The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is a unique monotreme endemic to eastern Australia and Tasmania. As one of only five extant monotreme species, the platypus presents a rare blend of mammalian, reptilian, and avian features, including egg-laying, electroreception, venom production, and milk secretion without nipples.

- platypus

- Ornithorhynchus anatinus

- monotreme endemic

- Ornithorhynchidae

1. Introduction

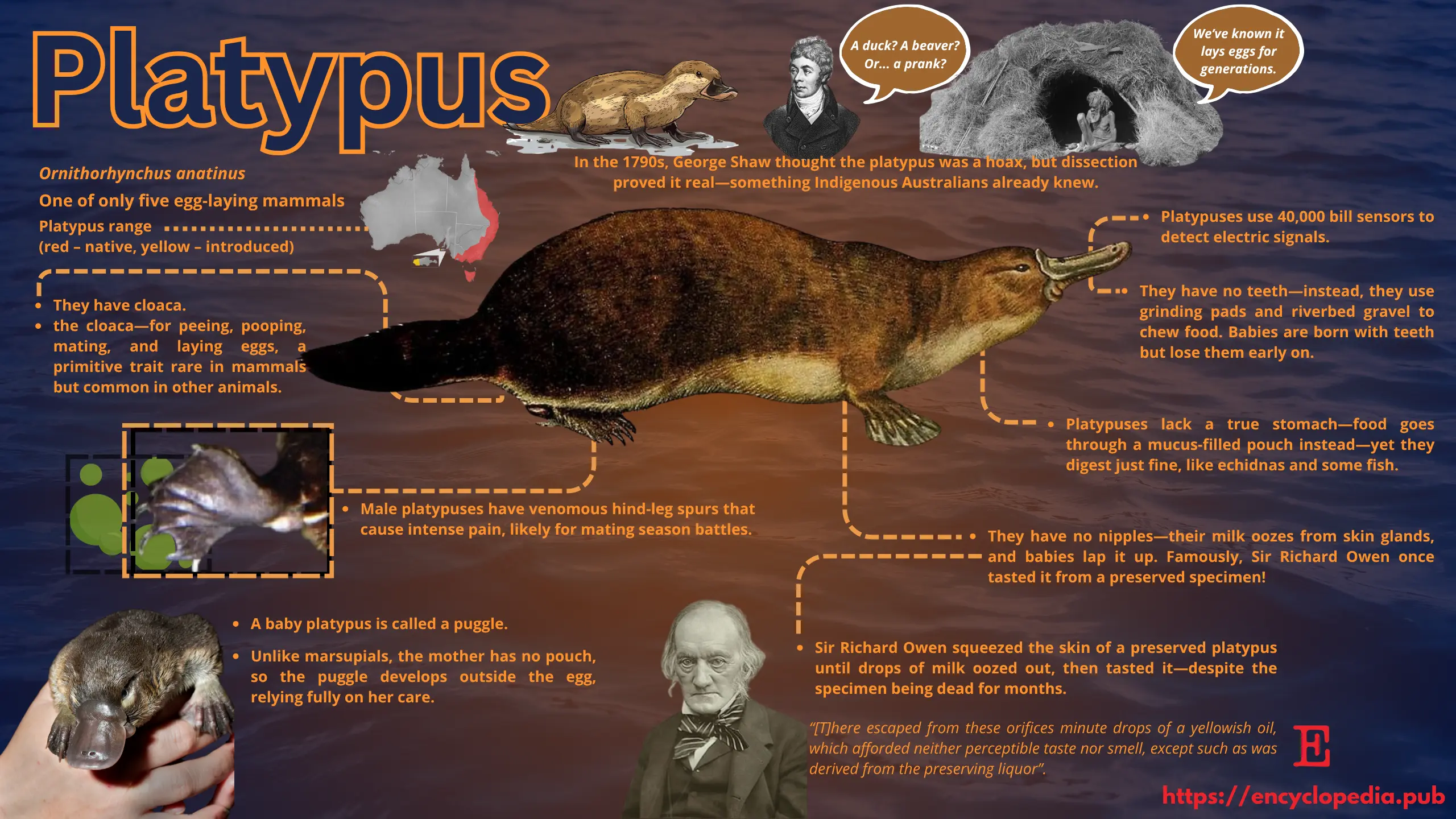

The platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) is a unique and evolutionarily significant monotreme endemic to eastern Australia and Tasmania. Distinguished by its unusual blend of mammalian, reptilian, and avian characteristics, the platypus has intrigued scientists and naturalists since its first documentation by Europeans in the late 18th century. As one of only five extant monotreme species, and the sole representative of its genus and family (Ornithorhynchidae), the platypus occupies a critical phylogenetic position within Mammalia, providing essential insights into early mammalian evolution.

