Clostridium botulinum is a Gram-positive, spore-forming, obligate anaerobic bacterium widely distributed in soils, sediments, and aquatic environments. It is best known as the causative agent of botulism, a severe neuroparalytic disease caused by the production of botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), among the most potent biological toxins known.

- Clostridium botulinum

- botulism

- BoNTs

1. Taxonomy and Classification

Clostridium botulinum belongs to the phylum Firmicutes, class Clostridia, order Clostridiales, and family Clostridiaceae. Taxonomically, the species is heterogeneous, encompassing four distinct physiological groups (I–IV), which differ in their genetic characteristics, proteolytic activity, growth temperature ranges, and ecological niches [1][2].

-

Group I (Proteolytic C. botulinum): Produces toxin types A, B, and F. Associated with human botulism, particularly foodborne outbreaks. These strains are proteolytic, capable of degrading complex proteins, and grow optimally at mesophilic temperatures.

-

Group II (Nonproteolytic C. botulinum): Produces toxin types B, E, and F. Associated with botulism linked to fish and other aquatic sources. They are psychrotrophic and capable of growth at refrigeration temperatures, posing a risk in chilled foods.

-

Group III: Produces toxin types C and D. Primarily associated with animal botulism in birds and mammals, rarely affecting humans.

-

Group IV (C. argentinense): Produces toxin type G. Rarely linked to disease in humans or animals, but retains genetic capacity for toxinogenesis.

Recent phylogenomic analyses have shown that these groups are genetically diverse and could represent separate species; however, they remain collectively designated as C. botulinum for historical and clinical reasons [3].

2. Morphology and Physiology

Clostridium botulinum is a rod-shaped, motile bacterium that forms oval, subterminal spores, giving the cells a distinctive bulging appearance. It is strictly anaerobic, although some strains show aerotolerance.

-

Size: Vegetative cells are typically 4–6 µm in length.

-

Spore formation: The spores are highly resistant to heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemical disinfectants. This resilience underlies the persistence of the organism in natural environments and food systems.

-

Metabolism: Depending on the group, strains may be proteolytic or saccharolytic. Proteolytic strains hydrolyze proteins, producing foul-smelling metabolites such as butyric acid.

-

Growth conditions:

-

Group I strains: Mesophilic, optimal growth at 35–40 °C.

-

Group II strains: Psychrotrophic, capable of growth at 3–5 °C.

-

pH tolerance: Growth inhibited below pH 4.6.

-

Salt tolerance: Growth inhibited at NaCl concentrations above 10%.

