This review critically examines the implementation of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) in science education, providing an integrative overview of research, methodologies, and disciplinary applications. The first section explores UDL across educational stages—from early childhood to higher education—highlighting how age-specific adaptations, such as play-based and outdoor learning in early years or language- and problem-focused strategies in secondary education, enhance engagement and equity. The second section analyses science-specific pedagogies, including inquiry-based science education, the 5E model (Engage, Explore, Explain, Elaborate, Evaluate), STEM/STEAM approaches, and gamification, demonstrating how their alignment with UDL principles fosters motivation, creativity, and metacognitive development. The third section addresses the application of UDL across scientific disciplines—biology, physics, chemistry, geosciences, environmental education, and the Nature of Science—illustrating discipline-oriented adaptations and inclusive practices. Finally, a section on multiple scenarios of diversity synthesizes UDL responses to physical, sensory, and learning difficulties, neurodivergence, giftedness, and socio-emotional barriers. The review concludes by calling for enhanced teacher preparation and providing key ideas for professionals who want to implement UDL in science contexts.

Understanding Universal Design for Learning: A Comprehensive Definition

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a theoretical and practical framework developed in 1984 by the Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST), aiming to enhance learning for all students [

1]. Interestingly, the term “universal design” did not originate in the field of education but in architecture. Architect Ron Mace and his colleagues coined it to describe products and environments designed to be usable by all people to the greatest extent possible (e.g., curb-cut sidewalks) [

2]. Building on this foundational idea, CAST has progressively refined and expanded the UDL model. Over time, the framework has evolved from its early focus on reducing cognitive and physical barriers [

1,

3] to a broader commitment to achieving social justice through the elimination of prejudice and systemic exclusion [

4]. A concise overview of UDL’s historical development is provided by Schreffler et al. (2019) [

5].

The central premise of UDL is that many barriers to learning are not inherent to students’ abilities but often arise from their interaction with rigid educational materials and methods [

2]. This perspective reverses the traditional viewpoint arguing that it is curricula that require modification—not the learners themselves [

6]. The framework adopts an interdisciplinary foundation, drawing from neuroscience, pedagogy, and psychology [

7]. Its ultimate goal is to develop expert learners who are, each in their own way, resourceful, knowledgeable, strategic, goal-directed, purposeful, and motivated [

1].

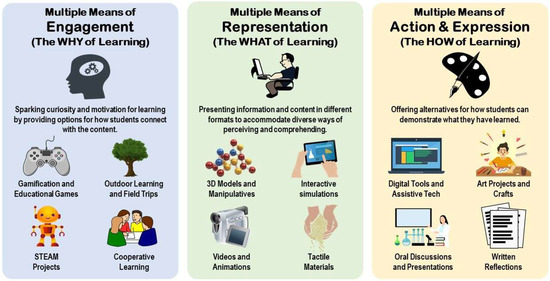

The UDL model is structured around three core principles, which are elaborated into nine guidelines and thirty-six checkpoints [

4]. The first principle, providing multiple means of engagement (the why of learning), focuses on sustaining interest, offering appropriate challenges, and enhancing motivation. This is accomplished by employing approaches that enhance learners’ autonomy and decision-making, encourage cooperative engagement and a sense of community, guarantee the meaningfulness and real-world applicability of tasks, and support the development of reflective thinking and emotional self-management. The second principle, providing multiple means of representation (the what of learning), addresses the diverse ways that students perceive and comprehend information. It entails delivering material through diverse formats, elucidating key terms and symbols, providing alternatives for tailoring how information is presented, and drawing on learners’ existing knowledge to facilitate the acquisition of new concepts. The third principle, providing multiple means of action and expression (the how of learning), acknowledges that students differ in how they navigate learning environments and demonstrate understanding. These strategies encompass enhancing the availability of assistive tools, employing a range of media for communication and content creation, supplying diverse options for how learners can respond, and providing structured support for setting goals, organizing tasks, and tracking progress.