The morphological peculiarities of the platypus—including its duck-like bill, webbed feet, electroreception capabilities, venom-producing spur in males, and oviparous reproductive strategy—challenge conventional definitions of mammalian biology. These features have rendered the species an emblem of evolutionary divergence and adaptive specialization. The sequencing of the platypus genome has further underscored its evolutionary novelty, revealing a mosaic of reptilian, mammalian, and avian genes and supporting theories of ancient lineage divergence within Monotremata.

Source: Encyclopedia Scientific Infographics (https://encyclopedia.pub/image/3653)

Ecologically, the platypus plays a crucial role in freshwater ecosystems, where it acts as a semi-aquatic predator of aquatic invertebrates. Despite its evolutionary and ecological importance, the species faces growing conservation concerns due to habitat destruction, climate change, waterway degradation, and localized anthropogenic pressures. Recent studies have highlighted alarming declines in population numbers across parts of its range, prompting discussions on its conservation status and the necessity of legal protection at both national and international levels.

2. Taxonomy and Evolutionary Position

-

Kingdom: Animalia

-

Phylum: Chordata

-

Class: Mammalia

-

Order: Monotremata

-

Family: Ornithorhynchidae

-

Genus: Ornithorhynchus

-

Species: O. anatinus

The platypus is the only extant representative of the family Ornithorhynchidae. Along with echidnas (family Tachyglossidae), it belongs to the order Monotremata—egg-laying mammals that diverged early from the therian mammalian lineage. Molecular phylogenetics suggests that monotremes split from the rest of Mammalia approximately 250 million years ago, during the Triassic period, with the platypus lineage emerging around 166 million years ago [1]. Genomic analyses indicate a mixture of reptilian and mammalian features, including genes for yolk proteins, venom production, and electroreception [2].

3. Morphological Adaptations

3.1 General Morphology

Adult platypuses typically measure 43–50 cm in length and weigh 0.7–2.4 kg, with males generally larger than females. Their body is streamlined and covered in dense, waterproof fur. The most striking features include:

-

A flattened, duck-like bill containing electroreceptors

-

Webbed feet for aquatic propulsion

-

A broad, flat tail used for fat storage and steering

The skeletal structure retains several primitive features, including a sprawling gait and epipubic bones, characteristics shared with extinct therapsids [3].

3.2 Electroreception

The bill of the platypus contains approximately 40,000 electroreceptors, enabling it to detect minute electrical signals generated by the muscular contractions of prey [4]. This is one of the most sensitive electroreceptive systems known among mammals and facilitates foraging in turbid aquatic environments, where visual and olfactory cues are limited.

4. Physiology

4.1 Thermoregulation

Although monotremes have lower basal metabolic rates than eutherian mammals, the platypus maintains a relatively stable body temperature (~32°C), an adaptation to its semi-aquatic lifestyle [5].

4.2 Venom System

Male platypuses possess a keratinous spur on each hind limb connected to a venom gland. The venom, primarily used during the breeding season in male-male combat, contains defensin-like proteins (DLPs) and causes intense pain and swelling in humans [6].

4.3 Reproduction and Lactation

The platypus exhibits oviparity, laying one to three leathery-shelled eggs per breeding season. Females incubate eggs in a nesting burrow for about 10 days before hatching. Remarkably, the platypus lacks teats; instead, milk is secreted through openings in the skin and absorbed by the young through mammary patches [7]. This provides critical insight into the evolution of lactation in mammals.

5. Habitat and Distribution

The platypus inhabits freshwater streams, rivers, and lakes in eastern Australia and Tasmania, from the tropical rainforests of Queensland to the alpine regions of Victoria. Optimal habitats include stable water bodies with vegetated banks and abundant invertebrate prey. The species is largely solitary and territorial, particularly among males [8].

6. Diet and Foraging Behavior

The platypus is a carnivorous bottom-feeder. It primarily consumes aquatic invertebrates, such as insect larvae, worms, and freshwater crustaceans. Foraging usually occurs at night or during crepuscular hours. While diving, the animal closes its eyes, ears, and nostrils and relies entirely on tactile and electrical stimuli. It can perform repeated dives lasting up to 30 seconds and spends about 30–60% of its foraging time submerged [9].