-

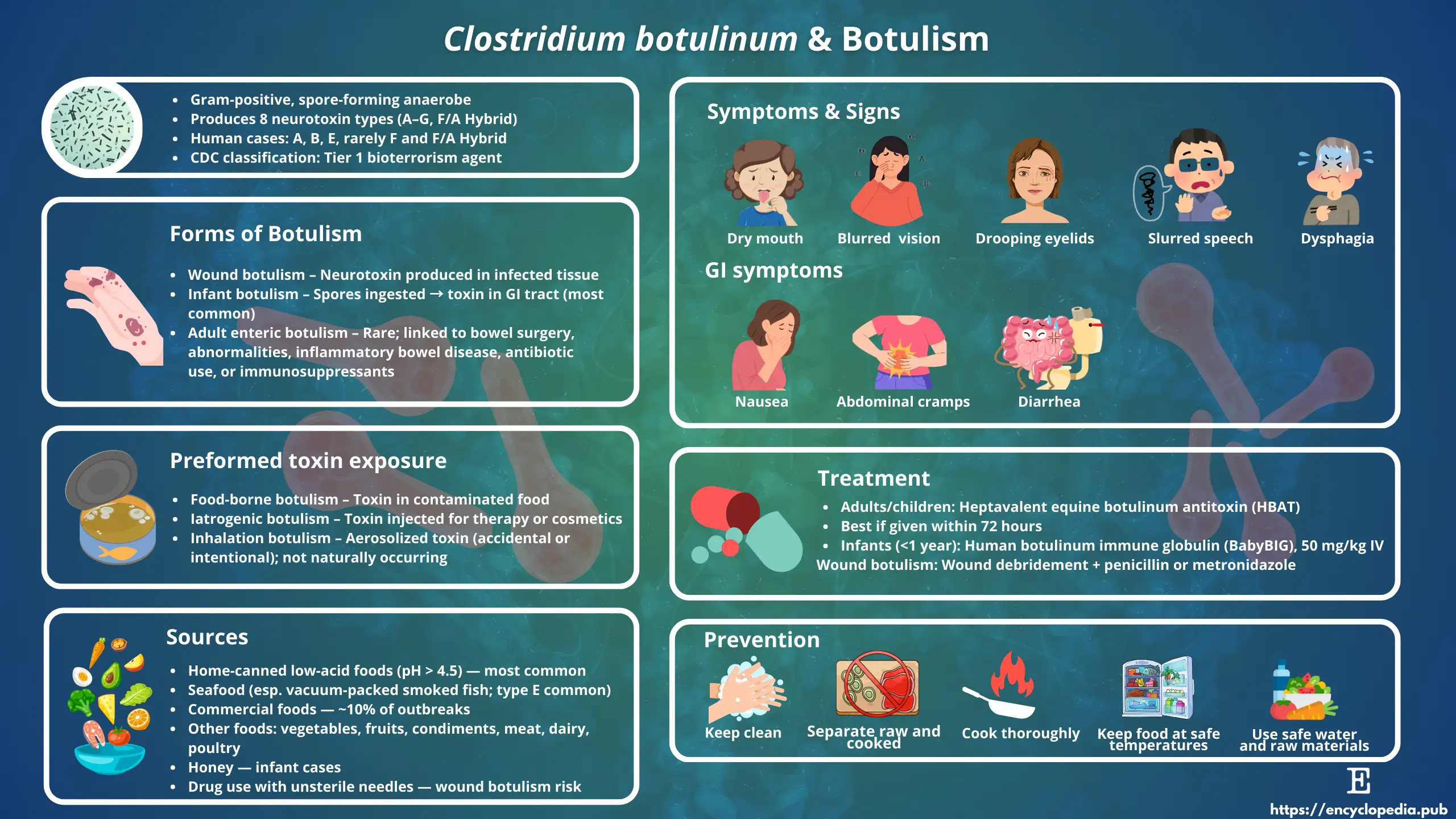

Source: Encyclopedia Scientific Infographic (https://encyclopedia.pub/image/3368)

3. Ecology and Distribution

Clostridium botulinum is ubiquitous in the environment. Its spores have been isolated from soils, sediments of lakes and oceans, and the intestinal tracts of mammals, birds, and fish [4].

-

Terrestrial reservoirs: Group I strains are predominantly terrestrial, associated with soil and decaying vegetation.

-

Aquatic reservoirs: Group II strains are frequently isolated from marine and freshwater sediments, making them significant in fish-related botulism cases.

-

Animal reservoirs: Group III strains colonize the gastrointestinal tracts of birds, cattle, and other animals, often causing epizootics.

Environmental persistence is primarily attributed to the spore form, which can survive for decades under adverse conditions.

4. Botulinum Neurotoxins (BoNTs)

The clinical significance of C. botulinum arises from its ability to produce botulinum neurotoxins (BoNTs), a family of metalloproteases targeting neuronal proteins.

4.1. Toxin Types and Subtypes

-

Serotypes A–G: Seven confirmed toxin serotypes have been identified. A proposed type H has been reclassified as a hybrid toxin related to type F [5].

-

Subtypes: Each serotype includes multiple subtypes with genetic and functional variations. For example, BoNT/A has at least eight subtypes (A1–A8).

4.2. Mechanism of Action

BoNTs block acetylcholine release at neuromuscular junctions:

-

Binding: The heavy chain of the toxin binds to specific receptors on cholinergic nerve endings.

-

Endocytosis: The toxin-receptor complex undergoes endocytosis.

-

Translocation: Acidification triggers translocation of the light chain into the cytosol.

-

Proteolysis: The light chain, a zinc-dependent endopeptidase, cleaves SNARE proteins (synaptobrevin, SNAP-25, syntaxin), preventing synaptic vesicle fusion.

-

Clinical outcome: Blockade of acetylcholine release causes flaccid paralysis.

4.3. Relative Potency

BoNTs are among the most potent toxins known. The estimated human lethal dose is ~1 ng/kg body weight for BoNT/A, making it a major concern for food safety and bioterrorism [6].

5. Clinical Forms of Botulism

Human botulism manifests in several forms, all linked to ingestion, colonization, or exposure to BoNTs.

5.1. Foodborne Botulism

-

Caused by ingestion of preformed toxin in improperly preserved or canned foods.

-

Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, followed by descending flaccid paralysis, cranial nerve palsies, and respiratory failure.

-

Outbreaks often linked to home-canned vegetables, fermented fish, and cured meats.

5.2. Infant Botulism

-

Occurs in infants under 12 months due to colonization of the immature intestine by C. botulinum spores, which germinate and produce toxin in situ.

-

Honey is a known risk factor.

