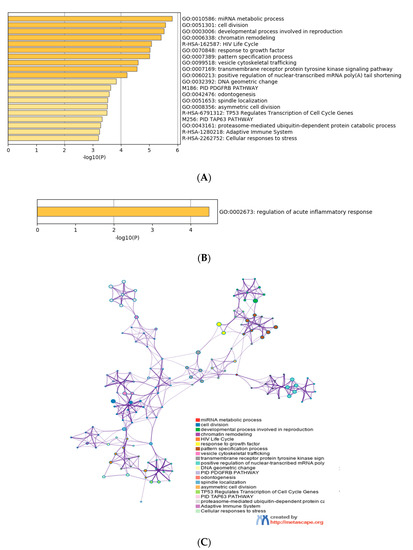

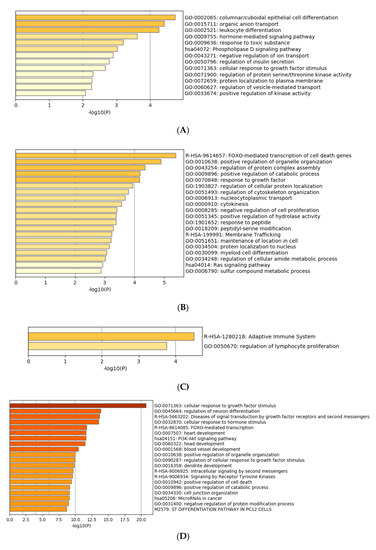

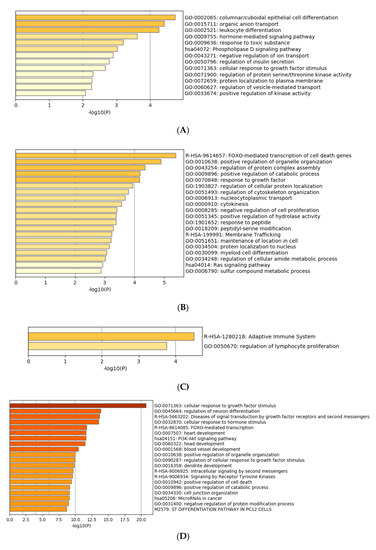

5. Functional Characterization of Target Genes

Gene ontology enrichment analysis was performed using Metascape software. The DIANA gene, Target Scan gene and MirTarBase gene software were exploited to filter predicted data. There were 41 miRNAs that were upregulated and seven that were downregulated in all samples following exposure to OMVs from three different K. pneumoniae strains. Predicted target genes of upregulated miRNA sequences in BEAS-2B cells were significantly associated with “miRNA metabolic processes” (GO: 0010586), “cell division” (GO: 0051301), “developmental processes involved in reproduction” (GO: 0003006), “chromatin remodelling” (GO: 0006338) and “response to growth factor” (GO: 0070848) (Figure 4A). Target genes of seven downregulated miRNA sequences were involved in “regulation of acute inflammatory response” (GO: 0002673) (Figure 4B). All identified biological processes are closely related (Figure 4C). Our analysis also assessed the differences in expression of miRNA induced by K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, MS K. pneumoniae and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae OMVs. After exposure with K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031, 19 and four miRNA sequences are upregulated and downregulated, respectively. Upregulated miRNA sequences were involved in “glandular epithelial cell development” (GO: 0002068), “DNA damage response, detection of DNA damage” (GO:0042769) and “positive regulation of apoptotic process” (GO: 0043065) (Figure 5A). The downregulated miRNAs were strongly associated with “cellular response to hormone stimulus” (GO: 0032870) (Figure 5B). The treatment with the MS strain upregulated and downregulated five different miRNA sequences in BEAS-2B cells. Five upregulated miRNA sequences were involved with the “adaptive immune system” (R-HSA-1280218) (Figure 5C) while the five downregulated miRNA sequences were related to the “cellular response to growth factor stimulus” (GO: 0071363), “regulation of neuron differentiation” (GO: 0045664) and “disease of signal transduction by growth factor receptors and second messengers “(R-HSA-5663202) (Figure 5D). The exposure to KPC-producing K. pneumoniae OMVs resulted in the upregulation and downregulation of five and three miRNA sequences, respectively. Upregulated sequences were involved in “FOXO-mediated transcription of cell death genes” (R-HSA-9614657), “positive regulation of organelle organization” (GO: 0010638) and “regulation of protein complex assembly” (GO: 0043254) (Figure 5E). Downregulated miRNA sequences were mainly associated with “columnar/cuboidal epithelial cell differentiation” (GO: 0002065) (Figure 5F).