7. Behavior and Life History

Platypuses are nocturnal and crepuscular, inhabiting burrows excavated into stream banks. The breeding season typically occurs between June and October. After mating, females construct elaborate nesting burrows with vegetative lining and seal the entrance with soil plugs. Juveniles remain in the burrow for about four months and emerge fully furred and weaned.

Lifespan in the wild averages 10–12 years, although individuals in captivity have lived over 20 years.

8. Conservation Status and Threats

8.1 IUCN Red List Status

The platypus is currently listed as “Near Threatened” by the IUCN [10], with population declines attributed to habitat degradation, drought, climate change, and pollution. Although once widespread, recent modeling suggests significant range contractions in New South Wales and Victoria due to extended dry periods and altered hydrological regimes.

8.2 Key Threats

-

Habitat fragmentation: Urban expansion and agriculture have led to the destruction of riparian zones and reduced connectivity between populations.

-

Climate change: Reduced rainfall and higher temperatures increase the frequency of drying waterways.

-

Pollution: Pesticides and heavy metals accumulate in aquatic prey and affect reproductive health.

-

Entanglement and bycatch: Platypuses are vulnerable to illegal netting and litter.

Conservation efforts include monitoring, riparian restoration, and legislative protections under state wildlife acts.

9. Scientific Significance

The platypus genome has offered critical insights into vertebrate evolution, particularly the transition from reptiles to mammals. It contains a mixture of mammalian (e.g., lactation and hair genes), avian (e.g., egg proteins), and reptilian features (Warren et al., 2008). Research into its venom, electroreception, and reproductive biology has provided new avenues for evolutionary biology, neuroscience, and pharmacology.

10. Cultural and Historical Perspectives

Since its discovery by Europeans in the late 18th century, the platypus has fascinated scientists and laypeople alike. Initial skepticism led some naturalists to believe it was a hoax. In Aboriginal cultures, the platypus holds symbolic importance, often featured in Dreamtime stories that explain its composite anatomy.

11. Conclusion

The platypus exemplifies evolutionary innovation, blending traits from across the animal kingdom. Its specialized morphology, unique reproductive strategy, and ecological sensitivity underscore the need for dedicated conservation action. As a living fossil, it continues to be a vital subject in comparative anatomy and evolutionary genomics, offering a rare window into early mammalian evolution.

References

- Phillips, M. J., Bennett, T. H., & Lee, M. S. Y. (2009). Molecules, morphology, and ecology indicate a recent, amphibious ancestry for echidnas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106(40), 17089–17094. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0904649106

- Warren, W. C., Hillier, L. W., Marshall Graves, J. A., et al. (2008). Genome analysis of the platypus reveals unique signatures of evolution. Nature, 453(7192), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06936.

- Musser, A. M. (1998). Monotreme evolution. In M. Augee (Ed.), Monotremes and Marsupials: Evolution and Ecology (pp. 12–33). UNSW Press.

- Pettigrew, J. D., Manger, P. R., & Fine, M. L. (1998). The sensory world of the platypus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 353(1372), 1199–1210. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1998.0270

- Grant, T. R., & Temple-Smith, P. D. (2003). Conservation of the platypus, Ornithorhynchus anatinus: Threats and challenges. Aquatic Ecosystem Health & Management, 6(1), 5–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/14634980301470.

- Whittington, C. M., Papenfuss, A. T., Bansal, P., et al. (2010). Defensins and the convergent evolution of platypus and reptile venom genes. Genome Research, 20(8), 986–993. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.101956.109

- Griffiths, M. (1978). The Biology of the Monotremes. Academic Press.

- Serena, M., & Williams, G. A. (2010). Movements and distribution of platypuses (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) in urban waterways. Wildlife Research, 37(7), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1071/WR10041.

- Bethge, P., Munks, S. A., Otley, H. M., & Nicol, S. C. (2003). Diving behaviour, dive cycles and aerobic dive limit in the platypus, Ornithorhynchus anatinus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology, 136(4), 799–809. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1095-6433(03)00250-5.

- Bino, G., Grant, T. R., Kingsford, R. T. (2020). A review of the status of the platypus in Australia. Biological Conservation, 248, 108559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108559.