Several parallel frameworks have been developed, inspired by UDL. In 2001, researchers at the University of Connecticut expanded UDL principles to design the Universal Design for Instruction (UDI), which articulates nine principles aimed at enhancing accessibility in higher education [

8]. UDI emphasizes flexibility, tolerance for error, adequate space, and an inclusive climate. Another derivative model, the Universal Design of Assessment, draws from UDL to promote inclusive evaluation practices [

9], seeking to measure students’ actual competencies rather than limitations arising from format, language, or testing conditions. Although this paper focuses primarily on UDL, other pedagogical approaches also address classroom diversity, including Culturally Relevant Pedagogy, Culturally Responsive Teaching, and Differentiated Instruction [

10].

The implementation of UDL is justified by the need to remove barriers within learning environments to ensure equitable access to education for all students [

11]. Moreover, Sustainable Development Goals 4 and 10—Quality Education and Reducing Inequalities—represent core priorities in the United Nations Agenda, urging global efforts toward inclusive education [

12]. Today, UDL has been widely adopted as an approach for creating equitable and responsive learning environments [

13]. While several authors have documented its benefits [

14], others question its effectiveness, noting a lack of sufficient empirical evidence to fully substantiate its outcomes [

15]. Most studies focus on students’ perceptions [

16] and tend to emphasize the principle of representation over the rest of the principles or measurable learning outcomes [

17,

18]. Furthermore, critical questions remain unresolved, such as the adequate “dosage” of UDL interventions [

9], the potential role of technology [

19], and how to systematically assess them [

20].

Examining the Relevance of UDL in Science Education

Scientific literacy constitutes a fundamental competency in modern society, especially in light of the growing range of science- and technology-related challenges [

21]. It comprises the knowledge and comprehension of scientific ideas and methods needed for well-informed personal choices, meaningful engagement in civic and cultural life, and effective contribution to economic activity [

22]. Although science learning presents challenges for all students, these challenges are often magnified for learners who struggle with reading and writing or who exhibit low motivation toward science learning [

23]. Science subjects frequently involve abstract and complex content, and students often hold misconceptions that interfere with conceptual understanding [

24]. Many learners also encounter difficulties using scientific terminology to describe or explain concepts, as limited science vocabulary has been identified as a persistent barrier in the literature [

25]. Lemke (1990) [

26] argues that learners are rarely taught how to “talk science,” a skill required to discuss, explore, investigate, and express scientific ideas both orally and in writing. Furthermore, experiments and laboratory procedures can be challenging because they require students to integrate conceptual reasoning with methodological processes [

27]. In addition to these general obstacles, students with learning or physical difficulties face extra barriers and often perform below their peers in science courses [

28].

A significant precursor study that provided insights and best practices for improving accessibility in science education was the book

Creating a Culture of Accessibility in the Sciences [

29]. Since then, several studies have demonstrated that UDL-based science lessons can enhance accessibility, self-regulation, and classroom attention [

5]. Moore et al. (2020) [

30] further recommended that team-based learning, when aligned with UDL guidelines, can be particularly beneficial for students. In

Figure 1, several examples of science-class methodologies are aligned with the UDL principles.

Figure 1. Examples of science-class methodologies adjusted to the three UDL principles.

Despite these contributions, there remains a shortage of studies directly linking inclusion and science education [

31], and, to our knowledge, comprehensive reviews addressing this relationship under different perspectives remain scarce.

In response to this gap, the present narrative review aims to synthesize the most relevant findings connecting UDL with science education. It analyzes the impact of UDL implementation across four dimensions: educational stages, science-specific methodologies, disciplinary applications, and diverse inclusion scenarios. This integrative and multimodal approach seeks to identify best practices for applying UDL in science classrooms while also highlighting existing limitations and directions for future research. The studies included in this review were selected according to the following criteria: empirical or theoretical works published in peer-reviewed journals or scholarly books between 1990 and 2025; explicit relevance to the implementation of UDL within science education across the four focal dimensions; and availability in English. The literature was identified through targeted keyword searches in major academic databases (Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar), complemented by backward citation analysis. Throughout this review, the term “disability”, which is quite common in the literature, has been purposely substituted by “difficulty” or “access limitation”, since the authors align with the idea that it is the curricula that require modification, not the learners themselves, and difficulties appear when learning methodologies are not well adjusted to them.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/encyclopedia6010024