Figure 4. Analysis of the functional enrichment of target genes. (A, B) The main enrichment analysis clusters detected by Metascape of genes associated with upregulated miRNA after treatment with OMVs; (C) interaction network of the clusters detected by Metascape. The nodes of the same colour belong to the same cluster. Terms with a similarity score > 0.3 are linked by an edge. The network is visualized with Cytoscape (v3.1.2) with a “force-directed” layout and edge bundled for clarity.

Figure 5. Gene prediction analysis. MiRNA sequences up and downregulated in the BEAS-2B sample exposed to OMVs of K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 (A,B), MS K. pneumoniae (C,D) and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (E,F).

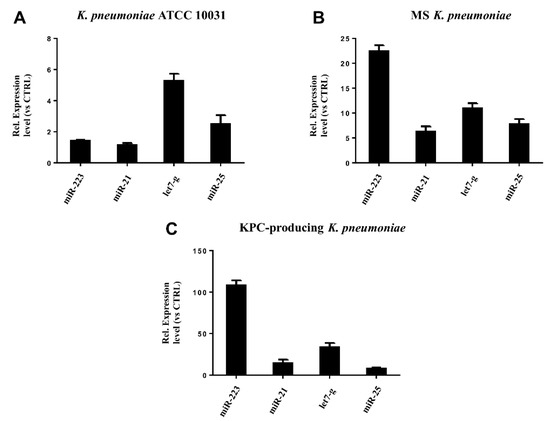

6. miRNAs Validation

RT-qPCR was used to confirm the gene expression results obtained from microarray analysis. Four miRNAs (hsa-miR-223, hsa-miR-21, hsa-miR-25, hsa-let-7g) were selected for validation. The expression of the analysed miRNAs showed a good compliance with microarray data (Figure 6). These findings suggest that the microarray data were reliable, supported by similar fold changes. The expression levels in the miRNAs hsa-miR-223, hsa-miR-21 and hsa-let-7g were significantly higher in the treatment with KPC-producing K. pneumoniae OMVs. In contrast, the OMVs from MS strain induced higher expression levels than OMVs from ATCC 10031 strain. For hsa-miR-25, there were no significant variations in expression between treatment with OMVs derived from KPC-producing K. pneumoniae and MS strain.

Figure 6. Validation of miRNA microarray data by real-time PCR. The expression levels of miR-21, miR-25, miR223, and let-7g were consistent with the miRNA microarray results after treatment with K. pneumoniae ATCC 10031 (A), MS K. pneumoniae (B) and KPC-producing K. pneumoniae (C).

References

- Caneiras, C.; Lito, L.; Melo-Cristino, J.; Duarte, A. Community- and Hospital-Acquired Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infections in Portugal: Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 138, doi:10.3390/microorganisms7050138.

- Lee, C.R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Jeon, J.H.; Kim, Y.B.; Cha, C.J.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Antimicrobial Resistance of Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: Epidemiology, Hypervirulence-Associated Determinants, and Resistance Mechanisms. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 483, doi:10.3389/fcimb.2017.00483.

- Podschun, R.; Ullmann, U. Klebsiella spp. as nosocomial pathogens: Epidemiology, taxonomy, typing methods, and pathogenicity factors. Microbiol. Rev. 1998, 11, 589–603.

- Bengoechea, J.A.; Sa Pessoa, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae infection biology: Living to counteract host defences. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2019, 43, 123–144, doi:10.1093/femsre/fuy043.

- Paczosa, M.K.; Mecsas, J. Klebsiella pneumoniae: Going on the Offense with a Strong Defense. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2016, 80, 629–661, doi:10.1128/MMBR.00078-15.

- Lin, J.E.; Valentino, M.; Marszalowicz, G.; Magee, M.S.; Li, P.; Snook, A.E.; Stoecker, B.A.; Chang, C.; Waldman, S.A. Bacterial heat-stable enterotoxins: Translation of pathogenic peptides into novel targeted diagnostics and therapeutics. Toxins 2010, 2, 2028–2054, doi:10.3390/toxins2082028.

- Wang, H.; Zhong, Z.; Luo, Y.; Cox, E.; Devriendt, B. Heat-Stable Enterotoxins of Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and Their Impact on Host Immunity. Toxins 2019, 11, 24, doi:10.3390/toxins11010024.