-

Symptoms: Constipation, poor feeding, hypotonia (“floppy baby syndrome”).

5.3. Wound Botulism

-

Arises when spores contaminate deep wounds, particularly in injection drug users.

-

Clinical presentation is similar to foodborne botulism but without gastrointestinal symptoms.

5.4. Adult Intestinal Toxemia

-

Rare form in adults with altered gut microbiota or underlying conditions.

5.5. Iatrogenic Botulism

-

Caused by overdose or diffusion of therapeutic BoNT during medical or cosmetic use.

6. Diagnosis

Diagnosis requires rapid recognition due to the severity of the disease.

-

Clinical evaluation: Symptom progression (cranial nerve involvement, symmetrical paralysis, absence of fever).

-

Laboratory methods:

-

Mouse bioassay: Historical gold standard for toxin detection.

-

ELISA, endopeptidase activity assays, and PCR-based assays: Modern, sensitive alternatives.

-

-

Specimen sources: Serum, stool, gastric aspirates, wound exudates, and implicated foods.

7. Treatment and Management

Prompt intervention is critical.

-

Antitoxin therapy: Equine-derived heptavalent botulinum antitoxin (HBAT) neutralizes circulating toxin but does not reverse established paralysis. For infants, human-derived botulism immune globulin (BabyBIG®) is recommended.

-

Supportive care: Mechanical ventilation may be required for weeks to months until neuromuscular recovery occurs.

-

Wound care: Surgical debridement and antibiotics (e.g., penicillin, metronidazole).

8. Prevention and Control

-

Food safety:

-

Proper sterilization of canned foods (121 °C for 3 min to inactivate spores).

-

Maintaining food pH <4.6.

-

Adequate refrigeration and avoidance of vacuum packaging of raw fish products.

-

-

Public health measures: Surveillance, outbreak investigation, and public education on safe canning practices.

-

Environmental control in animals: Vaccination against types C and D used in livestock.

9. Biotechnological and Medical Applications

Paradoxically, BoNTs have been repurposed as therapeutic agents in controlled doses.

-

Medical uses:

-

Treatment of strabismus, blepharospasm, cervical dystonia, chronic migraine, and hyperhidrosis.

-

Investigational use in neuropathic pain, depression, and gastrointestinal disorders.

-

-

Cosmetic use:

-

Commercially known as “Botox®,” widely used to reduce facial wrinkles.

-

The therapeutic application highlights the dual nature of BoNTs as both deadly toxins and beneficial drugs.

10. Public Health and Biodefense Significance

Due to their extreme potency, BoNTs are classified as Category A bioterrorism agents by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). A small quantity dispersed in food, water, or aerosols could cause mass casualties. Ongoing research focuses on developing improved antitoxins, vaccines, and detection systems to mitigate these threats [7].

11. Research Directions

-

Genomics: Comparative genomics has revealed extensive horizontal gene transfer, explaining the diversity of toxin gene clusters.

-

Microbiome interactions: Studies explore how gut microbiota composition influences susceptibility to colonization and toxin production.

-

Novel therapeutics: Engineering of BoNT derivatives for targeted drug delivery and reduced side effects.

12. Conclusion

Clostridium botulinum is an ecologically diverse bacterium with profound medical and public health significance. While notorious as the source of botulism, it has also been harnessed as a therapeutic tool, exemplifying the complex interplay between microbial toxins and human health. Continued vigilance in food safety, outbreak management, and bioterrorism preparedness is essential, alongside ongoing research into novel applications and improved countermeasures.

References

- Peck, M. W. Biology and genomic analysis of Clostridium botulinum. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2017, 71, 1–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.03.001.

- Smith, T. J.; Hill, K. K.; Raphael, B. H. Historical and current perspectives on Clostridium botulinum diversity. Res. Microbiol. 2015, 166(4), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2014.09.007.

- Zhang, Z.; Hintsa, H.; et al. Whole-genome phylogeny of Clostridium botulinum groups I–IV reveals species-level divergence. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 580. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.00580.

- Carter, A. T.; Peck, M. W. Genomes, neurotoxins and biology of Clostridium botulinum group I and group II. Res. Microbiol. 2015, 166(4), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resmic.2014.12.007.

- Maslanka, S. E.; et al. A novel botulinum neurotoxin, previously reported as serotype H, has a hybrid F/A sequence. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 213(3), 379–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiv327.

- Gill, D. M. Bacterial toxins: a table of lethal amounts. Microbiol. Rev. 1982, 46(1), 86–94. PMID: 6806598.

- Arnon, S. S.; et al. Botulinum toxin as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 2001, 285(8), 1059–1070. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.8.1059.