- Buonocore, C.; Tedesco, P.; Vitale, G.A.; Esposito, F.P.; Giugliano, R.; Monti, M.C.; D’Auria, M.V.; de Pascale, D. Characterization of a New Mixture of Mono-Rhamnolipids Produced by Pseudomonas gessardii Isolated from Edmonson Point (Antarctica). Drugs 2020, 18, 269, doi:10.3390/md18050269.

- Morrill, H.J.; Pogue, J.M.; Kaye, K.S.; LaPlante, K.L. Treatment Options for Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2015, 2, ofv050, doi:10.1093/ofid/ofv050.

- Nordmann, P.; Poirel, L. Epidemiology and Diagnostics of Carbapenem Resistance in Gram-negative Bacteria. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S521-S528, doi:10.1093/cid/ciz824.

- Qureshi, Z.A.; Syed, A.; Clarke, L.G.; Doi, Y.; Shields, R.K. Epidemiology and clinical outcomes of patients with carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteriuria. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3100–3104, doi:10.1128/AAC.02445-13.

- Geng, T.T.; Xu, X.; Huang, M. High-dose tigecycline for the treatment of nosocomial carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine 2018, 97, e9961, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000009961.

- Martora, F.; Pinto, F.; Folliero, V.; Cammarota, M.; Dell’Annunziata, F.; Squillaci, G.; Galdiero, M.; Morana, A.; Schiraldi, C.; Giovane, A.; et al. Isolation, characterization and analysis of pro-inflammatory potential of Klebsiella pneumoniae outer membrane vesicles. Pathog. 2019, 136, 103719, doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103719.

- Toyofuku, M.; Nomura, N.; Eberl, L. Types and origins of bacterial membrane vesicles. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 13–24, doi:10.1038/s41579-018-0112-2.

- Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Wang, Z. Outer membrane vesicles for vaccination and targeted drug delivery. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Nanomed. Nanobiotechnol. 2019, 11, e1523, doi:10.1002/wnan.1523.

- Kohl, P.; Zingl, F.G.; Eichmann, T.O.; Schild, S. Isolation of Outer Membrane Vesicles Including Their Quantitative and Qualitative Analyses. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1839, 117–134, doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-8685-9_11.

- Schwechheimer, C.; Kuehn, M.J. Outer-membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria: Biogenesis and functions. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 605–619, doi:10.1038/nrmicro3525.

- Zavan, L.; Bitto, N.J.; Johnston, E.L.; Greening, D.W.; Kaparakis-Liaskos, M. Helicobacter pylori Growth Stage Determines the Size, Protein Composition, and Preferential Cargo Packaging of Outer Membrane Vesicles. Proteomics 2019, 19, e1800209, doi:10.1002/pmic.201800209.

- Gerritzen, M.J.H.; Martens, D.E.; Wijffels, R.H.; van der Pol, L.; Stork, M. Bioengineering bacterial outer membrane vesicles as vaccine platform. Adv. 2017, 35, 565–574, doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2017.05.003.

- Lynch, J.B.; Schwartzman, J.A.; Bennett, B.D.; McAnulty, S.J.; Knop, M.; Nyholm, S.V.; Ruby, E.G. Ambient pH Alters the Protein Content of Outer Membrane Vesicles, Driving Host Development in a Beneficial Symbiosis. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00319-19, doi:10.1128/JB.00319-19.

- Ellis, T.N.; Kuehn, M.J. Virulence and immunomodulatory roles of bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 81–94, doi:10.1128/MMBR.00031-09.

- Guerrero-Mandujano, A.; Hernandez-Cortez, C.; Ibarra, J.A.; Castro-Escarpulli, G. The outer membrane vesicles: Secretion system type zero. Traffic 2017, 18, 425–432, doi:10.1111/tra.12488.

- Langlete, P.; Krabberod, A.K.; Winther-Larsen, H.C. Vesicles From Vibrio cholerae Contain AT-Rich DNA and Shorter mRNAs That Do Not Correlate With Their Protein Products. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2708, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02708.

- Bauwens, A.; Kunsmann, L.; Marejkova, M.; Zhang, W.; Karch, H.; Bielaszewska, M.; Mellmann, A. Intrahost milieu modulates production of outer membrane vesicles, vesicle-associated Shiga toxin 2a and cytotoxicity in Escherichia coli O157:H7 and O104:H4. Microbiol. Rep. 2017, 9, 626–634, doi:10.1111/1758-2229.12562.

- Jan, A.T. Outer Membrane Vesicles (OMVs) of Gram-negative Bacteria: A Perspective Update. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1053, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01053.

- Li, M.; Zhou, H.; Yang, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Bacterial outer membrane vesicles as a platform for biomedical applications: An update. Control. Release 2020, 323, 253–268, doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2020.04.031.

- Bomberger, J.M.; Maceachran, D.P.; Coutermarsh, B.A.; Ye, S.; O’Toole, G.A.; Stanton, B.A. Long-distance delivery of bacterial virulence factors by Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000382, doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000382.

- Cooke, A.C.; Nello, A.V.; Ernst, R.K.; Schertzer, J.W. Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm membrane vesicles supports multiple mechanisms of biogenesis. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0212275, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212275.

- Koeppen, K.; Barnaby, R.; Jackson, A.A.; Gerber, S.A.; Hogan, D.A.; Stanton, B.A. Tobramycin reduces key virulence determinants in the proteome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane vesicles. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211290, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0211290.

- Fiocca, R.; Necchi, V.; Sommi, P.; Ricci, V.; Telford, J.; Cover, T.L.; Solcia, E. Release of Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin by both a specific secretion pathway and budding of outer membrane vesicles. Uptake of released toxin and vesicles by gastric epithelium. Pathol. 1999, 188, 220–226, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199906)188:2<220::AID-PATH307>3.0.CO;2-C.

- Ronci, M.; Del Prete, S.; Puca, V.; Carradori, S.; Carginale, V.; Muraro, R.; Mincione, G.; Aceto, A.; Sisto, F.; Supuran, C.T.; et al. Identification and characterization of the alpha-CA in the outer membrane vesicles produced by Helicobacter pylori. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2019, 34, 189–195, doi:10.1080/14756366.2018.1539716.

- Cecil, J.D.; Sirisaengtaksin, N.; O’Brien-Simpson, N.M.; Krachler, A.M. Outer Membrane Vesicle-Host Cell Interactions. Spectr. 2019, 7, 201–214, doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.PSIB-0001-2018.

- Atkins, D.; Furuta, G.T. Mucosal immunology, eosinophilic esophagitis, and other intestinal inflammatory diseases. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2010, 125, S255-261, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.037.

- Chen, J.K.; Guo, M.K.; Bai, X.H.; Chen, L.Q.; Su, S.M.; Li, L.; Li, J.Q. Astragaloside IV ameliorates intermittent hypoxia-induced inflammatory dysfunction by suppressing MAPK/NF-kappaB signalling pathways in Beas-2B cells. Sleep Breath. 2020, 24, 1237–1245, doi:10.1007/s11325-019-01947-8.

- Clark, H.R.; Powell, A.B.; Simmons, K.A.; Ayubi, T.; Kale, S.D. Endocytic Markers Associated with the Internalization and Processing of Aspergillus fumigatus Conidia by BEAS-2B Cells. mSphere 2019, 4, doi:10.1128/mSphere.00663-18.

- Giudice, A.; D’Arena, G.; Crispo, A.; Tecce, M.F.; Nocerino, F.; Grimaldi, M.; Rotondo, E.; D’Ursi, A.M.; Scrima, M.; Galdiero, M.; et al. Role of Viral miRNAs and Epigenetic Modifications in Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Gastric Carcinogenesis. Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6021934, doi:10.1155/2016/6021934.

- Powell, C.D.; Quain, D.E.; Smart, K.A. The Impact of Ageing on CHITIN Scars in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. World J. 2001, 1, 145, doi:10.1100/tsw.2001.246.

- Mens, M.M.J.; Ghanbari, M. Cell Cycle Regulation of Stem Cells by MicroRNAs. Cell. Rev. Rep. 2018, 14, 309–322, doi:10.1007/s12015-018-9808-y.

- Jung, N.; Schenten, V.; Bueb, J.L.; Tolle, F.; Brechard, S. miRNAs Regulate Cytokine Secretion Induced by Phosphorylated S100A8/A9 in Neutrophils. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5699, doi:10.3390/ijms20225699.

- McCoy, C.E. The role of miRNAs in cytokine signaling. Biosci. 2011, 16, 2161–2171, doi:10.2741/3845.

- Nejad, C.; Stunden, H.J.; Gantier, M.P. A guide to miRNAs in inflammation and innate immune responses. FEBS J. 2018, 285, 3695–3716, doi:10.1111/febs.14482.

- Salvi, V.; Gianello, V.; Tiberio, L.; Sozzani, S.; Bosisio, D. Cytokine Targeting by miRNAs in Autoimmune Diseases. Immunol. 2019, 10, 15, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00015.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms8121985